Wonderworkers of Shamara #

Since the time of the Schism, the Urals had become a refuge for thousands of Christians who refused to accept the reforms of Alexei Mikhailovich and Patriarch Nikon. Numerous refugees settled throughout this vast region, from the Pechora River in the north to the Yaik River in the south.

The local Old Believers engaged in farming, trade, and various crafts. They mined ore and worked in iron and steel factories, while others served in the Ural Cossack Host. In major cities such as Yekaterinburg, Kurgan, Nizhny Tagil, Orenburg, Orsk, Perm, Sterlitamak, and Ufa, large communities of both popovtsy and bespopovtsy thrived.

In the mid-19th century, two brothers—Arcady and Constantine—lived in the Urals. They were Old Believers of the Chapel Accord (Chasovennoe Soglasie) and had taken monastic vows. They came from a wealthy family, were young and well-read. In the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers, they found assurance that the Church, the priesthood, and the sacraments would remain on earth until the end of time.

Upon learning of the emergence of the Belokrinitskaya Hierarchy, the brothers decided to investigate for themselves. They undertook a long and arduous journey to Moscow, where they met Archbishop Anthony.

After speaking with the hierarch, Arcady and Constantine wished to join the Church. The archbishop ordained them as priests. After spending some time away from the Urals, the brothers returned home, bringing with them the reserve Holy Gifts for Communion.

They began preaching to their fellow countrymen about the pious clergy and the Church’s sacraments. However, their preaching only provoked hostility among their relatives and acquaintances. Eventually, the brothers left their homeland, seeking a more secluded place away from the turmoil of the world.

They settled in a dense forest near the present-day village of Platonovo, on land owned by a peasant named Guryan Ivanovich Shchukin. With his permission, Arcady and Constantine built a small hut in the woods and lived in complete solitude. They survived on berries, mushrooms, and roots, catching fish from the river. They wore heavy chains as a form of ascetic discipline and prayed without ceasing.

An elderly woman from the Shaydura hamlet accidentally discovered the hermits’ cell. The brothers begged her not to reveal their whereabouts, but she let the secret slip.

Despite their efforts to remain secluded, news of their existence spread throughout the region. Local residents began making pilgrimages to the young, learned hieromonks—some seeking advice, others a blessing, and some requesting their prayers.

Through their virtues, piety, and knowledge, Arcady and Constantine convinced many of the eternal nature of the priesthood and persuaded them to accept the Belokrinitskaya Hierarchy. Simple folk rejoiced in their presence. Others, including bespopovtsy teachers, out of envy, slandered them. They were accused of greed, with rumors spreading that they had hidden money in their cell.

The elderly woman from Shaydura occasionally visited the hieromonks. She brought them alms, confessed her sins, and received Communion.

One summer, during Apostles’ Fast in 1856, she set out once again to see them, bringing her grandson along. But when they arrived, the cell was empty. On the table lay a mysterious note:

— Seek us beneath the overturned birch tree.

Sensing trouble, the woman called for the nearby villagers. They began searching the forest.

On the feast of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, June 29 (July 12 according to the modern calendar), the remains of the two ascetics were found, covered with birch branches.

Despite the summer heat, the bodies of the hieromonks remained completely incorrupt, except for their little fingers, which had decayed—an indication that their deaths had occurred long before they were discovered. The police launched an investigation into the murder.

A doctor was summoned to perform an autopsy on Arcady and Constantine. As he easily cut through their garments, his knife scraped against the iron chains beneath. Overcome with emotion, he cast aside his knife, weeping, and declared that he refused to desecrate the relics of the saints.

The brothers were buried on a plot of land donated by the same peasant, Shchukin, on the summit of a wooded hill, not far from their cell.

Before long, the murderer was found. During the investigation, he revealed that the ascetics had suffered a martyr’s death on January 18 (January 31 according to the modern calendar) in 1856, meaning their incorrupt bodies had remained untouched for half a year before being discovered.

During his trial, the criminal confessed that he had been convinced by the bespopovtsy teachers that the hermits had hidden great riches in their hut:

— I thought they had gold!

As he killed one of the monks, the other did not resist but only prayed:

— Lord, my brother is being slain. Soon I, too, shall be killed. Forgive us, O Lord!

That year, the winter had been harsh. The ground was so deeply frozen that digging a grave was impossible. Instead, the murderer covered Arcady and Constantine with snow and dry birch branches.

The miraculous preservation of their bodies for months astounded the local people, leading many bespopovtsy, who had previously rejected the priesthood, to join the Church.

From this time, the veneration of the ascetics as holy servants of God began. Soon, a spring emerged beside their grave. Residents of nearby villages and hamlets often reported seeing two candles burning at the burial site during the night—Arcady and Constantine continued to pray for humanity.

Pilgrims began flocking to their grave—not only popovtsy, but even bespopovtsy and Nikonians. Through the prayers of the saintly ascetics, numerous miraculous healings were reported.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the bespopovtsy exhumed the hieromonks’ grave to examine their remains. The bodies were still incorrupt! After witnessing this, many bespopovtsy joined the Church, including three of their nastavniks (elders). Two of them later became priests themselves.

In 1923, Soviet atheists desecrated the grave. Once again, the bodies of Arcady and Constantine were found to be untouched! In their sacrilegious outrage, the desecrators defiled the relics. After this, the incorrupt bodies finally began to decay, and the miraculous spring lost much of its former flow.

In May 1996, when Metropolitan Alimpiy (Gusev) visited the hermits’ grave, a new examination of the relics was conducted. Their remains had been reduced to bones, and the chains they had worn were found in the form of a rusted iron belt. At that time, part of the relics were placed in a new coffin and reburied in their original location. Another portion was placed in a reliquary and transferred to the village of Shamary, to the Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist.

In October 2005, a Church Council officially declared the veneration of Saints Arcady and Constantine to be observed throughout Russia. Today, prayers to them are offered across the country.

A Description of a Bespopovtsy Prayer House #

(From the book by F. V. Gladkov, “A Tale of Childhood”)

Behind our yard, not far from the ravine, stood the molennaya—a five-walled wooden house with a shingled roof, crowned with an eight-pointed cross at the ridge. A tall porch with carved wooden pillars led to the entrance. The pine logs and shingles on the roof and porch had turned a bluish-gray from years of rain.

The house always stood with its iron shutters closed. Once painted green, they had rusted over time.

Every Saturday, the shutters would open, and smoke would billow from the chimney, which was topped with an ornate tin cupola. The young women would go in and out with buckets and rags, pouring out dirty water into the ravine. On Sundays, the molennaya gazed out across the meadow with its pale-green windows. But on blue Saturday evenings, bright clusters of candlelight could be seen through the windows from afar.

The prayer house was built like a simple village hut—wide and spacious, with a small entryway where worshippers left their coats, and a bright, high-ceilinged prayer hall that could hold up to a hundred people. Along the side walls stood wooden benches, while the front wall was completely covered with ancient icons and large, cast-bronze eight-pointed crosses. At the center stood a grand Deisis icon, a sacred relic two hundred years old, passed down from generation to generation.

All the icons, both large and small, were of ancient origin, and the books were from the “pure” printings of pre-Nikonian times. These books, with their thick wooden covers bound in leather and filled with colorful bookmarks, lay on special shelves in the front corners.

There were no banners, no decorations on the icons or the walls—such frivolous “playthings” of ornamentation were only found in the Nikonian temple, which had fallen into papist heresy. Here, everything was austere, simple, and strict, like in a skete.

