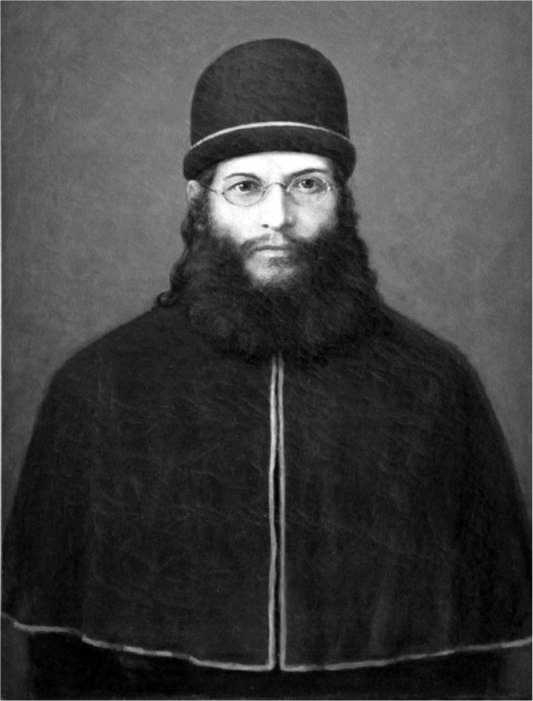

Bishop Mikhail #

From 1805, during the reign of Tsar Alexander I, even children served in the Russian army. These young soldiers were called cantonists. Typically, they were the legitimate and illegitimate sons of servicemen or the poor, as well as orphans and foundlings. They were first trained in special schools, and at the age of 18, they were sent to military service, which at the time lasted 25 years.

Under Emperor Nicholas I, Jewish and Old Believer children were forcibly conscripted into the army.

Jews were taken from 1827, and Old Believers from 1838. That year, the Tsarist government passed a law permitting the forced enlistment of Old Believer children as cantonists. This law primarily targeted the priestless Old Believers, whose marriages were not consecrated in church and were therefore considered illegitimate. Children born in such marriages were deemed illegitimate and even orphans.

During the reign of Nicholas I, a six-year-old Jewish boy was taken into the cantonist ranks. His birth name is unknown, but during his military service, he was baptized and given the Russian name Vasily Semyonov.

After completing his military service, Vasily settled in Simbirsk and married a Russian woman. In 1873, they had a son, Pavel.

Whether due to parental influence or his own choice, Pavel pursued a churchly path. He completed his studies at the Simbirsk theological school and seminary, then continued his education at the Moscow and Kazan theological academies. After completing his studies in 1899, Semyonov took monastic vows and was given the name Mikhail.

In 1900, the monk was ordained to the priesthood. That same year, Hieromonk Mikhail traveled to Istanbul for academic work. This journey left an indelible impression on him. As he studied the history of the Greek Church, he was overjoyed to visit Christian holy sites, even though they had been desecrated by Muslims.

Upon returning to Russia, he was appointed as a lecturer at the Voronezh theological seminary and later at the St. Petersburg Theological Academy. In 1902, he completed a significant study on the ecclesiastical legislation of Greek emperors, which earned him recognition in academic circles.

In 1905, Mikhail was elevated to the rank of archimandrite. Although he did not manage a monastery, the honorary title was bestowed upon him as a mark of distinction.

After the 1905 revolution, life in St. Petersburg was turbulent. Heated debates arose about Russia’s future and the state of contemporary Christianity. The whirlwind of metropolitan life drew Mikhail in.

He frequently delivered public lectures on faith, morality, and education. He could be seen in the company of prominent thinkers, scholars, writers, and poets. He himself wrote essays and articles, collaborating with numerous newspapers and journals. He even authored a play about Tsar Ivan the Terrible for the theater.

While teaching at the academy, Mikhail became disillusioned with the Synodal Church. He saw that it was not only slavishly dependent on the state but also spiritually dead. Finally, he resolved to seek the true Church—one that was free and alive.

