Apostle Andrew #

The centuries-old history of Russia is inextricably linked with Christianity. The Gospel was proclaimed in our lands long before the emergence of the Russian state. Ancient chronicles name Apostle Andrew as the first preacher of Christianity in Russia.

He was a native of the Judean city of Bethsaida and the elder brother of the Apostle Peter. The brothers were simple fishermen, catching fish in the Sea of Galilee.

When John the Baptist began preaching repentance and baptism for the forgiveness of sins, Andrew became his disciple. However, upon meeting Jesus Christ, he followed Him. Andrew’s encounter with the Savior is described in the Gospel. One day, when John saw Christ, he said to his followers: — “Behold the Lamb of God!”

Hearing this, two of John’s disciples, one of whom was Andrew, followed the Lord. Turning around and seeing them, He asked: — “What do you seek?”

They replied: — “Teacher, where are you staying?”

The Savior answered: — “Come and see.”

They went and saw where He was staying, and they remained with Him that day. In the evening, Andrew found his brother Peter and told him: — “We have found the Messiah!”

Later, as the Savior walked by the sea, He saw Andrew and Peter casting nets, and He said to them: — “Follow Me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

The brothers immediately left their nets and followed the Lord. From that time on, they followed Him closely, witnessing His saving teachings and countless miracles.

Andrew became the first-called apostle — the first disciple of Christ. For this reason, he is known as the First-Called.

Along with three other chosen disciples, Andrew participated in the Savior’s conversation about the end of the world. At that time, the Lord warned the apostles about false teachers and preachers to come: — “Take heed that no one deceives you! For many will come in My name, saying, ‘I am He,’ and will deceive many. If anyone says to you, ‘Look, here is the Christ!’ or ‘Look, He is there!’ do not believe it. For false Christs and false prophets will arise and perform signs and wonders, to lead astray, if possible, even the elect.”

The Savior also warned of future persecutions, trials, and sufferings that awaited those who believed in Him: — “They will deliver you up to councils, and you will be beaten in synagogues. You will be brought before governors and kings for My sake, as a testimony to them. But when they arrest you and deliver you up, do not worry beforehand about what you will say, nor premeditate. But whatever is given to you in that hour, speak that; for it is not you who speak, but the Holy Spirit. And you will be hated by all for My name’s sake. But he who endures to the end will be saved.”

After the Lord’s ascension into heaven, the apostles cast lots to determine who would go to which country to preach. The lot fell for Andrew to go to Scythia.

Drawings by B. Kiselnikov

Drawings by B. Kiselnikov

In ancient times, Scythia referred to the northern coast of the Black Sea, inhabited by the warlike Scythians. They roamed with countless herds across the vast steppes from the Danube River to the Caucasus Mountains. A Scythian kingdom existed in Crimea.

On his way to Scythia, the apostle passed through many Greek cities along the shores of the Black Sea, preaching Christ and His Gospel everywhere. Many times, Saint Andrew endured suffering for his faith. He was beaten with sticks, dragged across the ground, pulled by his hands and feet, and pelted with stones. But with God’s help, he bravely endured everything and continued his preaching.

In Crimea, the apostle visited the city of Korsun and the shores of the Bosporus. From there, according to the ancient Russian chronicle, Saint Andrew, together with his disciples, decided to head north — to the lands where the Slavs lived.

The apostle sailed upstream on the Dnieper River. One night, he camped near some high hills. When he woke up in the morning, he stood and said to his disciples: — “Do you see these hills? On these hills, the grace of God will shine, and a great city will arise here, and God will raise many churches.”

Andrew ascended the hills, blessed them, placed a cross, prayed to God, and then descended. Several centuries later, the city of Kiev was founded in that very place.

The chronicle tells that, continuing his travels, the apostle visited the Slavs who lived where modern-day Novgorod now stands. He witnessed how our ancestors used whisks in the bathhouse and was very surprised by this. Later, he recalled: — “I saw a wonder in the land of the Slavs! I saw wooden bathhouses. They heat them strongly, strip naked, pour themselves with kvass, take young branches, and beat themselves. They beat themselves to the point of exhaustion, barely able to crawl out, nearly half-dead. Then they pour cold water over themselves and revive. And they do this constantly, not tortured by anyone but torturing themselves. Yet they consider this a cleansing, not torment.”

During his journeys, Andrew visited the small Greek city of Byzantium, located on the shores of the Bosporus, at the crossroads of the main trade routes between Europe and Asia. There he preached and established a Christian community. In the year 37, the apostle ordained Stachys as a bishop for this community.

Three hundred years later, in 330, the great Emperor Constantine transferred the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium. From then on, Byzantium was known as New Rome, Tsargrad — the city of the emperor, or Constantinople — the city of Constantine. The bishops of Byzantium, the successors of Stachys, became the leading pastors in the Greek lands. From that time on, they were called the patriarchs of Tsargrad.

Tsargrad and the Greek Church hold a special place in the history of Russian Christianity. After all, it was from here that we received the Orthodox faith and the pious priesthood.

From Byzantium, Andrew traveled to the Greek city of Patras, where he converted all the inhabitants to Christianity. It was there that he was destined to complete his earthly journey by enduring a martyr’s death.

Through the laying on of hands, the apostle healed many of the city’s residents from various illnesses, including the wife and brother of the city governor, Aegeates. However, the ruler did not accept Andrew’s preaching and did not believe in Christ. He hated the apostle and ordered him to be captured and crucified. This took place around the year 70.

The Almighty Lord punished Aegeates. The ruler fell from a high wall, crashed, and died.

However, the work begun by Saint Andrew did not perish. It continues to this day. The Gospel faith, proclaimed by Andrew the First-Called, passed from Tsargrad to Rus, to Kiev and Moscow. From there, it entered the Old Belief, which has steadfastly and firmly preserved the traditions, customs, and rites of the ancient apostles.

Old Belief is a remarkable window into eternity. Through it, we can peer deep into the centuries. Through it, the unfading light of original Christianity reaches us.

The Baptism of Rus #

The ancient Slavs, our ancestors, were pagans. They did not know the true God, did not believe in Him, but worshiped the sun and the moon, the sky and the earth, fire and water. The Slavs called the mountains, trees, stones, and all natural phenomena — lightning, thunder, wind, and rain — gods and spirits.

Pagan belief was not good; there was neither love, nor light, nor joy in it, only malice, darkness, and fear. The Slavs made idols out of stone and wood, representing their imagined gods. These idols were honored, prayed to, and offered sacrifices.