The men, dressed in gray tunics, stood at the front. The women, clad in dark sarafans and black headscarves with paisley borders, stood at the back. The children, watched over by the women, clustered behind them. They were only allowed to step outside during the service if they became tired or misbehaved—whispering, nudging each other, or stifling giggles. In such cases, they were led out of the molennaya as punishment, like mischievous troublemakers.

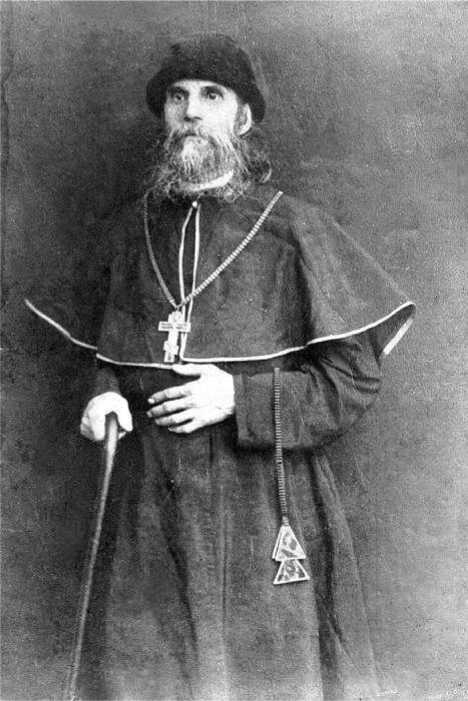

Bishop Constantine #

Lying is one of the most disgraceful sins. Yet at the same time, it is one of the most widespread. Sadly, people lie often and about many things—both great and small.

Everyone lies, but Christians must not. For the Gospel tells us that the father of lies is the devil:

“He that is of the devil, his lusts will he do.” (John 8:44)

Alas, even among Christians, this shameful sin is common. Yet there is no sin that cannot be cleansed through repentance, tears, prayer, and fasting. A true example of repentance is Bishop Constantine.

The future hierarch, Kozma Sergeyevich Korovin, was born in 1816 at the Verkhnetagil Plant, into a family of Old Believers.

His father was a wealthy man and an influential figure at the plant. Because of this, Kozma was spared from hard labor. However, from childhood, he suffered from poor health. He grew up a quiet and sickly boy.

Korovin received a good education. In his youth, he worked as a clerk at the factory office. In his spare time, he devoted himself to reading, copying, and binding church books.

He was an intelligent and well-read Christian, inclined toward solitude and contemplation. He never married and lived in a separate cell within his parents’ home until his death.

Through his piety and knowledge, Korovin drew the attention of Bishop Gennady of Perm. In 1859, Gennady tonsured Kozma into monasticism, giving him the name Constantine, and ordained him a priest. Thus, the name Hieromonk Constantine entered the annals of the Russian Church.

In one of the rooms of his family’s house, he arranged a molennaya (prayer room), where he secretly conducted services attended by neighbors.

Meanwhile, the authorities had begun a nationwide crackdown on Old Believer clergy. On the feast of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, December 6, 1862, Bishop Gennady was arrested in the house of the merchant Chuvakov in Yekaterinburg.

During these same days, significant events were unfolding at the Miass Plant. There, Bishop Paphnutius (Shikin) of Kazan had arrived, entrusted by the Church leadership with the task of consecrating two hieromonks as bishops.

On December 6, 1862, the first to be consecrated was Savvaty, the future Archbishop of Moscow. Two days later, on December 8, Paphnutius and Savvaty consecrated Constantine, the recluse of Verkhny Tagil.

Savvaty was assigned to oversee the Old Believer communities in Siberia, while Constantine was appointed to the parishes around Orenburg. However, due to his weak health, he was unable to travel to his diocese and instead returned home.

Soon, the police began hunting for Bishop Constantine. The first close call came on March 15, 1864. On that day, he and his assistant, Archimandrite Vincent (Nosov), were celebrating the Divine Liturgy in the home of the merchant Chausov in the Nizhnetagil Plant.

Constantine managed to leave before the police arrived. However, Vincent was captured.

The officers mistook Vincent for the bishop and sent him to prison in Perm. Meanwhile, the real hierarch fled to Verkhny Tagil. There, on May 3, 1864, he was finally apprehended.

The capture of Constantine was carried out with all the tactics of an expert hunting expedition. First, a Nikonian priest reported to the authorities that the Old Believer bishop was hiding in his own home. Then, an informant was sent to confirm the bishop’s presence in his cell.

A heavily armed detachment was dispatched to Verkhny Tagil. All roads leading out of the village were blocked, and ambushes were set along the paths.

Early in the morning of May 3, police officers, soldiers, and Cossacks surrounded the Korovin household. The commotion awakened the bishop’s sisters. Looking out the window and seeing the gathered crowd, they immediately realized that something was wrong.

The Cossacks pounded on the gate, demanding to be let in. But the sisters refused to open it. Then the Cossacks propped a ladder against the fence and climbed over into the courtyard.

Hearing voices outside and unaware of what was happening, Constantine stepped outside. He froze in shock at the sight of the police. They pushed past him into his cell and began a search. Then they moved on to inspect the house, the molennaya, the cellar, and the outbuildings.

Among Constantine’s belongings, they found letters in which he was addressed as a bishop. The authorities placed him under arrest and transported him, via Yekaterinburg, to Perm. He remained in prison for two years while the investigation was underway.

During interrogations, Constantine faltered in fear and denied his status, claiming that he was merely a layman. However, the letters seized during the search were presented to him as evidence. Moreover, Archimandrite Vincent identified him as a bishop during a face-to-face confrontation.

Constantine’s weakness became known to other Old Believer bishops, who wrote to him, urging him not to renounce his episcopal dignity before the authorities.

He was finally released in June 1866, but only after being forced to sign a declaration stating that he would no longer call himself a bishop. A year later, his case was officially closed. In November 1867, the court found him guilty of operating a molennaya but dismissed further punishment.

The weight of his conscience tormented Constantine. He wrote to Archbishop Anthony, confessing his great sin—the renunciation of his episcopal office. Anthony granted him absolution.

Yet the time in prison had crushed Constantine’s will. He withdrew completely from all Church matters. However, the ecclesiastical leadership insisted that he resume his pastoral duties. By the mid-1870s, Constantine once again took up his role in serving the Church.

Life in Verkhny Tagil was difficult for the bishop. He was unable to leave his home, as he remained under constant surveillance by both the police and the Nikonian clergy. Therefore, he had to carry out his ecclesiastical duties with the utmost caution.

On September 18, 1881, Constantine passed away, having taken the Great Schema shortly before his death.

From Yekaterinburg, Priest John Popov and Hieromonk Tryphilius (Bukhalov) arrived for the funeral. However, Tryphilius harbored ill feelings toward the deceased, believing that Constantine, by refusing to acknowledge himself as a bishop, had effectively renounced his episcopal office.

By the time John and Tryphilius reached Verkhny Tagil, the bishop’s body had already stiffened. Tryphilius insisted that Constantine should be buried as a simple monk. But the gathered faithful pleaded for him to be laid to rest as a bishop.

At last, according to Church custom, Tryphilius proceeded to vest the deceased in episcopal garments.

Then a miracle occurred. The rigid limbs of Constantine’s body suddenly became soft and flexible, as if he were still alive.

