The Search for a Bishop #

We know that God is not the God of the dead, but of the living . In God, all are alive. Thus, the Holy Church consists not only of Christians who are currently alive but also of the righteous who have passed on. In the 18th century, this belief comforted the Old Believers with the thought that, although they had no living bishop, all the departed hierarchs—from the ancient apostles, the first bishops, to the martyred Pavel of Kolomna—were invisibly present with them.

However, the constant shortage of priests and the ever-present fear of losing them compelled the Old Believers to seek out a living Orthodox bishop, a reliable and permanent source of holy orders. Proper church governance is only possible with a bishop—a high priest, archpastor, and successor of the apostles.

The search for a bishop began in the 18th century. Both the Popovtsy (priestly Old Believers) and Bespopovtsy (priestless Old Believers) participated in these efforts. From the Vygo Monastery, Andrey Denisov first sent a man named Leonty Fedoseev and later the learned elder Mikhail Vyshatin to search for a bishop, but their quests were unsuccessful.

In their search for a bishop, the Old Believers had two goals. First, they sought to find a pious hierarch and convince him to join the Russian Church. Throughout the 18th century, Old Believers scoured not only Russia but also Turkish lands—Moldavia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Palestine.

But they did not find a supreme pastor who, like Christ the Good Shepherd, would lay down his life for his sheep. The fear of the tsarist authorities, of the torture rack and the whip, of imprisonment and exile, proved stronger than Christian love.

However, in 1731, a bishop was unexpectedly found—not in distant lands, but in Moscow itself. Here, in prison, languished Bishop Epiphanius (Yakovlev), a Little Russian from Kiev who had been consecrated as a bishop by the Metropolitan of Moldavia.

Since, according to the laws of the time, Russians were forbidden to receive ecclesiastical ranks abroad, Epiphanius was arrested as soon as he returned to his homeland and was imprisoned. While in prison, he became acquainted with wealthy Old Believers who regularly gave alms to prisoners. They convinced Epiphanius to join their Church and helped him escape to Vetka in 1733.

However, the long-awaited arrival of a bishop was met with caution by the Old Believers. The problem lay in the fact that Epiphanius was from Little Russia, where baptisms were performed according to the Latin rite—by pouring, rather than immersion. The Old Believers could not accept a bishop with such a form of baptism.

While they were deliberating on what to do with Epiphanius, news of the bishop’s presence in Vetka reached Empress Anna Ioannovna. Enraged, the empress blamed Epiphanius for instigating the “Vetka eviction” of 1735. Tsarist troops invaded Vetka, ravaging it. The bishop was captured, taken to Kyiv, and once again imprisoned, where he later died.

Another Old Believer bishop in the mid-18th century was Bishop Theodosius. Like Epiphanius, he did not leave a significant mark on church history. Theodosius, a Cossack and native Old Believer, was consecrated a bishop for the Cossacks living in Kuban, which at that time was under the control of the Crimean Khan. He was consecrated by a Greek archbishop at the request of the Old Believers and the insistence of the khan. Theodosius died without leaving a successor.

In their search for a bishop, the Old Believers also dreamed of finding a land where ancient piety was still preserved in its entirety. In the 18th century, rumors of such blessed lands occasionally reached the Old Believers.

Some said that Orthodoxy flourished in Japan—in the Opon Kingdom, which stood on the ocean. Others claimed that the old rites were still observed in the temples of the Kingdom of Belovodye, hidden somewhere in Asia.

From time to time, people appeared in Russia claiming to have visited the Opon Kingdom or Belovodye. Occasionally, letters would arrive from these places, describing the triumph of the faith, the splendor of the churches, and the devout service of pious bishops.

In the late 19th century, a peculiar man named Anton Pikulsky—a civil servant’s son from Veliky Novgorod—traveled across Russia, claiming to be Archbishop Arkady, allegedly consecrated by the Patriarch of the Belovodye Kingdom.

But by that time, it was no longer easy to deceive people, and Pikulsky failed to gain followers…

Throughout the 18th century, the Polish Kingdom weakened and diminished. Strong neighbors—Austria, Prussia, and Russia—gradually took parts of its territory until Poland ceased to exist altogether. In 1772, the city of Gomel and the Vetka settlements were ceded to the Russian Empire.

Some Old Believers of Vetka and Starodub, disillusioned and wearied by their fruitless search for a bishop, began to speak of reconciling with secular and spiritual authorities and requesting a bishop and priests from the capital, Saint Petersburg, under Empress Catherine II and the hierarchs of the Synodal Church.

The first to express this idea was the monk Nikodim from Starodub. In 1783, he submitted a petition to the empress, requesting that a bishop be sent to the Old Believers from the Synod. However, Nikodim died a year later, and with him died his initiative.

In 1799, several merchants, parishioners of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery, submitted a petition to Metropolitan Platon (Levshin) of Moscow, asking for permission to receive priests from the Synodal Church. The metropolitan agreed to fulfill this request and take the Old Believers under his protection, but only on the condition that they recognized the authority of the Synod over them.

Thus, Yedinoverie (the union of Old Believers and the mainstream Orthodox Church) was born. It was similar to the earlier Unia (the union of Orthodox Christians with the Latin Church). The Yedinovertsy (those in the union) were completely subordinate to the Synod and received priests who served according to the old books. They also gained the right to freely build churches and monasteries and establish schools and printing presses.

Emperor Paul I signed the rules for the establishment of Yedinoverie on October 27, 1800.

However, Platon and other Synodal hierarchs believed that the old church books contained errors due to ignorance. They therefore treated their new flock with disdain, viewing them as a gathering of the unlearned. In the Synod, Yedinoverie was referred to as a “church ailment.”

The Old Believers, for their part, regarded Yedinoverie as a trap. At the beginning of the 19th century, only a small number of Christians joined the Yedinoverie. The number of adherents increased only under Tsar Nicholas I, when Old Believers were forcibly incorporated into the Synodal Church.

Emelyan Pugachev’s Appeal #

(from a letter to the Cossacks of Berezovskaya Stanitsa)

By the grace of God, we, Peter the Third, Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia, make known the following.

This proclamation is addressed to the ataman of the Berezovskaya stanitsa and to all the Cossacks of the Don army living therein, as well as to all the people. Russia has long been filled with rumors of our concealment by evildoers (chief senators and nobles), and foreign states are not unaware of this. It is no other cause that brought this about but that during our reign, it was observed that the aforementioned evildoers—the nobles—had completely violated and trampled the Christian law and the ancient traditions of the holy fathers. In its place, they introduced into Russia another law, devised by their malicious schemes, from German customs, including the most God-despised practice of shaving beards and various outrages against the Christian faith, both in regard to the cross and in other matters.

They subjected all of Russia to their rule, apart from our monarchal authority, laying great burdens upon it and bringing it to the brink of utter destruction. As a result, the Yaik, Don, and Volga armies were expecting their complete ruin and extermination. We, having deeply lamented all of the above, were resolved to free the people from their tyrannical oppression and to bring freedom to all of Russia. For this, we were unexpectedly deprived of the All-Russian throne and, through the malicious decrees that were published, were declared dead.

But now, by the providence of the Almighty hand and by His holy will, instead of being entirely forgotten, our name has flourished… Therefore, we have deemed it proper, through this our most gracious decree, to make known our advance with a victorious army, both to the aforementioned Berezovskaya stanitsa and to the entire natural Don Cossack army. If they sense our fatherly care and wish to stand with their natural sovereign, who has endured great hardships and not small sufferings for the sake of common peace and tranquility, let those who desire to show zeal and dedication in the destruction of those nobles harmful to society appear in our main army, where we ourselves are present. For this, they shall not be left unrewarded, without our monarchal grace, and on the first occasion will receive ten rubles as a token of their service.

Rogozhskoye Cemetery #

In 1762, Empress Catherine II ascended the Russian throne. A wise and calculating sovereign, she understood the benefits that wealthy Old Believers—industrialists and merchants—could bring to the country.

