On Christian Clothing

An Essay on History and the Contemporary Situation

By Valeriy Selishchev

Illustrations by Anastasia Rumyantseva

Repent, ye people, repent, pray to God with tears. And with heartfelt sobbing altogether. For the Antichrist sits upon the throne— This is the cunning seven-headed serpent. He has spewed forth his bitter fury. Throughout all the earth, throughout the universe, princes and boyars grew afraid. They fulfilled all his bitter will, eating meat on Wednesdays and Fridays. They clothed themselves in Latin attire, preparing themselves for the pit of perdition.

An old spiritual verse

To every person who sincerely desires to lead a Christian way of life and to observe the laws and customs of piety, it becomes clear that in such a matter there are no trifles or superficial, external things. The Lord tells us in the Holy Gospel that if we are faithful in little things, He will set us over much. One such thing must be considered our attitude toward Christian clothing and outward appearance.

In the Christian worldview, it is not customary to divide the confession of faith into external (non-obligatory) and internal (sacred) actions and rules. For by the incarnation of the Savior Christ, we are called in everything and by everything to preach the Truth about the indivisible and unconfused union in Christ of two natures—the Divine and the Human, the visible and the invisible. The Lord became incarnate in human form and, like our forefather Adam of old, clothed Himself in the garments of our nature. And earlier, the Lord granted leather garments to the first humans because it was unseemly for the fallen foreparents to remain naked. If before the Fall, forefather Adam and our foremother Eve knew no sin and, consequently, no shame for it: “And they were both naked, Adam and his wife, and were not ashamed”1Bible. First Book of Moses. Genesis, chapter 3., then afterward a covering for the body became necessary for them. “And the Lord God made garments of skin for Adam and his wife, and clothed them”2Ibid.. And our Christian clothing must correspond to the calling and purpose of man as a child of God.

From ancient Christians we can hear this instruction: “The Lord in that fearful hour will ask us: How will I know that you are Mine (that is, true Christians)? By deeds? But we often do not perform good deeds. By thoughts? But we have vain thoughts and worldly ideas. By clothing, at least? But even our outward appearance is not Christian!

So how will we answer God?

Paraphrasing a famous Russian writer, one can say: In a Christian, everything should be Christian: thoughts, deeds, and clothing…

And this is entirely just. For the Church Fathers and even ecumenical councils have left us instructions about clothing befitting Christians.

“Everywhere Holy Scripture commands us to dress in ordinary Christian garments, as St. Ephraim teaches us (Word 52): By ordinary garments, he says, one who covers himself cares to clothe himself in spiritual attire. But he who adorns himself with multicolored garments strives to be naked of divine clothing. For covering is required of us, but not variegation. The meaning of clothing is one—to be a veil for the flesh (St. Nikon of the Black Mountain, Book 1, Word 37). And again: Wear clothing down to the calves (long to the middle of the shin), neither variegated nor adorned with worldly things. And we must fear such spiritual nakedness and guard ourselves from heretical customs in clothing. Likewise, women are commanded to dress according to Christian custom, and not as Latin women wear indecent attire, baring their breasts and even their shoulders, and thus the wretched ones place the sign of the cross on a single chemise (shirt—underwear), not fearing the prohibition of the holy fathers, that a woman should not, as they said, place the sign of the cross on the chemise except in great need: when washing, or lying down, or rising—then it is without sin. But let her not stand in prayer in a single chemise or with uncovered head, for this is abominable to God”3Red Ustav, part two, folio 3..

To those who do not follow the paternal instructions on decorum in clothing, Scripture directly threatens prohibition and excommunication from the Church: “Now many of our Christian women and men are mired in these same heresies. Those who do so shall be prohibited, and if they do not obey, let them be cast out from the Church and from communion with the faithful. And if after much instruction and admonition they do not cease and do not submit to the Church, but continue their wicked custom, let them be accursed, and those who commune with them shall be excommunicated. Such ecclesiastical punishment applies not only to simple people, but also to the clergy, as stated by Nikon of the Black Mountain in Book 1, Word 37, and by Sevastos Armenopoulos in Book 1. Bishops or clergy who adorn themselves with red and bright (in modern terms—fashionable and bright) garments should be corrected; if they persist in this, they are to be prohibited and deposed. The same is said in the book of Apostolic Discourses of St. John Chrysostom (Epistle to Timothy, Moral Instruction 8) ‘On women who adorn themselves with garments for prayer.’ ‘When coming to pray to God, do you clothe yourself in golden braids? For you have come as if to a festival, or as if to a display? Or to join in marriage? But you have come to ask and pray for sins, to beseech the Master to be merciful, desiring to arrange that. Why do you adorn yourself? This is not the image of those who pray. Adornment with garments is no small sin, but a very great one, sufficient to anger God, sufficient to destroy all the labor of virginity. Truly, adornment with garments is the devil’s hook’ (Great Synodicon, folio 116). From which the holy fathers deterred by all means, sometimes with excommunication and prohibition and threats of anathema, sometimes, according to the apostolic word, handing over to Satan for the destruction of the flesh. As related in the old-printed Patericon, chapter 130: ‘They brought to Father Isaiah from Alexandria a nun fiercely possessed and suffering, and begged the elder to have mercy and heal her, for the demon was fiercely devouring her flesh. Seeing her suffering thus, the elder made the sign of the cross and forbade the demon. The demon replied to the elder: I will not obey you nor come out of her, for I entered her unwillingly. This one whom you see is pleasing to me; I taught her to adorn herself shamelessly, and through her I ensnared and wounded many. It happened once that your fellow ascetic Daniel met her after she had bathed in the bathhouse, and sighing to God and praying that He send punishment upon her, so that she might be saved and other nuns live chastely, having learned from her example. God heard his prayer and allowed me to enter her.’”

Thus are people tormented even in this life for adornment with garments, and what will be in the future age for it—if anyone wishes to know, let him labor to seek it in Holy Scripture. For proper prohibitions from the holy Church lie upon those who wear clothing not according to their rank and outside Christian custom.

On this, see: “Nomocanon, chapter 17.” “Rule 71 of the Sixth Ecumenical Council.” “Stoglav, chapter 90.” “Sevastos Armenopoulos, Book 1, section 3, heading 2.” The same “Book 5 from answers to the charter-keeper Nikita the archbishop, and also on those wearing pagan foreign and heretical clothing.”