The sight overwhelmed Tryphilius. He wept in repentance for his hostility toward the departed and kept repeating:

— The man is alive!

Bishop Constantine was buried in the Old Believer cemetery in Verkhny Tagil. A wooden cross was placed over his grave, along with a stone slab. A century ago, his resting place was still visible.

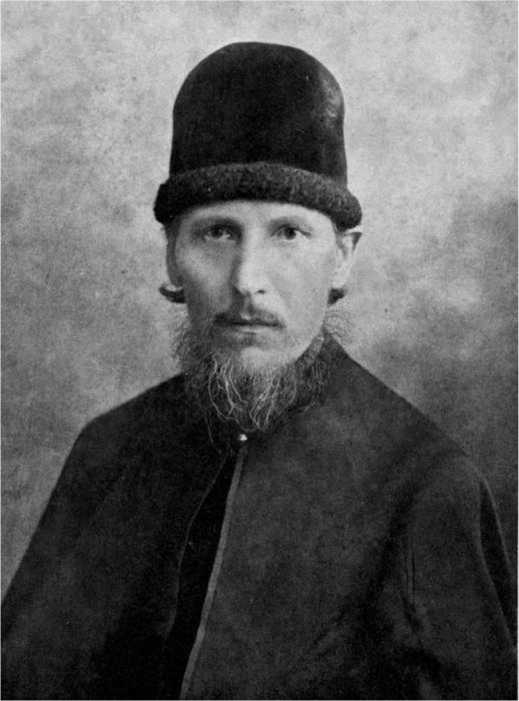

Serapion of Cheremshan #

Mother Volga, our great river, unites many cities, renowned not only in the history of the Russian state but also in the history of the Russian Church.

All along the river, Old Believer parishes still exist today—in Rzhev and Yaroslavl, in Kostroma and Kazan, in Samara and Saratov, in Volgograd and Astrakhan. One of the cities on the Volga is Nizhny Novgorod, which holds special significance in the history of Old Belief.

In the lower reaches of the Volga, where grain trade flourished, even small towns such as Syzran and Khvalynsk, Balakovo and Volsk were known for their large congregations and magnificent churches. From these places, the wealthiest merchants often moved to Moscow and St. Petersburg. Among them were the Old Believer Maltsev family from Balakovo, who traded across the world. It was said that they set grain prices even in London.

On the tributaries of the Volga—the Kerzhenets and Irgiz—stood famous monasteries and hermitages. The successors of the Irgiz monastic communities were the cloisters on the Cheremshan River near the city of Khvalynsk, nestled at the foot of picturesque hills in an area abundant with healing springs.

The great ascetic and man of prayer, Venerable Serapion, was called the “Sun of Cheremshan.”

Semyon Ivanovich Abachin, the future saint, was born in 1823 in the Nizhny Novgorod village of Murashkino, near Grigorovo—the birthplace of Protopriest Avvakum. Later, his father, the merchant Ivan Ivanovich Abachin, relocated the family to Saratov.

Semyon’s inclination toward spiritual life appeared in childhood. Other boys on the street mocked him, calling him a “priest.” He would hide from them in the cellar and read church books. At the age of eighteen, Semyon left his family home and set off on a pilgrimage.

He visited Old Believer communities in Turkey and Austria. In the monastery of the village of Russkaya Slava, he took monastic vows and was given the name Serapion.

Though Old Believers lived freely abroad, the monk longed to return to his homeland. In 1862, he and several other monks resettled in Russia, on the Cheremshan River.

The elders settled on an estate seven versts from Khvalynsk, where a watermill belonged to the merchant woman Fekla Yevdokimovna Tolstikova. A secret church was established there, and Bishop Athanasius (Kulibin) of Saratov ordained Serapion as a priest.

Everyone assumed that the monks were simply mill workers, and for several years, no one disturbed them. But eventually, the local Synodal clergy discovered the existence of the hermitage and reported it to the police. A lengthy investigation began in 1865.

Only in 1873 were Tolstikova and the monks acquitted. However, they had spent several years in prison, suffering humiliating punishments. The hermits were even sentenced to public flogging. But the merchants of Khvalynsk managed to spare them from disgrace. As the shackled monks were led to the town square, where everything was prepared for the beating, a messenger arrived from St. Petersburg with an imperial decree canceling the punishment.

Serapion returned to Cheremshan and founded a new monastery. Tolstikova took monastic vows, receiving the name Felitsata, and also moved to Cheremshan, where she established a women’s monastery. From all over Russia, pious Christians seeking a righteous life began to gather there.

The local merchants donated ancient icons and books, money, and land to the monasteries. By the end of the 19th century, Cheremshan was home to several monastic communities with stone churches and cells, orchards, beehives, ponds, watermills, and windmills. The monasteries sustained themselves and the surrounding region with bread, apples, honey, and wax.

A large two-story church with a dome and a cross was built at Serapion’s monastery. However, the authorities found this unacceptable, and the dome and cross had to be removed.

Serapion was the tireless leader of Cheremshan. Celebrating the Divine Liturgy daily, he still found time for administrative matters and spiritual instruction—explaining the Bible and the writings of the Holy Fathers and defending the Old Faith. No one ever saw him idle or resting.

If any of the brethren fell ill, the abbot would leave everything to visit and comfort the ailing monk. Every day, dozens of beggars waited outside the church for the elder to emerge. No one was ever turned away without alms.

If someone took advantage of the archimandrite’s charity, and the monastery treasurer reminded him of it, Serapion would only smile and say:

— God be with him, he must need it. And when we are in need, the Lord will provide.

The abbot was gentle and kind with everyone, yet strict with himself—he wore chains of asceticism and observed a strict fast. He did not even drink tea, but only water infused with raisins. Many times, he was asked to accept the rank of bishop, but in his humility, he declined this high honor.

Gradually, the archimandrite’s health deteriorated. Yet he refused medical help, believing bodily treatment to be unnecessary for a monk. In early 1898, Serapion became gravely ill. Then he took the Great Schema. Having received anointing and partaken of Holy Communion, the ascetic peacefully departed this life on the morning of January 7, 1898.

About a thousand local residents and countless visitors gathered for his funeral. He was buried behind the altar of the monastery church, in a crypt. The air there was damp, yet Serapion’s body remained incorrupt.

In 1909, the relics of the ascetic were examined. The fabric covering them had decayed and was tearing apart. The archimandrite’s hands, which were folded on his chest, were covered with a white coating. When it was wiped away, his hands were found to be dark yellow in color. His legs, sides, and chest appeared the same.

The monastery brethren kept this miracle a secret. Nevertheless, many knew about it, and many venerated Serapion as a saint of God. His holy relics could undoubtedly have become a treasure of the Russian Church, but the tragic events of 1917 prevented this.

The Soviet atheists destroyed the monastic communities on the Cheremshan. Shortly before the men’s monastery was closed, Venerable Serapion appeared in a dream to the abbot and the monks, commanding them to move his relics to another place.

They were transferred to Felitsata’s monastery and placed in a crypt. When the women’s monastery faced the threat of closure, the nuns buried the ascetic’s remains in the monastery cemetery.

In 1927, the last monastic community on the Cheremshan was shut down. The monastery buildings were repurposed as rest homes and sanatoriums. The site of the men’s monastery cemetery was sacrilegiously turned into a dance floor. The men’s monastery church was converted into a dining hall for the sanatorium.

The relics of Saint Serapion vanished without a trace.