That same year, she issued a decree inviting fugitive Old Believers, primarily the inhabitants of Vetka, to return to Russia. They were promised privileges: permission not to shave their beards and to wear traditional clothing, as well as exemption from taxes for six years.

The decree was followed by a series of orders improving the position of the Old Believers. Peter I’s laws on shaving beards, Russian dress, and the double poll tax were repealed. It was forbidden to call adherents of the ancient church tradition “schismatics”; from now on, they were to be called “Old Believers.”

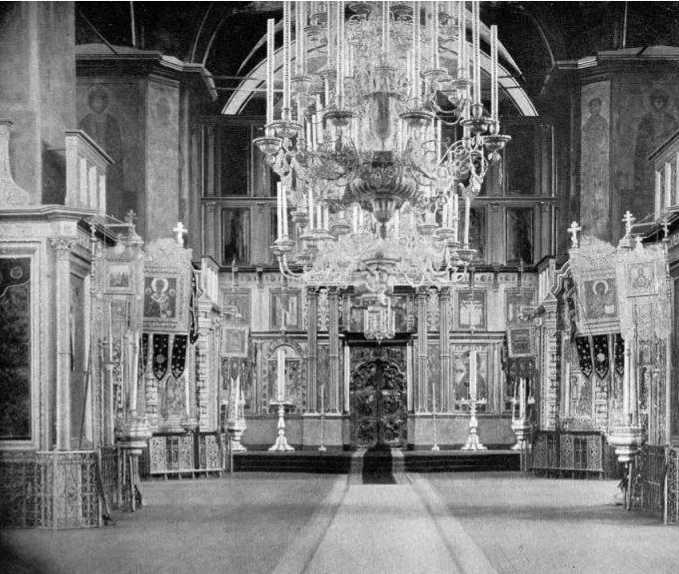

It was only during the reign of the gracious Catherine that something unprecedented occurred: in Moscow itself, right under the noses of the highest ecclesiastical and secular authorities, the Old Believers freely built enormous, magnificently decorated churches.

The churches were built under the following circumstances.

In December 1770, a plague broke out in Moscow, intensifying particularly in March 1771. Hundreds of people were dying daily. By order of the authorities, all cemeteries in the city were closed. The dead were buried in mass graves in the churchyards of villages around Moscow.

Among the closed cemeteries were two Old Believer burial grounds. These special churchyards, with chapels dating back to 1718, belonged to the priestly Old Believers. One was located near the Serpukhov Gate, the other near the Tver Gate.

For new burials, the priestly Old Believers were allocated land three versts from the Rogozhsky Gate. At the same time, the priestless Old Believers were allowed to establish their own cemetery near the village of Preobrazhenskoye. Thus, the famous Rogozhskoye and Preobrazhenskoye Old Believer cemeteries came into being.

When Rogozhskoye Cemetery was established, a small wooden chapel in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker was built. In 1776, it was replaced by a larger stone church.

In 1791, with permission from Moscow’s governor Prozorovsky, the construction began on the unheated summer chapel in honor of the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos, which for a long time was the largest of all the city churches. Originally, it was intended to accommodate up to three thousand worshippers, with altar apses and five domes.

The scale of the construction became known to Metropolitan Gabriel (Petrov) of St. Petersburg. He sent a report to the empress stating that the Old Believers “have begun building a church larger than the Assumption Cathedral, so that by its size they might diminish the first Church in Russia in the minds of the common people.”

Prozorovsky was forced to explain himself to Catherine and hurriedly ordered the apses to be demolished, the size reduced, and the church built with only one dome. This explains the somewhat awkward appearance of the Protection Cathedral—it resembles a large, but simple house.

Nevertheless, according to tradition, the empress graciously donated to the Moscow Old Believers a large altar Gospel in a silver setting, which was reverently kept in the altar of the Protection Church.

In 1804, the Old Believers managed, without complications, to build the heated winter chapel in honor of the Nativity of Christ.

Christians, who had lost the ancient Russian holy places—the cathedrals of the Moscow Kremlin—after the schism, created new shrines at Rogozhskoye Cemetery: the Churches of St. Nicholas, the Protection, and the Nativity.

These churches were lavishly adorned by the parishioners—wealthy Moscow merchants. The churches housed icons of the finest ancient craftsmanship, set in silver-gilt frames adorned with precious stones and pearls, silver candlesticks with massive candles, gilded iconostases, and magnificent liturgical vessels.

Unfortunately, only the Protection Cathedral has preserved its decoration to this day.

Around the cemetery, the Rogozhskaya Sloboda grew. Besides the churches, there were hospitals, almshouses, orphanages, priests’ houses, and five women’s monasteries.

Nuns and novices constantly read the Psalter for the deceased and also engaged in needlework: embroidering with silks, gold, and beads, weaving belts and prayer ropes, spinning flax, and weaving linen.

A special office, managed by trustees, was established to oversee the cemetery and almshouses. The office would send priests to distant places at its discretion to perform church services. Priests carried with them reserve Gifts, chrism, and holy water. In its best years, twelve priests and four deacons served at Rogozhskoye Cemetery.

The most famous and respected clergyman of the cemetery was Priest Ioann Matveevich Yastrebov (1770–1853). In 1803, convinced of the truth of the old faith, he left the Synodal Church and moved to Rogozhskaya Sloboda. Here, Ioann lived with his wife Euphemia for fifty years.

The churches of Rogozhskoye Cemetery were considered chapels without altars, so only Vespers, Matins, Midnight Office, Hours, and Prayer Services were performed in them, along with baptisms, confessions, and weddings. The dead were sung over in the Chapel of St. Nicholas.

Infant baptisms were performed in the Nativity Chapel, which contained 46 fonts. Priests heard confessions in the churches or sometimes at their homes. Those who had fasted and confessed received the Eucharist in the chapels from the reserve Gifts.

Once a year, on Great Thursday, secretly to avoid the authorities’ wrath, the priests celebrated the Liturgy for the consecration of the reserve Gifts using a portable field church. It resembled a tent, inside which a folding altar with an antimins was set up. In case of danger, this church could be quickly dismantled and hidden.

In 1813, after the end of the war with France, Moscow was occupied by Don Cossacks, many of whom were Old Believers. They sought spiritual support at Rogozhskoye Cemetery.

According to tradition, the famous military leader Ataman Matvei Ivanovich Platov (1751–1818) was an Old Believer. On his return to the Don after defeating the French, he gifted the cemetery an ancient field church, consecrated in honor of the Holy Trinity. The authorities allowed services to be held there on major holidays.

These services, which gathered thousands of worshippers, were celebrated in the chapels with great reverence and piety. However, in 1823, Emperor Alexander I, the grandson of Catherine II, received a report about the solemn services at the cemetery. A search was conducted, and Platov’s field church was confiscated.

Tsar Nicholas #

The journey of many clergymen who converted to the Old Belief from the State Church began in Moscow at the Rogozhskoye Cemetery. They were brought here in secret, so the police would not find out. Here, they were anointed with chrism and left at the chapels to learn the proper way to serve according to the old books.

From Moscow, mysterious letters spread across Russia: “We found salt, but it was raw, so we dried it on a rush mat and stored it in a granary.” This meant that the Old Believers had found a priest from the Synodal Church (“raw salt”), performed the chrismation on him at Rogozhskoye Cemetery (“dried it on a rush mat”), and placed him at a church (“stored it in a granary”).

From there, the priests would travel to different parishes. They also found their final resting place at the cemetery. There was a special burial place for them, marked by a memorial cross with the inscription: “This cross of the Lord is set in memory of the clergymen who rest here with their bodies. They were always struck by the fear of external persecution and wearied by the internal deprivation of a pious episcopate. And in such cruel turmoil, like brave sailors without a helmsman, they saved the ship of the Church from sinking.”

Another cruel turmoil, which nearly sank the ship of the Church, began under Emperor Nicholas I. The situation of the Russian Church under him became completely unbearable.

