Bishop Pavel #

The first Russian saint to suffer torture and death for his fidelity to ancient Orthodox piety and the old church rite was the holy martyr and confessor Pavel, Bishop of Kolomna and Kashira.

Unfortunately, little is known about him. We do not know the names of his parents. It is only known that his father was a priest. The exact date of Pavel’s birth is unclear, but it can be assumed that he was a contemporary of Patriarch Nikon, born in 1605. The future bishop was born in the village of Kolychevo, in the same Volga region where both Avvakum and Nikon were born. Their native villages were not far from each other.

Pavel’s father taught the young Nikita, the future Nikon, how to read. For a time, the peasant’s son even lived in the priest’s house. This is where the future bishop and future patriarch met as children. Perhaps those days spent in the priest’s home were the happiest of Nikon’s life.

The boys studied together, played together, swam together, and ran through the woods in search of mushrooms and berries. Who would have thought, watching these carefree children, that one would become the executioner and the other the victim?

For many years, the future bishop disappears from the record. We next encounter him at the famed Zheltovodsky Monastery on the banks of the Volga. Here, the priest’s son took monastic vows and was given the name Pavel. Here, he led a strict monastic life, engaging with the wisdom of the scriptures, and as an experienced ascetic, earned the honorable title of “elder.”

The Zheltovodsk Monastery was situated on a bustling trade route. Every year, a large market, attracting merchants from around the world, was held beneath its walls—the famous Makaryev Fair. By royal decree, the monastery received a portion of the profits from the fair, and it grew wealthy.

All the monastery’s finances were overseen by the treasurer. In 1636, Pavel became the monastery’s treasurer. A man of honesty and incorruptibility, he was respected and trusted by all.

When Nikon arrived in Moscow and gained favor with the tsar, he remembered his childhood friend. In the summer of 1651, Pavel was summoned to the capital and appointed abbot of the ancient Pafnutiev Borovsky Monastery.

After the death of Patriarch Joseph, a church council named twelve worthy men, one of whom was to ascend to the patriarchal throne. Among them were both Pavel and Nikon. But by the will of the tsar, Nikon became patriarch.

Nikon wanted those around him to be loyal and indebted to him. Thus, in the fall of 1652, he consecrated Pavel as bishop for the nearby towns of Kolomna and Kashira, believing he had found a loyal assistant and obedient supporter.

When the council was convened in 1654 to abolish the old Russian rites and introduce the new Greek ones, the patriarch never imagined that his friend would be the only bishop to dare openly oppose the church reforms.

At the council, Pavel declared: — “From the time we became Christians and received the true faith from our pious fathers and grandfathers, we have held to these rites and this faith, and now we refuse to accept a new faith!”

But these words were not heeded. The council approved the “book revision,” and all present signed the decision. The tsar and patriarch managed to persuade Pavel to sign the council’s resolution. However, the bishop later withdrew his signature.

Nikon, angered by the bishop’s defiance, summoned him and began to try to win him over through cunning. At first, the patriarch attempted to convince Pavel of the necessity of the “revision,” pointing to the “colloquial language” of Russian liturgical books. To this, the bishop responded that the truths of the Gospel and the apostles’ teachings were also written in simple language.

Then the patriarch pointed out the discrepancies between Greek books and practices and those of the Russian Church. To this, the bishop replied that while the new Greek rites differed from theirs, the ancient Greek rites fully aligned with Russian church tradition.

Pavel’s steadfastness so infuriated Nikon that he shouted in a terrifying voice, rushed at the bishop, tore off his monastic mantle, and mercilessly beat him. He continued to beat him until he himself was exhausted. The bishop fell, but upon regaining consciousness, he rose, meekly thanked the patriarch, and stood in silence.

Afterward, Nikon ordered his servants to chain Pavel, take him to prison, and keep him under strict guard. Yet, the bishop did not despair or complain about his fate. Instead, he prayed and thanked God for the honor of suffering for the true faith.

The patriarch unlawfully stripped Pavel of his episcopal rank and exiled him to the ancient Khutynsky Monastery in Great Novgorod. The abbot of the monastery, eager to please Nikon, tormented the exiled bishop in various ways. For this, he was struck by divine punishment—he suddenly became mute and remained so until his death.

At the monastery, Pavel was deprived of contact with Christians. Nikon ordered that no one be allowed to see him, and those who insisted on visiting the deposed bishop were seized and imprisoned.

Then Pavel took upon himself the great feat of foolishness for Christ’s sake. To outsiders, it seemed as if he had lost his mind due to his sufferings, but this madness was feigned. Only by pretending to be insane could the bishop freely preach his fidelity to church tradition.

The abbot and the monastic brothers, believing Pavel to be mad, stopped bothering to monitor the “lunatic” and allowed him to wander the monastery grounds. The saint used this freedom to preach to the local people. He fatherly instructed the flock:

— “Beloved brothers and children! Stand firm in piety and hold fast to the traditions of the holy apostles and the holy fathers. Reject the innovations introduced by Nikon and his followers. Guard yourselves against those who cause strife and divisions. Follow the faith of the holy Russian shepherds, and do not turn to strange and foreign teachings. Honor the priest and remain under his guidance. Come to repentance, observe the fasts, avoid drunkenness, and do not deprive yourselves of the Body of Christ.”

When Nikon learned that the bishop was preaching loyalty to the ancient piety and teaching the people to adhere to the old rites, he decided to have Pavel killed. The patriarch sent his loyal servants to where the saint was preaching. The servants ambushed him in a desolate place and brutally murdered him. According to tradition, the martyrdom of Saint Pavel occurred on April 3, 1656, on Holy Thursday.

Protopope Avvakum #

The greatest defender of the old faith was the holy martyr and confessor, Archpriest Avvakum. He was born in 1620 in the village of Grigorovo , to the family of a priest named Peter. His fellow countrymen included Patriarch Nikon and Bishop Pavel.

Avvakum’s father died early, and his upbringing was left to his mother, a humble ascetic and woman of prayer. When Avvakum turned seventeen, his mother decided it was time for him to marry. The young man prayed to the Mother of God, asking for a wife who would be a helper in salvation.

Avvakum’s wife became the pious maiden Anastasia, the daughter of a blacksmith named Mark. She loved the priest’s son and prayed to marry him. Thus, through mutual prayers, they were united in marriage. Avvakum found in Anastasia a faithful companion who comforted and strengthened him during their most difficult trials.

The newlyweds moved from their native village to the nearby settlement of Lopatischi. According to the custom of that time, the son of a priest would inherit his father’s role, and at the age of 22, Avvakum was ordained a deacon. Two years later, he was ordained as a priest for the church of Lopatischi.

The young, zealous, and truth-loving priest drew the ire of the village authorities for standing up for the poor and downtrodden. Avvakum was beaten and driven out of the village.

With his wife and newborn son, the priest set out for Moscow to seek protection. The clergy in the capital warmly welcomed Avvakum, and Archpriest Ioann Neronov introduced him to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

Receiving a letter of protection from the Tsar, Avvakum returned to Lopatischi, but more troubles awaited him there. In 1652, he again journeyed to Moscow in search of justice. There, Avvakum was appointed Archpriest of the cathedral in the small town of Yuryevets . However, even here, persecution followed him. The local clergy, dissatisfied with the strictness of the new archpriest, incited the townspeople against him. Barely escaping death, Avvakum fled once again to Moscow.

In early Lent of 1653, when Patriarch Nikon sent out the decree introducing the new rites, Avvakum wrote a petition in defense of the ancient Church’s piety and submitted it to the Tsar. The petition ended up in Nikon’s hands, who ordered Avvakum to be imprisoned.

Nikon wanted to strip Avvakum of his priesthood, but the Tsar intervened on behalf of his acquaintance. Instead, the Patriarch exiled the priest and his family to Siberia, to the town of Tobolsk . In the autumn of 1653, Avvakum, along with his wife and children, set out on a grueling journey.