From ancient times, the Russian land was vast and abundant. Our merchants traded widely in furs, bread, flax, honey, wax, and swords. Our princes were warlike and successful, and the fame of their victories spread throughout the world.

Rulers of neighboring states wanted to see the Slavs as allies and friends. The city of Kiev, the capital of the ancient Russian state, was visited by ambassadors and merchants from all corners of the world. From the south came the Greeks, Persians, and Arabs; from the east — the Khazars and Bulgars; from the west — the Germans (as all Europeans were called in Rus).

In the 9th century, Slavic tribes began to accept Christianity. During this century, Bulgaria and Great Moravia were baptized. For these newly converted peoples, the brothers Cyril and Methodius, the holy enlighteners and teachers of the Slavs, created a special alphabet and translated church books from Greek.

The first Christians also appeared in Kiev. These were merchants who traded in the magnificent Tsargrad (Constantinople) and accepted Orthodoxy there. The Christians of Kiev gathered for prayer in the church of the Holy Prophet Elijah. But this was only the faint dawn, heralding the rising sun of the true faith over Rus.

The Christian dawn first truly illuminated our land during the days of Saint Princess Olga, who ruled Rus after the death of her husband, Prince Igor. In 955, Olga visited Tsargrad, where she was baptized by the Greek emperor and patriarch.

Despite her efforts, Olga could not convince her son, Prince Svyatoslav, to accept baptism. Svyatoslav was a stern warrior who spent his life on campaigns with his troops and in bloody battles. His warriors were pagans, and he wanted to remain a pagan. To his mother, the prince replied: — “How can I alone accept a different faith? The troops would laugh at me!”

However, Svyatoslav did not forbid any of his warriors who wished to be baptized, though he only made fun of them.

After Svyatoslav’s death and the subsequent princely feuds, in 980, his youngest son, Prince Vladimir, took control of Kiev. He was known as Vladimir the Great to the people, and the Church called him Saint Vladimir.

Like his father, Vladimir worshiped idols, but paganism did not sit well with him. Envoys came to the prince from the Bulgars, Germans, and Khazars, each praising their own faith: the Bulgars — Islam, the Germans — Latin Christianity, and the Khazars — Judaism. Yet none of these faiths appealed to Vladimir.

Then, the Orthodox Greeks sent a preacher. He spoke at length about life and death, about good and evil, about the existence of the world. These words resonated deeply with Vladimir. Generously rewarding the Greek, the prince sent him away and began to ponder. He gathered his boyars and elders and asked: — “The Bulgars, Germans, Khazars, and Greeks have come to me. Each praises their own faith. What do you advise?”

The boyars and elders replied: — “Know this, prince, that no one speaks ill of their own faith, but only praises it. If you want to truly understand these foreign beliefs, send envoys to different lands and nations. Let them learn how each serves God.”

And so, Vladimir sent his envoys, instructing them to study the faiths of all the peoples. The envoys visited many lands, but they were unimpressed with the prayers of the Bulgars and Germans. They saw no joy or beauty in their worship.

However, when the envoys arrived in Tsargrad, the Greek emperors, the co-ruling brothers Basil and Constantine, led them into the majestic church of Hagia Sophia for the solemn patriarchal service: ruby and green lamps shimmered, disordered rows and bundles of candles burned hotly and brightly, choirs praised Christ, fragrant incense smoke wafted through the air, and the gold-embroidered vestments of the clergy glittered.

Overcome with joy, the envoys returned to Kiev and reported to Vladimir, the boyars, and the elders: — “We have visited many peoples, but their faiths are poor. There is no joy or beauty in them. We arrived in Tsargrad, and the Greeks brought us to the place where they worship their God. We were filled with such joy that we did not know whether we were in heaven or on earth. We saw such beauty and glory that we cannot describe it. We only know that God dwells with these people. We cannot forget that beauty, for anyone who has tasted something sweet will not afterward desire something bitter. And we no longer want to be pagans!”

The boyars and elders said to the prince: — “If the faith of the Greeks were not good, your grandmother Olga, who was a wise woman, would not have accepted it.”

Then Vladimir asked: — “Where shall we be baptized?”

And the boyars and elders replied: — “Wherever it pleases you.”

In 988, the prince of Kiev led his army to Crimea, laid siege to the Greek city of Korsun, and demanded that the emperors Basil and Constantine send him their sister, Princess Anna — Vladimir had decided to marry her.

Basil and Constantine responded that they could not give their sister, a devout Christian, in marriage to an unbelieving pagan. Then Vladimir demanded that Anna come to Korsun with a bishop and priests to baptize him.

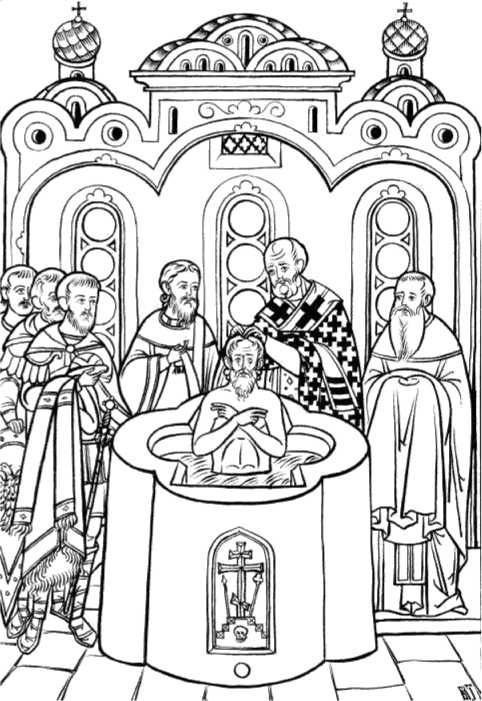

When the princess arrived in Crimea, Vladimir was baptized and was given a new name — Basil. Along with the prince, his boyars and warriors were also baptized. Afterward, Vladimir married Anna.

Upon returning to Kiev, the prince ordered the destruction of all idols — some were chopped to pieces, others were thrown into the fire. The chief idol he commanded to be thrown into the Dnieper. Then he sent a proclamation throughout the city: — “If anyone does not come to the river tomorrow to be baptized, whether rich or poor, old or young, they will be my enemy!”

The next morning, Vladimir went to the Dnieper with priests and deacons. There, a great multitude of people had already gathered. They entered the water and stood — some up to their necks, others to their chests, and some holding infants in their arms. The priests baptized all the people of Kiev, and the prince ordered the construction of holy churches where the idols had once stood.

Thus Kiev was baptized, and with it, all the land of Rus. Churches of God were built throughout the cities, priests served in them, and children began to learn literacy. Greek architects, iconographers, scribes, and hymnographers came to Rus, teaching our people all their marvelous wisdom.