Nicholas Pavlovich ascended the throne in 1825 after the death of his elder brother, Emperor Alexander I. The new autocrat adored strict military order—polished boots, the beat of drums, and soldiers’ obedience. He dreamed of turning the entire country into a barracks. But the Old Believers, independent of the Synodal Church, disrupted the orderly ranks of the tsar’s subjects.

In the army of that time, a soldier could be beaten with sticks, starved, sent to penal servitude, or executed for the slightest offense. The emperor decided that he could treat the Old Believers the same way, forcing them into submission through power and fear.

Once again, Christians were subjected to brutal persecution. Nicholas’ actions were blessed by Metropolitan Philaret (Drozdov) of Moscow.

To him, priests were the same kind of state officials as civil servants or military officers. Thus, he was irritated by Old Believer priests who had left the State Church. Philaret compared them to deserters—soldiers who had fled from service. He wrote: “The idea of allowing an official to desert or hide wherever he wants without punishment is destructive to public order. By law, a runaway priest, like any fugitive, should be caught immediately and sent to trial.”

The persecution of Old Believer clergy began in 1827. The tsarist government passed two laws aimed against “runaway priests.” From then on, they were not allowed to travel from place to place to visit their flocks. Furthermore, Old Believers were henceforth forbidden from accepting clergymen from the Synodal Church.

The main instrument of the government’s struggle against Old Belief became Edinoverie (Unity of Faith). Through it, both priestly and priestless Old Believers were forcibly joined to the State Church.

For refusing to accept Edinoverie, hundreds of churches and monasteries across the country were closed. With unprecedented cruelty, priestly monasteries in Starodub, Vetka, and Irgiz, as well as the priestless Vyg Monastery in Pomorye, were destroyed. The horror among the Old Believers was so great that some declared Nicholas to be the Antichrist, just as they had previously done with Peter I.

The priestly Old Believers found themselves in a completely hopeless situation. Due to the new persecutions, their priesthood, already small in number, was disappearing before their very eyes. The priestly Old Believers were facing a bleak future—being forced to become priestless.

At Rogozhskoye Cemetery, talk began about converting to Edinoverie. Quarrels and disputes broke out. Priest Ioann Yastrebov put an end to them. He proposed to the Muscovites to hold a church service in the Nativity Chapel, after which a general council would make a final decision regarding Edinoverie.

That evening, the church filled with praying people—a Vigil had begun. After the morning service, a solemn procession passed around the Nativity Chapel. Then, a cross and the Gospel were carried to the center of the church. The priest stepped forward.

All eyes turned to him. Without allowing any debate to begin, the priest raised his hand with the two-fingered sign of the cross and declared: “Stand firm in the true faith and for the right cross until your last drop of blood! Whoever follows the true faith of Christ, come forward and kiss the cross and the Gospel. But whoever does not wish to remain in this position—leave now!”

Yastrebov was the first to kiss the cross and the Gospel, followed by all who had gathered. Thus, the Muscovites resisted the temptation of Edinoverie, remaining faithful to Orthodoxy.

But the persecutions led to a complete shortage of clergy. The situation was dire. The Church needed to find a reliable and permanent source of priesthood. Only a pious bishop could provide it.

In January 1832, a large council was held in Moscow. Christians from all over Russia gathered: respected priests, pious monks, and zealous laymen. Ioann Yastrebov announced to the assembled that among them was a worthy man with great news to share: “He will reveal to you this mystery. He will show a way to forever avoid the difficulties of lacking priests. He will give our God-saved community new strength, firmness, and life. Here he is! Open your ears and listen to him!”

The priest brought forward a young merchant, Afoniy Kozmich Kochuyev (1804–1865), a well-known preacher and expert in church canons. With rare eloquence, Kochuyev described the Church’s dire situation caused by the persecutions and the lack of clergy.

He spoke about how the only way to preserve the Church was to establish a residence for a bishop abroad and to invite a worthy Russian or Greek bishop there: “We must, without delay, establish an episcopacy. We must search for bishops who have retained the ancient piety. And if none can be found, invite Russian ones. And if they refuse, then invite Greek ones. And accept them according to the canons of the holy fathers. The residence must be established abroad, and the best place for it is Bukovina.”

Kochuyev’s proposal was unanimously approved. Under the cover of the deepest secrecy, new searches for a bishop began.

Belaya Krinitsa #

The region of Bukovina, lying at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains, has always attracted conquerors. In the 16th century, these fertile lands were seized by Turkey. But in 1775, it was forced to cede them to the stronger Austria. In the 20th century, Bukovina belonged to Romania and the Soviet Union. Today, this region is divided between Ukraine and Romania.

At the time we are discussing, Bukovina was a district of the Austrian Empire. Numerous Old Believers lived there, enjoying the protection of the authorities. They were called Lipovans.

The Old Believers had resettled here in the 18th century from Russia and Turkey, from the regions of Moldavia and Dobruja. At that time, Bukovina had been ravaged by wars and lay desolate and depopulated. Thus, the Austrian authorities welcomed the arrival of settlers to these abandoned lands.

The governor of Bukovina reported to the Austrian capital, Vienna: “These Lipovans are an exceptionally peaceful, diligent, quiet, hardworking, neat, very sensible, and generally strong and robust people. Each of them is required to master a craft, which, along with agriculture, they use to best support themselves. They regard drunkenness and foul language as the greatest vices, and it is said that drunk Lipovans have been seen very rarely. Their clothing, especially among the women, is attractive, neat, and dignified. And they are very inclined to do good to their neighbors, whoever they may be. Throughout my service here, not a single complaint has been received against these truly worthy, good people.”

Austrian Emperor Joseph II, receiving such a favorable report, ordered that as many Lipovan families as possible be encouraged to settle in Bukovina.

In 1783, he signed a decree regarding the Old Believers, which stated: “We allow them complete freedom of religious practices for themselves, their children, and all their descendants, along with their clergy.”

This freedom of religion attracted both priestly and priestless Old Believers to Bukovina. In the village of Belaya Krinitsa, a priestly male monastery was established with a church dedicated to the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos. It was here that the future Old Believer bishop was to be placed.

In 1839, two monks from Russia, Pavel (Velikodvorsky) and Heronty (Kolpakov), arrived at the Belaya Krinitsa monastery on a mission to find a bishop.

Pavel began working on establishing a residence for a bishop at the monastery. This required great effort. The monk had to draft numerous documents and deal with various officials in different institutions. Pavel and Heronty even had to travel to Emperor Ferdinand I himself in Vienna.

In the capital, the monks sought the patronage of an important court official. He asked: “What do you want to arrange for yourselves?” “We want to find a bishop,” the monks replied. The official then showed Pavel and Heronty his hand and said: “When hair grows on the palm of my hand, then you will have a bishop. Or I will not be alive!”

The monks, horrified by such a response, consoled each other: “Every good beginning comes with trials.”

And it so happened that three days later, the court official unexpectedly died!

On September 6, 1844, the emperor signed a decree: “It is permitted to bring in from abroad one clergyman, specifically an archpastor or bishop, with the stipulation that he may ordain the Lipovan monks at Belaya Krinitsa to higher orders and also be able to ordain priests, as well as select and consecrate his successor.”

After this, Pavel, with a new companion—monk Alimpiy (Miloradov)—set off to search for a bishop willing to join the Old Believers. Heronty remained at the Belaya Krinitsa monastery, where the brethren elected him as the abbot.

