The Runaway Priesthood #

In the 18th and 19th centuries, priests who converted to Old Belief from the Synodal Church were called “runaway priests,” or “fugitive priests.” This was because they fled to the Old Believers from the Nikonians and were often on the run from the tsarist authorities.

The first Old Believer priest to receive ordination from a Nikonian bishop was the hieromonk Ioasaf, a beloved disciple of Job of Lgov.

As a child, Ioasaf followed Job in all his wanderings, moving with him from one monastery to another, including the Lgov Monastery, where Job tonsured Ioasaf.

Job saw the great need for devout priests among Christians, so he sent Ioasaf to his friend, Archbishop Ioasaf of Tver. This archbishop had been ordained by Patriarch Nikon in 1657 and served according to the new rites but secretly sympathized with the Old Believers. At Job’s request, Archbishop Ioasaf ordained Ioasaf the monk using the old service books.

Ioasaf returned to the Lgov Monastery, but in 1674, Job left the monastery and moved to the Don. Ioasaf, on the other hand, went to Poland, to the village of Vylevo, twenty versts from Vetka. Near the village, he built a cell and began living a life of seclusion, prayer, and fasting.

However, the local Old Believers were slow to accept Ioasaf as their spiritual guide. They considered it disgraceful that he had received ordination from a heretic. Some even harassed the meek elder, insulting and slandering him.

Discouraged, Ioasaf went to his spiritual mentor, Abbot Dosifey, who was then living on the Don. With sadness, Ioasaf shared his troubles and asked Dosifey to forbid him from serving if it caused a scandal among the people.

But the abbot recognized the great need for priests. He prayed and cast lots to discern God’s will. The lot fell that Ioasaf should continue serving.

Dosifey blessed Ioasaf and sent him back in peace. After traveling through many Russian and Ukrainian towns and villages, Ioasaf returned to Vetka and settled seven versts from Vylevo.

Eventually, the local people came to recognize the validity of Ioasaf’s priesthood. They invited him to move to the village and serve them. Being a kind and humble man, Ioasaf forgave their earlier rudeness and moved to Vylevo.

Meanwhile, Father Kozma had passed away, and with Easter approaching, the people of Vetka implored Ioasaf to come and lead the holiday service. Ioasaf agreed and soon moved permanently to Vetka.

In Vetka, Ioasaf decided to establish a church and a monastery. He persuaded the Old Believers to begin building a new church with an altar for the regular celebration of the Divine Liturgy.

However, according to church rules, such services required an antimins — a cloth consecrated by a bishop, with a depiction of the three-barred cross and a sewn-in relic of a saint. This symbolized the early Christians’ practice of celebrating the Liturgy on the tombs of martyrs.

Ioasaf had an old antimins, which had been brought to him by the nun Melania, a disciple of Protopope Avvakum and a mentor to the noblewoman Morozova.

Soon, a wooden church was built, and a monastery was established nearby. However, Ioasaf did not live to see the consecration of the church. He died in 1695, having lived in Vetka for five years, and was buried near the church. Twenty-two years later, his body and clothing were found incorrupt and intact.

Ioasaf’s relics were moved into the church, where a shrine was erected. An icon of Ioasaf was painted, and a service was composed in his honor, although both have been lost over time.

Following the example of the venerable Ioasaf, other priests, ordained by Nikonians, followed suit. The lives of these priests resembled those of the apostles.

To serve their many congregations, they had to travel secretly across Russia, visiting communities often located far from one another. Sometimes a priest would perform several weddings, baptize multiple infants, and conduct several funerals in one visit.

The need for clergy among Christians was constant and widespread. While there were millions of Old Believers, there were not even hundreds of Old Believer priests, only dozens. Thousands of devout believers would walk hundreds of versts to confess and receive Communion at churches where Old Believer priests served.

Some, due to the lack of priests, were forced to baptize their children themselves and enter unblessed marriages, receiving only the blessing of their parents. Many had the opportunity, only later in life, often in old age and already with children and grandchildren, to finally find a priest for a proper church wedding, sometimes just before death.

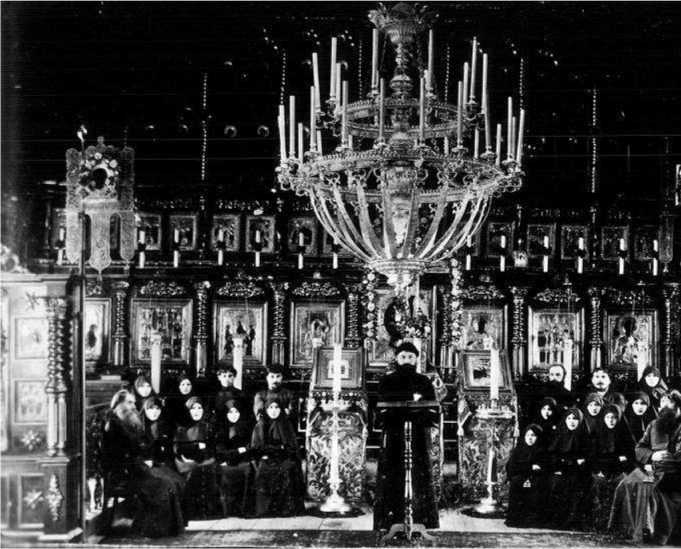

In those times of persecution, Old Believer liturgies resembled the liturgies of the first Christians in the catacombs of pagan Rome. When a priest arrived in a parish, whether in a town or a village, he conducted the service at night, in the home of a devout Old Believer, using a portable antimins and behind closed shutters.

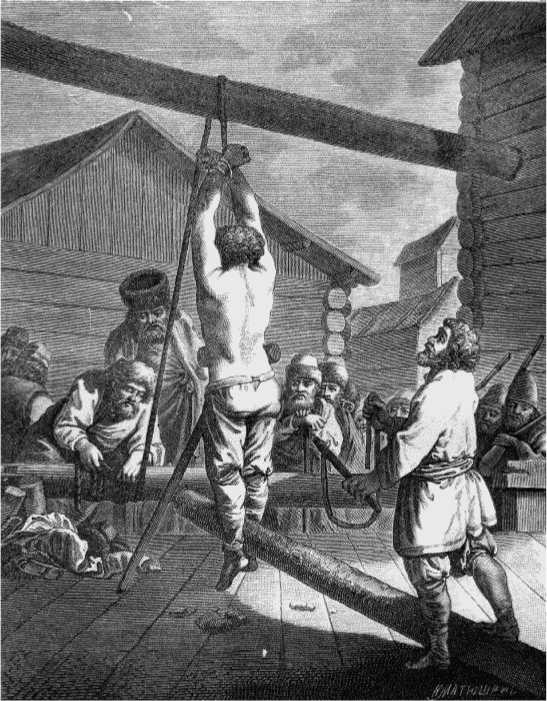

Priests were often captured and severely punished. The fate of a priest who fell into the hands of the authorities was grim. In the first half of the 18th century, a priest could be tortured, sent to a lifetime of hard labor, or imprisoned indefinitely.

One such example is the sentence handed down to Father Yakov Semenov by the Nikonian Archbishop in 1720: “He, the priest, during his time in Moscow, being in schism, acted according to the old printed books. And for this audacity of his, if no state crime pertains to him, he is to be punished and exiled to the Solovetsky Monastery, to a subterranean prison for repentance, where he shall remain until the end of his life.”

In other words, life imprisonment was prescribed simply for serving according to the old service books! Without a doubt, Father Yakov would have faced the underground prison, had he not died during the investigation. And Semenov was but one of thousands of martyrs who perished for the old faith.

The numerous settlements of the priestly Old Believers, their slobodas and villages, monasteries and hermitages, were not only in Vetka and Starodub. They existed throughout Russia — in Guslitsa near Moscow, on the Don, in the Volga region, the Urals, Siberia, and Altai.

In the 18th century, the most famous hermitages were in the forests of Nizhny Novgorod, on the Kergel River . Because of this river, Old Believers were often nicknamed “Kerzhaks,” a term still used colloquially today. During the reign of Empress Catherine II, many monasteries were founded on the Irgiz River , and the famed Rogozhskoye Cemetery in Moscow became a prominent center.