Holy Rus #

Like a sponge absorbs water, newly converted Rus eagerly absorbed the Christian faith received from the Greeks. Our ancestors were diligent students and soon equaled their teachers in many ways.

The land of Rus was filled with numerous churches and monasteries, adorned with marvelous icons, and enriched with wise books. Our cities—Vladimir, Kiev, Novgorod the Great, Polotsk, Pskov, Rostov, Ryazan, Suzdal, Tver, Chernihiv, and Yaroslavl—shone with the splendor of the Church.

At that time, illiterate kings ruled in Europe, unable to sign their own decrees, while in Rus, the princes loved and respected books. In those days, church services in Europe were conducted in Latin, a language incomprehensible to the people, whereas in Rus, the Gospel was preached in the accessible Slavic language. In Europe, the Dark Ages of cruelty and superstition prevailed, while in Rus, magnificent churches were being built, akin to the beautiful Greek temples.

One notable advocate for Christian enlightenment and the wisdom of books was Yaroslav, the son of Prince Vladimir, who earned the title “the Wise” (he passed away in 1054). The chronicles say of him: “And under him, the Christian faith began to grow and spread. And Yaroslav loved books, reading them often, day and night. He gathered many scribes, and they translated from Greek into the Slavic language. And they wrote many books, with which faithful people instruct themselves and delight in divine teachings… And having written them, he placed them in the Church of Saint Sophia, which he had built himself. And he erected other churches throughout the cities and towns. Yaroslav rejoiced, seeing the multitude of churches and Christian people.”

Rus began to produce its own saints, who amazed the world with their love, humility, and piety. It became evident to the entire world that the Spirit of God had overshadowed our land, and the blessing of the Lord had descended upon our people. That is why our country has long been called Holy Rus.

The first Russian saints were the brothers Boris and Gleb, sons of Prince Vladimir. In 1015, they were murdered by the followers of Prince Svyatopolk, who sought to seize the throne of Kiev. Refusing to fight for power, Boris and Gleb met their assassins with humility and prayer. From the blood of these passion-bearers, which soaked our land, countless hosts of new saints sprang forth.

In the middle of the 11th century, one of the first monasteries in Rus was founded in Kiev—the famous Pechersk Monastery with the Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos. It was established by the holy fathers Anthony and Theodosius, renowned for their strict monastic lives and piety.

The monks of this monastery were known for their asceticism and miracles. Many saints—both venerable ones and bishops—came from among the monastery brethren.

Now, from our own land, the Gospel message—the joyful news of the true God and the Son of God, Jesus Christ, who conquered death, trampled the devil, and saved humankind—was being spread. Russian missionaries carried this message to distant peoples who still lived in paganism.

In the 11th century, Bishop Leontius (who passed away around 1077) went from Kiev to the north of the Ancient Russian state, to the city of Rostov, bringing the teaching of the crucified and risen Christ. There he encountered stubborn, harsh, and wild pagans, from whom two of his predecessors had already been forced to flee.

The adult inhabitants of Rostov resisted Saint Leontius’ preaching and refused to accept baptism. Seeing their stubbornness, the bishop turned to the children with gentle, persuasive words. He gathered them in the church, taught them, and converted them to Christianity. Little by little, as the children were baptized, their parents followed. This is how the land of Rostov was baptized.

To the north, into the deep forests, the light of the Gospel truth was brought by a native of Rostov—Saint Stephen, Bishop of Perm (who passed away in 1396), who converted the Permians. As a young man, grieving over the ignorance of this people, he learned the Permian language and translated Christian books into it, for which he created a special alphabet. Arriving in this distant and harsh land, Stephen baptized the Permians and eradicated paganism.

In the 16th century, at the far northern edge, on the Kola Peninsula, where pagan Lapps lived along the shores of the cold sea, the monks Tryphon and Theodorite preached the Christian faith. They destroyed idols, scattered the priests, and proclaimed the Gospel to the Lapps in their native language, baptizing many people.

No misfortune or disaster could diminish the faith of our ancestors. Invaders attacked Rus—Pechenegs, Polovtsy, Mongols, Tatars, Lithuanians, Poles, Germans, and Swedes, all of whom sought to enslave her and destroy Orthodoxy—but our people stood firm. Their faith grew strong and was tempered, like steel forged in fire.

The holy prince Alexander Yaroslavich, known as Nevsky (who passed away in 1263), a faithful defender of the true faith, defeated the enemies of Rus more than once. On more than one occasion, the armies of arrogant German knights fled from his mighty sword. When the Germans could not conquer Rus by force, they resorted to trickery, sending envoys to the prince with a proposal to accept the Latin faith.

But Saint Alexander did not betray Orthodoxy and replied to the foreigners: — “We will not accept the faith from you!”

With prayer, Saint Prince Dovmont, baptized as Timothy (who passed away in 1299), also defeated the enemies. A Lithuanian by birth, he settled in the city of Pskov, where he was unanimously chosen as prince by the local people. He defeated the Germans and Lithuanians many times, rallying the people for battle with the victorious call: — “People of Pskov! Whoever among you is old is my father, and whoever is young is my brother. I have heard of your bravery throughout the lands. Now, brothers, it is time for us to face life or death. Let us stand for the Holy Trinity, for the holy churches, and for our Fatherland!”

With the blessing of Saint Sergius of Radonezh, Grand Prince Dmitry Ivanovich, known as Donskoy (who passed away in 1389), courageously went to the field of Kulikovo and, in a bloody battle, defeated the Mongol and Tatar hordes…

The Great Schism #

Over the course of two thousand years, the Church has endured more than one schism. Throughout the centuries, heretics repeatedly broke away from it, leading entire nations and countries in Asia and Africa astray. Even in ancient times, the Armenians, Egyptians, Syrians, and Ethiopians fell away from the Church, enticed by false teachings. But the greatest division was the Great Schism between the Eastern and Western Churches, which occurred in 1054, six hundred years before the Russian schism.

From time immemorial, differences in worship and church governance existed between Tsargrad and Rome. For example, the Greeks celebrated the liturgy with red wine and leavened wheat bread, while the Latins used white wine and unleavened bread—wafers baked from dough made solely of flour and water.

Furthermore, the Greeks did not hinder the nations who accepted Christianity from them from praying to God in their own languages. They encouraged the Gospel’s spread among these peoples, the creation of unique scripts for them, and the translation of church books into their languages. This was the case with our ancestors, the ancient Slavs. However, the Romans prayed in Latin, demanded the same from all Christian nations, and disapproved of translating the Bible and services into other languages.