The prophet Zephaniah says (ch. 3): “Fear before the face of the Lord God, for the day of the Lord is near, and I will punish the princes and the royal house, and all those clothed in foreign garments.” And again it is said (Dioptra, part 1, chapter 16): “Let no one introduce new inventions in garments, but let him fear the fearful Judgment of God. And many other testimonies are found in Holy Scripture prohibiting unusual and variegated clothing, which it is inconvenient to relate in detail here; let us say only this: that for unusual clothing—of Germans and other heretics—it calls them demons and devils. And Christians do not avoid this comparison who imitate ungodly heretics in clothing and other customs”4Red Ustav part 2, folios 3 to 7..

One can also read about Christian clothing in the book by G.E. Frolov “The Path Leading a Christian to the Forgiveness of Sins” in chapters 57 “What Clothing Should a Christian Have,” 58 “Conciliar Prohibition of the Holy Fathers on Dressing in Improper Clothing and Using Fragrant Ointments,” and further from 59 to 61.

What Does Appropriate Clothing Look Like?

Some assert that since we cannot dress like the apostles, there is no point in investigating this. But thanks to the continuity from the fathers, traditional garments in which they prayed and worked have come down to us. For us here, it is important to understand that, of course, there can be no complete analogies with apostolic times and attire. Nor is this necessary. But despite all external historical and national differences, our clothing must be befitting the Christian calling and serve the same purpose as during the time of Christ and the apostles. As seen from many quotations in Scripture and Christian canons, the main purpose of clothing is to be modest, not seductive, not attracting undue attention to persons of both sexes.

Now it is very important to recall that Christianity, coming and enlightening nations with the light of the true Faith, did not at all strive to necessarily unify the cultural customs of peoples, forcing them into a single external form—for example, Greek (Mediterranean) or Jewish (Near Eastern). Christianity accepted suitable cultural models, filling them with new, higher content. This is what happened in Rus’ with regard to clothing, as it fully suited Christian life and could symbolize Christian images. For example, the cross-shaped form of shirts for men and women, the division of lower and upper parts by a belt, the symbolism of the right and left sides.

It is interesting to note that practically all national clothing of peoples who converted to Orthodoxy (within the Roman Empire and even beyond) had a sufficiently chaste appearance and was acceptable for Christians. The cut of the traditional clothing of these peoples was preserved over many centuries, usually until the time of complete secularization and loss of tradition. In Rus’, this lasted until the Petrine reforms (among the people, it persisted until the revolution), in the West—until the Renaissance era.

Evidence of the attitude toward clothing in pre-schism Russia is that the same cut was used by the tsar with his boyars and by the simple peasant. They differed only in price, richness of fabric and trimming, as well as decorations and regalia corresponding to status.

However, while carefully preserving and honoring proper traditional Christian clothing, one should not become excessively carried away to the detriment of Christ’s teaching, reducing it merely to the folkloric side.

Thus, let us begin the account of the outward appearance befitting a Christian with Russian folk clothing, since it serves as the starting point in revealing the concept of Christian attire. It should be noted that the task of this article is not to examine the entire diversity of Russian folk costume. We are primarily interested in the traditional archaic forms of folk clothing, which were more stably preserved over the vast territory of the Russian North (Olonets, Arkhangelsk, Novgorod, Vologda, and partly Perm provinces). It is known that it was in these regions that the Fedoseevian and Old Pomorian communities and monasteries were originally located. “The disciples of the Solovetsky elders Daniil Vikulin and Andrey Denisov, together with Korniliy Vygovsky, founded in 1694 the famous Vyg community, renowned in the history of Old Belief”5Maltsev A.I. Old Believer Priestless Concordances in the 17th–early 19th centuries. Novosibirsk: ID “Sova.” P. 25.. “In the Novgorod lands, local fathers enjoyed great authority: the hieromonk Varlaam…”, “as well as Iliya, a former priest from Krestetsky Yam. Among their disciples and followers in the 1690s, the most active was Feodosiy Vasilyev…”6Ibid. P. 26..

Based on scientific research and literary sources, we have attempted to approximately outline for all those interested—primarily Old Believers—the origins and forms of the cut of Christian clothing. In our view, due to the circumstances (lack of hierarchy, celibacy), the prayer clothing of Old Pomorians stands, as it were, in the middle—between folk clothing and pre-schism monastic vestments.

Russian Folk Men’s Costume

The main elements of men’s clothing were: the shirt, trousers (ports), head covering, and footwear.

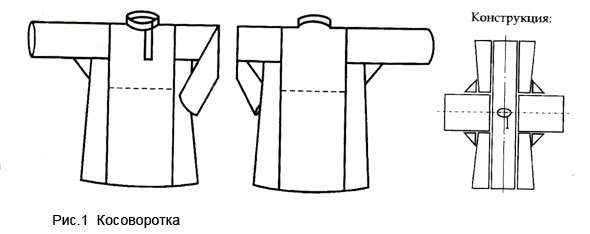

The ancient East Slavic shirt was of tunic-like cut, with long sleeves and a straight slit from the neckline—that is, in the middle of the chest—without a collar, called “goloshveyka” (bare-neck). Later appeared the kosovorotka—a shirt with a slanted slit on the left (rarer on the right) and with a stand-up collar (fig. 1). The “goloshveyka” was subsequently used as an undergarment, worn beneath the upper shirt and not removed at night, like the belt. Our pious ancestors considered it impermissible even to sleep naked. For, in the words of the Savior: “In whatever I find you, in that I will judge you,” and even at night one must be ready to appear before the Judge in a decent form.

To ensure freedom of arm movement, rectangular pieces of fabric—gussets—were sewn between the sleeves and side inserts (panels). A characteristic feature of the men’s folk shirt is the lining of canvas in the chest area, called the podopleka, which extends front and back in a triangular or rectangular projection.

The length of the shirt was a sign of age difference. Shirts for old men and children reached the knees or even lower, while for adult men they were 10–15 cm above the knees. By the end of the 19th century, during the height of secularization, the length of shirts—and especially in cities—shortened significantly (to wear under a jacket).

Shirts were sewn from linen or hemp canvas, pestryad’ (checkered or striped linen fabric), dyed canvas fabric—naboyka, and later—from factory cotton materials. The color of fabric for work shirts was dark, while for prayer it was white. The hem and cuffs could be decorated with embroidery, an ancient form of which is “brannaya” embroidery (in black and red). Ornament covered the lower sleeves, neckline, and hem. Along with patterned weaving and embroidery, festive shirts were decorated with braid, sequins, gold galloon, buttons, and beads. Men’s festive shirts, in richness of decoration, were not inferior to women’s. However, shirts for prayer—both men’s and women’s—had no decorations.