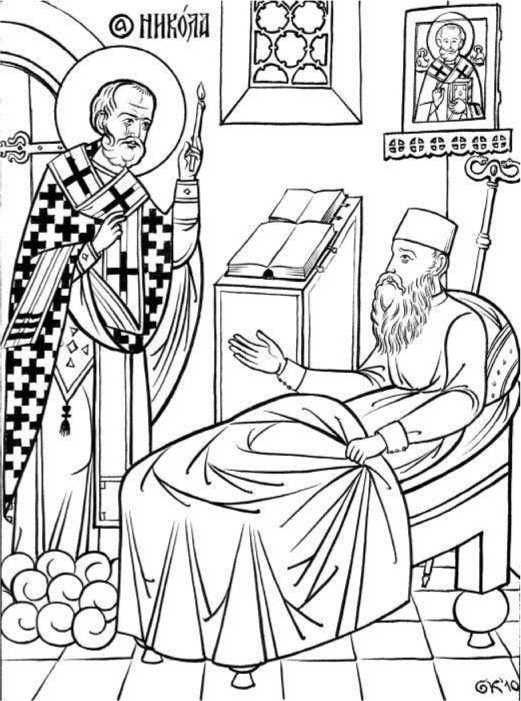

From his youth, Pavel had been visited by visions of St. Nicholas, calling him to serve a great cause. And now the time for this cause had come! As he embarked on it, the monk was anxious and prayed, invoking Nicholas the Wonderworker.

And then one night, in a dream, the saint appeared to Pavel and said: “The time appointed by God has drawn near. This task has been given to you by God. And I will be with you as a helper in all places.”

The monk, upon waking, did not give much significance to the dream. The vision repeated the next night, but again the monk did not believe it.

On the third night, while Pavel was praying earnestly, Nicholas appeared before him in bishop’s vestments, holding a church in one hand and a sword in the other. The saint sternly said to the astonished monk: “Do not resist God’s providence! God has commanded me to appear clearly as confirmation. If you still doubt, the sword you see will strike you.”

Encouraged by this extraordinary vision, Pavel and Alimpiy set off on a long journey. Before leaving the monastery, they prayed: “Lord, if the task we begin will be of benefit, guide and help us. But if it is not beneficial, shorten our lives on the way, O Lord!”

The monks traveled throughout the Christian East, visiting Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and Constantinople-Istanbul. There, they met Greek Metropolitan Ambrose. He impressed the monks, and they invited the bishop to join the Russian Church.

The metropolitan hesitated in giving an answer. Seeing his indecision, Pavel and Alimpiy decided to return to Belaya Krinitsa. But on their final visit to Ambrose, they unexpectedly heard from him: “I have decided to go with you!”

The delighted monks asked: “Why, Your Eminence, have you now agreed to our proposal, while yesterday you did not?”

The metropolitan told them of an extraordinary vision: “Yesterday, after seeing you off, I was preoccupied with the thought: is this offer good for me? With this thought, I prayed to God and went to bed. But I had not yet fallen asleep when suddenly a radiant man appeared before me and said: ‘Why do you weary yourself so much with thoughts? This great work has been destined for you by God, and you will suffer for it from the Russian tsar.’ At the word ‘suffer,’ I shuddered and awoke, but there was no one there. Only light was visible in the room, gradually fading, as if someone was walking away with a lit candle. My heart was filled with both fear and joy, so much so that I spent the entire night without sleep, praying to God. And I decided to give you my full consent, for if this is God’s will, we must carry it out with joy.”

The radiant man who had appeared to the metropolitan was St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. Thus, this great work, which began with the appearance of God’s servant, was successfully completed with his miraculous assistance.

Metropolitan Ambrose #

In 1791, in the Greek village of Maïstra, which had been taken over by the Turks, a son named Andrei was born to the priest Georgios. Georgios was the twenty-second priest in his family line, and no one doubted that his son would inherit his vocation. From childhood, his father prepared Andrei for the priesthood.

The young man entered a theological school. In 1811, he married and was ordained a priest. Soon after, Andrei was widowed, left to care for his young son, Georgios. In 1817, he took monastic vows and was given the name Ambrose.

The local bishop took the hieromonk as his assistant. Through his pious conduct and good education, Ambrose earned the respect of the bishops of the Greek Church. In 1823, he was appointed abbot of the Trinity Monastery on the island of Halki.

The Patriarch of Constantinople, Constantius, took notice of Ambrose. He transferred the capable hieromonk to Istanbul and entrusted him with the important position of Grand Protosyncellus, the patriarch’s closest assistant.

In 1835, Metropolitan Benjamin, the archpastor of the Orthodox Serbs living in Bosnia, passed away. Ambrose was chosen to take his place. He was consecrated a bishop by the patriarch, assisted by four other hierarchs.

What did Ambrose see when he arrived in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia?

The Slavic land was under Turkish rule. The Muslims oppressed the Christians, and the Bosnian metropolitans did not intervene. But the new hierarch was not like them.

A true shepherd, he felt the suffering of his flock with all his heart and strove to ease their plight. A kind and just man, he could not look indifferently upon the afflictions of the Serbs and took their side.

This was so unusual, so contrary to the popular perception of haughty Greek hierarchs, that the Serbs refused to believe Ambrose was Greek. Since the metropolitan spoke Slavic well, a rumor spread that he was a native Slav—a Bulgarian.

In 1840, driven to despair, the Serbs, under the leadership of a certain Glodja, rose in rebellion against the pasha, the Turkish governor. Metropolitan Ambrose sided with the rebels, declaring:

— The people’s ruler is the one whom the people support!

The uprising ended in tragedy. The Muslims incited the Bosnian merchants to write a denunciation against Ambrose to the patriarch, accusing him of “meddling in dangerous affairs, conspiring with Glodja, and slandering the pasha.”

At that time, the patriarch was Anthimus, a timid and weak man. He understood the true nature of the accusations against the metropolitan but did not dare to contradict the Turkish authorities. In 1840, Anthimus recalled Ambrose to Istanbul. There, the hierarch lived under the patriarch’s patronage, receiving a decent allowance.

In 1844, Metropolitan Ambrose met the monks Paul and Alimpius. They were immediately drawn to him by his kindness and attentiveness. They often conversed about matters of faith, including Old Belief.

The stories of the monks touched the saint’s heart. He was filled with love for the Russian Old Believers, who suffered at the hands of their own government in a manner comparable to the suffering of the Greeks and Slavs under the Turkish yoke.

The monks spoke of how the ancient Greek Orthodox tradition had been preserved only in the Russian Old Faith. After these conversations, convinced of the truth of Old Belief, Ambrose desired to join it.

Together with the monks, his son Georgios, and his daughter-in-law Anna, he set off for Austria. At the end of May 1846, the hierarch left Istanbul, telling the patriarch that he wished to travel. Before his departure, Anthimus personally signed a letter permitting him to perform services.

Ambrose arrived in Vienna and was presented to Emperor Ferdinand.

He submitted a petition to the sovereign, in which he declared:

— I have firmly resolved to accept the election of the Old Believer community as its supreme pastor, seeing in this the clear providence of God, which has destined me to lead this community—hitherto deprived of a sacred archpastor—toward the path of eternal blessedness.

In his petition, the metropolitan also stated:

— I am fully convinced that all the statutes of the Greek Church are preserved in their original purity and accuracy only among the Old Believers.

From Vienna, the hierarch proceeded to Belaya Krinitsa. At the monastery, he took up residence in two small cells filled with icons, subsisting on simple monastic fare—soup or porridge, kasha, and fish.

Metropolitan Ambrose’s reception into the Church took place on October 28, 1846.

On that memorable day, the council of Belaya Krinitsa Monastery was packed with people. The archbishop entered the church and donned his episcopal vestments. Then he solemnly recited the rite of renouncing heresy:

— I, Ambrose, Metropolitan, come to the True Orthodox Church of Christ and anathematize the former heresies…

Then the hierarch entered the altar, and the hieromonk Jerome (Alexandrov) anointed him with chrism. Exiting the royal doors, the metropolitan blessed the people. The brethren sang “Many Years,” while the laity wept for joy and glorified God.

Together with Ambrose, his entire family joined the Old Belief.

After some time, a worthy Christian was chosen as the metropolitan’s successor. The lot fell upon the ustavshchik Cyprian Timofeev. He was tonsured and given the name Cyril. Ambrose consecrated him as a bishop for the Nekrasovite Cossacks living in Turkey.

When news of the Old Believers having their own bishops reached St. Petersburg, Tsar Nicholas demanded that Emperor Ferdinand punish Ambrose.