Bishop Arseny #

In the land of Vladimir, many secret priestless Old Believers had lived since ancient times. Most of them were officially considered members of the Synodal Church. They attended its churches, married there, and baptized their children, yet at home, they prayed using pre-Nikonian books.

In 1840, a son named Anisim was born to one such secret Old Believer, the peasant Vasily Shvetsov, who lived in the village of Ilyina Gora. At first, the boy was taught literacy by elder priestless believers. Then, at the age of ten, he was sent to a state school for three years, where he excelled beyond all his classmates.

After finishing school, Anisim continued to visit the elders. He dreamed of an ascetic life and asked them for a blessing to live in a secluded cell. The elders agreed. But he could not expect his family to approve, so he decided to leave in secret. However, he did not want to depart without his parents’ blessing—he would not even drink water without it.

One day, during the hay harvest, he was sent home to return a horse. He decided to use this moment to leave for the hermits. Entering the house, he poured himself a mug of kvass, approached his mother, and said:

— Mother, bless me for Christ’s sake.

Seeing the mug in his hands, the woman answered:

— God bless you.

Anisim set down the mug and, with his parents’ blessing, left for the elders, who led him into the forest, where the young ascetic settled in an underground hut.

When his family realized he was missing, they assumed he had gone to the elders. A week passed, and he did not return. The Shvetsovs went to the elders, but they claimed not to know where Anisim was. Grieving and unaware of their son’s fate, his parents decided that he must have drowned.

A year later, the young man began to pity his family and decided to see what was happening at home. Coming to the village, he saw that his family was alive and well, then turned back.

On the way, he encountered a neighbor who recognized him. She ran to the Shvetsovs and told them she had seen Anisim. His mother ran after him, crying and shouting. But he walked on without turning back. Seeing that his mother was gasping for breath and falling behind, he took pity on her and stopped.

She caught up to her son, threw her arms around him, and sobbed:

— Come home! I will not let you go anywhere again!

Anisim begged her to let him return to the hermits. But his mother was adamant, and he returned to his family home.

When the time came for him to serve in the army, the Shvetsovs, as was common at the time, hired a “volunteer” to take Anisim’s place in exchange for a payment. However, the cost was so high that the family had to go into debt, which had to be worked off. To help repay it, Anisim took a job as a clerk for his fellow villagers, the Pershin brothers.

They lived in the town of Kovrov and were engaged in the grain and fish trade. The merchants owned a magnificent library, which Anisim was allowed to use. As he read spiritual books, he began to question the priestless doctrine that the priesthood had ceased. He started praying that God would reveal to him the true path to salvation.

One day, one of the Pershin brothers traveled to Moscow and took Anisim with him. While the merchant attended to business, the young clerk set out to find the true priesthood.

By chance, someone directed him to the residence of Archbishop Anthony. The archbishop welcomed the young man and spoke with him about the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy. The conversation made a deep impression on Anisim. When he returned to Kovrov, he was a convinced supporter of the priesthood.

The Pershin brothers noticed the change in him and tried to persuade him otherwise. They often debated, but their mother, listening to their discussions, shook her head and told her sons:

— Anisim knows more than you, and you will not defeat him.

In 1865, after working off the family’s debt to the merchants, Anisim immediately traveled to Moscow, where he was formally received into the Church by Archbishop Anthony. The archbishop offered him a position as his scribe, and Anisim accepted, living under the archbishop’s care for sixteen years.

While in Moscow, Shvetsov diligently read books, studied Greek, and improved his knowledge of Russian grammar. He despised wasting time and would often say:

— Our time is precious; to neglect it is bad, but to misuse it for evil is even worse.

Thanks to his extensive knowledge, Anisim Vasilyevich quickly rose to prominence as one of the foremost defenders of the Old Faith. His pious life earned him universal respect.

In 1881, Archbishop Anthony passed away. Then, in 1883, with the blessing of Archbishop Savvaty (Levshin), Shvetsov traveled abroad to establish a printing press, as Old Believers in Russia were prohibited from publishing books.

Upon returning to his homeland in 1885, Anisim Vasilyevich took monastic vows and was given the name Arseny. Soon after, he was ordained to the priesthood. Following the example of the ancient apostles, Hieromonk Arseny traveled extensively, preaching the Old Faith throughout Russia.

In 1897, Bishop Viktor (Lyutikov) of the Ural and Orenburg dioceses passed away. The Ural Cossacks unanimously chose Arseny as his successor. With the unanimous agreement of all bishops and the blessing of Archbishop Savvaty, Hieromonk Arseny was consecrated to the episcopate on October 24, 1897.

The new bishop had no free time. Winter and summer, day and night, he was occupied with church affairs. Each year, he traveled across his diocese, dedicating months to visiting his flock. He also devoted much effort to writing and maintaining an extensive correspondence.

In 1906, after Christians were granted freedom of religion, a printing press was established in Uralsk with the saint’s blessing. It became the first Old Believer publishing house in Russia. Specially crafted ornate initials were made for its books, making them unmistakable in appearance.

In early September 1908, the bishop fell ill. While visiting the printing press, he caught a chill, having forgotten to put on his galoshes. The next day, he took to his bed. He had been feeling unwell for some time but had fought through his illness. This time, however, he refused medical help, despite previously accepting it when needed.

Sensing that his end was near, Bishop Arseny received Holy Communion and peacefully passed away on the morning of September 10, 1908. His death was mourned by the entire Church.

After his passing, it became clear that the only wealth he had left behind was his library. There was no money. Though many pious benefactors had made donations to him, he had given everything away to struggling parishes and impoverished priests.

Having left behind no worldly wealth, Saint Arseny entrusted to us something far more valuable—his numerous writings, which serve the Church’s benefit, and the many capable disciples he nurtured.

Defenders of the Faith #

In modern times, the word “nachetchik” (a person well-versed in religious texts) may seem archaic and rigid. The dictionary defines it as “a person who has read a lot but is only superficially familiar with everything.”

Yet, just a century ago, the word “nachetchik” was spoken with pride, and many Christians considered it an honor to be called one.

This term referred to Old Believer nachetchiks, who were highly respected and influential among the faithful. Traditionally, a nachetchik was a learned man, an expert in theology, history, and church canons.

The word itself comes from “reading” and indicates that a nachetchik acquired knowledge through books and self-education. A nachetchik was expected not only to read books but to memorize them and be able to interpret them. This was essential for enlightening others and defending the faith in theological debates.

The first nachetchiks appeared among Christians in Ancient Rome. During times of persecution, many believers refused to attend pagan schools and academies. Instead, they studied the Bible independently or under the guidance of experienced teachers and engaged in debates with pagans and heretics.

These ancient nachetchiks were called “autodidacts,” a Greek word meaning “self-taught.”

All renowned theologians and scholars of early Russian Christianity were nachetchiks. In those days, there were no specialized schools for clergy—knowledge could only be obtained from books. Large libraries existed in monasteries, so most Russian nachetchiks were monks. Many people intentionally joined monasteries to receive an education and immerse themselves in sacred literature.

Among the most famous nachetchiks of Ancient Rus was Saint Gennady, Archbishop of Novgorod (who passed away in 1505). Through his efforts, the first complete Bible in the Slavonic language was compiled. Another renowned nachetchik was St. Joseph of Volokolamsk (d. 1515), who authored The Enlightener, a major work against various heresies.

All major Russian church figures of the 17th century were also nachetchiks. For example, Patriarch Nikon and Archpriest Avvakum possessed extraordinary memories and knew countless books by heart.