Greek priests were allowed to marry before receiving holy orders, while the priests of the Western Church were required to observe celibacy. Additionally, Greek clergy and monks wore beards, while the Latins were clean-shaven.

The Greeks recognized only Church councils as the highest spiritual authority. The Latins, however, believed that the governance of the Church rested solely in the hands of the Patriarch of Rome—the Pope. They called him the Vicar of Christ, the successor of the Apostle Peter, and the supreme shepherd of the entire Church, over which he had full authority.

Over time, theological differences were added to these distinctions. However, the primary conflict revolved around the authority of the pope, which the Greek emperors and bishops did not acknowledge.

In 1048, Leo IX was elected Pope of Rome. At that time, Rome’s main enemies were the Normans—fearless seafarers from the north who struck terror across Europe with their raids. They had reached the Mediterranean Sea, captured the island of Sicily, and now threatened Italy and Rome.

The pope decided to seek assistance from the Greek emperor, Constantine IX Monomachos, and the Patriarch of Tsargrad, Michael.

Constantine was a careless and frivolous man. Therefore, the pope entered into correspondence with the patriarch. In his letters, Leo insisted on his primacy. He told Michael that the entire Eastern Church should obey and revere the Western Church as its mother. With this position, the pope justified the differences between the Latins and the Greeks.

The patriarch was willing to reconcile any differences but considered himself equal to the pope. Leo, however, refused to accept such equality.

In the early spring of 1054, a papal delegation arrived in Tsargrad, led by Bishop Humbert, a hot-tempered and arrogant man. The envoys were tasked with discussing the possibility of a military alliance between the Romans and the Greeks, as well as reconciling with the patriarch without diminishing the pope’s dignity.

However, from the very beginning, the Latins treated Michael without the proper respect, acting haughtily and coldly. When they met the patriarch, they did not bow or offer him the customary greetings. Seeing this behavior, Michael responded in kind—refusing to negotiate with them.

The Romans wanted to teach the disobedient Greeks a lesson, as a teacher would punish unruly students. They began staging theological disputes in the city, pointing out the differences in worship to the Greeks. Chief among their concerns was the question of which bread to use for the liturgy—leavened or unleavened. They also argued over whether bishops, priests, and monks should wear beards.

Meanwhile, Pope Leo died. When Humbert learned of this, he decided to return to Rome. But before leaving, he expressed his displeasure with the Greeks in an unusual way. On Saturday, July 15, 1054, during the patriarchal service, the papal envoys entered the Hagia Sophia, walked into the altar, and placed a bull of excommunication on the altar, condemning Michael and all who shared his views.

A dead silence fell over the church, which was filled with worshipers—everyone was stunned by what they saw. The Latins left the church, saying: — “Let God see and judge!”

The patriarch ordered the bull to be read. It declared: “Humbert, by the grace of God, bishop of the Roman Church, to all the children of the Church… By the authority of the Holy and Indivisible Trinity and the apostolic see, of which we are emissaries, and of all the Orthodox fathers who attended the seven Ecumenical Councils, we pronounce excommunication on Michael, which our lord the pope has decreed upon him and his accomplices unless they come to their senses. Anathema to Michael, who has misused the name of patriarch, and to all his adherents, together with all heretics, and along with the devil and his angels. Amen.”

Cries of outrage echoed through the church. The people supported the patriarch. A riot broke out, nearly costing the papal envoys their lives as they barely managed to flee Tsargrad. Five days later, Michael convened a council, during which the events were discussed and the Eastern Church’s response determined. It was decided to declare anathema on Humbert and the other envoys.

Thus began the Great Schism.

For the next century and a half, the Greeks and Romans made various attempts to negotiate reconciliation. The final division between the Eastern and Western Churches occurred after the sack of Tsargrad by the Latins in 1204.

That year, the Italians and French, who had long envied the glory, wealth, and beauty of the Greek capital, captured, plundered, and burned the great city. This was a devastating blow to the Greek Empire, from which it never recovered.

Over the centuries of the schism, the Roman Church gradually drifted further away from Orthodoxy. New theological and liturgical differences emerged. Of course, the most significant change was the alteration of the rite of baptism by the Latins.

The ancient Church knew only one way of performing baptism: by triple full immersion in water with the invocation of the names of the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This was how baptism was performed since the time of the apostles. This was how the Greek Church baptized, and following it, so did the Russian Church.

However, the Latins began to baptize not by immersion, but by pouring or sprinkling water. The Eastern Church does not recognize such a rite as valid. Therefore, from time immemorial, Latins who convert to Orthodoxy are baptized by triple immersion.

The Fall of Constantinople #

The Greeks called the capital of their country—the glorious Tsargrad—“New Rome” or “Second Rome,” reminding all nations that their state was the successor of the mighty Roman Empire, which once ruled half the world.

But as the centuries passed, the Greek state weakened and lost its former power. From the east, it was attacked by the Muslim Turks. Their countless armies captured and enslaved Greek lands and neighboring countries, including Slavic ones like Bulgaria and Serbia. By the 15th century, all that remained of the great Christian empire was its capital, surrounded on all sides by enemies.

The penultimate Greek emperor, John VIII Palaiologos, sought help against the Turks from the rulers of strong and wealthy Europe. The condition for this help was well-known: the Orthodox peoples had to submit to the Latins and recognize the Pope of Rome as the spiritual ruler of the entire Christian world.

After long negotiations, in 1439, in the Italian city of Florence, the Greek emperor and the Pope of Rome signed a union—an agreement for the unification of the Orthodox and Latins. It was also signed by Isidore, the Metropolitan of Moscow and the head of the Russian Church.

However, most of the Orthodox people did not agree to this betrayal of faith and rejected the union. The Grand Prince of Moscow, Vasily II, also rejected it. From then on, relations between the Russians and the Greeks began to cool. The fall of Tsargrad in 1453 was seen in Russia as divine punishment for the Greeks’ betrayal of Orthodoxy…

In 1451, a new ruler ascended the throne of the powerful Turkish state—Sultan Mehmed II—a cruel and treacherous man, devious and corrupt, who dreamed of capturing Tsargrad.

In 1452, the Turks openly began preparing for war against the Christians. The last Greek emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, a capable and wise man, hurried to gather all necessary resources for the defense of Tsargrad. Supplies and ammunition were brought into the city, and the walls and towers were quickly repaired.

Constantine understood that the Greeks would not be able to defend the city on their own. He pleaded for help from the rulers of Europe and the Pope of Rome. But no one came to his aid. In April 1453, a massive Turkish army surrounded Tsargrad by land and sea.