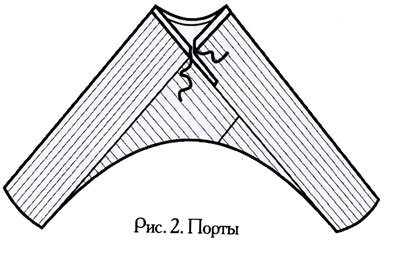

Figure 2 depicts ports (trousers) of Russian cut. They were sewn from striped pestryad’, naboyka, plain canvas, and homespun wool—depending on the season. They were tied at the waist, or more often at the hips, with a gashnik cord or rope. There were also under-trousers—for sleeping.

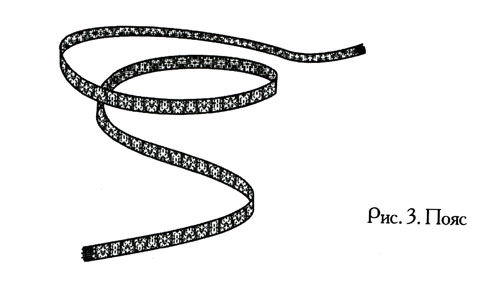

The belt is an obligatory element of both men’s and women’s traditional Russian costume (fig. 3). Belts were made using techniques of braiding, weaving, and knitting. One of the most common motifs in belt patterns are ancient “solstice” (solar) ornamental motifs, which in Christian symbolism signify the Sun7A frequently occurring symbolic image of Christ in patristic theological and instructional writings, as well as in liturgical texts. For example, the troparion for the Nativity of Christ: “Thy Nativity, O Christ our God, hath shone upon the world the light of reason; for thereby those who served the stars were taught by a star to worship Thee, the Sun of Righteousness, and to know Thee, the Orient from on high. O Lord, glory to Thee.” of Truth, the Lord God Jesus Christ. Belts were also made with a prayer to the saint whose name the person bore.

“The most ancient were belts made from linen or woolen threads, woven on fingers and having a rhomboid pattern. The width of belts varied from 5 to 20 cm, and the length from 1 to 3 m”8Russian Traditional Costume. Illustrated Encyclopedia. Authors-compilers: N. Sosnina, I. Shangina. St. Petersburg: “Iskusstvo–SPB.” 1998. P. 284.. Festive belts were wider and brighter than everyday ones. For a Christian, the belt is not merely an attribute of clothing but carries deep symbolic meaning. It represents both the division of lower and upper parts and readiness to serve God. Without a belt, one cannot pray or go to sleep. Thus, there are two types of belts—lower and upper. The lower belt is simpler and unadorned.

Since an Orthodox Russian person did not undertake any task without a belt, this attitude toward a person neglecting such a custom sanctified by antiquity has been preserved in the language. For example, the word raspoyasat’sya means: 1. To untie one’s belt. 2. To become dissolute, to lose all restraint9Ozhegov S.I., Shvedova N.Yu. Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language. Institute of the Russian Language named after V.V. Vinogradov RAS. Moscow: Azbukovnik. 1999. P. 661.. “Walking without a belt is a sin,” people said. To raspoyasat’ (unbelt) a person means to dishonor him. Hence, one behaving unworthily was called in the folk tradition raspoyasavshiysya, that is, voluntarily depriving oneself of honor. “The belt is considered even now a sacred object… and is not removed either by day or by night, except in cases when one needs to go wash in the bathhouse”10Lebedeva A.A. The Significance of the Belt and Towel in Russian Family and Daily Rituals of the 19th–20th Centuries.. “In the daily life and rituals of the Russian people, great importance has long been attached to the belt. For a man to be without a belt was considered extremely indecent in public, in society. The removal of the belt at a feast offended Vasily Kosoy, grandson of Dmitry Donskoy (mid-15th century), which served as a pretext for war”11Solovyov S.M. History of Russia from Ancient Times. Moscow, 1960. Book 1. P. 1055.. There was a proverb among the people: “Why do you walk without a belt, like a Tatar?!” That is, a person walking without a belt, in the folk consciousness, becomes not only non-Christian but even non-Russian. Moreover, people walking without a belt were considered sorcerers connected with unclean forces. “It is indicative that the absence of a belt is a sign of belonging to the chthonic (lower, animal, in this case demonic—V.S.) world: for example, rusalki (water nymphs) are traditionally described as (…) dressed in white shirts, but the absence of a belt is always emphasized. In rituals associated with communion with ‘unclean forces’ (demons—V.S.), the belt was removed simultaneously with the cross.” “The belt tied on a person turns out to be the center of his vertical structure, the place of connection between the sacral upper and the material-corporeal lower…”12V. Lysenko, S.V. Komarova. Fabric. Ritual. Person. Traditions of Weaving among Eastern European Slavs. St. Petersburg, 1992..

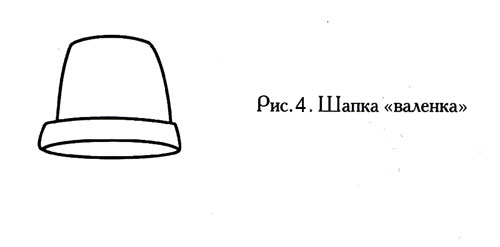

The main head covering for men was the cap (shapka). An ancient type of head covering among the Great Russians is considered the felt cap—“valenka” (fig. 4), “a head covering for spring, summer, autumn made of felted sheep’s wool in white, gray, brown color. They were made in the form of a truncated cone with a flat or rounded top about 15–18 cm high, with turned-up brims or high brims fitting the crown”13Russian Traditional Costume… P. 40.. Peasants wore felt caps, as well as lower round caps with fur trimming. Wealthy people made caps from satin, sometimes with trimming decorated with precious stones and sable fur.

By the 20th century, hats of practically modern form began to be worn. But a Christian necessarily wore a head covering; when bidding farewell, he would remove it, say a prayer, and then put it on again. Forbidden for Christians were only kartuz caps and malakhai caps (Tatar) and treukhi (ear-flap hats). Also caps made of dog or wolf fur, especially for attending communal prayer.

Russian Folk Women’s Costume

One of the main elements of women’s folk clothing is the shirt (rubakha).