After the Schism, nachetchiks became unnecessary in the Synodal Church, where seminaries and academies were established to train clergy. These institutions produced missionaries—preachers tasked with combating the Old Faith. They traveled across Russia, engaging in public debates with Old Believers.

But out-arguing the Old Believers was no easy task!

Just a century ago, they had a reputation as unparalleled orators and learned scholars. These self-taught intellectuals—merchant clerks and simple peasants—could easily defeat a graduate of a theological academy in debate.

This was all thanks to nachetchik training, which the Old Believers preserved. Unable to establish schools due to government persecution, they were forced to acquire knowledge independently through books.

In villages, early education was provided by home tutors—pious elderly men and women. Children would gather at their homes to learn the alphabet and begin reading syllables. After mastering the alphabet, they moved on to the Psalter, the Book of Hours, or the Chasoslov.

In the morning, upon arriving at the teacher’s home, children would bow three times before the icons and once at the teacher’s feet before taking their seats. The bench where they sat was usually placed by a window to allow more light. As they settled in, the house filled with a cacophony of voices.

There were no formal lessons like today. Each child received an individual assignment from the teacher based on their level of progress. One memorized the alphabet, another practiced forming syllables, a third read words aloud. Some students recited psalms and prayers from books. For the lazy and disobedient, birch rods were kept at hand.

Each time a student advanced to a new book, they would bring the teacher a gift—a pot of porridge cooked in milk, wrapped in a cloth along with a small payment. The porridge was shared among the students, while the teacher kept the money and cloth.

The entire village knew: if Vanya and Masha were walking down the street carrying a pot of porridge, it meant they had mastered the alphabet and were beginning the Psalter.

As the student grew older, they could choose to continue their education independently or under the guidance of an experienced mentor—studying the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers, and the works of Old Believer theologians.

From among the common people emerged gifted defenders of Orthodoxy, whose knowledge came from books. With both words and writings, they successfully refuted the lies and slanders of Synodal missionaries. The best nachetchiks earned the respect of the people.

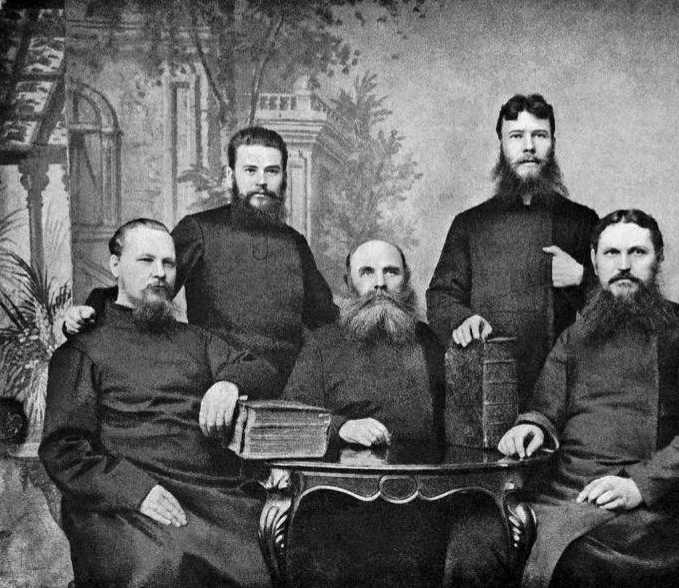

Among the most renowned nachetchiki, we must mention Bishop Arseny (Shvetsov), Illarion Georgievich Kabanov, who wrote under the name Ksenos, Mikhail Ivanovich Brilliantov, Dmitry Sergeyevich Varakin, Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin, and Kliment Anfinogenovich Peretrukhin.

The students of Arseny included nachetchiki Fyodor Melnikov and Bishop Innokenty (Usov).

For greater effectiveness, the nachetchiki held annual congresses. At their first congress in Nizhny Novgorod in 1906, a decision was made to establish the Union of Old Believer Nachetchiki.

Its purpose was to defend and spread the Old Faith, develop the activities of the nachetchiki, support them in every possible way, conduct theological discussions, and publish theological and historical books.

After 1917, through the efforts of the Soviet atheists, the tradition of nachetchestvo was eradicated. Many of these folk theologians were either killed or forced to flee Russia.

Fyodor Yefimovich Melnikov (1874–1960)—the most well-known nachetchik of our time—was among those forced into exile. From a young age, he participated in religious disputes and always emerged victorious.

After 1917, he spoke in Moscow against the Bolsheviks and atheists. He was later forced into hiding in the forests of Siberia and the mountains of the Caucasus before secretly escaping to Romania, swimming across the border river Dniester at night.

Melnikov authored numerous books on the Old Faith, including A Brief History of the Ancient Orthodox (Old Believer) Church. This book is highly recommended for anyone wishing to deepen their knowledge of Russian Orthodoxy.

In modern Russia, there are essentially no nachetchiki in the traditional sense. Most Christians who defend Old Belief today have received higher education, meaning they can no longer be considered self-taught nachetchiki in the way they once were.

Russian Merchants #

In the Russian Empire, the merchant class was composed not only of those engaged in buying and selling but also of industrialists and bankers. The prosperity and well-being of the country depended on them.

The largest entrepreneurs were Old Believers. The main wealth of Russia was concentrated in their hands. In the early 20th century, their names were widely known: the Kuznetsov family, owners of porcelain manufacturing; the Morozovs, textile magnates; and the Ryabushinskys, industrialists and bankers.

To be part of the merchant class, one had to be registered in one of three guilds. Merchants with a capital of at least 8,000 rubles were assigned to the third guild. Those with over 20,000 rubles were in the second guild. The first guild included those with over 50,000 rubles.

Entire industries and trades depended entirely on Old Believers: textile production, pottery manufacturing, grain and timber trade.

Railroads, shipping on the Volga, and oil fields in the Caspian Sea—all of these were owned by Old Believers. No major fair or industrial exhibition took place without their participation.

Old Believer industrialists never shunned technical innovations. Their factories used the most modern machinery. In 1904, Old Believer Dmitry Pavlovich Ryabushinsky (1882–1962) founded the world’s first aeronautical research institute. And in 1916, the Ryabushinsky family began construction of the Automobile Moscow Society (AMO) plant.

Old Believer merchants always remembered Christ’s words:

“Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal. But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal. For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.”

Even after amassing great wealth, merchants remained devoted children of the Ancient Orthodox Church. Wealth was never their ultimate goal. They willingly spent money on charity—almshouses, hospitals, maternity wards, orphanages, and schools.

For example, Moscow merchant of the first guild, Kozma Terentyevich Soldatenkov (1818–1901), was not only a devoted parishioner of the churches at the Rogozhskoye Cemetery but also a patron of the arts, a selfless publisher, and a generous benefactor.

He not only collected paintings by Russian artists and ancient icons but also built hospitals and almshouses in Moscow. The Soldatenkov Free Hospital for the Poor still exists today; it is now called the Botkin Hospital.

In their domestic life, merchants preserved the pious customs of their ancestors. The old-fashioned way of life of a Moscow merchant family is wonderfully depicted in Ivan Sergeyevich Shmelev’s book The Year of the Lord.

The writer’s great-grandmother, merchant Ustinya Vasilyevna Shmeleva, was an Old Believer but, during the persecutions under Nicholas I, joined the Synodal Church. However, many strict Old Believer traditions remained in the family.