Konday Bukavin’s Appeal (From a letter to the Kuban Cossacks)

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on us. Amen.

From the young Don Cossack atamans, from Kondraty Afanasyevich Bulavin, and from the entire great Don Host, to the servants of God and seekers of the Lord’s name, the Kuban Cossacks, Ataman Savely Pafomovich, and all the brave atamans, we send greetings and a humble petition.

We beg for your mercy, brave atamans, and we beseech God while informing you that we have sent letters from our host to the Kuban regarding peace between us, that we may live in unity as our ancestors did.

Let it be known to you, brave atamans, about the actions of our previous leaders and their companions. In 1707, they corresponded with the boyars, suggesting that all Russian fugitives be sent away from the Don, back to where they had come from. Following their advice, the boyars sent Prince Yuri Dolgorukov with many high-ranking officials , intending to destroy the Don.

They began to shave beards and mustaches and to change the Christian faith, forcing the hermits who lived in the wilderness for the sake of God’s name to adopt the new Greek faith. As they traveled along the Don and other rivers, the prince and his companions began burning many Cossack villages and brutally beating the old Cossacks, cutting off their lips and noses, and hanging children from trees. They burned all the chapels and holy relics…

Now, our lords and fathers, Savely Pafomovich and all the brave atamans, we make a vow to God to stand for piety, for the House of the Holy Mother of God, for the Holy Catholic Apostolic Church, and for the traditions of the seven Ecumenical Councils, as the saints established the Christian faith in those councils and recorded in the books of our forefathers.

We have pledged our souls to one another, kissed the cross and the Holy Gospel, and vowed to stand united, dying for one another.

The Tara Uprising #

Like his father, Tsar Peter Alexeyevich was married twice. His first wife was Evdokia Fyodorovna from the ancient Lopukhin family. In 1690, their son Alexei, heir to the throne, was born.

However, Peter soon grew cold toward his wife. The fiery Peter did not like the quiet Evdokia, and he became bored with her. In 1698, the Tsar ordered her to be tonsured as a nun and confined to a monastery.

In 1703, Peter met the lowborn servant Marta Skavronskaya. She caught the Tsar’s eye, and he brought her close to him. Marta was given the Russian name Catherine, and in 1712, Peter married her. Empress Catherine gave birth to several children, whom Peter adored.

But Peter did not love his son Alexei. The boy grew up in Moscow without his father, surrounded by people devoted to the old ways — priests and monks — who instilled in him a disdain for his father’s reforms.

All the Russian people who longed for a return to the traditions of their ancestors, including the Old Believers, looked hopefully to Alexei. They believed that when he became the sovereign, he would restore the former Moscow kingdom.

Unfortunately, Alexei was never destined to rule. The years of animosity between father and son culminated in 1718, when Peter ordered Alexei to be arrested, tortured, and executed. However, Alexei died in prison before the execution could take place.

The death of the heir raised the question: who would rule Russia after Peter’s death? Would it be Tsarevich Peter, the son of Alexei and grandson of Peter? Or one of Peter and Catherine’s children?

The Tsar didn’t know how to resolve this. Thus, on February 5, 1722, he issued a decree stating that the reigning sovereign could name any successor of their choosing. All Russian subjects were immediately required to swear an oath of allegiance to this unnamed successor.

In early May 1722, the Tsar’s decree reached the town of Tara from Tobolsk, then the capital of Siberia.

Today, Tara is a small town on the banks of the Irtysh River. But back then, it was a Cossack fortress fortified with walls, ramparts, and towers. It stood on an important trade route to China.

Many Old Believers, both with priests and without, lived in and around Tara. Near the town were two large hermitages: one led by Father Sergey, a priest, and another by Ivan Smirnov, a priestless elder.

When the decree arrived in the fortress, rumors began to circulate that the unnamed successor to whom they were being asked to swear allegiance was the Antichrist. Father Sergey came to Tara and urged the people:

— You must not take the oath!

The people supported the hermit. Even the fortress commandant, Glebovsky, found ways to delay the day of the oath.

On May 17, a “contrary letter” — a written protest against the oath — appeared, written by Cossack Peter Baigachev. The letter stated that the people of Tara refused to swear allegiance to an unnamed heir of unknown lineage but would do so if given a named heir of the royal bloodline who upheld the traditions of the Old Orthodox Church. This letter was signed by 228 residents of Tara.

On May 18, in the house of Cossack Colonel Ivan Nemchinov, a disciple of Father Sergey, a large gathering began to discuss the “contrary letter.” Father Sergey’s followers, Baigachev and Cossack Ivan Podusha, read and interpreted the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers.

The people of Tara already had experience resisting Moscow’s authority. They had previously refused to obey the Tsar’s decrees on shaving beards and wearing German clothing, and nothing had happened to them. Now, the townspeople said:

— Before, we stood firm on the matter of beards and clothes, and no harm came to us. Now we’ll stand firm again. If they want us to swear an oath, let them give us a rightful heir to swear allegiance to.

Finally, May 27 arrived — the day Glebovsky had set for the oath. That morning, crowds of Cossacks and townspeople gathered at the town’s cathedral. The commandant was handed the “contrary letter.” He was taken aback and ordered it to be read aloud. Afterward, only a few swore the oath — some clergy and Glebovsky himself.

Soon after, some Old Believers, including Baigachev, fled from the fortress to Father Sergey’s hermitage. Meanwhile, the townspeople continued to hope for exemption from the oath.

But the Tsar sent a punitive detachment against the rebels — 600 soldiers and mounted Tatars with cannons. The force occupied Tara without resistance on June 14, and interrogations began immediately, leading to a long and brutal investigation.

Colonel Nemchinov, with 70 Cossacks, fortified himself in his own house. The attackers demanded their surrender. The besieged sent Podusha to negotiate, declaring that they refused to take the oath and would blow themselves up if assaulted.

Soldiers surrounded Nemchinov’s house on June 26. Negotiations continued, and many Cossacks wished to leave the siege. They were immediately captured. Twenty men remained with Nemchinov in the house. They set fire to barrels of gunpowder, and the house exploded.

The soldiers pulled the Cossacks from the fire. The most severely injured, including Nemchinov, were interrogated and soon died from their burns. The rest were healed only to be subjected to torturous executions. Nemchinov’s body was quartered.

Podusha, released the day before, barricaded himself in his own house with a dozen Cossacks. They held out in a siege until October, but he, too, eventually fell into the hands of the executioners.

In November, the punitive forces moved against the hermitages of Father Sergey and Ivan Smirnov, where many Old Believers had taken refuge. At Sergey’s hermitage, 170 priestly Old Believers were captured, along with a wealth of handwritten and printed books. Father Sergey was later quartered.

At Ivan Smirnov’s hermitage, the priestless Old Believers chose self-immolation when the soldiers approached.

Baigachev fled but was captured and imprisoned in Tobolsk. Fearing torture and execution, he bribed the soldiers guarding him, and they allowed him to take his own life along the way.

The leaders of the uprising were quartered, broken on the wheel, beheaded, impaled, and hanged. Common men were tortured on the rack and then flogged — receiving 100 lashes of the knout. Women received half as many — 50 lashes. Afterward, they were forced to swear the oath and were sent into lifelong exile.

In total, around 1,000 Christians were executed during the investigation, and many were exiled to hard labor. The Tara region was depopulated for many years.

Indeed, it is no wonder that the laws of the time declared the Old Believers to be “fierce enemies, continually harboring ill will toward the state and the sovereign.”

Varlaam Levin #

The audacious rumor that Peter I was not the true tsar but a cunning Antichrist spread across Russia. According to the laws of the time, such beliefs were considered an insult to the imperial majesty and were punishable by death. Among those who lost their heads over talk of the Antichrist was the monk Varlaam.

His secular name was Vasily Andreyevich Levin. He was born around 1681, the son of a landowner. Vasily spent his childhood on his family’s estate near Penza, in the village of Levino.

After learning to read and write, the young noble often engaged in conversations with the local priest, who was a devotee of the old church traditions. The priest himself made the sign of the cross with two fingers and taught Vasily to do the same.