In Tobolsk, Avvakum continued to preach, condemning and denouncing Nikon. Soon after, an order came from Moscow: Avvakum and his family were to be sent to a stricter exile in the Yakutsk fortress. However, midway, a new order caught up with him—to join Voivode Pashkov’s expedition.

In the summer of 1656, Pashkov’s detachment set off. For Avvakum, this marked the beginning of the harshest trial he had yet faced: hunger, cold, unbearable labor, sickness, and the death of his children, all coupled with the Voivode’s cruelty.

In 1662, Avvakum was permitted to return from exile. For two years, the priest and his household made their way back to Moscow. Seeing that services were now being conducted according to the new books everywhere, Avvakum became deeply troubled. His zeal for the faith clashed with his responsibilities toward his wife and children. What should he do? Defend the old faith or abandon everything?

Anastasia Markovna, noticing her husband’s sorrow, grew worried:

— “Why are you so downcast?”

— “Wife, what should I do? The winter of heresy is upon us. Should I speak out or remain silent? You’ve all bound me!” the archpriest said in frustration.

But his wife encouraged him:

— “Lord, have mercy! What are you saying, Petrovich? I bless you, with our children, to continue preaching the word of God as before. Don’t worry about us. As long as God wills, we will live together, and when we are separated, don’t forget us in your prayers. Go, go to church, Petrovich, and denounce the heresy!”

Bolstered by the support of his beloved, Avvakum preached God’s word and condemned Nikon’s innovations in every city and village, church, and marketplace along the way to Moscow.

By the spring of 1664, the exile had reached the capital. Soon, news of his return spread throughout the city, and the endurance of this righteous man, unbroken by the hardships of exile, and the greatness of his martyrdom earned him universal respect and admiration.

Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich personally received Archpriest Avvakum and spoke kind words to him. Taking advantage of this, Avvakum presented the Tsar with two petitions, in which he called on the Tsar to abandon Nikon’s new books and all his reforms.

The priest’s steadfastness began to irritate the Tsar. Before long, Avvakum was exiled again. This time, he and his family were taken north, to the distant Pustozersk fortress. However, on the way, Avvakum sent a letter to the Tsar, pleading for mercy for his children and asking for leniency in his punishment. The Tsar allowed Avvakum and his family to live in the larger village of Mezen, near the White Sea.

In the spring of 1666, Avvakum was taken to Moscow under guard to stand trial at a church council. The entire council attempted to persuade the archpriest to accept the new rituals and reconcile with their supporters, but Avvakum remained unwavering:

— “Even if God wills me to die, I will not unite with the apostates!”

After long disputes about the faith, Avvakum was shamefully defrocked. He, along with three zealous defenders of Orthodoxy (Priest Lazar, Deacon Feodor, and Monk Epiphanius), were sentenced to imprisonment in the Pustozersk fortress. In December 1667, these suffering followers of Christ arrived at their final earthly destination—a grim earthen prison.

Avvakum spent many years in this dark dungeon, yet his spirit did not falter. His sincere faith and constant prayer sustained him. In Pustozersk, in the cold pit, surrounded by complete darkness, with only the crimson, smoky light of a torch, Avvakum wrote numerous letters to Christians, petitions to the Tsar, and other works. Here, with the blessing of his spiritual father, Monk Epiphanius, the archpriest began his renowned “Life” (“Житие”).

Even now, through these writings, the voice of Saint Avvakum echoes loudly across all of Rus:

— “Stand firm, brothers, stand bravely, and do not betray the true faith. Though the Nikonites attempt to separate us from Christ through torment and suffering, how could they ever diminish Christ? Christ is our glory! Christ is our foundation! Christ is our refuge!”

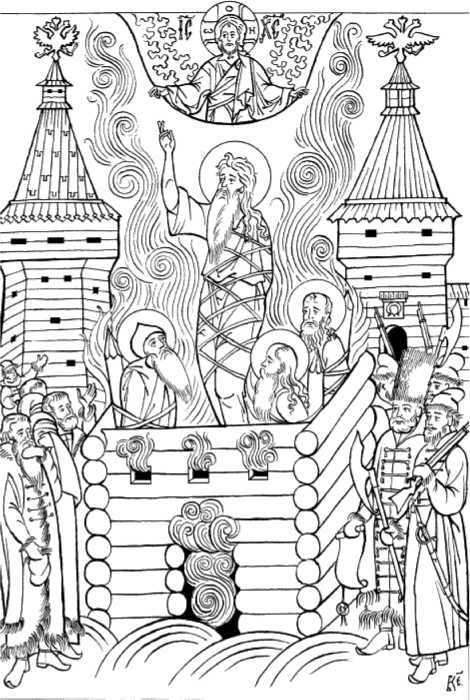

In 1681, Avvakum was accused of spreading writings against the Tsar and the higher clergy. A dire order arrived in Pustozersk: “For great slanders against the royal house,” Avvakum and his companions were to be burned in a log cabin. On Good Friday—April 14, 1682—Archpriest Avvakum, Priest Lazar, Deacon Feodor, and Monk Epiphanius were executed by being burned alive.

Protopope Daniil #

We call ancient Rus’ “Holy.” But of course, this does not mean that everything in it was holy, sinless, and without reproach. Humans live on the earth, not angels. And people are prone to flaws, offenses, and mistakes.

One of the main flaws of ancient Russian life, which has persisted to this day, was drunkenness. Since the time of Ivan the Terrible, taverns began to appear in cities and large villages—special houses where people gathered to drink and eat, to chat and have boisterous drinking sessions with songs and music.

Taverns generated great income. Therefore, during the reign of Alexei Mikhailovich, drinking establishments were transferred to the jurisdiction of the royal treasury. Now, the money spent by the people on vodka, wine, and beer flowed into the royal coffers.

Often, it wasn’t only townspeople and peasants who spent their last pennies in taverns, but also priests, deacons, and monks. For example, Father Peter, the father of Protopope Avvakum, was a frequent visitor to the tavern in the village of Grigorovo. He died early from drinking, leaving his wife with young children.

In drinking establishments, the people were entertained by skomorokhs—wandering singers and musicians. They played the gusli, tambourines, and flutes, danced, and sang humorous songs. The jesters traveled from town to town, village to village. They often brought along trained bears who could walk on their hind legs, dance, and bow.

On church holidays and during fairs, skomorokhs came to churches and marketplaces to entertain the crowd, wearing “hari”—as masks were called in olden times. But their jokes weren’t always harmless. Sometimes they were mockery and blasphemy.

The state and the Church fought against such folk entertainment. The Tsars and archbishops issued decrees banning jesting games and ordering the confiscation and burning of skomorokh masks, gusli, and flutes. However, only a few voivodes and priests dared to enforce these decrees, fearing the wrath of the crowd.

Avvakum, when jesters with bears came to his village of Lopatischi, drove them out. He smashed their masks and tambourines, and took two large bears. One bear he struck so hard that it barely survived, and the other he released into the field.

A bold fighter against immorality and drunkenness was Protopope Daniil, a friend of Avvakum.

Daniil served as a priest in Moscow. In 1649, he was appointed protopope of the Assumption Cathedral in Kostroma, which housed the wonder-working Theotokos Feodorovskaya icon—a venerated protector of the Romanov royal family and one of Rus’s greatest relics.

Daniil began his fight against the vices of the people, disregarding the opinion of the townsfolk. He actively opposed the skomorokhs, and in his sermons, he denounced the drunkenness of both laypeople and clergy. By his orders, disturbers of the peace, mainly drunks, were locked in the basement beneath the cathedral.

In 1652, during Maslenitsa and Great Lent, at Daniil’s insistence, all taverns in Kostroma were closed. This provoked the dissatisfaction of some townspeople and residents of nearby villages. Daniil’s boldness led to animosity against him from Kostroma’s voivode, Yuri Mikhailovich Aksakov.