In his book, Shmelev lovingly revives the image of his great-grandmother. Ustinya Vasilyevna did not eat meat for forty years, prayed day and night with a leather lestovka before an ancient reddish icon of the Crucifixion…

Those merchants who did not renounce the true faith were a firm bulwark of Orthodoxy. Their funds supported Old Believer churches, monasteries, and schools. Almost every merchant’s home had a prayer room, and sometimes a priest secretly resided there.

A description has been preserved of the molenna in the home of Moscow first-guild merchant Ivan Petrovich Butikov (1800–1874). It was arranged in the attic and had all the attributes of a proper church.

Archbishop Anthony often celebrated the Liturgy there. And he did so not only for the merchant’s family but for all Old Believers. The entrance to the house church was open to all during services.

On the western wall of the molenna, there were three windows. The eastern wall was adorned with icons. A portable church stood slightly apart from the wall—a tent made of pink damask fabric with a cross at the top, with royal doors and a northern deacon’s door made of gilded brocade with pink flowers.

On either side of the royal doors, several small icons hung from hooks. Banners stood to the right and left of the tent. In the center of the tent stood the altar, covered with pink damask fabric.

However, no matter how wealthy they were, merchants had no opportunity to openly support Old Belief. In matters of spiritual life, the rich were just as powerless as their simple brothers in faith, deprived of many freedoms.

At any time, the police and officials could storm a merchant’s home, break into the molenna, desecrate it, seize clergy, and send them to prison.

For example, on Sunday, September 5, 1865, in the home of merchantess Tolstikova on the Cheremshan River, a terrible event took place.

A Liturgy was being celebrated in the house church. The Gospel had already been read when suddenly there was a deafening crash of breaking shutters and windows. Through the shattered window, the official Vinogradov climbed into the molenna, accompanied by five policemen.

The official was drunk. Cursing, he interrupted the Liturgy. The priest begged to be allowed to finish the service, but Vinogradov entered the altar, seized the chalice with the communion wine, drank from it, and began eating the prosphora.

The priest and the faithful were horrified by such sacrilege and did not know what to do. Meanwhile, Vinogradov sat on the altar, continued swearing, and lit a cigarette from the church candles.

The official ordered the arrest of the priest and all worshippers, sending them to prison. The priest was not even allowed to remove his vestments—he was taken straight to the dungeon in full liturgical attire. Tolstikova’s molenna was ransacked by the police.

The only way to avoid such sacrilege and disgrace was bribery—a necessary but unavoidable evil.

It is known, for example, that in the late 18th century, Moscow’s Fedoseyevtsy saved the Preobrazhenskoye Cemetery from destruction with a bribe. They presented the head of the capital’s police with a pie filled with 10,000 gold rubles.

However, bribes did not always help. Not everything could be bought with money! No amount of millions could buy Old Believers the freedom to conduct worship according to pre-Nikonian books, to build churches, ring bells, publish newspapers and journals, or legally establish schools.

The long-desired freedom for Old Believers only came after the 1905 Revolution.

On Salvation in the World #

(From a letter by Hieromonk Arsenius to Priest Stefan Labzin)

Most honorable Priest Stefan Fyodorovich,

I have just now, on July 13, received your letter regarding Anna Dmitrievna’s question. You asked for a response by the 11th, but you did not indicate when you sent it. I am now in doubt whether my response has arrived in time or if it may already be unnecessary. Nevertheless, I answer just in case.

If Anna Dmitrievna has been taught by some preacher that no one in the world—not even, let’s say, a maiden—can be saved, then I cannot recognize such a teaching as pious, no matter who said it or in what book it is written.

If, on the other hand, someone tells me that one cannot escape temptations in the world, I will reply: neither can one escape them in the wilderness. If perhaps they are encountered less often there, they are all the more tormenting. But in any case, the struggle against temptations must be unceasing, both in the world and in the wilderness, until our very death. And if they drag someone into the abyss here or there, there is still a reliable lifeboat—repentance—to escape with hope in God’s mercy.

Thus, in my view, one cannot deny salvation to any person in any place. Adam was in paradise and sinned before God. Yet Lot, in Sodom—a city sinful before God—remained righteous. While seeking a more peaceful place is not without benefit, one cannot deny that salvation is possible wherever the Lord reigns.

If Anna Dmitrievna gave a vow to go to Tomsk solely because she believed she could not be saved here, then that vow is irrational. If she agrees with this and wishes to remain in her former place, read for her the prayer of absolution for her ill-considered vow and assign her a period of prostrations to the Mother of God. God will not hold her to such a vow.

But if she truly wishes to find a more suitable life for her salvation, then let it be her own decision. Do not overly restrain her freedom, regardless of how useful she may be to you. If you are worthy, God may provide another assistant, no worse than she.

Hieromonk Arsenius

July 13, 1894

Vasiliy Surikov #

The enlightened Russian of the 19th century could judge the Old Faith primarily through the works of Synodal Church writers. In these writings, Old Belief was declared “superstition,” stemming from the age-old ignorance of the Russian people.

At that time, it was customary to speak disparagingly of Old Believers, calling them “schismatics,” “bigots,” and “superstitious.” Naturally, such ignorance was deemed unworthy of the attention of high society.

However, during the reign of Nicholas I, public opinion about Old Belief began to change. A fascination with all things Russian emerged, particularly with the heritage of past centuries—ancient iconography, architecture, and literature.

Educated people turned their gaze away from contemporary Europe and toward Ancient Rus. The nobility looked closely at peasants, townsfolk, and merchants—the simple folk who had preserved the legacy of their ancestors.

Scholars explored the wondrous world of folk songs, tales, and epics. Collectors hunted for old books and icons. Among fashionable young men, beards, traditional shirts, and polished boots became popular.

Particular attention was given to Old Believers—the faithful guardians of Holy Rus’ treasures. Their manuscripts and art began to be studied seriously.

In 1861, The Life of Archpriest Avvakum was published for the first time in The Chronicles of Russian Literature and Antiquities. The following year, it was printed as a separate book.

The greatest minds of Russia became acquainted with The Life. Not everyone agreed with Avvakum’s views, but all appreciated his expressive language.

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev exclaimed:

— The Life of Archpriest Avvakum—now that is a book! Avvakum wrote in such a way that every writer should study his style. I often reread his work.

Leo Tolstoy spoke of the archpriest with great respect and affection. He read The Life aloud to his household and wept as he did so.

In the second half of the 19th century, many writers were drawn to the tragic history of the Church schism and the steadfast way of life of Old Believers. Numerous literary works were dedicated to them. Old Believers appeared in the books of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Leskov, and Mamin-Sibiryak.

Perhaps the most significant novels about Old Belief were In the Forests and On the Hills by Pavel Ivanovich Melnikov (Andrei Pechersky).

The imagery of Ancient Rus and the Old Faith was also vividly depicted in painting by artists such as Bilibin, Kustodiev, Miloradovich, Nesterov, and the Vasnetsov brothers.

But Vasily Ivanovich Surikov (1848–1916) holds a completely unique place among them.

This great Russian painter was not an Old Believer himself. However, the masterpieces he created portray history with astonishing vividness, accuracy, and truth.

Two of Surikov’s paintings are directly dedicated to Old Belief—The Morning of the Streltsy Execution and Boyarina Morozova. Both are housed in Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery.

Surikov completed The Morning of the Streltsy Execution in 1881. The painting depicts the 1698 execution of the old Moscow military corps. The Streltsy rebellion against Peter I had failed. The insurgents were condemned to death, executed by the young tsar and his henchmen.