The hierarch was summoned to Vienna. He was given the choice of either returning to Istanbul or going into lifelong exile. At the same time, he was handed a letter from the patriarch, offering him protection.

To this, the hierarch replied:

— I have once embraced this religion and shall not turn back.

In July 1848, Ambrose received orders to go into exile in the city of Cilli. There he lived with his son’s family for fifteen years, strictly observing the monastic rule.

Envoys from Belaya Krinitsa visited him, bringing reserve Gifts for communion. The hierarch longed for the monastery and dreamed of returning there.

Gradually, Metropolitan Ambrose’s health declined. Dropsy, a severe illness, caused him unbearable suffering. Yet the saint continued to oversee church affairs until his very last moments.

On the morning of October 30, 1863, feeling the approach of death, Saint Ambrose prayed, received communion, and peacefully departed this life. His son buried him in the Greek cemetery in the city of Trieste.

The Belokrinitskaya Hierarchy #

The ecclesiastical structure, comprising the three degrees of priesthood—bishops, priests, and deacons—is called a hierarchy. This word is of Greek origin and translates into Russian as “sacred authority” or “sacred governance.”

The first bishop consecrated by Metropolitan Ambrose was Bishop Cyril. Then, Ambrose and Cyril consecrated Bishop Arkady (Dorofeev).

Thus, the fullness of the Orthodox hierarchy was restored. It came to be known as the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy, named after the village of Belaya Krinitsa.

News of Old Believer bishops spread throughout the world. The unexpected triumph of the old faith enraged Nicholas I, who was prepared to persecute Christians not only in Russia but also beyond its borders.

In October 1847, the Austrian ambassador in St. Petersburg reported to Vienna that he had spoken with the tsar about Ambrose. The sovereign demanded the immediate closure of the Belokrinitsky Monastery and severe punishment for the metropolitan.

Nicholas threatened that if this did not happen, he would take decisive action:

— I will have to do something. This is too important for us to leave unanswered!

A month later, the ambassador reported that the Russians intended to recall their envoy from Vienna if Ferdinand I did not yield to the tsar’s demands. A conflict between the two powers was brewing, fraught with the risk of war. Ferdinand was forced to send Ambrose into exile.

But the great ecclesiastical work had already been accomplished. The priesthood of the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy spread throughout Russia. It was embraced not only by the popovtsy and bespopovtsy but even by the Nikonians.

This alarmed the government. After all, the Old Believers were undermining one of the pillars of tsarist authority—the Synodal Church!

Nicholas was not satisfied with Ambrose’s exile. He wished to utterly eradicate Old Belief. The Belokrinitskaya hierarchy was declared illegitimate. Its bishops and priests were branded as “false bishops” and “false priests,” “impostors” and “mere laymen.”

The hierarchy was given a derogatory nickname—“the Austrian hierarchy.” Since Austria was an enemy of Russia, every popovets was declared an enemy of the tsar and the fatherland.

Neither the imperial government nor the state Church recognized Old Believer sacraments. For many years, the persecution of the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy became the chief concern of both secular and ecclesiastical authorities. Thousands of priests, officials, and police officers participated in it.

In 1853, Archbishop Anthony (Shutov) arrived from Belaya Krinitsa in Russia and took leadership of the Church. That same year, on December 19, the priest Ioann Yastrebov, who had acknowledged the authority of Anthony and the Belokrinitsky metropolitan, passed away. The last “runaway priest” in Moscow, Peter Rusanov, remained.

At the beginning of 1854, several wealthy parishioners of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery declared their conversion to Edinoverie and petitioned the authorities to establish a Synodal Church parish at the cemetery. Metropolitan Philaret wasted no time in seizing the opportunity.

The Nikolskaya chapel, along with all its icons, books, and vestments, was handed over to the Edinovertsy. The bell tower was also given to them, as bell ringing had been prohibited for Old Believers since 1826.

To this day, the Nikolsky church has not been returned to its rightful owners—the Old Believers.

The police conducted a search at the cemetery. However, all valuable items had been preemptively moved to the homes of prominent parishioners. Nonetheless, in the chapels and storerooms, they found thousands of priestly and diaconal vestments. There was also an incalculable number of icons. Among the discoveries were 517 handwritten and early printed books, including several rare and remarkable ones.

The most valuable icons and books were taken by the Edinovertsy. A significant portion of the icons was transferred to Nikonian churches, along with the candleholders and lamps. As for the clergy’s vestments, on Philaret’s orders, they were burned.

At the end of 1854, Peter Rusanov also joined Edinoverie. The authorities believed that Rogozhskoye Cemetery would now be completely destroyed. But it survived.

For the Church, the era of fleeing priests had ended, and the time of the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy had begun.

In 1855, Tsar Nicholas I died. His son, Alexander II, ascended the throne.

Under him, Old Belief suffered its most severe blow—the altars of the churches at Rogozhskoye Cemetery were sealed. The pretext for this was a report from a Nikonian informer that on January 22, 1856, about 3,000 people had prayed in the Nativity Cathedral.

Metropolitan Philaret intervened. He submitted a petition to St. Petersburg, stating:

— To support schism at Rogozhskoye Cemetery is to support it even to the farthest reaches of Siberia. Conversely, to weaken it at Rogozhskoye Cemetery is to weaken it everywhere.

The emperor, Alexander, liked Philaret’s reasoning. He decided to discipline the Old Believers and wrote on the petition:

— If they do not join Edinoverie, then they have no need for altars to serve in.

With the sovereign’s approval, on July 7, 1856, the police sealed the royal doors and deacon’s doors of the iconostases in the Pokrovsky and Nativity cathedrals. These Moscow shrines stood without the Divine Liturgy for nearly 50 years, until Easter 1905.

Under Alexander II, as under Nicholas I, the old faith suffered monstrous persecutions—comparable only to the days of Alexei Mikhailovich or Peter I.

In 1847, the police arrested Gerontius, the abbot of Belokrinitsky Monastery. He had come from Austria to inform Christians about Metropolitan Ambrose’s reception into the Church and to collect funds for the monastery.

By imperial decree, Gerontius was first imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, then transferred to Shlisselburg Fortress.

The elder spent 21 years in solitary confinement. Driven to madness, he was later moved to a Nikonian monastery, where he died in 1868.

For those who had committed crimes against the state Church, the government established a special prison in the city of Suzdal. It was housed in the dark and damp casemates of the ancient Spaso-Euthymius Monastery. Many Old Believers languished there.

Among them was Aphony Kochuyev, who urged the disheartened Old Believers to renew their search for a bishop. Also imprisoned was the pious layman Fyodor Zhigarev, who had brought newly consecrated chrism from Belaya Krinitsa to Rogozhskoye Cemetery in 1847.

Four bishops—Alimpius, Arkady, Gennady, and Konon—were also held there.

The Death of Metropolitan Ambrose #

(From the work “The Passing of Metropolitan Ambrose”)

The health of the metropolitan declined completely from October 15, leaving him bedridden. Yet he did not lose his remaining strength, his reason, his memory, or his gift of speech. He remained unchanged in all things.

On October 25, as he neared his departure, envoys from Russia arrived with documents for the affirmation of church matters. Though gravely ill, he carefully reviewed them and lawfully established their provisions. Unable to rise from his sickbed, he lifted himself with assistance and personally signed the ecclesiastical decrees, entrusting them to the envoys and blessing them with his final instructions.

Preparing to depart from the Church Militant to the Church Triumphant, where eternal peace reigns undisturbed, he exhorted all to firmly uphold the peace of the Church, echoing the words of Christ:

— Peace I leave with you, My peace I give unto you.

Then, overcoming the agitation of his heart, he gave his final archpastoral word to the Church and asked all Christians to pray for him.

Sitting in his bed, he blessed the envoys for their journey.

On October 30, at the eighth hour of the morning, he peacefully reposed in deep old age.

May we be found worthy to be one flock under the one true Shepherd—our Lord Jesus Christ.