Dissatisfaction and animosity soon grew into open hatred. Drunken peasants almost killed Daniil. This happened on May 25, 1652.

At night, drunkards were singing on the banks of the Volga. Daniil went to quiet them down, but they attacked him and beat him until he was unconscious.

Regaining consciousness, Daniil ran to the cathedral. But the peasants caught up with him near the voivode’s courtyard and beat him with clubs. Daniil shouted to the cathedral watchman to ring the bell and call for help.

However, neither the voivode nor the townspeople wanted to defend their cathedral’s protopope. A sleepy Aksakov came out but didn’t intervene on behalf of the priest. The peasants dispersed, leaving the bloodied Daniil behind.

Three days later, on May 28, a crowd of peasants from nearby villages appeared on the streets of Kostroma. The men marched with songs, shouting and laughing. Leading the crowd was a notorious troublemaking priest named Ivan, who led the peasants to free prisoners locked in the cathedral’s basement for various offenses.

The peasants broke the lock and released three drunkards from confinement. But they didn’t stop there. Threats against Daniil could be heard in the crowd.

Fearing for his life, Daniil first sought refuge in the cathedral, then hid for two days in a nearby monastery. The drunk peasants searched for him throughout the city. They found several people who had often been seen with Daniil and beat them.

The voivode didn’t interfere with the ongoing violence. Realizing that he couldn’t count on the authorities for protection, Daniil fled Kostroma for Moscow.

In the capital, he submitted a petition to the Tsar, describing his ordeals and painting a bleak picture of life in Kostroma: laypeople attending church services armed with knives, some insulting priests and threatening their lives, jesters singing songs outside the Assumption Cathedral, and Voivode Aksakov failing to assist the clergy while his men took bribes to release detained drunkards.

An investigation revealed how much the Kostroma townsfolk hated Daniil. Only a few of those questioned supported the protopope. Most claimed to have seen nothing, heard nothing, and knew nothing.

Daniil stayed in Moscow, living and serving in the Strastnoi Monastery beyond the Tver Gates. Unfortunately, this ancient monastery no longer exists. It was demolished in 1937. Now, Pushkin Square with its famous monument to the great poet stands in its place.

At the beginning of Great Lent in 1653, Daniil and Avvakum wrote and submitted a petition to Alexei Mikhailovich against Nikon’s new rituals. It was a detailed work compiled from church books about the two-fingered sign of the cross and Great Lent prostrations.

The Tsar handed the petition to the Patriarch, who ordered Daniil and Avvakum to be arrested.

Nikon defrocked Daniil and sent him to one of Moscow’s monasteries to bake bread. Daily work in a bakery by the hot ovens was considered a harsh punishment.

But Daniil did not submit, did not yield, and did not remain silent. He continued to denounce the Patriarch’s innovations. Then Nikon devised a harsher punishment for the protopope—exile to Astrakhan.

There, Daniil was kept in an earthen prison, tormented by hunger and thirst. Soon, the martyr passed away.

Monk Epiphaniy #

In Pustozersk, along with Protopope Avvakum, three more martyrs for the faith were imprisoned and then burned in a log cabin: Lazarus, a priest from the town of Romanov, Theodor, a deacon of the Kremlin’s Annunciation Cathedral, and Epiphaniy, a monk of the Solovetsky Monastery.

While sitting in the dreadful earthen prison, they did not lose hope or fall into despair, but tirelessly preached Orthodoxy—writing numerous works in its defense. Sympathetic streltsy (Russian military men) would smuggle their writings out to freedom.

From the distant Pustozersk, the writings of these martyrs spread across all of Rus’. They inspired the brave, encouraged the hesitant, and comforted the sorrowful.

At the request of Protopope Avvakum, monk Epiphaniy wrote his “Life” while in prison—a narrative of his own difficult life. However, in this work, the monk wrote not so much about himself as about the various miracles of God, of which he was a witness. Therefore, we know little about Epiphaniy’s personal life.

The future holy ascetic was born into a peasant family. After the death of his parents, he left his village and went to a large, bustling city where he lived for seven years.

In 1645, the young man arrived at the Solovetsky Monastery and stayed there as a novice. Seven years later, he was tonsured a monk and named Epiphaniy. After this, the monk lived in the monastery for another five years. They wanted to ordain him as a priest, but he humbly refused.

In 1657, liturgical books “corrected” by the Greek Arsenios, following the orders of Alexei Mikhailovich and Nikon, were brought to the Solovki. After examining these books, the monks grieved:

— “Brothers, brothers! Alas, alas! Woe, woe! The faith of Christ has fallen in the Russian land, just as it has in other lands at the hands of the two enemies of Christ—Nikon and Arsenios.”

Unwilling to pray according to the new ways, Epiphaniy, with the advice and blessing of his spiritual father, left Solovki. He took with him books and a copper-cast icon of the Theotokos.

The monk retreated to the remote hermitage of elder Kirill, who lived by the Suna River, flowing into Lake Onega.

Kirill, wanting to test the monk, blessed him to spend the night in a cell where a fierce demon had been living for some time.

In fear, Epiphaniy entered the dark, empty hut. He placed the cast icon of the Theotokos on the shelf, lit incense, censed the icon and the cell, prayed, lay down, and slept peacefully. The demon, frightened by the icon, fled the dwelling and did not return as long as the copper icon remained.

Kirill began to live in the same cell with Epiphaniy. They lived together for forty weeks, never seeing the demon either in dreams or reality. Later, Epiphaniy built a separate cell and moved the icon of the Theotokos there. The demon then returned to Kirill and began to torment him again.

On another occasion, when a fire broke out near Epiphaniy’s dwelling, the cast icon miraculously saved his cell from burning. The hut itself was charred, and everything around it was destroyed by the fire, but inside the cell, everything remained intact and unharmed.

While living in the wilderness, in 1665, Epiphaniy wrote a book denouncing Nikon and his innovations. The following year, the monk went to Moscow. At this time, a church council was in session. Fearless of punishment, the monk began publicly reading his book. He also presented a petition to the Tsar, asking him to reject Nikon’s innovations.

The bold monk was arrested and imprisoned. The council sentenced Epiphaniy, along with priest Lazarus, to punishment—having their tongues cut out and the fingers of their right hands severed, so they could no longer speak or write.

The execution took place on August 27, 1667, at Bolotnaya Square in Moscow, in front of a large crowd.

Lazarus and Epiphaniy bravely ascended the platform, where two chopping blocks and axes awaited.

First, the executioner cut out the priest’s tongue. At that moment, Lazarus had a vision of the prophet Elijah, who commanded him not to be afraid but to bear witness to the truth. The priest, spitting out blood, immediately began speaking clearly and purely, glorifying Christ.

Then Lazarus laid his hand on the block, and the executioner chopped it off at the wrist. The hand fell to the ground, miraculously forming the two-fingered sign of the cross.

Avvakum, who witnessed this, later wrote, “And the hand lay before the people for a long time. Poor thing, it continued to confess even after death, bearing unchanged the sign of the Savior. It’s a wonder to me: a lifeless hand rebukes the living!”

Epiphaniy begged the executioner not to cut out his tongue but to chop off his head right away. The executioner, flustered, replied:

— “Father, I will grant you peace, but what will happen to me? I am not allowed to do that.”

Then the monk made the sign of the cross and sighed:

— “Lord, do not abandon me, a sinner!”

He pulled his tongue out of his mouth with his hands, making it easier for the executioner to cut. Shaking from anxiety, the executioner barely managed to sever it with his knife.

Then they chopped off Epiphaniy’s hand. The executioner, feeling pity for the monk, wanted to cut it off at the joints so it would heal more quickly. But the monk signaled for him to cut across the bones. So, they chopped off four of his fingers.