What do we see in the painting? Red Square. St. Basil’s Cathedral. The Kremlin walls. Autumn mud. Gallows. The tsar sits on horseback, looking at the crowd with hatred.

The crowd buzzes around carts carrying the condemned. Peter’s soldiers, dressed in new European uniforms, lead the rebels to their deaths.

The Streltsy mothers, wives, and children weep as they bid farewell to their sons, husbands, and fathers. Foreigners watch with curiosity.

Among the rebels were many Old Believers. Therefore, Surikov’s painting can be considered a monument to those Christians who believed they could defend their right to pray as their fathers and grandfathers had—with the power of the sword…

In 1887, Surikov completed Boyarina Morozova. This painting brought him worldwide fame and eternal remembrance from grateful descendants.

The writer Garshin correctly observed:

— Surikov’s painting astonishingly captures this remarkable woman. Anyone who knows her tragic story, I am certain, will forever be captivated by the artist’s vision and will be unable to imagine Feodosia Prokopievna any other way than as she appears in his painting.

The foundation for Surikov’s painting was a passage from the life of Boyarynya Morozova.

After her interrogation in the Kremlin, the nun Feodora was placed on a sled and taken to prison. As they drove her past the tsar’s chambers, thinking that the sovereign was watching her disgrace from his quarters, the martyr, with the clinking of her chains, blessed herself with the sign of the cross and raised her hand towards the tsar’s windows, displaying the two-fingered sign.

A crowded street. The blue snow. The sled screeches and creaks in the frost. The people part. Men, women, children.

Right before us, sitting barefoot on the snow in rags and chains, is a holy fool. Behind him stands a wandering pilgrim, gripping his staff, his face dark with sorrow. An elderly beggar woman falls to her knees in the snowdrift. Women bow and wipe away tears with the edges of their ornate scarves. Two merchants in expensive fur coats and hats laugh spitefully.

At whom are they laughing?

At Holy Rus. At the conscience of the Russian people. At the last ray of the sun of true faith, flickering as the Moscow Tsardom fades. At the tsar’s own kinswoman, the first noblewoman, Feodosia Prokopievna Morozova.

There she sits on the sled. Her black monastic garb emphasizes the pallor of her face.

Morozova’s face is undoubtedly the most striking impression of the painting. Surikov struggled to find it. He later recounted:

— I painted the crowd first, and her afterward. And no matter how I painted her face, the crowd overpowered it. It was very difficult to find her face. I searched for a long time, but every face seemed too small—it disappeared in the crowd.

After a long search, the artist finally found the face he needed in an Old Believer woman from the Urals who had come to Moscow:

— I painted her portrait in the garden in just two hours. And as soon as I placed her in the painting—she conquered them all…

Morozova’s hands and feet are shackled. With difficulty, she raises her right hand in the two-fingered sign of the cross.

For the ancient cross, for apostolic tradition, for refusing to pray according to the new books of Patriarch Nikon, for loyalty to the ways of her ancestors, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich sends Boyarynya Morozova to prison—to cruel torture and a slow death by starvation.

And not only her. Thousands of the best people of Russia were sent to prisons and exile, tortured and executed, burned at the stake, beheaded, and hanged. Thousands suffered and perished for the unchanging Orthodoxy, for the Old Faith, for the ancient piety.

The Golden Age #

In the Russian Empire, no fewer than 15 million Old Believers lived, and according to some sources, up to a third of all Great Russians adhered to the Old Faith.

By the 19th century, the need to grant Old Believers religious freedom had become evident. In a century overshadowed by wars, conspiracies, and assassinations, Christians repeatedly demonstrated their sincere loyalty to the Russian sovereigns.

It was no coincidence that in the early 20th century, Sergei Yulyevich Witte, the head of the government at the time, wrote that Old Believers in Russia always constituted “the most loyal class to their tsar and homeland.”

One of many examples of this loyal sentiment occurred when Emperor Alexander II was assassinated on March 1, 1881. The parishioners of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery requested permission from the authorities to swear allegiance to the new sovereign. Permission was granted, and after a moleben in the Nativity Cathedral, the clergy and laity took the oath to Alexander III.

During his reign, legislation regarding Old Believers was somewhat relaxed. The law of May 3, 1883, allowed them to hold public worship services according to the pre-Nikonian books, but with severe restrictions—no bell ringing, no processions, and no clerical vestments. Old Believers were also permitted to have passports and, with the authorities’ approval, to restore their churches, something that had been prohibited since 1826.

Under this law, on May 15, 1883, the anniversary of Alexander III’s accession to the throne, a portable church was installed in the Pokrovsky Cathedral at the Rogozhskoye Cemetery, where public liturgies began to be held. However, in 1884, Moscow authorities prohibited the celebration of the liturgy in cemetery churches.

It became clear that Alexander III was not willing to grant Old Believers full religious freedom. They finally received it only after the Revolution of 1905–1907.

The revolution began with Bloody Sunday on January 9, 1905. On that day, thousands of workers in St. Petersburg marched peacefully toward the tsar’s palace to present Emperor Nicholas II with a petition regarding their grievances.

The workers carried banners and icons, with portraits of the sovereign at the front of the procession. However, Nicholas was not in St. Petersburg that day. Soldiers guarding the palace opened fire on the unarmed demonstrators. Many were killed or wounded.

All of Russia was outraged by this atrocity. It became the spark that ignited the first Russian revolution. The tsarist government, fearing the unrest sweeping across the country, quickly sought the support of the millions of Old Believers, known for their loyalty to the state.

The first sign of religious freedom came with the unsealing of the altars of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery churches, which had been locked since 1856.

On the eve of Easter, April 16, 1905, Prince Dmitry Borisovich Golitsyn, an imperial confidant, arrived at the cemetery. In the Pokrovsky Cathedral, he read aloud the tsar’s decree:

“I command that on this day, as we enter into the bright feast, the seals be removed from the altars of the Old Believer chapels at Moscow’s Rogozhskoye Cemetery, and that henceforth, the Old Believer clergy officiating there be permitted to conduct church services. May this long-awaited lifting of restrictions serve as a new expression of my trust and heartfelt goodwill toward the Old Believers, who have long been known for their unwavering loyalty to the throne. — Nicholas.”

The priests and faithful gathered in the church were overcome with emotion. In solemn silence, Golitsyn cut the seals from the altar doors. The locks were immediately broken—since the keys had long been lost.

Soon, more than 10,000 Christians gathered near the Pokrovsky Cathedral. Up to forty people worked to clean and prepare the altar for the festive service, which was celebrated with extraordinary solemnity.

The next day, on April 17, the Imperial Ukase “On the Strengthening of Religious Tolerance” was issued. It forbade the use of the term schismatics in reference to Old Believers and granted them full freedom to conduct their religious services.

However, the authorities once again made it clear to the popovtsy that they did not officially recognize the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy. The decree stated that Old Believer priests and bishops were to be referred to only as pastors and elders, though it did exempt them from military service, just as it did for the clergy of the Synodal Church.

While not a perfect law, it was nonetheless a significant milestone for Old Believers. At last, both the popovtsy and bespopovtsy could breathe freely and devote themselves to the peaceful organization of their spiritual life.

The brief period between the revolutions of 1905 and 1917 is often referred to as the Golden Age of Old Believers. Taking advantage of Nicholas II’s decree, the Old Believers, within twelve years of newfound freedom, made up for what had been lost over 250 years of persecution.