The rumors of the Antichrist reached Levino as well. Vasily, with his fervent imagination, envisioned terrifying scenes of the end times: the reign of Satan, the persecution of Christians, and the tortures and executions to come.

In 1701, at his father’s command, Vasily joined the army. But he served reluctantly, and his regiment was stationed in Little Russia. After ten years, Levin was promoted to captain.

The thoughts of serving the Antichrist weighed heavily on Vasily’s conscience. He grew melancholy, sad, and eventually suffered from a mental breakdown, accompanied by epileptic seizures.

In 1715, while stationed with his regiment in the town of Nizhyn, Vasily conceived the idea of becoming a monk and fleeing far from the Antichrist. He requested permission from his general to leave the service and enter a monastery.

The general refused, for under Peter’s orders, soldiers and officers were forbidden from becoming monks. Disheartened, Levin went to church to attend a liturgy.

At the time, Metropolitan Stefan (Yavorsky), a well-known figure in the Synodal Church and a fierce opponent of the Old Believers, had arrived in Nizhyn from St. Petersburg. It so happened that Vasily attended the very church where the metropolitan was serving.

During the liturgy, the captain wept bitterly, attracting Stefan’s attention. After the service, the metropolitan invited Vasily to speak with him.

Levin shared his story with Stefan, recounting his time in the army, his illness, and his desire to become a monk, as well as his general’s refusal. Stefan advised him:

— They will not let you go. You are to be sent to St. Petersburg for evaluation. When you arrive, come straight to me before going to anyone else.

Four years later, Vasily’s seizures worsened, and his general sent him to St. Petersburg for medical examination.

Vasily was declared unfit for military service. He went to Stefan, who gave him a letter of permission for tonsure, addressed to the abbot of the Solovetsky Monastery.

However, Vasily did not travel to the distant monastery. Instead, he remained in the new capital.

Here, Levin met the spiritual father of Prince Menshikov, a priest named Nikifor Lebedka. This priest was a convinced, though secret, Old Believer. Vasily became his spiritual child.

One day, during confession, Vasily said to Nikifor:

— I cannot serve. The sovereign is cruel. And I recognize him as the Antichrist.

— Peter is the Antichrist. When I marry off my daughter, I will leave my wife and go to a monastery, — the priest replied.

Meanwhile, terrifying rumors spread through St. Petersburg. It was said that ships had arrived from overseas bearing the mark — the seal of the Antichrist. Everyone would be branded, and only those who accepted the mark would be given bread. The rest would starve.

Frightened, Levin left the capital and returned to his family estate, where his elder brother Gerasim lived. However, Vasily found no sympathy from his brother, who dismissed the rumors about Peter.

Back home, the retired captain began to preach his views. One day in December 1721, during a church service, he shouted to the congregation:

— Listen, Orthodox Christians! Hear me! The end of the world is near!

The priest rebuked Vasily:

— Why do you say such things? I will have your own peasants take you away.

But Levin persisted, shouting at the priest:

— They will shave your beards! You will be smoking tobacco! You’ll have two wives, three wives, however many you want!

Vasily’s behavior frightened his family, and they urged him to enter a monastery as soon as possible.

At the beginning of 1722, Vasily finally took monastic vows in a small monastery near Penza and was named Varlaam. However, his seizures continued. After one particularly severe episode, the monk decided to go to Penza and preach about the Antichrist.

Varlaam appeared in the town on market day. He climbed onto the flat roof of one of the meat stalls and shouted:

— Listen, Christians, listen! I served in the army for many years. My name is Levin. I lived in St. Petersburg. Peter Alexeyevich is not the tsar but the Antichrist. He will brand all men and women with his mark. Only those who bear the mark will receive bread. Those without the mark will be denied it. Fear these marks, Orthodox people. Flee, hide somewhere. The end is near! The Antichrist has come!

The crowd, terrified, scattered. This happened on March 19, 1722.

Varlaam returned to the monastery, but not for long. Soon after, soldiers came for him. The monk was arrested, taken to Penza, shackled in chains, and sent to Moscow. There, he faced harsh interrogations and brutal torture — the rack and the knout. But Varlaam held firm.

However, during the interrogations, he implicated dozens of others, including the influential Metropolitan Stefan and his own brother Gerasim. The monk did this deliberately, hoping that more people would suffer and receive martyrdom alongside him at the hands of the Antichrist.

Everyone whom the monk implicated was questioned. Most were acquitted, but some, like Nikifor Lebedka, were executed, accused only of honoring the holy faith of their ancestors.

When Varlaam realized he couldn’t escape execution, he grew frightened and began to recant his statements. He changed his testimony multiple times, at one point claiming to be an Old Believer and at another agreeing to be signed with three fingers.

In the end, the monk surrendered and asked for forgiveness from the emperor. But this did not save Varlaam. He was beheaded in Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square on July 26, 1722. Before the execution, his tongue was cut out.

Varlaam’s head was taken to Penza and placed on a stone pillar in the marketplace, where the monk had once tried to preach. His body was burned.

The Vyg Hermitage #

The hermitage founded in 1694 on the Vyg River with the blessing of Elder Korniliy holds a special place in the history of the Old Believers.

The first inhabitants of the Vyg Hermitage were actively engaged in spreading the doctrine of priestless Old Belief (bеспоповство), traveling throughout the Pomorye region, teaching:

— These present times are the times of the Antichrist! The Antichrist sits godlike on the throne within the Church.

As a result, word of the new settlement spread along the shores of the White Sea. Peasants, townsfolk, and even inhabitants from far-off places like Moscow and the Volga region began to relocate to Vyg.

Within just a few years, amid forests and swamps, a thriving hermitage emerged, with a well-organized economy: vast fields were plowed, vegetable gardens were tended, livestock was raised, and various industries—such as marine mammal hunting, small-scale manufacturing, and trade—were established.

The daily life of the Vyg inhabitants was governed by a strict monastic rule, modeled after the Solovetsky Monastery.

Initially, men and women lived together. However, in 1706, a separate women’s hermitage was built on the Leksa River, a tributary of the Vyg. The first abbess of this new convent was Solomoniya, the sister of Andrey and Semyon Denisov.

Andrey Denisov, who became the head of the Vyg Hermitage in 1702, was careful to maintain good relations with the authorities, which helped him advance the hermitage’s affairs in both Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

Denisov established connections with Tsar Peter I’s favorite, Prince Aleksandr Danilovich Menshikov, who was appeased with generous gifts. In September 1704, Menshikov signed a decree officially recognizing the right of the Vyg Old Believers to pray according to the old books. However, at the same time, they were required to submit to the administration of the Olonets mining factories.

These factories produced cast iron, steel, and copper, and manufactured weapons, including cannons, for the Russian army. The Old Believers were entrusted with the task of locating ores for the factories, a duty they performed successfully. For this reason, the factory administration held the Vyg community in high regard and protected them from harm.

Wishing to secure the favor of the highest authorities, the Old Believers presented gifts not only to Menshikov but also to the emperor himself, even though they considered him the Antichrist and did not pray for him. When Peter visited the Olonets factories, Andrey Denisov would send messengers to him with letters and tokens of goodwill.

The fall of Menshikov in 1727 deprived the Vyg Hermitage of a significant protector. Their relatively peaceful existence began to be overshadowed by frequent conflicts with both spiritual and secular authorities.

In 1738, following the denunciation by a former Old Believer, Ivan Krugly, another investigation of the hermitage was launched. Officials arrived at Vyg and accused the priestless Old Believers of not praying for the imperial authority.

The Old Believers were perplexed and unsure how to respond. Some were already preparing for self-immolation, but the more sensible brethren argued that there was no cause for such drastic action. Reason prevailed, and the priestless Old Believers agreed to pray for the tsars and tsarinas, whom they had previously called Antichrists.

In the second half of the 18th century, the Vyg Hermitage flourished. It had chapels, almshouses, granaries, various workshops, a pier, a tannery, and a copper-smelting factory where copper icons were cast. The nuns in the women’s hermitage engaged in spinning, weaving, and embroidering with gold and silver threads.