The mutilated Epiphaniy was led back to the prison. Suffering from pain, he lay on a bench. Blood flowed from his wounds, and the monk prayed:

— “Lord, Lord! Take my soul! I cannot bear this bitter pain! Have mercy on me, a poor and sinful servant of Yours. Take my soul from my body!”

The monk prayed and wept for a long time, eventually falling into a deep sleep. Epiphaniy then had a vision of the Most Holy Theotokos. She came to him and gently touched his injured hand. The monk tried to grasp the hand of the Mother of God, but she vanished.

When the monk awoke, his hand no longer hurt. Over time, it healed completely. His severed tongue also began to regrow, and he eventually regained clear speech.

Later, the martyrs were sent to Pustozersk fortress. There, in 1670, Epiphaniy, along with Deacon Theodor, underwent another punishment—on April 14, their tongues were cut out again.

After this, the monk could no longer speak or even chew food. He began to pray:

— “Lord, give me a tongue, a poor man like me. For Your glory, for light, and for my salvation!”

He prayed for more than two weeks. One day, dozing off, he dreamed that he saw both of his severed tongues—the one cut out in Moscow and the one cut out in Pustozersk. The monk picked up the Pustozersk tongue and placed it in his mouth. It immediately attached itself back in place.

The monk awoke and wondered, “Lord! What will happen?”

From that moment, his tongue began to grow again and eventually returned to its original state.

In 1682, Epiphaniy was burned together with his fellow prisoners. After the fire died down, the executioners sifted through the ashes and found the bodies of Avvakum, Lazarus, and Theodor. Their bodies had not been consumed by the flames, but were only charred. However, the body of Saint Epiphaniy was not found. Many witnessed his ascent into heaven from the flames.

Archimandrite Spyridon #

Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and Patriarch Nikon entrusted the “correction” of our liturgical books to foreigners who had come to Moscow in search of honor, ranks, and wealth. At different times, various opportunists managed our church affairs: visiting Greeks and numerous Little Russians and Belarusians—natives of the western Russian Orthodox lands that had been captured by Poland.

The Latinized Poles oppressed the Russians, forbidding them from having schools and teachers. As a result, Orthodox Christians had to seek education in the schools of non-believers. To enroll in these institutions, they often had to temporarily, and at least outwardly, abandon Orthodoxy and adopt Latin Catholicism.

Little Russians and Belarusians were highly educated in the European style, with an excellent command of Latin and Polish. They could deliver ornate speeches, compose elaborate verses, and even read the stars. They imitated their Latin teachers in all things, while looking down on Russians with disdain.

They would say: “Is Orthodox Russia anything like the splendid Europe? There, life is carefree, morals are free, entertainment is abundant, and the clothing is beautiful, with magnificent palaces, delightful parks, loud music, lively dances, lavish feasts, and sweet wines. But in Russia, there is only prayer, fasting, the sound of church bells, bearded peasants, and women in headscarves…”

Patriarch Nikon claimed that our liturgical books contained many errors. Yet, he could not find a single misprint or mistake in them. However, Little Russians, Belarusians, and Greeks introduced numerous errors into the new books, filling them with heresy and temptation.

Sometimes, the “corrections” amounted only to swapping and rearranging individual words. Where the old books had “church,” the new ones corrected it to “temple.” Conversely, where “temple” had been, the new books printed “church.” “Youths” became “children,” and “children” became “youths.”

It was no wonder that the Old Believers were outraged:

— “Now there is not a single word left in all the books that hasn’t been changed or rearranged. And what is better in the new than the old?”

The dangers of Latin education and the wisdom of Europe were well known to Archimandrite Spyridon—a true defender of Christianity and a prolific church writer.

Semyon Ivanovich Potemkin, the future elder Spyridon, was born in Smolensk to a noble family. The Potemkin family’s history is tied to the western Russian lands and the city of Smolensk, which had been part of Poland since 1613.

Unfortunately, little is known about Semyon’s life before he became a monk. He was well-educated, had a wife, and children. In Smolensk, Potemkin frequently debated matters of faith with the Latin Catholics, defeating and humiliating them. As a result, non-believers respected him for his remarkable intellect.

Semyon received a Western education, attending a Polish school. He studied Greek, Latin, Polish, theology, and the art of oratory with great skill. From his youth, Potemkin shunned idleness and drunkenness, instead devoting himself to reading books, which remained his lifelong passion.

The Potemkin family belonged to the highest ranks of nobility and were related to several prominent families. Semyon’s sister was married to the influential courtier Mikhail Alekseyevich Rtishchev. Their son Feodor was a close friend and favorite of Alexei Mikhailovich, a supporter of Western scholarship, and an advocate of church reforms.

In 1654, the Russians recaptured Smolensk from the Poles. Soon after, Semyon was summoned to Moscow. It is likely that Tsar Alexei himself, who knew Potemkin well, invited him to teach at the school of the Andreev Monastery, founded by Feodor Rtishchev. In this school, invited Western Russian scholars taught Moscow’s youth Greek, Latin, and other European subjects.

In Moscow, Semyon took monastic vows and was renamed Spyridon. Nikon appointed him archimandrite of the Pokrovsky Monastery, founded in 1655 with funds from the Tsar. It can be confidently said that Potemkin enjoyed the favor of both the Tsar and the Patriarch.

However, in the matter of introducing new liturgical books and rituals, Spyridon opposed the authorities. He understood that these innovations had not appeared among the Greeks, Slavs, and eventually in Russia, without the influence of the Latins, Western education, and heretical texts.

The Archimandrite openly opposed the Patriarch’s reforms and wrote several works against them. After his passing, these writings were collected into a book by his disciple, Deacon Feodor.

Nonetheless, Alexei Mikhailovich held the wise Spyridon in such high esteem that he did not punish him for his dissent. Taking advantage of the Tsar’s favorable disposition, the archimandrite repeatedly asked him to convene a church council to condemn and overturn Nikon’s books and rituals.

The Tsar always responded kindly:

— “There will be a council, Father!”

But during Spyridon’s lifetime, the Tsar never convened one.

Respected by all, the Archimandrite lived to an honorable old age. The Tsar loved him so much that in 1662 he called him to be the Metropolitan of Great Novgorod. Feodor Rtishchev visited the elder and persuaded him:

— “Uncle, would you like to be the Metropolitan of Novgorod? The Church there is now widowed.”

The elder replied:

— “Feodor Mikhailovich, tell the Tsar I would rather go to the gallows with joy than become a metropolitan with the new books. What good will come of it? I do not wish to please mortal men.”

The Archimandrite did not live to see the gallows. He died at the end of November 1664. Soon after, a large council convened, which legitimized the persecution of the Old Believers. At this council, Feodor—Spyridon’s disciple, a deacon of the Kremlin’s Annunciation Cathedral, a famous writer, and defender of the Old Belief—was condemned.

Feodor often met and conversed with the elder. Under his influence, he began writing works against the church reforms. In December 1665, when the authorities learned of this, the deacon was arrested, defrocked, chained, and imprisoned. In August 1667, he was sentenced to have his tongue cut out and to be exiled to Pustozersk prison.

His tongue was cut out on February 25, 1668, in Bolotnaya Square. On the same day, he was taken to Pustozersk, where he would spend the rest of his days in an earthen prison. There, in 1670, he endured another punishment—on April 14, his tongue was cut out again, and his fingers on his right hand were severed.

Despite his mutilations, the martyr did not surrender, did not reconcile with the Nikonites, and continued to write works against them. For this, on April 14, 1682, Saint Feodor was burned in a log cabin along with Protopope Avvakum.

Boyarina Morozova #

In 1632, in Moscow, in the family of courtier Prokopy Fedorovich Sokovnin, a daughter named Feodosia was born. She grew up alongside two older brothers and a younger sister, Evdokia, in her father’s home.