Across Russia, churches were built, schools and seminaries opened, councils and synods convened, and gramophone records of church singing were produced. Religious journals, newspapers, and liturgical books were published.

The government-sanctioned publication of Old Believer books began in earnest. A printing house was established at Rogozhskoye Cemetery, but the finest printing presses belonged to the Fedoseevtsy—one at the Preobrazhensky Cemetery in Moscow and another in the Vyatka village of Staraya Tushka.

Some of the most significant monuments to this era of religious freedom were the numerous newly built churches, often designed by renowned architects.

For instance, the famous Fyodor Shekhtel, commissioned by the Maltsev merchants, constructed a magnificent Church of the Holy Trinity in Balakovo.

With the financial support of pious benefactors, churches adorned with exquisite traditional craftsmanship were erected throughout the country.

In the northern capital, Petrograd, in 1912, the Old Believer architect Nikola Georgievich Martyanov (1872–1943) began the construction of the Pokrovsky Cathedral with its bell tower at Gromovskoye Cemetery.

This majestic church was completed and consecrated in 1915.

The Pomortsy (priestless Old Believers) of Petrograd also began constructing their own large church with a belfry in 1906—the Church of the Sign of the Most Holy Theotokos on Tverskaya Street. The construction was overseen by architect Dmitry Andreyevich Kryzhanovsky.

By 1908, the building was completed. However, in 1936, like many other churches, it was closed by the Soviet authorities.

The Old Believers of this Golden Age could not foresee the tragic fate awaiting their sacred sites. They lived a full Christian life—building churches, publishing books, and opening educational institutions. They made full use of their unexpected freedom.

Churches of Moscow #

The Old Believer community of Moscow had always been the largest and wealthiest. The ancient capital was home to the most affluent merchants, many of whom collected antique icons and books.

For example, the extensive collection of the millionaire Stepan Pavlovich Ryabushinsky (1874–1942) contained numerous icons remarkable not only for their beauty but also for their antiquity.

After religious freedom was granted, Moscow’s Old Believers began constructing churches in the ancient Russian style, adorning them with loving care. Unfortunately, many of these churches did not survive the Soviet era. Under the Bolsheviks, all of them were closed—some were repurposed, while others were demolished.

The new authorities looted the church property. Some icons found their way into museums, including the Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, and the Museum of the History of Religion. The bells were melted down, with only a few being transferred to theaters.

To this day, not all churches have been returned to their rightful owner—the Old Orthodox Church.

A monument to the unsealing of the altars of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery cathedrals was the majestic Resurrection Church-Bell Tower.

It was built in 1908–1909 by architects Fyodor Fyodorovich Gornostayev and Zinovy Ivanovich Ivanov. According to legend, the bell tower was only one brick lower than the Kremlin’s Ivan the Great.

Another commemorative church was the Assumption Cathedral near the Pokrovskaya Outpost. Construction began in 1906 under architect Nikolai Dmitrievich Polikarpov. The grand church with its bell tower was modeled after the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin.

The church was adorned with ancient icons collected from Old Believer chapels across Russia. Its iconostasis contained many Novgorod and Moscow icons from the 15th–17th centuries, as well as 16th-century royal doors.

The altar table was hewn from solid stone in the ancient manner. Church utensils—lampstands, candlesticks, and processional banners—were also crafted following traditional designs.

A silver reliquary held relics of many saints: John the Baptist, the Apostle Matthew, Nicholas the Wonderworker, Sergius of Radonezh, as well as fragments of the Lord’s Tomb and His Robe.

The church was solemnly consecrated on November 9, 1908, by Moscow Archbishop John (Kartushin). When the great multi-pood bell tolled, some worshippers wept with joy.

The Assumption Cathedral was one of the most beautiful in Russia, its grandeur and splendor rivaling the churches of the Kremlin and Rogozhskoye Cemetery. Alas, a terrible fate awaited it.

In 1935, the communists closed and desecrated the church. The ancient icons were sent to museums, while the magnificent cathedral was converted into a hideous factory dormitory.

A similarly tragic fate befell the Church of the Intercession near the German Market, which once rivaled the Assumption Cathedral in its richness of decoration.

Construction of the Intercession Church began in 1909 under the architect Ilya Yevgrafovich Bondarenko, a talented student of Shekhtel and a favorite of the Old Believers, who built several beautiful churches in Moscow and the surrounding region.

This unique two-story church was splendidly adorned with icons from Ryabushinsky’s collection. The upper church, intended for festive services, was consecrated in 1911 by Archbishop John in honor of the Intercession of the Theotokos. The lower church, designated for weekday services, was consecrated a year later in honor of the Dormition of the Theotokos.

In 1933, the Bolsheviks closed and looted the church. The most valuable icons were transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery, while the bells were given to the Bolshoi Theatre. The building was repurposed as a club and sports school.

To this day, the church remains a sports facility.

An even more tragic fate befell the Church of the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God at the Serpukhovskaya Outpost.

It was built by architect Martyanov between 1911 and 1912 on the site of a wooden chapel known since the time of Peter I. In 1930, the church was closed. The grim Soviet years, when the building served as a club and warehouse, were not its darkest days. The real disaster struck in 1991.

At a time when churches across the country were being returned to their former owners, Moscow officials sold the Old Believer church to private entrepreneurs who turned it into a tavern. In the desecrated house of God, they sold roasted chickens and vodka.

In 2003, the church was purchased by a certain Nikonian businessman. He wished to open a museum dedicated to the murdered Tsar Nicholas II. The rightful owners—the Old Believers—repeatedly petitioned for the return of their church. However, to this day, this has not happened.

The fate of other churches—St. Nicholas and the Intercession—was more fortunate. They have been returned to the Old Believers.

The Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker at the Tverskaya Outpost was built in the style of Novgorod and Pskov churches between 1914 and 1916 by architects Ivan Gavrilovich Kondratenko and Anton Mikhailovich Gurzhienko.

Due to the difficulties of wartime and the revolutionary period, the grand church with its tall bell tower was consecrated only in 1921. However, it was closed twenty years later, in January 1941.

Today, some of the icons from the church are in St. Petersburg, in the Museum of the History of Religion, while several of its bells have been transferred to the famous Church of the Great Ascension at Nikitsky Gate, where Pushkin was wed.

In 1992, the Church of St. Nicholas was returned to the faithful.

The Church of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on Ostozhenka was constructed in 1907–1908 by architects Vladimir Dmitrievich Adamovich and Vladimir Moritzovich Mayat, funded by the Ryabushinsky family.

The model for this elegant church with its bell tower was the Novgorod Church of the Savior on Nereditsa. It was adorned with 15th–17th-century icons from Ryabushinsky’s collection.

In 1938, the church was closed and plundered. Its rarest icons were transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery. It was not until 1994 that the neglected church building was returned to the Old Believers.

The Priestless Pomorian Old Believers also built their own church in Moscow.

In 1907, they laid the foundation for the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the Protection of the Theotokos. It was constructed by architect Bondarenko, who also designed the sketches for the choir stalls, iconostasis, and church furnishings.

In 1929, the Bolsheviks decided to close the church. The faithful attempted to defend it, appealing to the Moscow authorities, but in vain. In 1930, the church was closed and looted.

At various times, it housed a club, a theater, and a factory. It was not until 1993 that the desecrated building was returned to the Priestless Old Believers.