At the same time, there was a revival of spiritual life across Russia. Large priestless communities emerged in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, asserting their claims to leadership. Vyg, which had become dependent on wealthy merchants from the capital, found it increasingly difficult to maintain its dominance.

At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, a significant change occurred in the theology of the priestless Old Believers, comparable to the acceptance of prayer for the tsar — Pomorye accepted the doctrine of marriage.

The founders of the Vyg Hermitage had strictly adhered to the priestless doctrine of the advent of the Antichrist and the impending end of the world, which rendered family life unnecessary. The hermitage was established on strict monastic rules: all who came to Vyg took a vow of celibacy.

However, as the years passed and the prophesied end of the world did not arrive, absolute celibacy failed to take root in Pomorye, and the Old Believers began to form families, despite opposition from the abbots and mentors.

In 1762, Ivan Alekseyev, a priestless Old Believer, wrote an extensive treatise titled On the Sacrament of Marriage, in which he argued that marriage is not a church sacrament but rather a Christian folk custom.

Alekseyev’s teaching was supported and developed by Vasily Yemelyanov, a priestless mentor from Moscow. He believed that the power of marriage lay not in the wedding ceremony and prayers of a priest but in the mutual consent and promise of the bride and groom, declared before witnesses. Such a marriage could be blessed by a layman.

Yemelyanov was the first to independently officiate priestless marriages. In 1803, the Moscow mentor Gavriil Skachkov composed a special wedding rite with a solemn prayer service.

The new doctrine gained many adherents, prompting Yemelyanov to travel to Pomorye to seek support from the inhabitants of the Vyg Hermitage. At first, they refused to recognize the marriage doctrine and pressured the mentor to renounce it. However, in 1795, the inhabitants of Vyg relented and began to acknowledge marriages blessed by laypeople.

Today, Old Believers who recognize marriages performed without a priest form a distinct branch of the priestless movement known as the marital Pomorian concord.

The new teaching on marriage marked a departure from the previous doctrine of an imminent end of the world. From then on, the priestless preaching about the Antichrist and the last days sounded unconvincing and artificial.

However, the end times did arrive for the Vyg Hermitage itself.

In 1835, the authorities prohibited young people from living in the hermitage, removed the bells from the bell towers, and forbade the repair of old chapels and the construction of new ones. In 1843, Nikonian peasants were resettled on the Vyg lands.

In 1854, the authorities began demolishing the old structures—the fence, bell towers, and cemetery chapel. The following year, all the Old Believers were expelled from the hermitage, leaving only a few elderly, sick residents in the almshouses.

In 1856, the chapels of Vyg and Leksa, along with all their rich furnishings, were confiscated from the remaining few Old Believers and converted into parish churches of the Synodal Church.

Thus, after a century and a half of existence, the renowned Vyg Hermitage fell.

Feodosiy Vasilyev #

At the turn of the 17th–18th centuries, various preachers across Russia independently taught about the advent of the last days, the reign of the Antichrist, and the cessation of all church sacraments. In the regions around Veliky Novgorod and Pskov, this doctrine was preached by Feodosiy Vasilyev (1661–1711), the founder of one of the branches of priestless Old Believers — the Feodoseevtsy (Feodosian) concord.

Feodosiy came from a noble Moscow family, the Usovs, or Urusovs. His grandfather, Yevstraty, impoverished during the Time of Troubles and having lost all his relatives, moved from the capital to the village of Morozovichi near Veliky Novgorod. Feodosiy’s father, Vasily, served as a priest in the settlement of Krestetsky Yam .

After Vasily’s death, the parishioners petitioned the Novgorod Metropolitan Korniliy to ordain Feodosiy as a priest in his father’s place. However, Feodosiy was too young, and the metropolitan only ordained him as a deacon.

The young cleric initially showed himself to be a fervent supporter of church reforms and a persecutor of the Old Believers. However, under the influence of certain preachers, the deacon changed his views on Old Belief.

A zealous follower of Nikon’s reforms, Feodosiy Vasilyev became an equally zealous Old Believer. In 1690, he renounced his deaconship and, following the priestless doctrine, was re-baptized. Along with Feodosiy, his brothers, wife, son Yevstraty, and young daughter were also re-baptized.

Feodosiy and his family left the settlement and moved to a secluded location. There, he devoted himself to the diligent study of church books. His wife and daughter died in this period, and after burying them, Vasilyev fully dedicated himself to preaching the priestless doctrine. He traveled throughout the Novgorod and Pskov regions and even ventured into the lands of Latvia and Estonia, which at the time were divided between Poland and Sweden.

In 1694, already recognized as a preacher and teacher, Feodosiy participated in a council held in Veliky Novgorod. The council reaffirmed the necessity of re-baptizing all who wished to join the priestless Old Believers and required all adherents to lead a celibate life.

In 1697, the new Novgorod Metropolitan Iov, a persecutor of the Old Believers, ordered Feodosiy’s arrest. As a result, in 1699, Feodosiy and his followers were forced to flee to Poland. There, near the town of Nevel , two Old Believer monasteries were established according to a strict monastic rule: one for men, housing up to 600 people, and another for women, with up to 700 inhabitants.

Despite the persecution, Feodosiy frequently traveled back to Russia to preach among the townspeople and villagers. During these journeys, he met some of Peter I’s associates, including Alexander Danilovich Menshikov and other high-ranking courtiers.

In 1703, Feodosiy visited the Vyg Hermitage to engage in discussions with the priestless Old Believers there. These talks revealed certain differences in the teachings of the Feodoseevtsy and the Pomorian Old Believers.

For instance, one disagreement between the Feodoseevtsy and the Pomorians concerned the inscription on the titulus — the plaque placed above Christ’s cross. Feodosiy and his followers venerated the cross with the Gospel inscription: “Iсусъ Назарянинъ, царь iюдейскiи” (“Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”). Meanwhile, in Pomorye, they prayed before a cross inscribed with: “Iсусъ Христосъ, царь славы” (“Jesus Christ, King of Glory”), and they called the Feodoseevtsy’s inscription a Latin heresy.

Feodosiy’s first trip was peaceful, but by 1706, when he and his followers returned to Pomorye for further discussions on the titulus, the negotiations were far from amicable.

One Pomorian, Leontiy, pounded the table with his fists and shouted at the Feodoseevtsy:

“We don’t need your Jesus of Nazareth!”

Offended, Feodosiy left the Vyg Hermitage. In front of the entire community, he threw down the provisions they had given him for the journey and theatrically shook the dust from his feet. From then on, the Feodoseevtsy decided to maintain separation from the Pomorians in both prayer and communal meals.

In 1708, Feodosiy received permission from Menshikov to return to his homeland. Alexander Danilovich allowed the Old Believers to settle on his lands in the Pskov region. However, crop failures and disease decimated almost the entire community at the new settlement.

Thus, in 1710, the Old Believers received permission from Menshikov to relocate to another place — the Ryapina estate near the town of Yuryev. In May 1711, Feodosiy and his son set off for Veliky Novgorod to obtain a written permit for the ownership of the estate. However, while in Novgorod, Feodosiy was captured and handed over to Metropolitan Iov, who imprisoned him.

In the dark and damp dungeon, Feodosiy Vasilyev passed away on July 18, 1711. The metropolitan’s servants took the preacher’s body to a field and buried it. However, one of Feodosiy’s followers, Vasily Kononov, secretly observed where the burial took place. On the third night, he exhumed the remains, transported them far from the city, and reburied them by a small river.

But the Feodoseevtsy wanted to lay their revered teacher to rest at Ryapina estate. Thus, Vasily Kononov, along with another follower, traveled to Veliky Novgorod. On the Feast of the Sign of the Blessed Virgin, November 27, 1711, they unearthed Feodosiy’s remains again and transported them to the estate.

There, on the banks of the River Vybovka, the Feodoseevtsy solemnly buried their teacher with prayers and psalms. They planted a slender birch tree on the grave. Thus, the Old Believer community’s life at the new location began on a somber note.

The fertile land allowed the community to prosper quickly through farming and fishing. A mill and a blacksmith shop were built on the estate, and bells were acquired for the chapel. Local Estonians worked as hired laborers for the monastery’s enterprises.