A long siege began. The Turks bombarded the city daily with cannons and launched repeated assaults. Yet the Christians skillfully defended themselves, repelling one attack after another. It was truly remarkable, as merchants, their servants, craftsmen, and even monks stood on the city walls alongside seasoned warriors.

Mehmed sent envoys to Constantine, declaring: — “The time has come to carry out what we have long planned in our hearts. What say you? Will you abandon the city and leave? Or do you wish to resist and, together with your life, lose your property, while your people, taken captive by the Turks, will be scattered across the earth?”

The emperor ordered a message to be sent to the sultan: — “To surrender the city is not within my power, nor the power of anyone else living here. By unanimous decision, we are all willing to die and will not spare our lives.”

Infuriated, Mehmed commanded the Turks to prepare for a final assault. More than one hundred thousand Muslims gathered beneath the walls of Tsargrad. They were opposed by fewer than five thousand Christians.

On the morning of May 28, 1453, Constantine gathered his commanders. He begged them not to allow the Muslim desecration of Christian holy places and to protect the women and children from falling into the hands of the Turks. He then went to the wounded and exhausted soldiers and bid each of them farewell. Many old warriors, who had seen much in life, could not hold back their tears.

In the evening, Constantine prayed in the great church of Tsargrad—Hagia Sophia—and then went to the palace, gathered his household, and said his goodbyes. All the city’s inhabitants did the same. Friends and strangers tearfully embraced on the streets. Women wept as they saw their fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons off to their final battle.

Shortly after midnight, a terrible screech and shouts were heard—the Turks launched their attack. Mehmed himself led them into battle. Trumpets blared, drums rattled, and cannons roared. But all this was drowned out by the deep tolling of the bells—the bells of the churches of Tsargrad sounded the alarm.

After a bloody battle, the Turks unexpectedly managed to capture part of the wall and raise their banner above it. The frightened Greeks began to retreat, and no one thought about continuing the defense. Only the brave Constantine continued to fight at the city gates. Surrounded by the Muslims, he cried out in despair: — “Is there no Christian here who will take off my head?”

A Turk ran up and struck the last Greek emperor from behind with a fatal blow of the sword.

The Muslims, consumed by their lust for plunder, violence, and bloodshed, stormed into the city. They broke into houses, capturing everyone inside. They only took the young as prisoners to sell into slavery, while the elderly were killed, and infants were thrown into the streets.

In terror, the townspeople fled to the church of Hagia Sophia. Soon, the enormous building was filled with refugees who prayed, hoping for miraculous salvation. But the Muslims reached the church, broke down its doors with axes, and began binding the Christians—men with ropes and women with their own headscarves.

After binding their captives, the Turks desecrated and looted the church: they hacked apart the holy icons, stealing the decorations from them, shattered and carried off the shining lamps, and plundered the golden and silver vessels used in worship.

The sight of Tsargrad was horrifying! The once impregnable walls and towers were destroyed, ancient churches and monasteries desecrated and looted, and the vast squares were filled with dead bodies. Christian blood flowed in streams through the streets. Women screamed. Children wept. Fires raged. And in the flickering light of the flames, the terrifying shadows of Muslims moved through the city, looting, enslaving, and killing.

By the evening of May 29, Sultan Mehmed arrived in the ravaged city. Riding a white horse, he entered the church of Hagia Sophia and stood still, amazed by its beauty. Immediately, the sultan ordered that the great church be converted into a mosque—an Islamic temple.

Thus, the power of the Greeks was extinguished forever. The Grand Duchy of Moscow remained the only free Orthodox state in the world. From the defeated Greeks, the sacred and grave responsibility to preserve the true faith passed to the Russian people.

To this day, this faith is passed down among our people from generation to generation with the utmost care, as a burning candle is passed from one person to another in the wind. May it never be extinguished!

The Baptism of Princess Olga #

(From the “Tale of Bygone Years”)

In the year 6463 (955), Olga went to the Greeks and came to Tsargrad. At that time, the emperor was Constantine, son of Leo, and Olga came before him. When the emperor saw her, he noticed that she was exceedingly beautiful and intelligent. He marveled at her wisdom during their conversations and said to her: — “You are worthy to rule in Tsargrad with us.”

But she, after thinking it over, said to the emperor: — “I am a pagan. If you want to baptize me, then baptize me yourself, otherwise, I will not be baptized.”

And so, the emperor baptized her together with the patriarch. After being enlightened by the sacrament, she rejoiced in both soul and body. The patriarch instructed her in the faith, saying to her: — “Blessed are you among the women of Rus, for you have loved the light and forsaken the darkness. The sons of Rus will bless you for generations to come, to the last of your grandchildren.”

He taught her about the church order, prayer, fasting, almsgiving, and bodily purity. She bowed her head, listening to his teaching like a sponge soaking up water. She bowed to the patriarch and said: — “By your prayers, master, may I be kept safe from the snares of the devil.”

She was given the Christian name Helen, like the ancient empress, the mother of Constantine the Great. The patriarch blessed her and sent her on her way.

After her baptism, the emperor summoned her and said: — “I want to take you as my wife.”

But she replied: — “How can you take me as your wife when you have baptized me and called me your daughter? And Christians have no such law—you know this yourself.”

And the emperor said: — “You have outwitted me, Olga!”

He gave her many gifts—gold, silver, silks, and various vessels—and sent her away, calling her his daughter. When she was ready to return home, she went to the patriarch to ask for his blessing for her journey. She said to him: — “My people and my son are pagans. May God protect me from all evil!”

And the patriarch said: — “Faithful child, you have been baptized into Christ and have put on Christ. Christ will protect you, just as He protected Enoch in the first generations, then Noah in the ark, Abraham from Abimelech, Lot from the Sodomites, Moses from Pharaoh, David from Saul, the three youths from the fiery furnace, and Daniel from the lions. So too will He deliver you from the devil and his snares.”

And the patriarch blessed her. She returned to her land in peace and came to Kiev.

Third Rome #

In 1472, Grand Prince Ivan III, the son of Vasily the Dark, married Princess Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Greek emperor, Constantine XI. Sophia arrived in Moscow from Italy, and along with her came the coat of arms of the Greek autocrats—the double-headed eagle. From then on, it became the symbol of the independence of Russian rulers. From that moment, Moscow began to be called the “Third Rome”—the successor of the great Tsargrad, the Greek state, and the Greek Church.

At that time, Christians would say: — “Ancient Rome fell due to impiety. The Second Rome fell due to the dominance of Muslims. The Third Rome is Moscow, and there will be no Fourth.”