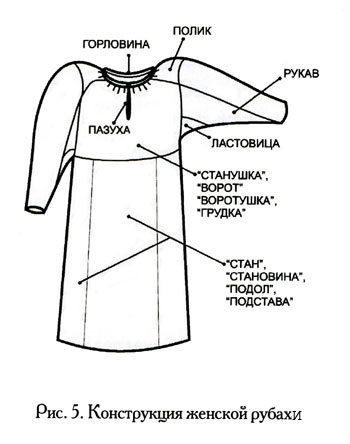

Structurally, the shirt consists of the stan (body) and sleeves (fig. 5). The stan was made from panels of fabric running from the neckline to the hem, in most cases not whole but composite—with transverse division. The upper part of the stan was called differently in various places: “stanushka,” “vorot,” “vorotushka,” “grudka.” The lower part of the stan was called: “stan,” “stanovina,” “stanovitsa,” “pododol,” “podstava.” The horizontal division of the stan was located below the chest level and above the waist level. In width, the stan was made from whole lengths of canvas, whose width varied from 30 to 46 cm, depending on the design of the weaving loom. The voluminous form of the shirt, the width and density of gathers at the neckline, and the volume (fullness) of the sleeves depended on the number of panels used.

Shirts were made from linen, hemp, cotton fabrics; heavier ones—from woolen cloth and wool. The upper and lower parts of the shirt, as a rule, were sewn from fabrics differing in quality, color, and pattern. For the upper part of the shirt, better-quality and more colorful fabrics were used; sleeves and poliki (shoulder inserts) were usually decorated with patterned weaving in red threads, and various embroidery techniques were applied. The neckline of the shirt and the pazukha (20–25 cm) were finished with edging, most often red. The neckline cut was fastened with a button and loop.

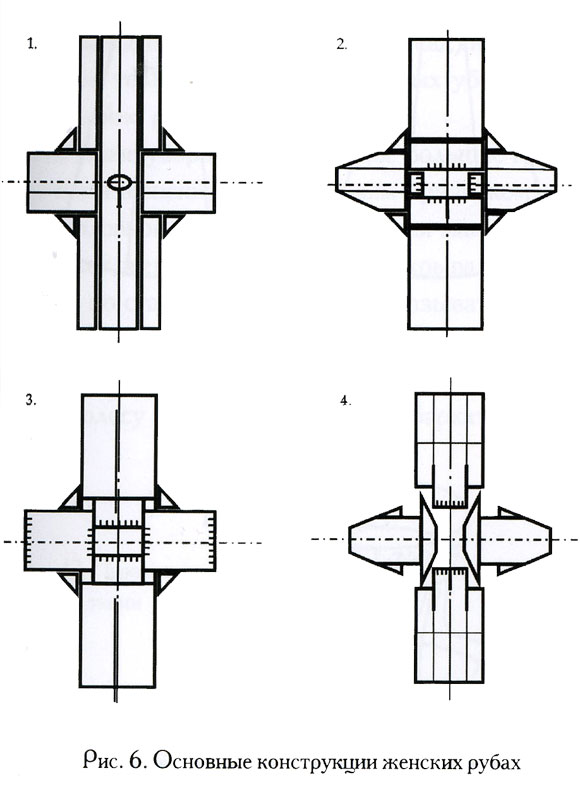

There are four main constructions of women’s shirts (fig. 6):

- Tunic-like (archaic type).

- Shirt with straight poliki.

- Shirt without poliki.

- Shirt with oblique poliki.

The folk shirt could serve as an independent element of women’s costume (for example, the “pokosnitsa” shirt for haymaking), in which case it was necessarily belted with a woven belt and supplemented with an apron. But in the Red Church Statute, Christians were forbidden to walk in a single shirt, and especially to pray in one. A sarafan was worn over the shirt. In southern regions of Russia, instead of a sarafan, a poneva—a rectangular panel gathered at the upper part—was worn over the shirt. The poneva was wrapped around the waist. Like men, women wore a lower, under-shirt, which was not removed at night and was belted with a lower belt.

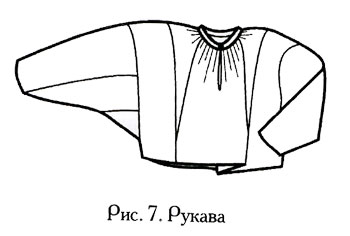

In fig. 7, we see rukava (sleeves, or a type of upper garment). The types of sleeve constructions are the same as in the folk women’s shirt; their distinctive feature is the absence of the lower part of the stan. Rukava were worn over the belted under-shirt, followed by the sarafan—the second main element of the folk women’s costume.

The sarafan has many names derived from the fabric from which it was made (shtofnik, shelkovik, atlasnik, kashemirnik, sitsevik, sukman, kumashnik, samotkannik, etc.); names from the sarafan’s construction (klinik, kosoklinny, semiklinny, sorokoklin, krugly, lyamoshnik, etc.); from the color and pattern of the fabric (sandal’nik, marenik, nabivnik, pestryadil’nik, kletovnik, troekrasochniki, etc.). “The most ancient of them (sarafan—from Iranian ‘sarapa’ or ‘sarapai’—clothed from head to feet) was the deaf (closed) kosoklinny sarafan, which existed in a number of provinces until the end of the 19th century under names such as shushun, sayan, feryaz’, dubas, etc.”14Russian Traditional Costume… P. 284..

Over time, the sarafan changed structurally, the fabrics used for it changed, and new names appeared. In general, the entire diversity of this type of clothing reduces to four main types of sarafans:

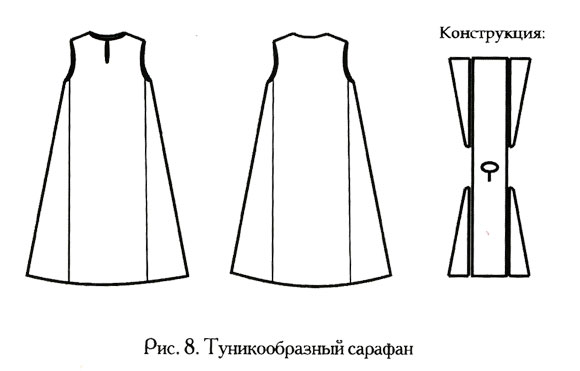

- Deaf (closed) tunic-like, of the most ancient type (fig. 8).