However, the prosperity of the community was short-lived. After a false report from a soldier named Peter Tyukhov, claiming that runaway military servicemen were hiding there, an armed detachment was dispatched to the estate. Upon being warned of the approaching authorities, the residents scattered.

Although the accusation was unfounded, by 1722, the authorities had completely destroyed the community. The bells, books, and icons were handed over to a Nikonian church in Yuryev, and the chapel was converted into an Estonian church. The Old Believer community was left in ruins.

Nevertheless, Ryapina estate had served its purpose — from there, the teachings of Feodosiy Vasilyev spread not only across Russia but also into the lands of present-day Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, and Poland.

A hundred years ago, the celibate Feodoseevtsy concord was one of the most numerous branches within the priestless Old Believers. However, today, most of the Feodoseevtsy communities have joined the marriage-allowing Pomorian concord.

The Filippov Concord #

The Filippov Concord, which separated from the Pomorians, is closely related to the Feodoseev Concord in terms of its doctrine. This concord was founded by the monk Filipp (1674–1742), from whom it took its name.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Fotiy Vasilyev, a musketeer, left the Tsar’s service and moved to the Vygo Monastery. There, he took monastic vows and the name Filipp.

The first abbot of the Vygo Hermitage was Daniil Vikulin (1653–1733), one of its founders. In 1702, he retired, and Andrei Denisov became the new abbot. However, Daniil retained his duties as a spiritual guide. As a layman, he performed baptisms, rebaptisms, confessions, and conducted prayer services and burials.

In 1730, Andrei Denisov passed away unexpectedly. Filipp aspired to take his place, but the community elected Semen Denisov as the new abbot. Three years later, Daniil Vikulin died, and Filipp became the spiritual leader of the monastery.

Disagreements soon arose between Semen and Filipp. The monk wanted Denisov to consult him on all matters, which led the Vygo community to accuse Filipp of ambition.

In October 1737, a council was convened to address the discord between the abbot and the spiritual leader. The council exonerated Semen and condemned Filipp. Offended, the monk left the male monastery and moved to the women’s hermitage on the river Leksa.

The following year, the Pomorians were forced to begin praying for the Tsar’s authority. Such prayers also resounded in the chapels on the Leksa, and Filipp objected to this. Arguments erupted between the monk and the nuns during services, and Filipp, angered, struck his opponents with his prayer rope.

On the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross of the Lord, September 14, the monk could not bear it any longer. During the prayer service, he threw down the censer and ran out of the chapel, shouting, “The Christian faith has fallen!”

Leaving the monastery with his disciples, Filipp founded his own hermitage 30 versts away from the Vygo Hermitage, on the river Umba, which flows into the Leksa. Life in the new hermitage was difficult, marked by hunger and scarcity. The surrounding area was filled with forests, swamps, rocks, and moss. There was no fertile land nearby, so bread was always in short supply. Grain was purchased from the Vygo Hermitage, ground by hand, and mixed with crushed straw and pine bark.

Followers began to gather around Filipp — priestless Old Believers dissatisfied with the Vygo community’s submission to the Antichrist and prayers for him. Thus, a new branch of the priestless Old Believers emerged — the Filippov Concord.

At this time, the Vygo Hermitage was under investigation following a denunciation by Ivan Krugly. Government officials and investigators occupied the monastery. In October 1742, a new report was submitted: Elder Filipp and his followers were hiding from the authorities on the Umba.

An official, to whom the report was delivered, offered the priestless community a chance to hush up the matter for a bribe of five rubles. The Vygo monks informed Filipp, but he refused to pay. The report then gained public attention.

Investigators began inquiring about Filipp: “Who is he? How far does he live? How many people are with him?”

The Vygo monks denied everything: “We don’t know him, where he lives, whether it’s far or near. And we don’t know how many live with him. We haven’t been to him and don’t know the way.”

The investigators grew angry: “Is a place 30 versts away that distant, and you don’t know the road? Don’t worry, we’ll make you show us by force.”

Immediately, four soldiers, two officers, and two officials were dispatched to find Filipp’s hermitage. They were accompanied by a guide and ten local peasants.

A certain Vygo monk named Vasily, learning of the detachment’s departure, hurried to warn Filipp of the soldiers’ arrival. Upon receiving the news, Filipp instructed his followers to prepare for self-immolation.

The Filippovites locked the gates of the hermitage tightly, filled the well with logs and wood, and piled straw, resin, and birch bark inside the chapel.

Everyone — men, women, the elderly, and the young — gathered inside the chapel, locking the doors and blocking the windows with logs, leaving only a small window open. They waited for the soldiers to arrive.

After several days, the detachment reached the hermitage. The officers knocked on the gate. From the chapel, someone asked through the small window, “Who’s knocking?”

The visitors replied, “Guests have come for you. Open the gates!”

There was silence in the chapel. The officers then ordered the gates and doors to be broken down to capture the Old Believers alive.

As the doors were being hacked down with axes, the old women cried out, “Father, Father, they’re already breaking into the chapel!”

Someone said, “Bless us, Father, to light the fire!”

The dreadful words were repeated three times. Finally, Filipp responded, “God bless you, children!”

At once, the chapel was engulfed in flames. Amid the fire, the cries of the women could be heard, along with the monk’s final words, “Do not weep!”

A strong wind arose, blowing sparks and burning debris from the roof onto the soldiers and peasants, forcing them to retreat. They attempted to extinguish the flames, but the well was clogged.

Thus, Elder Filipp perished along with 70 Old Believers on October 14, 1742.

The fiery death of Filipp became an example for other followers of the Filippov Concord. Many of them followed their leader, preferring death by fire to life in the kingdom of the Antichrist.

The rejection of imperial authority was a foundational principle of the Filippov Concord’s doctrine. Later, other characteristics were added. The Filippovites did not recognize marriage or family life and strove to imitate monastic life in every way, for example, by refraining from eating meat.

This strict doctrine attracted many followers across Russia. The most significant Filippovite communities were in St. Petersburg, Uglich, and Kimry. Moscow had two Filippovite prayer houses — one in the Taganka district and another in the Balchug area.

In the Taganka district, on Durnoi Pereulok, was the so-called Brotherhood Court. For the Filippovites, it held the same importance as Rogozhskoye Cemetery for the Popovites or Preobrazhenskoye Cemetery for the Feodoseevites.

The Brotherhood Court was founded in the 1780s by settlers from Kimry. In 1789, a wooden prayer house was built, later replaced by a stone one. Also located in the Brotherhood Court were two almshouses, a garden, and two workshops that produced painted and cast icons.

In the early 20th century, a small bell tower was added to the prayer house. It was demolished by the Bolsheviks in 1926. In 1933, the Soviet authorities closed the prayer house. The old, low-slung building, with its thick walls and iron-barred windows, was only demolished in 1982.

The fate of the Brotherhood Court was shared by the rest of the Filippovite communities. By the 20th century, most of them had disappeared. Today, there are almost no Filippovites left.

On Feodor Tokmachev (from the “Russian Vineyard” by Semyon Denisov)

I will not omit the mention of the memorable man and patient sufferer, Feodor, known as Tokmachev, who came from a noble family in the Poshekhon village. For the sake of ancient church Orthodoxy, he abandoned his homeland and noble rank and wandered zealously through the Nizhny Novgorod wilderness.

He was a learned man, a lover of holy writings, from which he gathered a wealth of wisdom. In all things, he was a reasonable man, offering wise and remarkable words filled with great spiritual benefit…

However, this wise man was slandered, brought before archbishops in the capital city, and subjected to questioning in the ecclesiastical courts. Archbishops, judges, and noblemen all urged him to submit to the councils of Nikon, to join the new books, and to make the sign of the cross with three fingers.

To these questions, the wise man gave the following reasoned answer: “I think that if I make the sign of the cross with three fingers, the heavens will strike me with terrible thunder, the air will shake with dreadful whirlwinds, the earth will open up and swallow me alive as a daring criminal and cursed man.”

The enemies of ancient Orthodox truth could not bear these righteous words. Overcome with savage rage, they subjected him to the cruelest bloodshed and wounds. They did not spare his noble birth, nor were they shamed by the man’s wisdom.