It was also said of our Church: — “It is worthy to call it heaven on earth, shining like the great sun in the midst of the Russian land, adorned in every way with miracle-working icons and the relics of saints. And if God wished to dwell on earth, He would reside in it and nowhere else.”

And from 1547, the Grand Prince of Moscow began to be called Tsar—the autocratic ruler and defender of the Orthodox faith. The first Russian tsar was Ivan IV, known as the Terrible, the grandson of Ivan III and Sophia Palaiologina.

In 1551, under Ivan the Terrible and Saint Macarius, Metropolitan of Moscow and All Rus—a kind shepherd and a wise scholar—a great church council was held in Moscow. It became known as the Stoglav Council because its decisions were set forth in one hundred chapters.

This council adopted many important decrees aimed at promoting spiritual enlightenment, spreading books, flourishing church iconography, strengthening piety in the country, and eradicating poverty and vice.

In its concern for uniformity in church rites, the council confirmed and permanently established in the Russian Church those rites, customs, and ceremonies that we had inherited from the Greeks and carefully preserved for centuries, now known as the “Old Rites.”

By the blessing of Metropolitan Macarius, the printing of books began in Moscow. Until then, only handwritten books existed in Rus. They were few in number: a large book took a long time to copy and was very expensive.

But around 1553, the Gospel—the first Russian printed book—was published. In 1564, Deacon Ivan Fyodorov published the famous book Apostle. And in 1581, the Ostroh Bible, the first complete Bible in the Slavic language, was printed.

The widespread distribution of printed books strengthened the Church. However, while blessing the printing of books, Metropolitan Macarius also cared about spreading the Gospel to all peoples. In the 16th century, the Russian Church began preaching the Christian faith in the Volga region, the Ural Mountains, and Siberia—new lands that had been annexed to the Moscow Tsardom.

Rus grew and strengthened, and the Grand Prince of Moscow became the autocratic tsar, but the Metropolitan of Moscow was still considered subordinate to the Greek patriarch. This did not reflect the true state of affairs. Therefore, in 1589, the Patriarch of Tsargrad, Jeremiah, who had come to Moscow, elevated the Russian Metropolitan Job to the dignity of a patriarch.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Rus went through a terrible ordeal—the Time of Troubles. The invasion of the Poles, the rule of impostors, civil war, famine, and poverty did not break our people but instead solidified their faith in their special mission—to steadfastly and firmly uphold Orthodoxy.

In 1613, the Time of Troubles ended with the unanimous election of the young nobleman Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov to the Russian throne. Under him, the Moscow Tsardom became one of the most powerful states in the world. It seemed that it would remain the stronghold of the Christian faith forever.

And nothing foretold that soon, during the reign of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, the son of Mikhail Romanov, grave and irreversible changes would take place in Rus.

The Tsar and the Patriarch #

Just as unexpected clouds obscure the sunlight, so too do the malicious deeds of rulers darken and disturb great empires.

An unimaginable calamity befell our land in the middle of the 17th century. It did not come from foreigners, heretics, or rebels. The misfortune came from where it was least expected—from the Orthodox Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and his closest friend, the most holy Patriarch Nikon, the leader of the Russian Church.

Nikon was much older than the tsar. He was born in 1605 in the Volga region, in the village of Veldemanovo, and at baptism, he was named Nikita. His father was a poor Mordovian peasant. Nikita’s mother died early, and his father remarried a wicked and quarrelsome woman.

The stepmother despised Nikita. She often beat him and more than once tried to kill him. The harsh treatment and constant fear made the boy resentful and secretive. From a young age, the future patriarch harbored hatred toward the world and dreamed only of one thing: how to take revenge on his tormentors.

Stealing money from his father, Nikita fled to the Makaryev-Zheltovodsky Monastery. There he lived for some time, diligently reading books and intending to become a monk. But his father discovered his whereabouts and brought him home.

On the way back, Nikita encountered a Tatar soothsayer. After looking into a fortune-telling book, the Tatar said to the young man: — “You will be a great ruler of the Russian kingdom!”

And Nikita believed the prophecy. Secretly, the peasant’s son dreamed of becoming an all-powerful ruler, imagining how his enemies would fall at his feet and beg for mercy. But for now, the youth had to submit to the will of his elders—his father arranged for his marriage.

Nikita wanted to become a priest. Smart and determined, he achieved his goal—he was ordained a priest in a village church and later moved to Moscow.

All his children died in infancy. Mourning his offspring, the young priest and his wife decided to take monastic vows. After his wife’s tonsure, Nikita left the capital and traveled to the far north, to the Solovetsky Islands on the White Sea.

On Solovki, the priest settled in the secluded Anzersky hermitage, founded by the wise and visionary elder Eleazar. The hermitage was renowned for its strict rule and the austere life of its hermits. There, Nikita took the monastic vows and was given the name Nikon.

But soon a quarrel arose between Eleazar and Nikon, ending with the young monk fleeing Solovki. Afterward, the brothers of the hermitage often discussed a vision seen by Eleazar: one day, during prayer, he saw a huge black serpent coiled around Nikon’s neck, and in horror, he cried out: — “Russia has raised him to bring great evil upon herself!”

The fugitive arrived at the Kozheozersky Monastery and stayed there. In 1646, on matters concerning the monastery, he traveled to Moscow, where he met Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, who had just ascended the throne.

The tsar was young (born in 1629), inexperienced, and trusting. The monk from the distant monastery, tall, broad-shouldered, dignified, able to speak eloquently about salvation and interpret sacred texts skillfully, impressed Alexei Mikhailovich. The tsar kept Nikon in Moscow and drew him into his inner circle.

The son of a poor peasant became the tsar’s closest adviser and best friend. The tsar could not live a day without Nikon’s sweet conversations, nor could he take a step without his friendly counsel. In 1649, at the tsar’s behest, Nikon was consecrated as the Metropolitan of Great Novgorod. It became clear to everyone: soon, he would become patriarch.

In 1652, the most holy Joseph, Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus, passed away. The tsar appointed Nikon to his place. The Tatar’s prophecy had come true!

Now Alexei Mikhailovich himself called Nikon “father” and “great sovereign.” Unlimited power was placed in the hands of the new patriarch, but he used it for evil, feeding his vanity and pride.

Russian tsars and patriarchs were often visited by Greeks. Their lands had been ravaged by the Muslims, and their churches and monasteries were in distress. Therefore, Greek bishops and abbots traveled to Rus seeking alms. They brought with them holy relics and ancient icons, always receiving generous gifts in return—gold, silver, and furs.