At the age of seventeen, the modest and devout beauty Feodosia was married to Gleb Ivanovich Morozov, a senior boyar. Gleb was a severe widower, much older than his young wife—he was over fifty, renowned, and fabulously wealthy. Gleb loved Feodosia, and she returned his affection with respectful love.

In 1650, the Morozovs had a son, Ivan, a frail and quiet boy. Gleb Morozov passed away in 1662, leaving their young son as the sole heir to an immense fortune, under the guardianship of his mother.

In 1664, Archpriest Avvakum visited Morozova’s household after returning from his Siberian exile. Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich intended to settle Avvakum in the Kremlin, but the archpriest preferred the home of his spiritual daughter, the boyarina (noblewoman) Feodosia, over the royal chambers.

Avvakum guided Feodosia in piety, reading spiritually beneficial books to her in the evenings while she spun thread or sewed shirts. The threads, shirts, and money that Feodosia produced were given to the poor. She spent a third of the Morozov family fortune on the needy, while at home she dressed in patched clothing.

In her mansion, the devout noblewoman welcomed the sick, the blessed fools, and travelers. From them, she learned about Melania, a nun and disciple of Avvakum. Feodosia invited Melania to her home, housed her, and became her humble disciple.

At the same time, Feodosia desired to take monastic vows. She repeatedly pleaded with her mentor to tonsure her, but Melania did not rush the process. The secret tonsure finally took place in the autumn of 1670. Boyarina Feodosia Prokopievna became the nun Feodora.

Meanwhile, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, having been widowed, decided to remarry. The wedding banquet was to be held on January 22, 1671. Morozova, being the first court noblewoman, was invited. But by then, Boyarina Morozova was no more; there was only Nun Feodora. She declined the invitation, citing illness:

— “My legs hurt severely; I cannot walk or stand.”

The Tsar did not believe her and took the refusal as a grievous insult. From that moment, he harbored a deep hatred for the righteous woman and sought a way to punish her, while also seizing the vast Morozov estate for the treasury. When the Tsar learned that Feodosia adhered to the Old Belief, it became the pretext for her downfall.

In the beginning of the Nativity Fast in 1671, it became clear that Morozova was destined for imprisonment. One day, the Tsar discussed this with his close associates, including Prince Pyotr Semyonovich Urusov, the husband of Evdokia, Feodosia’s sister.

That same day, Urusov told his wife about the fate awaiting Morozova and allowed her to visit her sister for the last time. Evdokia stayed late at her sister’s home and spent the night.

Late at night, there was a knock at the gates, followed by shouting and barking. They had come for Morozova. Feodosia woke up in fear, but Evdokia reassured her:

— “Sister, take courage! Christ is with us—do not fear!”

The sisters prayed together and blessed each other to bear witness to the truth. Feodora hid Urusova in the pantry and lay down again.

Soon, without knocking or invitation, a royal envoy entered the sleeping quarters, accompanied by soldiers. He announced that he had come by order of the Tsar and forced the boyarina to stand for questioning. A search ensued, and the princess was found hiding in the pantry.

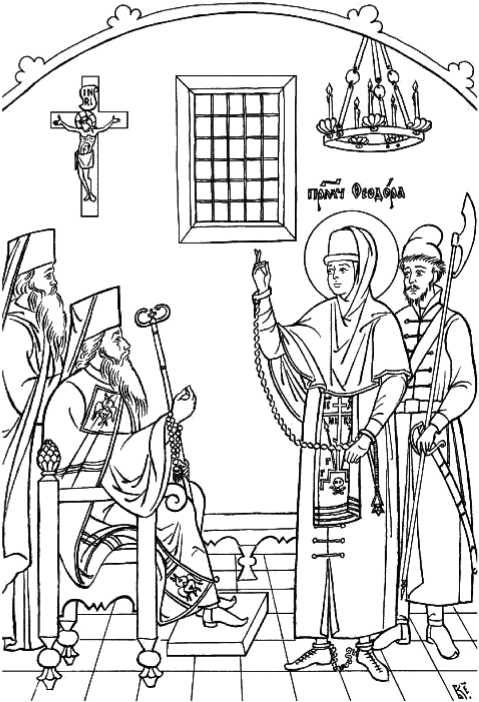

Feodora was asked:

— “How do you make the sign of the cross, and how do you pray?”

She demonstrated the two-fingered sign of the cross. Evdokia, being like her sister a spiritual daughter of Avvakum, did the same. That was enough. The sisters were shackled and locked in the basement, while the boyarina’s servants were ordered to keep strict watch over their mistress.

Two days later, the confessors were taken to the Kremlin for interrogation. Feodora remained steadfast.

Neither talk of obedience to the Tsar nor appeals to her son or household swayed her. She replied to the Nikonites:

— “You are all heretics, from the first to the last! Divide my words among yourselves!”

Evdokia was just as resolute. The sisters were shackled again and sent back to Morozova’s estate. Then they were separated and sent to different prisons.

During her long imprisonment, Morozova’s ailing son Ivan Glebovich died. Learning of her beloved son’s death, Feodora wept so bitterly that even the jailers shed tears of pity.

The Tsar, however, gloated over Ivan’s death. Now there was no one between him and the Morozov fortune, which immediately went into the treasury.

Yet, neither the death of her beloved son, the loss of her wealth, nor the torture and humiliation could shake Morozova’s faith. She remained firm and unyielding. Soon, she was sentenced to lifelong imprisonment in the fortress of Borovsk. Evdokia was sent there as well.

At first, the prisoners lived in relative freedom: they were fed, allowed to keep spare clothing, books, and icons. But everything changed when a new investigator arrived, who confiscated the meager belongings of the captives.

The sisters were transferred to a terrifying dungeon—a deep pit. The Tsar ordered that they be given no food or water. The two women, frail in body but strong in spirit, began to waste away. Evdokia was the first to die. Feodora survived her sister by only a short time.

Weakened from hunger and thirst, she called to the guard watching over the prison and tearfully begged:

— “Servant of Christ, do you still have a father and mother, or have they passed away? If they live, let us pray for them and for you. If they have died, let us commemorate them. Have mercy on me, servant of Christ, I am weak from hunger and need food. Have pity on me and give me a roll!”

— “No, my lady, I am afraid.”

— “Then some bread!”

— “I dare not.”

— “Well then, just a few crumbs!”

— “I cannot.”

— “If you cannot, then at least bring me an apple or a cucumber!”

— “I dare not,” the guard whispered.

The martyr sighed:

— “Very well, child. Blessed be our God, who has willed it so! If it is not possible, I ask you to grant me this last kindness—wrap my poor body in burlap and bury me beside my beloved sister.”

Sensing her death approaching, the nun again called for the guard:

— “Servant of Christ, I beg you, go to the river and wash my shirt. The Lord wishes to take me from this life, and it is not fitting for me to lie in the earth in dirty clothes.”

The guard took the shirt, hid it under the folds of his red caftan, went to the river, and washed it, weeping bitterly as he did so.

On the cold night of November 1st to 2nd, 1675, the holy Feodora died, passing from the stifling darkness of the bottomless pit into the unending light of the Heavenly Kingdom.

Job Lgovsky #

Among the holy ascetics venerated by the Russian Church, a special place belongs to Saint Job of Lgov. His faithfulness to Orthodoxy was not marked by the heroic feats of confession or martyrdom, but by monastic humility and a life of solitary asceticism.

The future ascetic was born in 1594 into a boyar family and was baptized with the name Ivan. His father, Timofey Ivanovich Likhachev, served successfully at the Tsar’s court.

Ivan, quick to learn, outpaced all his peers in literacy, astonishing his teachers with his intellect and diligence. Prayer and reading became the boy’s favorite activities. He began to ponder how to please God and save his soul. At the age of twelve, Ivan secretly left home, rejecting wealth and idleness. He joined wandering pilgrims, traveling across Russia and visiting many monasteries.