Yet this wise man, enduring such suffering and wounds, showed no sign of cowardice or weakness. As a true man, he bore all things bravely: hanging on the rack, the breaking of his joints, the tearing of his flesh, and the shedding of his blood. He endured all with gratitude, courage, and patience, being ready not only to offer his body to wounds for the sake of piety but also to give his soul for the ancient Orthodox faith.

Seeing that neither their persuasion nor their tortures could defeat the man, the ecclesiastical judges condemned the wondrous sufferer to death by burning. He was placed in a cabin specially prepared and covered with straw and kindling. The glorious man was brought there, the cabin was set on fire, and there he was mercilessly burned.

Feodosiy of Vetka #

After the martyrdom of Saint Pavel of Kolomna, the Church was temporarily left without episcopal leadership. The highest spiritual authority passed to pious priests, learned monks, and virtuous laypeople. One of the wise steersmen, who skillfully guided the Church’s ship during those turbulent times, was the hieromonk Feodosiy.

He was ordained by Patriarch Iosif, the predecessor of Nikon, and served at the Church of Basil the Great in the Nikolsky Monastery of the town of Rylsk . At the beginning of the schism, unwilling to serve according to the new rites, Feodosiy left the monastery and settled in a wilderness by the Seversky Donets River.

Among the Cossacks, the elder was held in great esteem. Everyone listened to him and revered him for his kindness and wisdom. Many considered Feodosiy their spiritual father.

Before long, the elder was captured and brought before the local bishop, who tried to persuade Feodosiy to accept the reforms. After unsuccessful attempts, the elder was sent to Moscow to stand trial before Patriarch Ioakim. However, the patriarch also failed to force the hieromonk to accept the innovations.

Feodosiy was then handed over to secular authorities, who subjected him to torture and beatings after failing to sway him with words. But the righteous man did not waver. For his steadfast adherence to the faith, Feodosiy was imprisoned in the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery .

He remained in the dungeon for seven years. Pretending to have reconciled with the Nikonians, Feodosiy gained some freedom and immediately fled to Pomorye, and from there to Kerezhentsy. In 1690, he first settled in a hermitage by the Belbazh River and later in the Smolyan Hermitage.

At the Smolyan Hermitage, there were reserve Eucharistic Gifts for Communion. Christians from all over Russia would come to receive these holy Gifts. Using this opportunity, Feodosiy convened large church councils in Kerezhentsy to uphold Orthodoxy.

One of his faithful disciples and tireless assistants was Feodor Yakovlevich Tokmachev, a nobleman from Poshekhonye . However, Feodosiy and Feodor’s activities drew the attention of the authorities. In 1694, investigations began in Kerezhentsy. Tokmachev was captured and executed—burned in Nizhny Novgorod.

Feodosiy was forced to flee to Kaluga. There, the hieromonk found an abandoned Church of the Protection of the Theotokos. Due to its dilapidation, services had not been held there for many years, but the church had not been desecrated. It still retained an iconostasis from the time of Ivan the Terrible.

On Holy Thursday in 1695, Feodosiy celebrated the Divine Liturgy in this temple and consecrated a sufficient quantity of reserve Eucharistic Gifts. Their sanctity was unquestionable to all, for they had been consecrated in a pre-Nikonian church by a priest ordained before Nikon, following pre-Nikonian rites! Even the priestless Old Believers asked Feodosiy for Communion of the Body and Blood of Christ.

However, it was dangerous for the elder to remain in Russia with the Holy Gifts. Around this time, Venerable Ioasaf of Vetka passed away, and the Christians of Vetka sent the monk Nifont with a letter inviting Feodosiy to join them. In 1695, the hieromonk crossed the border and arrived at Vetka.

By that time, the population of the local settlements had grown significantly. The church that Ioasaf had begun building was too small to accommodate all the worshippers. Seeing this, Feodosiy ordered the church to be expanded in length and width and adorned with an ancient iconostasis, which had been transported from the abandoned temple in Kaluga. At the elder’s request, the Kaluga Old Believers sent the iconostasis to Vetka.

Recognizing the Church’s dire need for clergy, Father Feodosiy convened a council at Vetka, comprised of monks and laypeople. This council made a crucial decision for the future of the Church. It resolved to accept the ordination of clergy from the Nikonians. This decision saved the Church from being forced into a priestless existence.

The council decreed that clerics, monks, and laypeople from the new rite could be accepted into the Old Believers through confession, renunciation of heresy, and the sacrament of Chrismation. The Church follows this practice to this day.

However, to perform the sacrament of Chrismation, consecrated chrism was required—a fragrant mixture of olive oil, white wine, and aromatic herbs, symbolizing the grace of the Holy Spirit. Only a bishop, whom the Old Believers lacked, could prepare and consecrate the chrism.

The pre-Nikonian chrism was running out, and there was no place to obtain more. Therefore, following an ancient church rule, Feodosiy diluted the remaining old chrism with oil.

It was likely at this time that a rite of renunciation of heresy was composed for the Nikonians. Those converting to Old Belief would curse various innovations, such as the three-fingered sign of the cross, veneration of the four-pointed Latin cross, and the shaving and trimming of beards and mustaches.

The first clergymen received into the Church through Chrismation were Father Alexander of Rylsk, Feodosiy’s brother, and Father Grigory of Moscow.

Together with them, in the fall of 1695, Feodosiy consecrated the expanded Church of the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos. Thus, the first Old Believer church was established, where the Divine Liturgy was celebrated daily, sacraments were performed, and prayers were offered for the whole world.

From Vetka, reserve Eucharistic Gifts and chrism were sent throughout the Old Believer communities. Pilgrims flocked to Vetka in large numbers. Pious Christians generously donated to the Vetka monasteries and churches, offering bells, printed and handwritten books, priestly and deaconal vestments, icons in precious frames, and oil lamps.

Feodosiy passed away in old age in 1711. The Old Believers, mourning their beloved pastor, buried him by the altar of the Protection Church. Soon, people began to venerate him as a saint. A chapel was built over the elder’s grave, where people gathered for prayer.

In 1735, during the “Vetka Expulsion,” General Johann Weisbach, the commander of Little Russia, sent troops into the settlements. The faithful tried to save the relics of Venerable Fathers Ioasaf and Feodosiy. The latter’s body was found to be incorrupt.

However, the soldiers arrived before the Old Believers could act. They opened the tombs, examined the holy relics, placed them in new coffins, and sealed them with the military seal. By royal decree, the bodies of the saints were secretly burned by General Alexei Shakhovskoy on April 15, 1736.

Almighty God punished the impious persecutors of Christians. Weisbach died suddenly on August 24, 1735. Shakhovskoy passed away unexpectedly on May 27, 1736, from a severe fever.

Lavrenty of Vetka #

At the beginning of the 16th century, in the town of Kaluga, the holy fool Lavrenty performed acts of asceticism. According to tradition, he came from the noble family of the Khitrovo. An extraordinary man, Lavrenty lived mostly in the house of the local prince, Semyon Ivanovich. For his spiritual exercises, he would retreat to a secluded place atop a hill, where there stood a church and a small hut. Whether in summer or winter, the holy fool walked barefoot, wearing only a shirt and a sheepskin coat.

Later, a monastery was built at the place of Lavrenty’s ascetic struggle. In the early 18th century, the abbot of this monastery was Archimandrite Karion, a zealot of the true faith and ancient piety. He vehemently opposed the introduction of new rites in Kaluga, serving according to the old-printed books himself and not forbidding the local priests to do the same.

In the days of Hieromonk Feodosiy from Kaluga, a young man arrived at Vetka, probably a spiritual son and disciple of Karion. The young man was a relative of Blessed Lavrenty of Kaluga, perhaps a descendant of the Khitrovo family.

His secular name is unknown to us, but upon taking monastic vows at Vetka, he adopted the name Lavrenty in memory of his holy relative.

Monk Lavrenty spent many years in obedience at the Protection Monastery, which had been founded by Venerable Ioasaf at the Vetka church. Later, he left this monastery and established his own, dedicated to the Entry of the Most Holy Theotokos into the Temple. By the time of the “Vetka Expulsion,” Lavrenty had taken the schema—the highest degree of monasticism, the great angelic image.