However, the people of Moscow viewed the foreign guests with disapproval and mistrust. Greek piety differed greatly from Russian piety. The Greeks prayed quickly and briefly, did not make prostrations, crossed themselves carelessly, and even used three fingers to make the sign of the cross.

Meanwhile, the Greeks marveled at the widespread devotion in Rus. How strictly the church rules were observed here! No services were missed, nothing was distorted or shortened. How strict the fasting was! Even the tsar ate nothing but bread and water on fast days. How reverently the people stood in prayer! In the church, no one moved from their place or spoke; everyone stood still and silent, bowing together.

The Greeks marveled at the very piety and church beauty that had once astonished the envoys of Prince Vladimir. But in Greece, this holy ancient tradition had dwindled and faded due to the Turkish conquest, while in Rus, it had been preserved unchanged.

The Greeks often visited Alexei Mikhailovich and Nikon. Seeing that the tsar was young and fervent, and the patriarch proud and vain, they began to urge them to go to war with the Muslims and liberate Tsargrad. They told the tsar that if he liberated the city, he would become the ruler of all Orthodox peoples, and Nikon would become the Ecumenical Patriarch.

The Greeks said to the tsar: — “May the Holy Trinity grant you the throne of the great emperors! Free the Christian people from the hands of the infidels! Deliver us from captivity!”

The tsar took these flattering words as truth. With youthful zeal, he promised to sacrifice his army, treasury, and even his own blood for the liberation of Tsargrad.

While the cunning foreigners flattered Alexei Mikhailovich, Nikon prepared to become the spiritual ruler of the entire Orthodox world. He wanted to be no different from the Greeks and imitated them in everything. Nikon often sought advice from the foreign guests on what he could change to be more like them.

And they told Nikon that the Russian Church’s rites, customs, and ceremonies were different from those of the Greek Church. The Greeks had none of these. Therefore, the Russians must have invented them. Thus, Rus had strayed from the ancient faith, distorted it, and introduced innovations.

Then, after consulting with the tsar, the patriarch decided that the time had come to compare the ancient Russian books with the modern Greek ones.

The Beginning of the Schism #

At that time, the Greek Church was in a pitiful state. It was oppressed by the Turks and languished in ignorance. The traditions of piety had been forgotten. The education for which the Greeks were once renowned had disappeared. They had no printing presses of their own, so they had to rely on books printed in Western countries, by the Latins.

These books were filled with errors, inaccuracies, and deliberate distortions. And since the Greeks had no wise teachers, there was no one to point out these mistakes. The corrupted books spread to all the lands under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Tsargrad, including Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania, Moldavia, and to the Little Russians and Belarusians. These books introduced new rites and practices that contradicted the teachings of the Church and were foreign to the holy traditions. Here are some examples:

The most significant and noticeable change was in the sign of the cross. Whereas in ancient times it was made with two fingers (the index and middle), the Greeks now crossed themselves with three fingers (thumb, index, and middle). In the past, the liturgy was served with seven prosphora, but now the Greeks used five or even one. The seal on the top of the prosphora had also changed. In the past, it depicted an eight-pointed cross with the Gospel words “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world”. Now, the Greeks used a seal with a four-pointed cross and the inscription “IC XC NIKA”. In the past, during the reading of the Psalms, “alleluia” was said twice—“Alleluia, alleluia, glory to You, O God.” But now the Greeks said it three times—“Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia, glory to You, O God.” In the past, during the Lenten prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian, “O Lord and Master of my life,” full prostrations were made, but the Greeks had replaced them with bows from the waist. In the past, processions followed the sun (Christ), but now the Greeks walked counterclockwise. There were other differences as well. Over centuries of Turkish rule, the Greeks had lost the order and beauty of their services, allowing for reductions and changes, while the Russians had held firmly to the strict church service.

Our ancestors, who saw their country as the Third Rome and their Church as the last bastion of Orthodoxy, carefully preserved the ancient rites and customs, considering them an essential testament to the true faith, handed down by the apostles and taught by the holy fathers.

The Russians, strict defenders of piety and firm preservers of the old rituals, contrasted themselves with the Greeks, whose faith had become weak and diluted.

But Alexei Mikhailovich and Nikon dreamed of ruling over the entire Christian world. To unite the Orthodox peoples under Moscow’s rule, it was not only necessary to gather an army and declare war on the Turks but also to eliminate the differences between Russian and Greek rites.

Thus, at the beginning of the Great Lent in 1653, the tsar and patriarch began their church reforms. Nikon sent out a decree to the churches of Moscow introducing new rites: the Lenten full prostrations were abolished, and the faithful were ordered to make the sign of the cross with three fingers.

The first to receive the decree was Archpriest Ioann Neronov, who served in the Kazan Cathedral on Red Square. He was a respected priest, known for his piety and wisdom. After reading the decree, he was horrified and secluded himself for prayer. For a week, Ioann prayed without ceasing and heard a voice from the image of Christ: — “The time of suffering has come; you must endure it with unrelenting perseverance!”

From that moment on, the Russian Church entered a period of constant trial and unceasing struggle.

The patriarch’s decree upset many. Pious priests gathered in Moscow, pondering how to stop the tsar and patriarch and prevent the destruction of Russian Orthodoxy.

These priests, brave defenders of church tradition, wrote and presented a petition to Alexei Mikhailovich opposing the introduction of the new rites. The tsar immediately passed it on to Nikon. At the patriarch’s command, all who dared oppose him were swiftly arrested and exiled from Moscow.

Having silenced the opposition, Nikon felt emboldened and decided to convene a church council to continue the reforms. At Nikon’s suggestion, Alexei Mikhailovich convened a council in 1654 to review and abolish the Russian rites and customs that differed from contemporary Greek practices.

The council approved the “book revision”—the revision of Russian church books based on Greek models. However, scholars have long proven that the “revision” was not done according to ancient Greek and Slavic manuscripts but rather from contemporary books—dubious and corrupt, printed by the Latins.

Moreover, the “revision” was entrusted to unreliable and unscrupulous individuals, such as the Greek Arsenios—a traitor to Christ and a scoundrel who had spent many years imprisoned at the Solovetsky Monastery.

The only guidance for this “revision” was Nikon’s instruction to Arsenios: — “Print the books however you wish, as long as it’s not the old way.”

This senseless “revision” by the tsar and patriarch led to a centuries-long schism in the Russian Church and among the Russian people, dividing them into Old Believers (Old Ritualists, ancient Orthodox Christians) and New Ritualists (Nikonian followers).