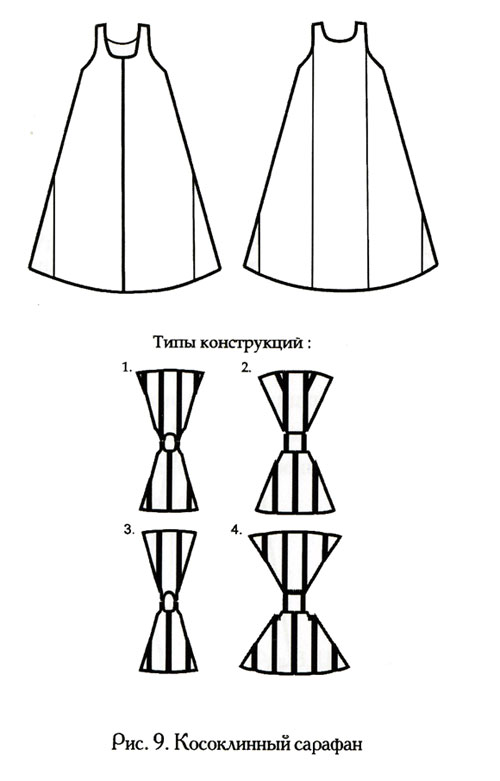

- Kosoklinny (oblique-wedge) (fig. 9).

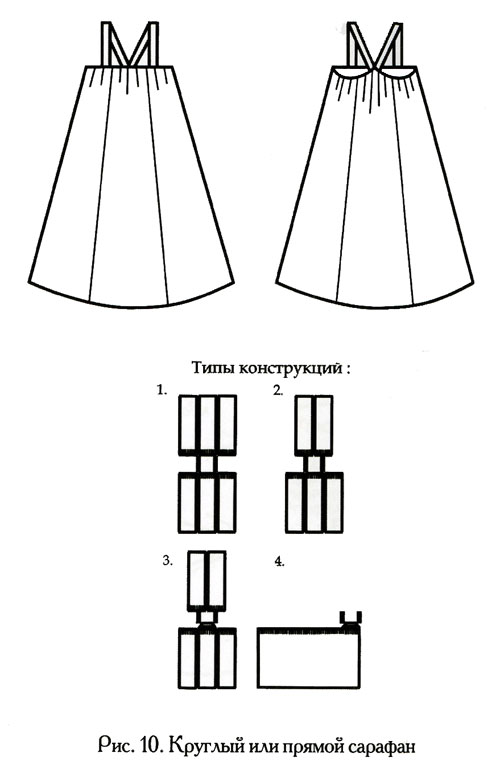

- Round or straight (fig. 10).

- Sarafan with a bodice. (The latest type of sarafan, not considered in the context of this article).

- The deaf tunic-style sarafan represents an archaic form and construction. It was sewn from one piece of fabric folded in half, forming the front and back panels of the sarafan. The sides were widened with longitudinal wedges or slightly slanted panels of fabric sewn in along the entire length from small oval armholes to the hem. A shallow neck cut was made in the center of the folded panel, round or rectangular in shape, with a small chest slit (opening), fastened with a button or tied.

- The kosoklinny sarafan, by the construction of the front panel, is divided into deaf, open-front, and with a central front seam. The deaf kosoklinny sarafan is a transitional form from the archaic tunic-like sarafan. The open-front or with central front seam sarafan was sewn from three straight panels of fabric (two in front and one in back) and two to six wedges on the sides. The front flaps were fastened with metal buttons and loops or sewn together; the central front seam and hem were decorated with gold galloon, braid, embroidery, fabric appliqué using sequins, glass beads, river pearls, etc. The quantity and value of decoration depended on the purpose of the sarafan. The straps of the sarafan could be cut in one piece or made from a separate piece of fabric. The edges of the straps, neck cut, armholes, and hem were edged with strips of fabric or braid.

Fig. 9. Kosoklinny sarafan

- The main distinction of the straight or round sarafan is the whole straight panels of fabric gathered at the upper edge. In such sarafans, either all panels are of equal length, forming a kind of skirt on straps, or the front panel is elongated in the upper part, reaching almost to the neck and covering the entire chest. Narrow straps are cut from the same fabric as the sarafan and edged with strips of plain colored fabric. The round sarafan at the bottom could be supplemented with one or several rows of frills, edged with braid or lace.

Fig. 10. Round or straight sarafan For all types of sarafans, the hem was doubled on the wrong side with plain fabric, 7 to 20 cm wide. The kosoklinny and tunic-like sarafans, to give a rigid shape and for warmth, could be sewn entirely with lining. Everyday sarafans were sewn from simple fabrics and almost undecorated. Festive sarafans were made from precious and semi-precious fabrics and richly decorated. When worn, both on holidays and weekdays, a zaveska, zanaveska, zapon, or apron was put on over the sarafans (fig. 11). Later, it acquired practically the modern form of an apron. And over the zaveska, the upper belt was tied. Thus, the clothing was three-layered: the shirt with the lower belt, the sarafan, and the apron with the upper belt.

Fig. 11. Apron The ensemble of women’s folk clothing is unthinkable without a headdress, to which special attention was paid in folk culture. By the headdress, one could tell the region of its owner, her age, marital and social status. Almost every province (and sometimes district) had forms of headdresses unique to it. They are extraordinarily diverse.

Fig. 12. Headband Headdresses are divided into two large groups: maiden’s and married women’s. A characteristic feature of maiden’s headdresses was an open crown, while married women completely covered their hair, as by ancient custom it was forbidden to show them. Maiden’s headdresses include the fabric headband (fig. 12), which “was a strip of fabric (silk, brocade, velvet, kumach, galloon) on lining… width from 5 cm to 20–25 cm, length up to 50 cm. The band was worn on the crown or forehead and tied under the braid at the nape. Two lobes of silk or brocade were sewn to the back…”15Russian Traditional Costume… P. 223.. Also: a hoop of wood bark or cardboard, a venets (crown), a venok (wreath), a plat (scarf), a knitted cap.

Women’s headdresses include:

- Towel-type headdresses (polotentse, nametka, ubrus) in the form of a long towel with or without decoration, wound in a special way over a cap with a round bottom, a chepets, or a kichka.

- Kichka-type headdresses (kichka or soroka), distinguished by diversity and fanciful design. As a rule, composite. Main elements: lower part with a hard base giving shape to the headdress (kichka, horns, volosnik, etc.); upper decorated part of fabric (soroka, verkhovka, privyazka, etc.); pozatylynik of fabric tied at the back under the upper part. The kichka-soroka was supplemented with other elements: nalobnik, bead pendants, feathers, “naushniki” (earpieces), cords, silk tassels, etc.

- Kokoshnik — a festive headdress richly embroidered with gold and silver threads, sewn with river pearls, decorated with sequins, multicolored glass, cannetille, glass beads.