In 1735, the elder avoided exile to Russia and, along with a few monks from the ravaged monasteries, retreated deep into the impenetrable wilderness by the fast-flowing Uza River. Here, twelve versts from Gomel, among dense forests, swamps, and bogs, Lavrenty built a small hut and a chapel dedicated to the Merciful Savior during the summer of that same year.

At that time, a punitive detachment was roaming the forests, searching for hidden Old Believers. But the Lord miraculously saved Lavrenty.

When soldiers surrounded his dwelling, the elder left his cell, approached a large oak tree nearby, and began to pray. He asked Almighty God and the Archangel Michael to hide him from the pursuers.

His prayer was answered. The soldiers did not see him. They passed by, finding no one, and left. Overjoyed, the elder thanked the Lord and Archangel Michael. He began to celebrate September 6th each year, marking his miraculous deliverance. This holiday later became a regular observance in the monastery of Venerable Lavrenty.

Christians seeking the eremitic life started to gather around the elder. Within a few years, a rather populated but extremely poor monastery emerged around his cell. During the first years of the monastery’s existence, the brothers often had to survive on oak bark and roots, not only as part of their voluntary ascetic effort but also due to poverty.

The monastery’s chapel had only four icons, which Lavrenty had brought from Kaluga: “The Miracle of the Archangel Michael in Colossae,” “The Entry of the Theotokos into the Temple,” “The Presentation of the Lord,” and “The Sign of the Theotokos.” These ancient icons were without any coverings or adornments. Only on major feasts were wax candles lit before them; during daily services, Lavrenty used a simple torch.

The elder established an extraordinarily strict rule in the monastery: if a monk sinned, he would first be admonished by the abbot and the council of brothers. Then he would be made to perform prostrations. If this did not help, the offender was chained in the basement. If even this punishment failed to correct him, the monk was expelled from the monastery in disgrace, forbidden to approach the monastery under threat of being beaten.

Lavrenty himself, a great prayerful and ascetic, set an example of ascetic life for the brothers.

The monks’ strict life and their unwavering observance of ancient piety inspired reverence among the people and earned the monastery great respect from local and distant Old Believers alike. By the mid-18th century, devout Christians from Moscow, Kaluga, the Don region, and other places began to send and bring monetary donations to Lavrenty’s monastery, along with gifts of liturgical books and icons, often richly adorned.

With the donations of pious benefactors, a magnificent four-tier iconostasis was constructed in the monastery chapel, unique in its adornments. The icons themselves were of ordinary craftsmanship, but each was adorned with gilded silver coverings.

Venerable Lavrenty passed away in 1776, having reached an advanced old age. When the brotherhood gathered around his deathbed, he blessed Monk Feofilakt to be the abbot after him and charged all the monks to strictly and diligently maintain the order he had established in the monastery and to forever preserve the harsh rule of ascetic life.

Then the elder spoke:

— Now, as I depart from this world, I can say with Symeon the God-Receiver: “Lord, now lettest Thou Thy servant depart in peace, for mine eyes have seen Thy salvation, which Thou hast prepared before the face of all people!”

The righteous servant of God was buried near the chapel. In the monastery treasury, the icons, his personal Psalter, and other liturgical books, which had belonged to the elder and were venerated as great relics, were carefully and respectfully preserved.

Thanks to the efforts of the subsequent abbots, the monastery was beautified and expanded. In its prime years, it had a church with six domes, a bell tower, a treasury, a refectory, a bakery, two barns, a large hay shed, a horse yard, 14 wooden cottages comprising 52 cells, and a blacksmith shop across the river. Almost every cottage had small gardens with fruit trees and sheds for firewood.

The monastery had vast forest lands, arable fields, and hay meadows. Among the monastic brothers were skilled icon painters, scribes, and bookbinders.

The Monastery of Venerable Lavrenty surpassed all other Old Believer monasteries in honor and importance. It was associated not only with the names of many venerable fathers but also with prominent church figures who worked gloriously for the benefit of Orthodoxy.

Having existed for over a hundred years, the Lavrenty Monastery was plundered by the authorities in 1839 and completely destroyed in 1844. It was thoroughly looted: the property was stolen, the buildings were demolished, and the bells and the magnificent iconostasis were handed over to one of the Nikonian churches. The monks were exiled, forbidden to wear monastic robes or preach the old faith.

Vikenty of Kroupsk #

The ancient hermits tormented their bodies, remaining silent for decades, lying in coffins, and living in foul caves, shackled to the darkest corners. They battled temptations, presenting the laity with a model of sinless living.

One of the forms of ascetic struggle was dwelling in caves—referred to as “pechery” in old times. The first Russian cave monastery was the Pechersk Monastery in Kyiv, founded by the Venerable Anthony (who passed away in 1073).

This elder, born in the town of Lyubech, took monastic vows on Mount Athos. In the middle of the 11th century, he returned to Kyiv, where he found a small cave on a secluded hill and began living there, devoting himself to prayer and fasting. All the while, he dug his cave continuously, never allowing himself rest by day or night.

The people of Kyiv soon learned of the righteous hermit, and devout people seeking a monastic life began to come to him. Anthony accepted them and tonsured them as monks. Thus, a small monastery formed. The brethren dug a new cave, with a church and cells inside.

Among Anthony’s disciples, the Venerable Theodosius (who passed away in 1074) was especially renowned. As a young man, Theodosius left his parents’ home and came to Anthony, fell to the ground, and with tears, begged for permission to stay. The elder pointed to his cave and said:

— Child, do you see this cave? It is a sorrowful place, worse than most others. You are young, and I doubt you can endure the sorrows of living here.

But the youth persisted, and the hermit allowed him to stay in the monastery. In the dark cave, Theodosius was tormented and tempted by invisible hordes of demons.

After evening prayers, the monk would sit on a chair to nap, always sleeping upright, not allowing himself to lie down, even for a brief moment. As soon as Theodosius sat down, the cave would echo with the stomping of many demons, as though some were riding in chariots, others beating drums, and yet others blowing trumpets, all yelling so fiercely that the cave shook with the terrifying noise.

However, the monk remained unafraid and undismayed. He would make the sign of the cross, rise, and begin reading the Psalter. Immediately, the dreadful noise would cease. Thus, with God’s help, Theodosius triumphed over the evil spirits.

In the 17th century, the cave life was embraced by Job of Lgov. When he and his disciples settled on the Lgov Hills, they dug a small cave for themselves. Later, a black deacon named Arseny came from Moscow to join them, and together they dug further. They carried out the earth on their shoulders while singing psalms. Eventually, they dug new caves and long tunnels, above which Job built a church in honor of the Great Martyr Demetrius of Thessalonica.

Such was the arduous feat of cave-dwelling. In the 18th century on Vyetka, the monk Vikentiy Kroupski became famous for this same ascetic labor.

Vikentiy came to Vyetka from Moscow during the early years of settlement, at the end of the 17th century. Having escaped the “Vyetka Expulsion,” the monk settled in the Monastery of Lavrenty. There, he distinguished himself with a pious life and extraordinary asceticism, eventually taking the great schema.

After living in the monastery for five years, Vikentiy, with the abbot’s blessing, left for a solitary hermit’s life near the Russian border. Close to Lavrenty’s Monastery, near the village of Kroupsk , the monk dug a cave into a hill with his own hands and settled there.

From the cave, a secret door led to a narrow passage with various branches, where icons and crosses were placed in small alcoves. In one spot, Vikentiy dug a well, the water from which was later venerated as holy. The passage ended in a narrow cellar where the hermit lived.

Through tireless prayer, fasting, vigils, and wearing chains, the elder was filled with miraculous grace. It was said that Vikentiy possessed extraordinary clairvoyance and the gift of prophecy. Once, after long prayer, he fell into a spiritual ecstasy and experienced a divine vision.

Monks began to gather around Vikentiy. Near his cave, a skete with two chapels and several cells emerged. After a short while, a community of Old Believers formed around the skete, giving rise to the village known as New Kroupsk.