Young Ivan became particularly fond of the renowned Trinity Monastery of Saint Sergius of Radonezh. Here, he decided to stay and asked the abbot to accept him into the brotherhood. Seeing Ivan’s piety and virtue, the abbot agreed, growing fond of the boy as a son. Yielding to Ivan’s requests, he tonsured him a monk, giving him the name Job.

Job lived in the monastery for many years, but eventually sought permission to leave for a life of solitary prayer and silence. The abbot agreed and blessed his beloved disciple to seek out a remote, uninhabited place.

Wandering through desolate forests, Job finally found his desired refuge in the impenetrable woods and marshes of a place called Mogilevo, located on the picturesque banks of the Tsna River, which flows into Lake Mstino.

Here, Job lived in solitude, devoting himself to prayer and labor. However, a lost merchant stumbled upon his dwelling and tearfully begged the hermit for directions, promising in return to build a church on that spot in honor of the Mother of God.

The monk led the merchant out of the forest, and the latter fulfilled his promise, donating a significant sum of money for the church. Job began constructing a wooden church in honor of the Dormition of the Mother of God. Other monks seeking a solitary life started to gather around him, and soon a small monastery formed.

For the brotherhood, Job was a model of humility and obedience. On hot afternoons, he would tend the monastery’s livestock, allowing the shepherds to rest. He built cells for the monks with his own hands and even laid their stoves.

For his righteous life, the church authorities ordained Job as a priest. However, the brethren did not appreciate his ascetic labors. The monks scorned his patched clothing and despised his virtues. They believed the abbot was dooming them to starvation by giving away bread to the poor and needy. Not wishing to argue with the disgruntled monks, Job quietly left the monastery, taking neither food nor clothing.

After long wanderings, Job found another remote place called Rakova Pustyn. But even there, word of the righteous man spread, and more monks gathered, forming another monastery. As before, Job labored for the benefit of the brotherhood, chopping wood, grinding grain, hauling water, and washing clothes for the elderly monks.

Once, desiring to venerate the relics of the Moscow saints, Job made a pilgrimage to the capital. The patriarch Philaret heard of the renowned ascetic and desired to meet him. He invited Job to his residence and asked about his life. Philaret was so impressed by Job’s story that he blessed the hermit to stay in Moscow and serve as the patriarch’s cell attendant.

Job lived in the capital for some time, but, disliking worldly fame, he quietly left and returned to Mogilevo. The brotherhood, which had previously scorned him, reconciled with the elder. After living there for several more years, Job left the hermitage and set out in search of a new place for solitary life.

He found such a place on the Red Hills. But even here, Job could not hide from those seeking spiritual guidance. Once again, a new monastery formed.

When Patriarch Nikon began his church reforms, Job was among those who opposed the innovations. Life on the Red Hills became dangerous—Nikon was enforcing the new church rites with force across the land. Once again, the elder and his disciples went on their wanderings.

On the southern border of Russia, on the Lgov Hills, Job found a new place for solitary life. The monks dug caves in the hills, built cells, cleared forests, and planted fields. A small settlement of Old Believers fleeing government persecution grew near the monastery. A palisade with towers and embrasures protected both the monastery and settlement from the raids of steppe nomads.

These fortifications not only protected the monastery from infidel raids but also from the Tsar’s forces. In 1672, a detachment of streltsy (musketeers) was sent to the monastery to search for and arrest runaway Old Believers.

Though the monastery’s destruction was miraculously averted, Job realized it was no longer safe to stay. In 1674, he left the Lgov Hills and went to the Don River, where the free Cossacks, who steadfastly upheld the old faith, had long been inviting him.

Before leaving, Job visited Moscow one last time and met with the imprisoned nun Feodora, the exiled noblewoman Morozova. In the prison, Job gave communion to the suffering prisoner. The encounter moved the hermit so deeply that he could never recall her sufferings without tears for the rest of his life.

On the Chir River, a tributary of the Don, Job established his final monastery. Here, in 1681, he passed away. Sensing the approach of death, Job summoned the brotherhood and instructed them to open his grave after three years. If they found his body incorrupt, they would know that the old faith was pleasing to God and true.

All the Don region mourned the righteous man’s death. With tears, the brotherhood buried their elder in the monastery’s church. Soon, miracles began to occur at Job’s tomb. The sick were healed: the blind regained their sight, the deaf their hearing, and the mute their speech.

In 1689, steppe nomads attacked the monastery and burned it down. When the monks returned to the ashes, they were overjoyed to find that Job’s tomb remained intact. They opened the tomb and found the elder’s body and clothing completely preserved and miraculously fragrant, even though eight years had passed since his death.

The miraculous incorruption of Job’s holy relics filled the monks and Cossacks with joy. The seeds of faith and piety that Job of Lgov had sown bore good fruit in people’s hearts, and Orthodoxy was firmly established on the Don.

The Ruin of Solovetsky #

The Solovetsky Monastery is one of the most illustrious Russian monastic communities, founded in the 15th century by the venerable fathers Zosima and Savvaty on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea. Isolated and well-fortified, the monastery was occasionally used as a prison by the authorities.

From 1649, the Greek monk Arseny was imprisoned there. Having been educated in Italy, Arseny traveled extensively, living in various countries and changing faiths multiple times. He had been Orthodox, Catholic, and even Muslim at different points in his life.

Arseny came to Russia but was exposed as an apostate and exiled to Solovki. In 1652, the future Patriarch Nikon visited the monastery. Unfortunately, Nikon met Arseny, was captivated by his education, and brought him to Moscow.

When Nikon began implementing the new church rituals, he entrusted Arseny, the heretic, with the critical task of “correcting” Russian books according to contemporary Greek standards. However, Arseny had a poor command of both Russian and Church Slavonic, so his translations deviated significantly from the old texts. His work lacked clarity, precision, and contained ambiguous and misleading elements.

The “corrected” liturgical books were brought to Solovki in October 1657. The abbot of the monastery, the wise Archimandrite Ilya, ordered the books to be locked away and instructed the monks to continue using the old books. Before Easter of 1658, all the monastery priests signed a refusal to accept the new books. Shortly after, this refusal was ratified by a council of the monks and lay brothers.

In 1659, after the death of Ilya, the monastery was led by the elder Bartholomew. During his tenure, Nikanor, a monk of Solovki and former abbot of the Savvin Storozhevsky Monastery near Moscow, returned to the monastery for retirement.

In 1666–1667, a major council was held in Moscow, condemning the old church rituals and their adherents. Bartholomew and Nikanor were summoned to the council, where Bartholomew chose to renounce the old practices and submit to the authorities.

When the brotherhood of Solovki learned of this, they petitioned for a new abbot. As a result, the elder Joseph, who had also renounced the old faith at the council, was appointed as the new abbot.

Joseph arrived at Solovki, bringing barrels of wine, mead, and beer. However, the monks refused to accept him, declaring, “We do not need you as our archimandrite!” The monks smashed the barrels at the harbor and unanimously elected the honorable Nikanor as their abbot.

The monks and lay brothers sent petitions to Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich, reaffirming their steadfast rejection of the new books and rituals: “Command us, great sovereign, to continue serving in the Solovetsky Monastery according to the old tradition, as instructed by the wonderworkers Zosima and Savvaty, Philip and Herman. We cannot accept the new services, great sovereign.”

This was an open challenge to the authorities, and the response was swift: the Tsar sent streltsy (musketeers) to subdue the monastery. Thus began a prolonged siege of the monastery.

In 1673, the voivode Meshcherinov arrived at Solovki with orders to capture the monastery by any means necessary, under penalty of death. However, capturing the island monastery—Russia’s best fortress of the time—was no easy task.

Meshcherinov ultimately succeeded through treachery. The monk Feoktist, unable to endure the hardships of the siege, fled to the voivode’s camp and promised to lead the soldiers into the fortress.