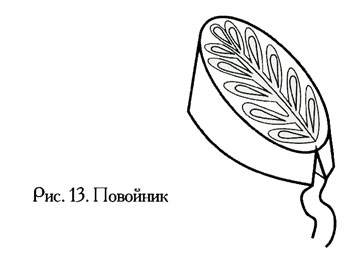

- Povoinik, sbornik (fig. 13). One of the ancient headdresses in Rus’, in the form of a soft cap completely covering the hair. The povoinik was an under-headdress, always covered from above with an ubrus or volosnik; it was not proper to walk around the house, let alone on the street, in just a povoinik. From the second half of the 19th century, it acquired independent significance. Everyday povoiniki were sewn from simple materials, festive ones from expensive fabrics, with the bottom decorated with gold embroidery, river pearls, sequins.

Fig. 13. Povoynik In our Old Pomorian tradition, all the above-listed headdresses are completely absent. This is connected with the celibate status in recent times16Interestingly, in the Trebnik there is a special priestly prayer for the povoinik..

- A widespread headdress is the plat (shawl/scarf). Shawls were worn by both girls and women at different times of the year. They gave the costume special colorfulness and uniqueness.

Footwear

Folk footwear can be divided into the following groups:

- Woven footwear (lapti, bast and birch-bark shoes, half-boots, and boots). Lapti were the most common and cheapest summer (and sometimes winter) footwear. Materials were lime, elm, rarer willow bast, and birch bark.

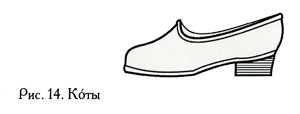

- Leather footwear (boots, botinki, shoes). Leather footwear was widespread in Russian villages, though not every peasant could afford it. Leather botinki and shoes (koty, chary, choboty, khodoki, chereviki, etc.) — rigid construction footwear with heels. 19th–early 20th century koty (fig. 14) — women’s festive footwear, worn with stockings, sometimes fastened to the leg with straps or laces passed through eyelets on the uppers or heels.

Fig. 14. Koty

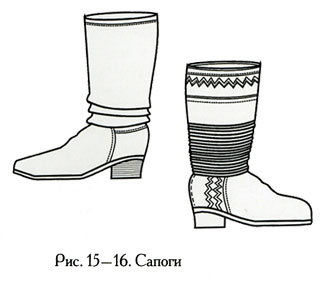

Traditional Russian folk leather footwear — sapogi (boots) (figs. 15, 16) — gained wide popularity. Boots were made vyvorotnye (with sewn-on tops) or vytyazhnye (whole), with naboyki or high heels (a copper horseshoe was sewn to the heel). The shaft was sewn either “v garmoshku” (gathered in fine horizontal folds) or rigid and smooth on top, gathered in folds near the head.

In some localities, boots were important as work footwear (for example, in the Russian North, in Siberia). These are distinctive boots with sewn-on high shafts, loops, and straps for fastening to the leg — brodni, bakhily, bredni, lovchagi (fig. 17).

Festive leather footwear was decorated with metal pistons forming simple patterns; stitched with threads, finished with appliqué — overlays of leather and other colored material.

Russian Folk Outer Clothing

Outer folk clothing refers to all shoulder garments worn by Russian peasants over the shirt, sarafan (or poneva), and apron. Women’s outer clothing hardly differed from men’s in construction, the differences being in details, sizes, and degree of decoration. Both women’s and men’s outer clothing wrapped in the same way — the right panel deeply overlapping the left, not by chance, for in ancient Christian tradition the primacy of right over left can be seen from the beginning. In this series stand the Orthodox sign of the cross, walking posolon’ (sunwise), and the position of hands in prayer17See: Uspensky B.A. The Cross and the Circle: From the History of Christian Symbolism. Moscow: Yazyki slavyanskikh kul’tur, 2006.. Accordingly, when making outer clothing, the right panel was often made 5–10 cm longer than the left, the placket line oblique. The fastening was mainly up to the waist line: buttons or hooks on the right panel, loops on the left.

Outer folk clothing is very diverse. By way of wearing, two types are distinguished: thrown over the shoulders (cloak, cape) and, most characteristic, put into sleeves; the latter divided into deaf (closed) and open-front (raspashnaya).

Traditional outer clothing has many names. Common Slavic: svita (from “svivat’” — to twist), gunya, koshulya, kabat, kozhukh, etc. Ancient Russian terms: ponitok, sukonnik, opashen’, okhaben’, odnorjadka, etc. Russian names: poddyovka, kutsinka (from “kutsiy” — short), shugay, korotay, semishovka, verkhovitsa, etc. Terms of Eastern origin: kaftan, zipun, shuba, tulup, armyak, etc.

Kaftan-zipun (fig. 18), open-front outer folk clothing. Made from homespun cloth or factory fabric, most often brown, rarer black or gray. The back of the zipun is whole, slightly fitted or cut-off with gathers. Two or three wedges were sewn into the sides, sleeves cut-out. The zipun was made without a collar or with a small collar fastened with one or two buttons (at the neck and chest). Sleeve edges were often edged with leather, and sometimes (in women’s zipuns) with plush. The zipun was usually made without lining. It was worn, depending on the weather, in all seasons.

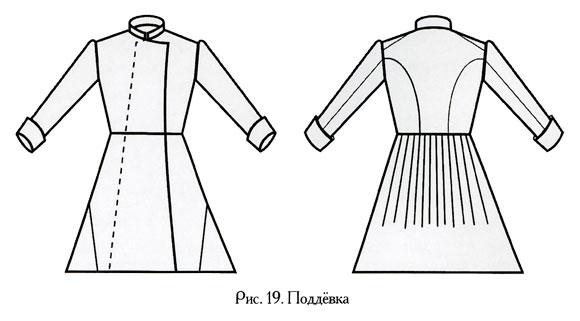

Poddyovka (fig. 19), as the name suggests, was worn under another, warmer garment. For this type of outer clothing, thin homespun cloth or “ponitchina” (warp linen, weft wool) was used. A feature of the cut can be considered the cut-off waist and gathers on the back of the poddyovka. Also a shoulder seam dropped back and arc-shaped darts on the back (preserved to this day, for example, in military or police short sheepskin coats), stand-up collar. From the neck to the waist were four hook fastenings. The length of the poddyovka reached mid-calf. The ponitok had a similar cut, only without gathers at the back waist.