The fame of the great ascetic and steadfast defender of Orthodoxy drew more and more disciples to Vikentiy, and soon his community surpassed the monks of Lavrenty’s Monastery in the strictness of their monastic life.

In 1773, a year after the Vyetka settlements were transferred from Poland to Russia, Vikentiy passed away at almost one hundred years of age. His body, emaciated by fasting, vigils, prayer, chains, and labor, was found incorrupt.

The news of the saint’s relics spread throughout the Christian world. The skete’s inhabitants placed the relics in a wooden coffin and set it in the very cave where the elder had lived. Prayers were offered there daily from morning till evening.

Pilgrims, not only from the Old Believer settlements but also from nearby Belarusian villages, flocked to venerate Vikentiy’s relics. They took sand from the cave and water from the well that the saint had dug.

By the faith of those who took the sand and water, various ailments were healed. Miracles occurred at the tomb of this new servant of God. A life and account of Vikentiy’s miracles were written, but unfortunately, they have not survived.

In 1774, a local Nikonian priest, Ivan Yelansky, reported the relics to the authorities. An investigation began, in which even the Holy Synod took part. The following year, a decision was made: officials and soldiers were sent to New Kroupsk to inspect the relics and then bury them in a secret place so that the Old Believers could not find them.

However, the officials and soldiers acted in their own way. They burned Vikentiy’s body, sealed his cave, destroyed the skete, and scattered the monks.

On the site of the burned relics, on the ashes, the Old Believers found charred bones, parts of the elder’s clothing, and his heart, which remained completely intact. The faithful placed the remains in a small tin box and secretly brought them to Lavrenty’s Monastery.

The elder’s chains, bought at a great price from the Nikonians, were sent to Gomel. Now pilgrims came to Lavrenty’s Monastery to venerate Vikentiy’s relics. When Lavrenty died, he bequeathed to his successor the task of returning the holy relics to New Kroupsk, which was done.

In 1839, the authorities destroyed Lavrenty’s Monastery. The threat of destruction hung over the other monasteries in Vyetka and Starodub. At that time, Vikentiy’s relics were taken to Dobruja. Their further fate remains unknown.

The Pugachev Rebellion #

The order of succession to the Russian throne, established by Peter I, was flawed. As a result, in the 18th century, many rulers, mostly women, occupied the Russian throne. Often, a new ruler’s ascension was accompanied by a military coup.

In 1741, with military support, Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter, ascended the throne. She had no children, so she declared her nephew, Charles Peter Ulrich, her successor. This German prince was the son of Elizabeth’s sister, Princess Anna Petrovna, and Charles Frederick, the ruler of the small state of Holstein-Gottorp.

In 1742, Charles Peter Ulrich moved to Russia and was given the Russian name Pyotr Fyodorovich. Three years later, he married the German princess Sophia Frederica Augusta, who became known in Russia as Catherine Alexeyevna—future Empress Catherine II. In 1754, the couple had a son, the future Emperor Paul I.

There was every reason to believe that Peter would be an ineffective ruler. Weak-willed and fond of alcohol, he adored everything German, especially the strict customs of the German army. He thought more about distant Holstein-Gottorp than about Russia.

Elizabeth Petrovna died in 1761, and her nephew ascended the throne, but his reign was short-lived. The following year, another palace coup occurred, with Peter being overthrown by his own wife. The deposed emperor was imprisoned in a palace, where he died under unclear circumstances—possibly due to excessive drinking or being murdered by his wife’s supporters.

During the reign of Catherine II, several pretenders emerged, claiming to be the “legitimate ruler, Pyotr Fyodorovich.” The most famous of these pretenders was Yemelyan Pugachev, an illiterate but brave and resourceful Cossack.

The Pugachev rebellion is the subject of Alexander Pushkin’s novella The Captain’s Daughter, well known to every schoolchild. This novella is one of the best works of Russian literature and is of particular interest to us because it partially touches on the history of the Old Believers. After all, Old Believers—Cossacks from the Don and the Yaik—participated in Pugachev’s uprising.

Yemelyan Pugachev was born in 1742 on the Don in a Cossack family. It is widely believed that Pugachev was an Old Believer, but this is incorrect. During interrogation, he said:

— Until I was seventeen, I lived with my father. However, I am not a schismatic like most Don and Yaik Cossacks, but of the Orthodox Greek faith. And I make the sign of the cross with three fingers.

Nevertheless, Pugachev had extensive contact with Old Believers. He lived in Old Believer settlements in Starodub and Vyetka, and when it was convenient, he passed himself off as an Old Believer.

In the fall of 1772, Pugachev settled at the Presentation of the Theotokos Skete on the Irgiz River, an Old Believer community led by Abbot Filaret (Semyonov). From him, Pugachev learned about the recent Yaik Cossack rebellion.

The uprising had begun in January 1772, sparked by the encroachments of imperial officials on the ancient freedoms of the Cossacks. By June, the rebellion was crushed. Many of the rebels were executed, branded, or sent to forced labor. Some even had their tongues torn out.

The Cossacks became embittered and began contemplating revenge against the government. Some spoke of following the example of the Nekrasovites—Cossacks who had fled to the Kuban—rather than remaining in Russia. The conditions for a new uprising were ripe.

At that point, Pugachev appeared, claiming to be Tsar Pyotr Fyodorovich. Few Yaik Cossacks believed the impostor, but many joined him.

The rebellion began in September 1773. The Cossacks were joined by serfs and workers from the Ural factories. Pugachev promised various freedoms to those who recognized him as tsar, including the freedom to cross themselves with two fingers, pray according to the old books, and wear beards.

Pugachev’s envoys traveled through the villages, reading his decrees:

“We grant by this decree, with our paternal mercy, that all those formerly in serfdom and under the landlords shall now be loyal subjects of our own crown. We bestow upon you the ancient cross and prayer, heads and beards, freedom, liberty, and the eternal status of Cossacks.”

These decrees had a powerful effect on the people, and commoners flocked to Pugachev’s army by the thousands. He gained the support of not only Russians but also various peoples of the Volga and Ural regions—Kalmyks, Bashkirs, Tatars, Chuvash, Mordvins, and Mari.

The banks of the Yaik, Volga, and Kama were engulfed in a bloody uprising.

Sometimes, after capturing a village or fortress, the rebels would demand that the local clergy henceforth conduct services according to the pre-Nikonian books. Frightened, the clergy complied with these demands.

However, Pugachev’s ignorance sometimes led to absurd incidents.

When the rebels entered a Cossack stanitsa (village), the priest met them with a cross. Pugachev kissed the cross and entered the stanitsa church. The royal gates of the iconostasis were open, and the impostor walked into the sanctuary, sat on the altar, and said:

— It’s been a long time since I sat on the throne!

The illiterate Pugachev had confused the church altar with the royal throne…

Catherine II sent troops to crush the impostor’s uprising. The rebels, poorly armed and disorganized, could not withstand the well-armed and disciplined imperial army. After suffering defeats, the rebellion’s leaders decided to capture Pugachev and hand him over to the authorities in exchange for amnesty.

The impostor was seized by his own comrades on September 8, 1774. A week later, in the Yaik town, the main Cossack stronghold, the bound Pugachev was handed over to officers.

Pugachev was transported to Moscow in a cage. Interrogations, investigations, and a trial ensued. The impostor was sentenced to death.

Along with Pugachev, some of his companions were also captured and sentenced to execution, including Yaik Cossacks and Old Believers Afanasy Perfiliev and Maxim Shigayev.

On the eve of the execution, a Nikonian priest came to the prison, tasked with hearing the confessions of the prisoners. The impostor repented, but Perfiliev and Shigayev refused to confess.

The next morning, on the day of the execution, January 10, 1775, the priest again came to the prison and gave communion to Pugachev in the new rite. Perfiliev and Shigayev refused communion.

The condemned were then taken to Bolotnaya Square, where the block and gallows awaited. Pugachev and Perfiliev were beheaded, while the others were hanged.

Thus ended the rebellion. By order of Catherine II, to forever erase the memory of the uprising, the Yaik River was renamed the Ural, and Yaik Town was renamed Uralsk.