On the night of January 22, 1676, under the cover of a snowstorm, a detachment infiltrated the monastery through a hidden passage. They killed the drowsy guards and opened the monastery gates. The voivode’s army stormed in.

A bloody battle ensued, brief and unequal. The Nikonian soldiers scattered throughout the fortress, breaking into cells and churches, killing anyone they encountered—armed or unarmed, young or old, monks or lay brothers. Satisfied with the massacre, Meshcherinov returned to camp.

The voivode ordered the lay brother Samuil Vasilyev, who had led the defense, to be brought to him for interrogation:

“Why did you resist the Tsar and repel the army from the walls?”

Samuil replied, “I did not resist the Tsar, but stood courageously for the faith of our fathers.”

Enraged, the voivode ordered Samuil to be beaten to death.

Next, the elderly Archimandrite Nikanor was brought before Meshcherinov. The aged and prayer-worn monk was unable to walk and was carried to the voivode on a small sled by the streltsy.

Meshcherinov asked, “Why did you resist the sovereign? Why did you not let the army into the monastery?”

Nikanor answered, “We did not resist the sovereign and never intended to. But we were right not to let you in.”

Infuriated by the elder’s bold response, Meshcherinov began to shout insults. Nikanor calmly replied, “Why do you boast and exalt yourself? I do not fear you, for I hold the soul of the sovereign in my hand!”

The voivode, seething with anger, leaped from his chair and began beating the elder with a stick. He struck him mercilessly on the head, shoulders, and back, and then ordered the saint to be dragged outside the monastery walls, thrown into the moat, and guarded until he died.

The soldiers laughed and jeered as they dragged the helpless elder by his legs, his head bouncing against the stones and earth. The bloodied martyr was thrown into the moat, where he perished from his wounds and the cold.

One by one, the remaining monks and lay brothers were brought before Meshcherinov. The interrogations grew shorter and shorter.

The Christians’ firmness and courage drove the voivode to order their execution without mercy: heads were chopped off, some were hanged by the neck, others by the feet, and still others were impaled on hooks. Out of the five hundred people under siege, only fourteen survived—the rest were killed.

The martyrs, led to their execution, cried out to the voivode, “The Tsar will soon follow after us! And you, tormentor, prepare yourself for God’s judgment with us!”

On January 22, 1676, Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich suddenly fell gravely ill. On the night of January 23, he had a terrifying vision: the elders of the Solovetsky Monastery appeared to him and began sawing his body into pieces. The martyrs’ prophecy was being fulfilled.

Sensing his impending death, the Tsar sent a swift messenger to Meshcherinov with orders to lift the siege. But it was too late. Halfway there, the Tsar’s messenger encountered Meshcherinov’s courier, rushing to Moscow with news of the monastery’s capture.

Alexey Mikhailovich died in agony on January 29. According to the Church calendar, this day was dedicated to the coming Second Judgment of Christ and His Final Judgment.

The Streltsy Uprising #

Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich was married twice. His first wife was Maria Ilyinichna from the ancient Miloslavsky family. She passed away in 1669. Two years later, the sovereign remarried, this time to Natalia Kirillovna from the relatively unknown Naryshkin family. From his first marriage, the Tsar had sons Fyodor and Ivan, and a daughter, Sophia. From his second marriage, he had a son, Peter.

After the death of Alexey Mikhailovich in 1676, Fyodor Alexeyevich ascended the throne. Without leaving an heir, he died in 1682, and immediately a power struggle ensued between the Miloslavsky and Naryshkin families.

The Miloslavsky faction wanted Ivan Alexeyevich to become Tsar, while the Naryshkins wanted the young Peter Alexeyevich on the throne. Meanwhile, Princess Sophia, a clever, ambitious, and power-hungry woman, had her own designs on ruling the country.

Crown Prince Ivan was a sickly and weak-willed young man, completely incapable of governing. Therefore, the boyars proclaimed young Peter, a strong and well-developed boy, as the new ruler.

Sophia realized that this meant she would face the usual fate of royal daughters—taking the veil and living out her days in a monastery. However, she was not willing to accept this and dreamed of power.

Determined to seize the throne, Sophia decided to incite an uprising among the Tsar’s army—the Streltsy (musketeers). They had long been discontented with their service, as their commanders, centurions, and colonels abused their positions: they severely punished the Streltsy, forced them to work for free on their estates, and often didn’t pay their wages for years.

Sophia’s loyalists stoked the army’s discontent by spreading rumors that under the Naryshkins, the Streltsy would face even more oppression and hardships. On May 15, 1682, a rumor spread through Moscow that the Naryshkins had murdered Crown Prince Ivan.

With the ringing of bells and the beating of drums, the Streltsy regiments, with banners and weapons, marched into the Kremlin. Shouting that they had come to root out traitors and murderers of the royal family, the soldiers stormed the palace. Although Crown Prince Ivan was alive and unharmed, the Streltsy began killing the Naryshkins and the boyars who supported them.

The army, supported by the townspeople, took control of the entire capital. The authorities had no choice but to listen to the demands of the rebels: they decreed that there would be two Tsars—Ivan and Peter—with Princess Sophia Alexeyevna as their co-regent.

The authorities agreed to these demands, and the dual coronation of Ivan and Peter was scheduled for June 25. The leader of the Streltsy was appointed Prince Ivan Andreyevich Khovansky, a renowned voivode (military commander) and a fervent Old Believer who did not hide his convictions.

During these turbulent times, many Christians thought that, taking advantage of the government’s weakness and Khovansky’s influence, they could convince Ivan and Peter to return to the old faith, which had been trampled under Alexey Mikhailovich and Nikon. The Streltsy and Muscovites drafted a petition to the Tsars, asking for the restoration of the true Orthodox faith throughout Russia and an open debate on the faith.

Prince Khovansky volunteered to mediate between the people and the royal court. On the day of the coronation, he presented the petition to Princess Sophia Alexeyevna and Patriarch Joachim. On June 27, Khovansky met with the patriarch, accompanied by representatives from the army and townspeople, to debate the faith.

This debate, held in private, led nowhere. Joachim was not inclined to engage in theological debate; he didn’t even have his own opinions on matters of faith. As he often said, “I know neither the old faith nor the new, but whatever the rulers command, that I will do and follow in all things.”

A second meeting was scheduled for July 5. That morning, crowds of Muscovites gathered in the Kremlin. In the Faceted Chamber appeared Tsarina Natalia Kirillovna, Princess Sophia, Patriarch Joachim, clergy, and boyars.

Carrying the cross, the Gospel, icons of the Mother of God and the Last Judgment, ancient books, and lit candles, the Old Believers entered the chamber, led by Father Nikita Dobrynin from Suzdal.

The famous “debate on the faith” began. Nikita read out questions to the Nikonians, but Joachim immediately told the group, “It is not for you to correct church matters. You must obey us. The new books have been corrected according to grammar, but you have not even touched upon the grammar and do not understand the power it holds.”

Nikita responded, “We did not come to discuss grammar with you, but the traditions of the Church!”

A heated discussion ensued. Joachim appeared uncertain, while Sophia encouraged him and passionately joined in the debate. The Old Believers read out their petition denouncing Patriarch Nikon’s innovations.

The Nikonians remained silent, unable to respond. Then Princess Sophia exclaimed, “If Patriarch Nikon is a heretic, then our father and brother are also heretics! Does that mean the current Tsars are not Tsars, and the Patriarchs are not Patriarchs? We will not listen to such blasphemy! We will all leave the kingdom!”

Laughter erupted in the chamber: “It’s about time you went to a monastery, Your Highness, and stopped disturbing the kingdom. As long as the Tsars are well, we won’t miss you!”

Angry, Sophia ordered the debate to end. It was decided that the discussion would continue on July 7. The Old Believers left the chamber triumphantly, shouting, “We’ve won! We’ve won! Believe as we do, people!”