In pursuit of these reckless reforms, the traditions of the ancestors were trampled upon, thousands of Christian lives were lost, and the Russian land was stained with the blood of new martyrs. Sadly, most of our people betrayed the faith of their fathers, were deceived, and followed Nikon. This tragic price was paid to achieve ritual unity with the Greeks.

Yet, Alexei Mikhailovich never sent troops to liberate Tsargrad. He never became the ruler of all Orthodox peoples, and Nikon never became the ecumenical patriarch.

Soon, Nikon quarreled with the tsar. Alexei Mikhailovich matured, gaining wisdom and strength, and became more independent. He began to resent the overbearing supervision of his friend, who interfered in all state affairs. Enraged, Nikon voluntarily left the patriarchal throne and departed from Moscow.

He believed the tsar would repent and call him back, but this never happened. The years-long quarrel between the tsar and the patriarch ended with Nikon being condemned, stripped of his rank, and sent into exile. Nikon outlived Alexei Mikhailovich by a few years and died in 1681.

Arseny Sukhanov #

Anton Sukhanov, the son of an impoverished nobleman, Putila Sukhanov, was intelligent and knowledgeable in the sciences and had a love for books. Everything he achieved in life was through his intellect. His intelligence brought him to Moscow and secured him a notable position in the Church.

In his youth, Sukhanov took monastic vows and was given the name Arseny. Once in the capital, he held important positions under the Moscow patriarchs. His knowledge of Greek and Latin made him indispensable for critical foreign missions. As a result, Russian authorities frequently entrusted Sukhanov with especially difficult assignments.

For example, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and Patriarch Joseph sent Elder Arseny to Patriarch Paisios of Jerusalem to study contemporary Greek liturgical practices.

In the spring of 1650, the elder visited the city of Targovishte, where Paisios often resided for long periods. Arseny spent several months there, engaging with the patriarch and his accompanying Greek clergymen—Archimandrite Philemon and Metropolitan Vlasios.

They often debated about matters of faith, especially the manner of folding the fingers for the sign of the cross.

Once, during a meal, Patriarch Paisios demonstrated the three-finger sign and asked Arseny: — “Is this how you Russians cross yourselves?”

In response, the elder showed the two-finger sign and said: — “This is how we cross ourselves.”

Paisios was outraged: — “Who instructed you to do it that way?”

And so began a debate about which custom was more correct and ancient, the Greek or the Russian. The patriarch was bewildered: — “Arseny, where did you get this practice? After all, you received Christianity from the Greeks.”

But the elder demanded an answer from the Greeks: — “Your Eminence, you became Christians before us, and we after. Tell me, where did you receive this practice, from whom, and in what time did you begin to cross yourselves with three fingers? And where is this written among you?”

Archimandrite Philemon replied for Paisios: — “It is written nowhere among us, but we ourselves adopted it from the beginning.”

Arseny triumphantly responded: — “You said well, that you yourselves adopted it from the beginning! And we also adopted it from the beginning. How then are you better than us? You received the faith from the apostles, and we from the Greeks, but from those who preserved the rules of the holy apostles and the Ecumenical Councils without blemish. You spoke the truth—that you yourselves adopted this practice, not according to the tradition of the holy fathers.”

— “Only in Moscow do you cross yourselves this way,” Archimandrite Philemon said, offended.

The Greeks then stood up from the table, upset that they had been unable to out-argue the Russian.

On another occasion, Metropolitan Vlasios said to Arseny: — “We cross ourselves with three fingers, and you with two. Both are correct. But we believe our method is better because we are older.”

— “I know, Your Eminence,” Sukhanov replied, “that you are older. But old clothing requires mending. If a stone chamber or church falls into disrepair, it needs to be fixed, and it will once again be new and strong. But you have allowed much to fall apart—the traditions of the apostles and the holy fathers. And you refuse to mend them, that is, to correct them. You puff yourselves up with pride and want to call yourselves the source of all faith.”

Upon returning to Moscow, Arseny detailed his debates with Paisios in his work Debate with the Greeks About the Faith.

Later, in 1653, by order of Alexei Mikhailovich and Nikon, the elder traveled to Mount Athos. He was tasked with bringing back ancient Greek and Slavic manuscripts needed for the preparation of new Russian liturgical books.

This journey required great caution, as Sukhanov carried with him a royal alms—funds and sable furs worth about 50,000 rubles—a fortune at the time!

Arseny safely arrived at Athos and distributed the generous alms. In return, the monks of Athos handed over 500 ancient books—Greek, Bulgarian, and Serbian. Sukhanov personally selected them from 18 monasteries.

The oldest manuscript Arseny brought back was a Greek Gospel over 1,050 years old, and many others were more than 700, 500, or 400 years old. Many of these ancient books were written on parchment—vellum, specially treated animal skin. Among the books Sukhanov acquired were even secular works (58 manuscripts).

From Athos, the elder went to Tsargrad to fulfill Nikon’s request for newly printed Greek books and cypress boards for icons. After traveling for two years, Arseny finally returned to Moscow.

However, the manuscripts acquired at such great effort and expense were not used in the publication of new Russian books. The individuals Nikon entrusted with the task lacked the knowledge necessary to work with ancient manuscripts. As a result, it was easier for them to rely on modern Greek and Western Russian—Little Russian and Belarusian—printed books.

Nevertheless, to give the new books an air of authority and respect, the patriarch ordered that they be labeled as corrected according to ancient manuscripts. For example, the preface to the liturgical book Sluzhebnik, published in 1655, stated: “This divine book has been corrected according to ancient Greek books from the Holy Mountain of Athos and parchment Slavic manuscripts.”

This was a lie, and it was obvious to everyone—not only the Old Believers but even the Nikonian followers.

At the end of the 17th century, the monk Sylvester Medvedev, who had once participated in the revision of church books, wrote: “Why has such division occurred in the Orthodox faith in the Moscow kingdom? Only because of the new Greek printed books, which do not align with the ancient Greek manuscripts. Everyone claims that the books have been corrected according to ancient Greek and Slavic parchment manuscripts. But not a single newly corrected book is entirely consistent with ancient Greek and Slavic parchment manuscripts. Every book disagrees with ancient manuscripts as well as with modern printed Slavic and Greek books. And the more they revise, the more changes they make according to their whims, and the more they confuse the Orthodox people.”

In the 19th century, scholars confirmed these words entirely.

Of course, Sukhanov knew this. But he did not participate in the debate between the Old Believers and the New Ritualists, nor did he expose Nikon’s lies. A peaceful life was more valuable to him than God’s truth.

Arseny continued to hold important church positions, living sometimes in the capital and sometimes in the Trinity Monastery near Moscow. It was there that he passed away in 1668.