The clergyman did not conceal his views but declared them boldly, prompting the Synod to remove him from the capital. In 1906, the dangerous dissident archimandrite was dismissed from the theological academy and exiled to a remote monastery.

In 1907, Mikhail began corresponding with Bishop Innokenty (Usov) of Nizhny Novgorod, expressing his desire to join the Old Believers. The bishop summoned him.

In October of that year, the archimandrite traveled to Nizhny Novgorod, where he was received into the Church through the sacrament of Chrismation. The Synod immediately responded by defrocking Mikhail.

The Nikonian newspapers and journals unleashed a torrent of slander and false accusations against the courageous clergyman. They even denounced his half-Jewish ancestry. The persecution of Mikhail continued until his death.

The archimandrite began collaborating with Old Believer journals such as Starobryadets (The Old Believers), Church, and Old Believer Thought, producing an astonishingly fruitful body of work. Soon, he became one of the foremost defenders of the Old Faith.

However, not everyone in the Church accepted him easily. To many, he was an enigma—too educated, too active, too trusting.

Meanwhile, a letter arrived from Canada, stating that many believers there wished to join the Old Believers. Consequently, on November 22, 1908, Innokenty consecrated Mikhail as a bishop for the future Old Believer communities in Canada.

This consecration was performed without the consent of all bishops, as required by church canons, leading to both Innokenty and Mikhail being temporarily forbidden from conducting divine services.

In August 1909, a Church Council lifted the prohibition from Innokenty. Mikhail, however, was given a choice: either travel to Canada or remain under the ban. Lacking the funds to leave, he remained barred from celebrating the liturgy.

Yet, no one forbade the bishop from writing. He continued his literary work tirelessly, despite his failing health. Most of his earnings he gave to the poor. At times, he even shared his own clothing with beggars on the streets.

Bishop Mikhail wrote many articles and books. His vivid imagination transported readers across centuries—to the catacombs of Rome, to the resplendent Constantinople, and to the Old Believer hermitages of the 18th century. His eloquent writing style was both captivating and profound.

The earthly life of the bishop was cut short suddenly.

In 1914, World War I began. The daily reports of the immense losses suffered by the Russian army, the deaths and maiming of thousands, deeply grieved him. The constant distress and relentless labor led to his exhaustion.

In 1916, Mikhail traveled from Simbirsk, where he had been living with his sister, to Moscow for medical treatment. He was robbed and beaten by unknown assailants.

On October 19, he was found on the street, unconscious, with broken ribs, and taken to a hospital for the poor.

He developed a fever. It was only a week later that he regained consciousness and was able to identify himself. The Old Believers were informed.

They transported the bishop to the hospital at the Rogozhskoye Cemetery. A priest arrived to hear his confession and administer Holy Communion. When he offered Mikhail the cross to kiss, the bishop grasped it firmly and pressed it to his lips for a long time.

The ban on the dying bishop was lifted.

The restless heart of Bishop Mikhail ceased to beat on October 27, 1916.

Three days later, he was solemnly buried at Rogozhskoye Cemetery.

The Old Believer Institute #

At the beginning of the 19th century, in addition to almshouses, the Rogozhskoye Cemetery housed an orphanage that cared for abandoned children and those from impoverished families. A school was established to educate boys, where they were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and church singing.

This school was not limited to orphans—children brought to Rogozhskoye Cemetery at a young age were also educated there. Many graduates became renowned singers in Old Believer Moscow, and some even became ecclesiastical precentors.

However, in 1835, during yet another government crackdown on the Old Faith, the cemetery school was abolished. The authorities ordered that children be returned to their parents, and orphans were sent into the cantonist ranks.

Unwilling to lose their school, the Old Believers secretly relocated it nine versts from Moscow to the village of Novinki, near Kolomenskoye. There, it continued to operate until 1839 under the local prayer house.

That same year, the school was officially shut down by government decree. But by 1840, the police discovered that the school had not been destroyed but had instead been relocated to Kolomenskoye.