But the debate never resumed. Sophia had bribed the Streltsy: centurions and colonels were given 50 to 100 rubles (a year’s salary), some were promoted, and the rank-and-file soldiers were given wine and vodka from the royal cellars. The army succumbed to temptation and declared their indifference to matters of faith: “We don’t care about the old faith. That’s the business of the Patriarch and the Church Council.”

The unfortunate soldiers, who had traded Orthodoxy for money and alcohol, seized the main defender of the Old Believers, Nikita Dobrynin, whom they had been ready to follow just the day before, and handed him over to the authorities. After brutal torture, the holy confessor was beheaded on Red Square on July 11.

Khovansky did not remain in power for long. Princess Sophia considered him too dangerous. The prince and his son were falsely accused of treason and plotting to overthrow the Tsars and seize the throne for themselves. Khovansky and his son were executed on September 17, 1682. The uprising, known as the “Khovanshchina,” bears his name.

This tragic uprising demonstrated to Christians that the authorities had irrevocably abandoned the old faith and had no intention of deviating from the path set by Alexey Mikhailovich and Nikon.

The Nun Devora #

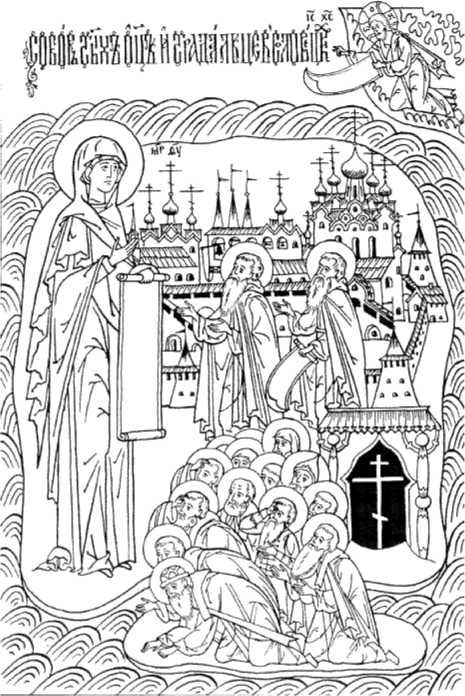

Among the holy men and women of the Old Testament, the prophetess Deborah stands out. This remarkable woman, who lived more than three thousand years ago during a time of great hardship for ancient Israel, inspired her people to rise up against a pagan king. Encouraged by Deborah’s prophecies and her presence on the battlefield, the Jews went to war and defeated the heathens. After the victory, the prophetess praised the Lord with a triumphant song:

“When the people of Israel take up arms, bless the Lord! Hear, O kings; listen, O rulers! I will sing to the Lord; I will praise the God of Israel… Thus let all Your enemies perish, O Lord! But let those who love You be like the sun, when it rises in its strength.”

The Jewish prophetess Deborah can be compared to the Russian nun Devora—noblewoman Evdokia Petrovna Naryshkina. This brave and inspiring woman courageously confessed her true faith, for which she suffered royal disfavor and disgrace. However, her name is less well-known than that of Lady Morozova.

Evdokia was the daughter of a nobleman, Pyotr Grigoryevich Khomutov. According to legend, the Khomutov family descended from a noble knight, Thomas of the Scottish Hamilton clan, who settled in Russia in the 16th century. The name “Hamilton” was modified into the more familiar “Khomutov.”

The Hamiltons were one of the most distinguished families of the Scottish kingdom and, at one point, even laid claim to its throne. They were frequently called upon to govern the country when the Scottish kings were minors. However, in Russia, the Khomutovs were counted among the lesser nobility.

Evdokia Petrovna married Fyodor Poluektovich Naryshkin, the brother of Kirill Poluektovich Naryshkin, who was the father of Tsarina Natalia Kirillovna. Thus, Evdokia was the aunt of Alexei Mikhailovich’s second wife.

Tsar Alexei’s marriage to Natalia Kirillovna raised the status of the Naryshkin family. In November 1673, Fyodor Poluektovich was appointed governor of Kholmogory.

Today, Kholmogory is a large village near the White Sea, but at that time, it was a prosperous city on a vital trade route—the only sea route through which Russia traded with Europe. In Kholmogory’s markets and warehouses, one could find an array of goods: honey, wax, caviar, copper, tin, lead, furs, perfumes, fine fabrics, and exotic spices.

Here, ships were built, rigging was made, and smithing, carpentry, spinning, and weaving trades flourished. Thus, the position of the Kholmogory governor was very significant, concentrating all civil, military, and judicial power along the White Sea coast.

While living in Kholmogory, the Naryshkin family became well aware of the siege and destruction of the Solovetsky Monastery, as it was from this city that the musketeer regiments departed to subdue the holy monastery.

However, this prestigious post brought little joy to Fyodor Poluektovich. He began settling into the city, building a stone palace and new wooden chambers at the governor’s estate. But the death of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1676 deeply troubled him.

Naryshkin feared that his family would fall out of favor with the new sovereign, Fyodor Alexeyevich. His worries and anxiety led to his death in Kholmogory on December 15 of that same year.

Evdokia was left a widow with three young sons—Andrei, Vasily, and Semyon. She took her husband’s body back to Moscow to bury him in the family crypt at the Vysokopetrovsky Monastery. After burying her husband, Evdokia stayed at the royal court.

Fyodor Alexeyevich’s suspicions were confirmed. The Naryshkins were not held in favor in the capital, and soon the widow experienced the Tsar’s wrath, which only intensified when it became known that Evdokia, like Lady Morozova, adhered to the Old Faith.

Just like Feodosia Prokopyevna, Evdokia Petrovna took monastic vows and became nun Devora. This was unheard of, scandalous, and unforgivable—the Tsarina’s aunt was a defender of the Old Belief!

For this, Naryshkina, along with her mother, children, and servants, was exiled to the distant village of Lobachevo in the Alatyr district. A special overseer was assigned to ensure that no one secretly visited her, brought her letters, or allowed her to communicate secretly or send letters of her own.

Perhaps the Tsar wanted to prevent Devora from communicating with her royal niece.

A guard of ten musketeers was placed around the exiled family, with shifts changing monthly.

However, Devora did not remain in Lobachevo for long. On July 29, 1678, she, along with her mother and sons, escaped from their guards and found refuge in the village of Pustyn in the neighboring Arzamas district.

Near this village, in a forest by the shores of Lake Pustyn, the nun built a small house. Though the trees completely concealed it from prying eyes, Devora dared not leave it during the day. She only ventured out at night to enjoy the view of the lake.

For six years, the local residents kept the hiding place of the royal relative a secret. But in 1684, someone informed the authorities about Devora’s shelter. Immediately, a royal decree was sent to Arzamas, instructing the local governor to send musketeers to capture the nun and imprison her.

Unfortunately, we do not know the details of how this order was carried out. However, it is certain that the nun was captured and sent to prison. Nonetheless, this did not affect the fate of her sons, who later served the Tsar. For example, in 1692, Semyon was appointed governor of the city of Solikamsk. Some sources suggest that Devora lived there until Semyon’s death in 1694.

In the village of Pustyn, Devora left a lasting memory. The place where her house stood became known as “Devora’s Place” or “The Tsarina’s Place.” In time, rumors spread that it had been the residence of Tsarina Natalia Kirillovna, who was exiled from Moscow for her loyalty to ancient traditions.

In the past, Christians gathered at Devora’s Place to pray together and read edifying spiritual books. In the mid-19th century, treasure hunters, taking advantage of the Old Believers, dug at this place and found a cauldron, a copper kettle, two silver spoons, and a prosphora seal.

That is all the material memory of Devora that the land preserved. But human memory proved more reliable. The Old Believers long revered the nun as a holy ascetic who loved the Lord and shone like the sun rising in its strength.