The Sufferers of Suzdal #

In the second half of the 19th century, Russia experienced a flourishing of science, art, and literature. During this time, gifted scholars, composers, artists, writers, and poets brought worldwide renown to the country through their works. Many literary masterpieces were written during this period—works now known to every schoolchild.

In 1859, Ostrovsky’s play The Storm was staged for the first time in the theater. In 1862, Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons was published. In 1866, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment was released for the first time. In 1869, Tolstoy completed War and Peace. In 1876, Nekrasov finished his poem Who Lives Happily in Russia?, and in 1880, Chekhov published his first short stories.

It seemed as though the light of enlightenment had forever banished the shadows of cruelty, barbarism, and ignorance from Russia. Yet at the same time, across the country, Old Believer clergy were being unjustly and indefinitely imprisoned.

Bishop Savvatiy (Levshin) of Siberia spent six years in prison. Bishop Constantine (Korovin) of Orenburg was held in confinement for two years. The dungeons of Solovetsky Monastery remained occupied as before, with many priests, monks, and laypeople suffering there.

Old Believer clergy who fell into the hands of the authorities were put on trial. Not for crimes—not for murder or theft—but simply for refusing to submit to the Synodal Church and for preaching the old faith.

The main prison for Old Believers was the Spaso-Euthymius Monastery. In 1854, Archbishop Arkady (Dorofeev) and Bishop Alimpiy (Veprintsev) were brought there.

Arkady and Alimpiy had once taken monastic vows at the Laurentian Monastery in Vetka. Later, they were consecrated as bishops for the Old Believers of Dobruja. Arkady became the archbishop of the settlement Russian Glory, while Alimpiy became the bishop of the city of Tulcea.

In 1853, Dobruja—then under Turkish rule—was occupied by Russian troops. In 1854, Arkady and Alimpiy were arrested as “false bishops” and sent to Kiev, then to Moscow. After severe interrogations, they were placed in the Suzdal monastic prison under the supervision of an archimandrite.

The hierarchs were confined in solitary cells and stripped of their names: Arkady became Secret Prisoner No. 1, and Alimpiy—Secret Prisoner No. 2. For years, they saw no human face except for the servant who brought them food. Occasionally, the archimandrite would visit, urging them to submit to the Synodal Church. But the bishops remained steadfast and never renounced Old Belief.

In the dark and cold dungeon, the aged Alimpiy’s health declined. He passed away in 1859, remaining faithful to the old faith until the end.

That same year, another prisoner was brought to the monastery—Bishop Konon (Smirnov) of Novozybkov, who had been arrested by the police in 1858. In 1863, Bishop Gennady (Belyaev) of Perm was also imprisoned there.

The hierarchs were placed under strict surveillance. Armed guards stood by their cells, constantly watching them through special peepholes in the doors. Under such unrelenting scrutiny, even praying in peace was impossible. The prisoners were forbidden to keep paper, ink, or pens, and they were not allowed to correspond with anyone.

Although the bishops were held in the utmost secrecy, the Old Believers eventually learned of their imprisonment. Letters began to arrive in Suzdal from all over Russia. The faithful expressed sympathy for the imprisoned bishops, asked for their prayers and blessings, and sent gifts, including black caviar. All letters were inspected by the archimandrite, who kept the gifts for himself.

The hierarchs languished in prison until 1881. That year, Emperor Alexander II was killed in a bomb explosion, and his son, Alexander III, ascended the throne. By his decree, the three suffering bishops—having completely lost their health in the dark dungeons—were finally freed.

The writer Leo Tolstoy played a role in their liberation. Learning about the prisoners in the Suzdal prison, he used his influential relatives and acquaintances to petition on their behalf in St. Petersburg. It was only after a second attempt that these efforts succeeded—the bishops were released.

The tsar’s mercy was announced to the hierarchs on September 9, 1881. The next day, they left the prison forever.

Konon, who was already 84 years old, was so weak that he could not walk. He had to be carried out of his cell in the arms of others. The elderly bishop spent the rest of his life bedridden.

Bishop Konon of Novozybkovsky

Bishop Konon of Novozybkovsky

The tragic fate of the Suzdal prisoners was widely known throughout Russia. Newspapers wrote about them, Tolstoy himself defended them, and their release became a major event in public life.

Yet the fates of hundreds of Old Believer priests, deacons, and monks—who suffered in prisons and labor camps—remain less well known. A testament to their martyrdom for Christ can be found in the many letters sent to Archbishop Anthony.

Here are just two of them.

Priest Ioann Tsukanov from the village of Ploskoye was captured in December 1869 while traveling to minister to his flock. During interrogation, he declared himself a clergyman:

— Suddenly, I was bound with iron shackles. And while being chained, one of the witnesses—a Moldovan of cruel disposition—grasped my foot tightly with both hands and forcibly twisted it out of its joints. Since then, I have not dared to step on it.

His parishioners managed to secure his release on bail. From home, he wrote to the archbishop:

— I am now sick, suffering in both my legs and my entire body, and my health is completely broken. I can no longer go out to serve, for which I humbly ask Your Grace to pray for me.

Priest Savva Denisov, who served in the Don region, wrote to the archbishop in March 1873:

— Tell all of God’s chosen Christians of my imprisonment. Bring prayer to the Lord God for my affliction, that the Merciful Lord may strengthen me from above to endure the sorrows of prison, where I shed tears from my suffering.

— My imprisonment is as sorrowful as the noisy Babylon. I have no peaceful place to pray. Only the Jesus Prayer brings me comfort and gladdens my heart.

— My soul longs to be freed from these chains. The prison weighs upon me greatly, for it is filled with a perverse and wicked people.

Everyone understood that a modern world power could no longer apply the cruel laws of past centuries against those of different faiths and beliefs. The Old Believer question could no longer be resolved through imprisonment, exile, hard labor, and shackles.

Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery #

In the mid-18th century, there were no more than twenty bespopovtsy families of the Fedoseyev persuasion in the Moscow suburbs of Cherkizovo and Preobrazhenskoe. Their prayer house was located in Preobrazhenskoe.

Nearby were large brick factories owned by the wealthy merchant Ilya Alexeyevich Kovylin (also spelled Kavylin, 1731–1809). After becoming acquainted with the village residents, Kovylin decided to convert to Old Belief.

The bespopovtsy regarded the Synodal Church as a congregation of the Antichrist and did not recognize baptisms performed within it. All who joined them were re-baptized. Kovylin was no exception—he was re-baptized in 1768.

During the plague of 1771, Kovylin petitioned Catherine II for permission to establish a hospital near Preobrazhenskoe and received approval.

Alongside the hospital, almshouses and a cemetery were founded. A special place for re-baptism was arranged at a nearby pond for those wishing to join the bespopovtsy. The buildings were enclosed by crenelated walls with towers.

Thus arose the renowned Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery, which remains of great significance to Old Believers to this day.

Becoming the overseer of the hospital and almshouses, Kovylin exerted great effort in establishing an Old Believer community based on them. In 1781, he traveled to the Vyg Monastery and brought back a monastic rule for the Moscow bespopovtsy.

According to this rule, two monastic communities were established in Preobrazhenskoe—one for men and one for women. All interaction between them was strictly forbidden. Special attire was assigned to all inhabitants: men wore black caftans, while women wore black sarafans and headscarves.

By the end of the 18th century, the number of parishioners at Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery had grown to 10,000. Kovylin donated his vast fortune—300,000 rubles—for the benefit of the Old Believer community. With these funds, stone churches and monastic cells were built.

In 1784, a majestic church dedicated to the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos was constructed in the men’s monastery. In 1805, a small chapel for funeral services was erected at the cemetery. In 1811, after Kovylin’s death, the Exaltation of the Cross church in the women’s monastery was completed.

Kovylin spent money not only on the construction of churches and the establishment of almshouses but also on collecting ancient books, icons, and other artifacts of Russian antiquity.