In 1868, the merchant Ivan Ivanovich Shibayev opened a school in Moscow for Old Believer children. However, in 1869, the police shut it down.

In 1879, Old Believers from Moscow and St. Petersburg petitioned for permission to establish a trade school at their own expense, under government supervision. In their appeal to Emperor Alexander II, they wrote:

“We feel an extreme need for education and therefore beseech Your Majesty to grant us permission to establish our own primary and secondary schools. In these, we wish to raise our children in the fear of God and develop their abilities by teaching them the exact sciences and essential foreign languages.”

Their request was denied.

After religious freedom was granted, discussions about the necessity of Christian education were revived. This issue was actively debated at Old Believer congresses.

The congress participants insisted that education was of primary importance. They also proposed the establishment of a church school to train teachers:

“We need an Old Believer teacher or governess. We need to build a school.”

In 1911, the government finally granted permission to open the Old Believer Theological and Teacher Training Institute. A board of trustees was formed under the Rogozhskoye Cemetery community to oversee it. On September 10, 1912, the institute’s first classes began in the community building.

The board of trustees admitted 23 students without examinations. Additionally, 15 candidates were allowed to take entrance exams, of whom only 7 passed.

Among the first students, 12 were from peasant families, 6 were townsmen, 9 were Cossacks, and 13 were sons of priests. The average age of the students was 16 years.

The institute’s first director was Alexander Stepanovich Rybakov (1884–1977), a graduate of Moscow University and the father of the renowned historian Boris Alexandrovich Rybakov.

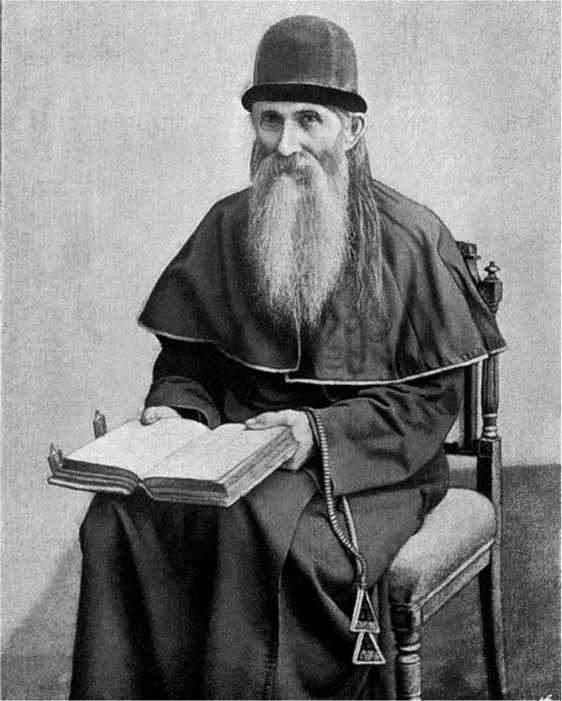

The institute’s opening was marked by a solemn prayer service led by Archbishop John. After the service, he addressed Rybakov with the hope that he would nurture strong and faithful Christians:

“Not only Moscow but all of Old Believer Russia looks to you with hope. You must produce people who understand the customs, needs, and demands of Old Believers—people of deep faith. The fate of education within Old Believers depends on this institute. If it succeeds, more institutes will open. If it fails, Old Believers will abandon the idea of higher education entirely.”

Archbishop John

Archbishop John

Thus began the institute’s work. Any young Christian could apply for admission, provided they submitted a certificate of status and class, along with a recommendation from their spiritual father or local community.

The program lasted six years. In the first four years, students studied history, Church Slavonic, Russian, Greek, and German languages, geography, mathematics, physics, Znamenny chant, and the basics of iconography. In the final two years, they studied the Bible, theology, Old Believer history, and canon law.

The educational experiment was largely successful, leading the Rogozhskoye community to allocate land for the construction of a dedicated building for the institute. In September 1915, classes began in the newly constructed facility.