Short clothing has been considered impermissible and even law-breaking since Old Testament times, like beard-shaving18Collection on Worldliness and Beard-Shaving. Printing House at the Preobrazhensky Almshouse in Moscow in the year 7419 (1911). Folio 24.. In the Bible it is said: “And Hanun took David’s servants, and shaved them, and cut off their garments in the middle, even to their buttocks, and sent them away. Then certain came and told David about the men; and he sent to meet them, for the men were greatly ashamed”19First Book of Chronicles, chapter 19, verse 4..

Short — “shchapovataya” — clothing is also forbidden to wear in the well-known book of the early 19th century compiled from Scripture by “the abbot of blessed memory of the Kineshma regions Trofim Ivanovich, native of Moscow and spiritual son of Ilya Ivanovich, who ended in exile and glorified by incorruption.” “Short clothing, called telogreya, this is un-Christian attire, that is, pagan, or again women sewing men’s clothing for themselves or putting ready-made on themselves. Or again men and women keeping and wearing Circassian clothing, and not counting it a sin, some even standing in prayer in them”20Statute on Christian Life. On Walking in Clothing Unbefitting Christians. If a man or woman clothe themselves in attire not according to paternal tradition, let them be anathema. Chapter 34..

Clothing for Prayer

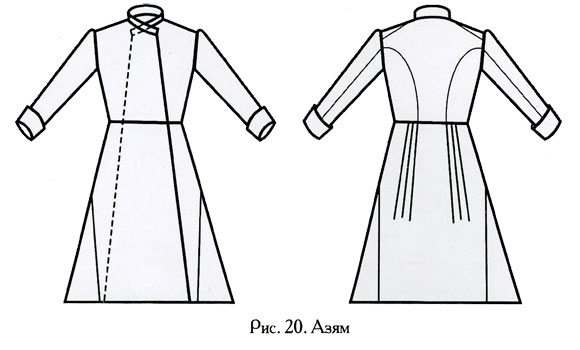

Until now, we have considered everyday, worldly or secular clothing, and in it it was considered impious to come to communal prayer. For prayer, there was a special cut long, to the ground azyam. Now, unfortunately, in the time of general mixing and loss of tradition, the poddyovka in many places has come to be considered church clothing. And to give it “solid churchliness,” it is simply lengthened like an azyam. Meanwhile, there are conciliar paternal prohibitions for Old Pomorians to come to prayer in poddyovkas: “in poddyovkas at prayer by no means to stand.”

In fig. 20 is depicted the azyam — men’s outer clothing for communal prayer, accepted among Old Pomorians (Fedoseevtsy and Filipovtsy). Features of the azyam’s cut are recorded in the Statute for the Preobrazhensky Almshouse of Ilya Alekseevich Kovyline. The color can only be black, dark brown, dark gray, or dark blue. The azyam has a cut-off waist, shoulder seam dropped back, and arc-shaped darts on the back, like the poddyovka. But the collar is no longer just a stand-up but continues along the entire upper line of the front. On the back from the waist, under the lower edge of the darts, go three counter folds each 7–9 cm deep, almost one above the other.

The length, as mentioned above, reaches down to the footwear. A striking distinctive feature of the azyam was the red twisted “snurok” (twisted cord), with which the cuffs and the entire front panel from the side were edged, including the collar and hanging loops. From the loops, four fastenings were formed with two round buttons each from the collar to the waist. Such fastenings can be seen in old portraits in the city of Riga in the Grebenshchikov community. However, closer to the 20th century, these fastenings ceased to be made, and they switched to ordinary hooks as on secular or military clothing. Interestingly, by the 20th century, the twisted cord also disappeared from azyams, but edging of black velvet appeared on the cuffs and collar (possibly only for kliros members).

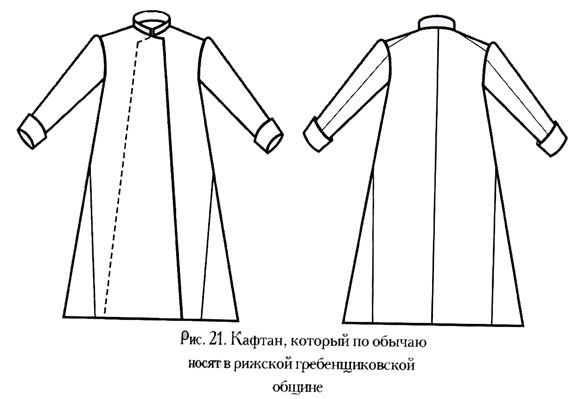

In fig. 21, as an example, a kaftan is shown, which by custom is worn in the Riga Grebenshchikov community. It is dome-shaped: there are neither folds nor darts, neither in front nor in back. This is most likely ancient outer clothing, under which an azyam or poddyovka was worn. A sample of it can be seen in the Historical Museum, where a velvet kaftan of this cut is displayed in a showcase.

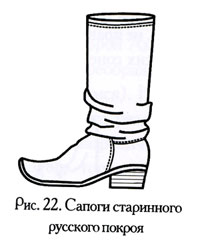

In fig. 22, we see boots of ancient Russian cut: with turned-up toes and on heels. Such boots were worn during services, as seen in the same old photographs. There is also a prohibition against wearing “smaznye” boots, that is, shiny—patent leather—as well as boots without heels—in the Tatar style.

Women’s clothing for prayer also has its distinctive features that set it apart from traditional folk clothing. The complex of women’s prayer clothing consisted of the following elements: lower shirt belted with a belt, rukava (sleeves or upper bodice) worn over the lower shirt, sarafan, two shawls (lower and upper).

The sarafan for prayer (fig. 23) is an open-front kosoklinny sarafan with a collar like that of the deaf tunic-like sarafan. Its distinctive feature is three pairs of counter folds laid from the collar to the middle of the shoulder blades and stitched on the back. The front panels are fastened with buttons and hanging loops. The number of buttons must be a multiple of numbers symbolic for Christians (as on the lestovka, for example): 30, 33, 38, 40. Thus, even the buttons on the prayer sarafan were not decoration but reminded of truths significant in the Christian way of life. The hem of the sarafan at the back should lie on the ground, like a small train. The front part is shorter, so that the toes of the footwear are visible. For prayer sarafans, fabric in dark blue, dark brown, or black colors was used. Red in all shades was forbidden. It must be emphasized that sarafans for prayer are not belted (Article 41 of the Polish Council).