In 1806, renovations began on the Poteshny Palace in the Kremlin—the very place where Alexei Mikhailovich’s court theater had been housed. The historic building was being adapted to modern needs, with its interior and exterior decorations being destroyed.

Kovylin managed to purchase the palace’s white-stone gates, adorned with images of lions. These Lion Gates were transported to Preobrazhenskoe and installed at the entrance of the women’s monastery. However, in 1930, they were destroyed.

A dynamic and enterprising man, Kovylin had extensive connections. He frequently visited the capital and had met Empress Catherine II, Emperor Paul I, and Emperor Alexander I on multiple occasions. In 1809, the merchant once again traveled to St. Petersburg on business for the monastery.

On his return journey to Moscow, Kovylin caught a cold and suddenly passed away on August 21, 1809. His body was buried at Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery.

To this day, the bespopovtsy reverently preserve Kovylin’s grave. Inscribed on his tombstone are the words:

— Mortal, remember that the Holy Church, or the spiritual assembly of Christians, is one body, whose head is Christ, and that any discord among Christians is an ailment of the Church that offends its Head. Therefore, strive to avoid all occasions that might inflame enmity and discord.

The writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky held Kovylin’s memory in high regard. His father, Mikhail Andreevich Dostoevsky, obtained a position as a physician at the Mariinsky Hospital—a Moscow infirmary for the poor—thanks to Kovylin’s assistance.

In June 1880, Dostoevsky traveled to Moscow for the unveiling of the Pushkin Monument. Taking the opportunity, he decided to visit Kovylin’s grave. He invited his friend Bykovsky to Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery:

— If you wish to pay your respects to the great Russian benefactor Ilya Alexeyevich Kovylin, whose remains rest at the Old Believer Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery, come to me this evening. Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev and Dmitry Vasilyevich Grigorovich are coming with me. My late father knew Kovylin personally. Thanks to his intercession, my father secured the position of doctor at the Mariinsky Hospital.

Kovylin never refused anyone in need of help. Yet this did not prevent him from adhering to bespopovtsy teachings, which held that the world was ruled by the Antichrist and that the Russian tsar was his servant. At Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery, prayers for the health of rulers were never offered, though they did not reject royal favors.

This led to the monastery coming under close police surveillance in 1847. The cemetery’s caretakers—merchants Fyodor Alexeyevich Guchkov and Konstantin Yegorovich Yegorov—were sent into exile.

Perhaps the real reason for their disgrace was the discovery that Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery was considering accepting the priesthood of the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy. When word of this reached St. Petersburg, the authorities decided to act cunningly.

Deceptive agents secretly sowed distrust of the popovtsy among the bespopovtsy. A rift developed among the leading figures of Moscow’s Old Believer community—one that greatly benefited the authorities.

After the unsuccessful attempt to receive priesthood from the Ancient Orthodox Church, the Fedoseyevtsy turned to the Synodal Church. In 1853, the sons of Guchkov and several esteemed merchants—53 parishioners of Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery in total—converted to Edinoverie.

At their request, the authorities seized the Dormition Chapel from the Old Believers. In 1854, Metropolitan Philaret consecrated the St. Nicholas Chapel there. By 1857, the entire Dormition Church, which had been rebuilt by the Guchkovs, was consecrated as an Edinoverie church.

In 1866, the men’s monastery at Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery, along with all its property, was seized by the state Church. By Philaret’s blessing, an Edinoverie men’s monastery was established there.

The bespopovtsy were left only with the women’s monastery and the Exaltation of the Cross Chapel. It was not until 1923, when the monastery was closed by the Soviet authorities, that the Old Believers managed to reclaim the eastern part of the Dormition Church.

Archbishop Anthony #

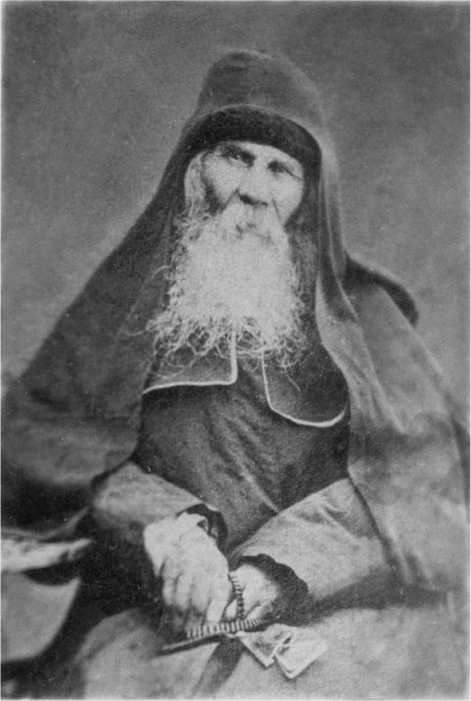

At any moment, the supreme hierarch of the Russian Old Believers, Archbishop Anthony, could have shared the fate of the suffering prisoners in Suzdal. Only the mercy of God spared him from imprisonment. Preserved by divine providence, Anthony led the Church for many years.

Andrei Illarionovich Shutov, the future archbishop, was born in the village of Nastasino, near Moscow, to a poor peasant family that belonged to the Synodal Church.

His parents were simple people and kept no chronicles or genealogies. Thus, the exact year of his birth remains unknown. Some sources suggest 1800, while others—perhaps more reliably—place it in 1812.

At the age of ten, Andrei, already literate, was sent by his parents to work in the office of a textile factory in Nastasino. After three years, he was sent to Moscow to study drawing. After two years of study, the young man returned to the factory and worked as a designer, creating patterns for fabrics.

In 1827, Andrei’s father passed away. A year later, his mother pressured him into marriage. However, in 1833, Shutov left his mother Anastasia and his wife Irina and secretly fled to the bespopovtsy-Fedoseyevtsy at the Pokrovsky Monastery.

This monastery was located in Starodub, near the settlement of Zlynka. There, Andrei was re-baptized according to the Fedoseyev teaching. He wished to take monastic vows and remain in the monastery permanently, but the strict laws of the time made this impossible.

Shutov moved to Moscow and found work in the office of the textile merchant Guchkov, who was the overseer of Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery.

In the office, Shutov advanced to the position of senior clerk, and later served as treasurer at Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery. His wife Irina, who had also converted to Old Belief, lived there until her death in 1847.

Several times, Andrei Illarionovich attempted to leave Moscow and his treasurer’s position in search of a secluded monastic life. But each time, the bespopovtsy persuaded him to return to Preobrazhenskoe Cemetery. Only in 1849 was he finally able to leave the bustle of the city and move to Pokrovsky Monastery, where he took monastic vows and was given the name Anthony.

In 1850, Anthony moved to the Old Believer Voinovsky Monastery in Prussia. A year later, he went to a skete near the village of Klimoutsy in Austria. This village, located two versts from Belaya Krinitsa, was inhabited by Fedoseyevtsy.

At Belokrinitsky Monastery, Anthony met the venerable monk Paul. They often discussed Christian priesthood and the Orthodox sacraments. These conversations convinced Anthony of the falsehood of bespopovstvo, and he desired to join the Church.

When the residents of Klimoutsy learned of this, they attacked Anthony, stripped him of his clothes and shoes, and harshly rebuked him for abandoning their faith. They locked him in a cell wearing only a shirt and kept him under guard for at least five weeks.

Despite this, Anthony managed to escape from Klimoutsy and flee to Belokrinitsky Monastery. In February 1852, he was received into the Church, tonsured anew, and blessed to bake bread for the brethren.

A year later, on February 3, 1853, Metropolitan Cyril consecrated him as a bishop. Anthony became Archbishop of Vladimir.

Fearing arrest, the archbishop returned to his homeland. All Russian Old Believer clergy recognized him as their supreme pastor.

The saint’s tireless labors for the Church soon drew the attention of the imperial government. A warrant was issued for his arrest. A massive reward of 12,000 rubles was promised for his capture. This led to an influx of detectives who abandoned all other tasks and focused solely on apprehending Anthony.