Under the sarafan was worn the lower shirt with a belt, and over it rukava (manishka) exclusively white in color (and not whatever one wants or happens to have!—V.S.). The wide sleeves of the shirt were gathered at the wrist or ended in a cuff and decorated with white lace. In Kazan, for prayer, it is customary to wear a white shirt with wide ungathered sleeves, also decorated along the edge with white lace (fig. 24).

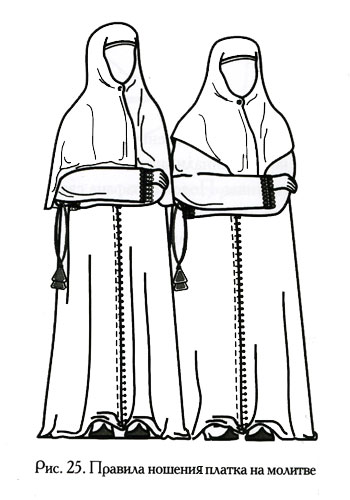

An essential element of women’s prayer clothing is the shawl. First, the woman puts on the lower white shawl, completely tucking away the hair and covering the forehead to the middle. Then the head is covered with the upper shawl. There are special rules for wearing the shawl in prayer (fig. 25). Unmarried praying women (maidens and widows) wear the shawl loose, on the edge (image on the left). For praying women, fringes (bakhroma) along the edge of the shawl are unacceptable. Married women wear the shawl only cornerwise (image on the right). Let us recall that non-praying can include not only married women but also those excommunicated from communal prayer for other deviations or transgressions. In prayer, the shawl is not tied in a knot but is necessarily pinned under the chin with a fastener (in antiquity, this was most likely a fibula; now a simple safety pin). The color of the shawl, like the sarafan, is exclusively dark.

As regrettable as it is, nowadays we see complete multicolored variety in clothing and shawls among non-praying women. One should not follow the example of the “married” (those in marriages) and wear now white, now colorful shawls—this is entirely non-traditional for Pomorians, and especially for Old Pomorians. “The communal statute developed by Andrey Denisov in 1702 (… ) reflected the desire to eradicate habits of worldly life. In the 1720s, the statute was supplemented by conciliar decrees regulating the character of women’s clothing, prohibiting lace and ‘knitted plaits’ and ‘other improper’ decorations…”21Kapusta L.I. Folk Art of Karelia and Artistic Traditions of Vyg. Culture of Vyg Old Believers. (On the 300th Anniversary of the Founding of the Vyg Old Believer Community). Petrozavodsk: “Karpovan Sizarekset.” 1994. P. 38. And the Vyg Council of 1725 also says in Article 10: “Among all hermitage dwellers in the wilderness, strictly ensure that there be no cornered caps with tassels, no camel-hair or silk sashes, and no draget clothing”22See: BAN. Druzhinin Collection No. 8 and Pushkin House. Collection No. 3. Autograph of Andrey Denisov..

On clothing for communal worship, Article 41 of the Polish Council of 1752 says: “Youths in red shirts and kalamencovy trousers (of fine colorful fabric), and maidens in red boots and red shawls and with gold bindings, by no means to stand in prayer, and not to gird themselves with belts, and thereby not to scandalize the Orthodox (!—emphasized by V.S.); if they prove obedient, let them make 300 prostrations to the ground.”

The St. Petersburg Council of 1809 on clothing, already not only for worship, says: “Article 8. German dress is seen worn by many Christians, and on this there are most terrible prohibitions in divine Scripture. Therefore, superiors must in every way restrain from this soul-harming custom, and excommunicate those who resist.”

The sixth article of the famous Moscow Council of 1883 prohibited what had by then become fashionable non-Christian custom in clothing: “Not to adorn oneself with foreign and pagan garments (…) In such attire, by no means to stand in prayer houses” (this is as topical as ever today!—V.S.).

It must be recalled that even at home, in cell prayer, standing before holy icons, one cannot neglect Christian attire, just as in communal prayer.

At present, among modern Christians, there is an opinion that for newlyweds and other non-praying excommunicated from communal prayer, it is entirely unnecessary to wear Christian clothing either in everyday life or even when coming to communal prayer. And men need not wear beards, nor women uncut hair, and certainly not maintain Christian utensils. “After all, they say, one won’t pray anyway.” But this is utterly unsound, un-Orthodox reasoning. We ourselves, without any persecutions or prohibitions, thereby deprive ourselves of the Christian appearance (likeness of God), reject the holy fathers’ commandments, and do not wish to imitate the lives of God’s saints.

In conclusion, one must acknowledge, following the well-known spiritual father G.E. Frolov: “Here we call ourselves Old Believers, but our outward appearance testifies to the opposite. Often they reply: ‘One must keep the covenants of piety in the soul.’ But this is merely an evasion. Your impious outward appearance… proceeds from your will, from your attachment to everything new and corrupt. Your outward appearance clearly exposes empty inner content. On you is the uniform not of Christ’s warrior, but of Antichrist’s.” “If it is shameful on the street to show oneself as a Christian before the corrupt world, then why do you appear in the prayer house and at Christian gatherings and congresses in Antichrist’s guise? What sound advice can come from such counselors?”23Frolov G.E. Covenants of Antiquity. Calendar for the Year 1999 of Christians of the Ancient Orthodox Catholic Confession and Old Pomorian Concord. Moscow, 1999. P. 47.

From accounts of eyewitnesses of the proper attitude toward non-Christian corrupt clothing, one can cite Natalia Alekseevna Sergeeva (now reposed kliros singer of the Preobrazhensky Cemetery, disciple of G.E. Frolov). When a young man from the city arrived in their village of Rayushi (Estonia) in a fashionable jacket, one of the Christian elders approached him from behind and, pulling from bottom to top, tore the demonic attire. A similar episode was related to us by Kapetolina Platonovna Rokhina, whose great-grandfather Ambrosiy Rokhin was a participant in the council at Preobrazhensky Cemetery in 1883 (though non-praying). In their Christian village of Zubari in Nolinsky district, a certain dandy also returned from the city in “foreign attire,” so his grandfather simply hacked the “Antichrist uniform” with an axe.

Today, alas, we calmly observe, without any qualms of conscience, carefree people clad in these demonic garments walking into Christian churches. Is it really impossible for them to sew at least a Christian shirt for attending services? Of course it is possible! Let them divert a little means and time from worldly occupations in their lives, to at least attempt in this to resemble Christians, as the holy fathers and our pious ancestors called us from the beginning of the Orthodox faith to our last days.

The last among Christians V.G.S. Summer 7515

-The article is taken from the Old Orthodox calendar for the years 2007–2008.