The archbishop had to go into hiding, dressing as a peasant, sleeping in haylofts and attics. Many times, he was surrounded by police, detectives, and Cossacks. But each time, by some miracle, he evaded capture. His ingenuity was remarkable.

Archbishop Anthony and Deacon Varlaam

Archbishop Anthony and Deacon Varlaam

For example, when pursued, the saint would soak a handkerchief in vodka and place it in his pocket. When detectives caught up with him, he would take out the handkerchief and rub it on his face. Smelling the strong scent of alcohol, the detectives doubted that he was their target. Pretending to be drunk, Anthony would then slip away.

While constantly on the move, the archbishop continued to ordain clergy, tonsure monks, consecrate portable churches, and bless secret house chapels. In the early years of his episcopacy alone, he ordained 54 priests.

In 1863, the Church Council elected Anthony Archbishop of Moscow and All Russia.

The saint was an avid collector of spiritually edifying books, distributing them to bishops, zealous priests, and pious laypeople. He donated many manuscripts and publications to monasteries. But Anthony gave more than just books—he adorned many churches with icons.

To clergy who had been imprisoned or exiled, the archbishop sent alms and petitioned the authorities for their release through trusted intermediaries. Orphans left destitute by deceased priests were placed in good homes where they could be provided for. Anthony also aided priests’ widows and aging or retired clergymen.

Despite his constant concern for the Church and the daily expectation of arrest, the archbishop rigorously adhered to his monastic vows. He prayed fervently every day and fasted so strictly that he abstained not only from alcohol but even from drinking warm water. Even in illness, he never abandoned the divine services.

After serving approximately one hundred liturgies in succession, on the night of November 2–3, 1881, Anthony experienced severe chest pains, from which he had long suffered.

Realizing that death was near, the archbishop began issuing final instructions regarding all ongoing matters.

His cell attendant said to him:

— Why, Vladyka, are you giving orders as if everything is final? Perhaps the Lord will restore your health, and then you will see these matters through yourself.

But the archbishop replied:

— No, I dare not ask God for this now. When I was seriously ill before, I prayed for two more years of life. In His mercy, He granted me five. I must be content with this.

After several days of illness, the saint peacefully reposed on November 8, 1881, in his modest dwelling in Moscow.

On November 10, he was buried at Rogozhskoye Cemetery in the presence of a vast multitude of people.

The Chapel Concord #

In the early 18th century, under Peter I, when life was especially difficult for the Old Believers, bespopovtsy preachers taught that the Russian kingdom—and the entire world—had fallen under the rule of the Antichrist.

In the Volga region, this message was spread by Kozma Andreev and Kozma Panfilov, peasants from Kerzhenets. Their teaching was simple. They claimed:

— The grace of God is no longer found in churches, nor in reading, nor in singing, nor in icons, nor in any object. Everything has been taken up to heaven.

Both preachers were captured and died under torture.

Their followers formed a distinct movement within bespopovstvo—the Netovtsy (Nets Agreement). The name derives from the word net (“no”), since, according to their doctrine, there is no longer a true Church, no true priesthood, and no true worship left in the world.

The Netovtsy were sometimes called Spasovtsy (Savior’s Concord), as they placed all their hope in Christ the Savior, saying:

— The Merciful Savior alone knows how to save us.

In Novgorod and Pskov, Feodosiy Vasilyev preached about the reign of the Antichrist. He taught:

— Because of our sins, the Antichrist now rules the world, reigning spiritually in the visible Church. He has destroyed all its sacraments and darkened every sacred thing.

This fearful preaching spread beyond the Ural Mountains and into Siberia, unsettling the minds of simple Christians. Many began to say, referring to Tsar Peter:

— Here he is, the Antichrist, the devil’s devoted servant, the merciless persecutor of believers. Here are the last days. Persecution and executions are everywhere. The blood of Christians flows in rivers across the Russian land. The end of the world is near!

To many, the signs of the impending apocalypse seemed undeniable—such as the brutal destruction of the Kerzhenets sketes by the authorities in 1719.

Tens of thousands of Christians fled from the Volga to the Urals, the Altai, and Siberia. There, they mingled with local Old Believers, giving rise to a unique form of Old Belief in Trans-Urals, which combined elements of both popovstvo and bespopovstvo.

Old Believers living in settlements and working in factories leaned more toward popovstvo, while those in rural villages engaged in farming tended toward bespopovstvo.

This was largely due to the scarcity of devout clergy. There were too few priests to meet the spiritual needs of all believers, especially those living in remote countryside areas.

Thus, in 1723, a council was held in the village of Kirsanova on the Iryum River, which allowed laypeople, in cases where a worthy priest could not be found, to baptize infants themselves and perform marriages with parental blessings.

Among the refugees from Kerzhenets was the hieromonk Nikifor. He first lived in the Urals and later settled on the Yaik River. Through his blessing, the Old Believers accepted Semen Klyucharev, the first “runaway priest” in those regions.

Several other priests were later received by the Old Believers. They were highly respected. However, in 1754, the last of them, Jacob, died in Nevyansk. For the first time, the faithful were left without priests.

They feared accepting priests from Vetka and Starodub, suspecting that some of them might have been baptized by sprinkling rather than immersion. Or perhaps the bishop who ordained them had himself been baptized improperly.

For several years, the Old Believers managed without clergy, until they found a certain Father Peter. However, no one was available to receive him into Old Belief through confession, the renunciation of heresy, and the sacrament of Chrismation. After much deliberation, they decided to perform three molebens, after which Peter vested in priestly garments and began to serve.

After Peter’s death, the Old Believers debated where they could find priests who had undoubtedly been baptized by immersion. A rumor spread that in Georgia, baptisms were performed with triple immersion. Later, they began to say that the clergy of Ryazan met the strict requirements of Old Belief.

Thus, in the Urals, only Georgian and Ryazan priests were accepted.

The first Ryazan priest was Hieronimus, who was acknowledged as having valid succession from Father Jacob. The last priest in the Urals was Paramon Lebedev. However, in 1838, he returned to the Synodal Church.

After this, the most devout Christians traveled to distant places for confession, communion, and marriage, seeking out the few remaining pious priests. Some would travel 500 versts to Kazan, where a priest secretly lived in a merchant’s house.

Some communities accepted priests who had been received into Old Belief through Chrismation in the monasteries on the Irgyz River. But in 1837, under Nicholas I, these monasteries were destroyed with unprecedented cruelty.

After this, in Old Believer communities in the Urals, the Altai, and Siberia, Nicholas was declared to be the Antichrist. Once again, there was talk of the imminent end of the world.

However, after the emperor’s death, the Old Believers asked themselves: Whom should we now consider the Antichrist? Heated disputes began. The faithful split into two irreconcilable factions.

One group believed that the Antichrist had physically, visibly, taken the throne in the person of the Russian tsar. They considered all emperors and subsequent rulers of Russia to be the Antichrist, even up to the present day.

The other group argued that the Antichrist had established his reign spiritually, invisibly. To them, the entire state system—its officials, police, and soldiers—was the Antichrist.

Some communities rejected the continued acceptance of runaway priests, effectively becoming bespopovtsy. They formed a distinct movement within Old Belief known as Chapel Concord (Chasovennoe Soglasie).

The name comes from the fact that these Old Believers conducted services in chapels (chasovnya) without altars. This group was also called Starikovtsy (“Elder’s Concord”), as their worship services were led by respected lay elders.

Refusing to accept new priests, these Old Believers kept reserve Holy Gifts in their homes, consecrated by former priests, for use in communion. Baptism of children was entrusted to elders. Marriages were either performed with parental blessings or conducted in Synodal Church temples.

Initially, the Chapel Old Believers regarded their situation as unfortunate and improper. The elders, who had been baptized and married by priests, understood that their actions were unlawful and barely beneficial for the soul. They never abandoned hope of finding true priesthood and the true Church.

Thus, in the second half of the 19th century, many from the Chapel Concord accepted the priesthood of the Belokrinitskaya Hierarchy. Those who did not, over time, became fully bespopovtsy.