The institute was associated with many prominent ecclesiastical figures of the early 20th century. Among its faculty were Bishop Michael and the talented iconographer and expert in Znamenny chant, Yakov Alekseevich Bogatenkov.

Bogatenkov’s students, trained as singers at the institute, gained wide recognition in Moscow. They were frequently invited to sing in the city’s churches. Bishop Michael authored several textbooks for the institute and parish schools, including Textbooks on the Law of God, Catechism, or a Brief Exposition of the Christian Faith, and A Study of the Liturgy.

However, the outbreak of World War I cast a shadow over the institute’s future. Many students were conscripted into the army. Nearly the entire first graduating class enrolled in military training.

In August 1917, Rybakov left Moscow. The institute’s new director was the renowned lay theologian Feodor Yefimovich Melnikov. By this time, enrollment had reached 90 students.

In September 1917, the institute was restructured into a teacher’s seminary designed to prepare students for university admission. However, in 1918, the seminary was shut down by Soviet authorities.

It would be incorrect to say that the idea of religious education died immediately after the school’s closure. Its successor was the Old Believer People’s Academy, which aimed to promote education among Old Believers and introduce the public to the Old Faith.

The academy held classes from May to July 1918. During this brief period, students attended lectures on Old Believer history, literature, and art. Some of the lecturers were Old Believers, while others were from the state (Nikonian) Church.

After the academy was shut down, all religious schools in Soviet Russia ceased to exist. The hope of theological education was extinguished for many years. Scholarly religious knowledge and theological literacy once again became the domain of a few self-taught nachetchiki (lay theologians).

However, even the need for such scholars gradually disappeared—Soviet authorities had no interest in theological nuances and actively discouraged theological studies. Debates on matters of faith ceased.

And there was no one left to debate with. Old Believer communities were fading. The churches of both the priestly and priestless Old Believers were increasingly filled with the elderly, who had little interest in theological disputes.

Are Rituals Necessary? #

(From the article of Bishop Michael)

Old Believers are most frequently accused of ritualism, that is, of stubbornly venerating ritual even more than doctrine. Their reverence for ritual is often perceived as a kind of idolatry.

But is ritual really something insignificant, something of little importance in the order of spiritual life? In another place, we have briefly written about the meaning of ritual. We have explained why Old Believers had to rise in spirit against the blasphemous encroachment upon the sacredness of ritual.

Now I wish to address primarily the Old Believer youth: what is the meaning of ritual? What is a ritual?

It is the envelope, the garment of doctrine, as we have said before. But let us now continue in a slightly different way: it is preserved spiritual life, a powerful element of Christian life, a great moment that has been frozen in time for the sake of spiritual upbringing.

The content of the baptismal rites is profound. One day, we will discuss them separately.

Consider the Paschal service, where there is the ritual of the kiss of peace. And who knows how many hearts have melted, how many angry impulses have dissolved in this ritual kiss!

On the eve of the fast, there is the ritual of forgiveness. What a mighty force of reconciliation this ritual holds within itself!

And the ritual of marriage, that is, the sacrament of matrimony in its ritual aspect—what a revelation about the family is given here to those who have ears to hear!

But how? In what way does ritual exert such an influence?

I explain it as follows. A ritual is, in its time, created by a great thought, an immense spiritual energy, a surge of loving devotion.

Yet all energy, according to the law of the conservation of spiritual energy, remains preserved. Just as warmth endures, the spiritual power of ritual remains latent within it.

There is a story by Korolenko titled Frost.

It is a fantasy. The author imagines that, sometimes, in the cold, words freeze. But then, when the sun begins to shine, he envisions how the words thaw, enter into the souls of people, and bring them a holy power.

So it is with ritual—within it are frozen words, a sacred force.

For a person who has not yet been warmed by the sun of grace, they seem dead, lifeless. Yet even for such a person, these words may awaken and come to life.

To perceive a ritual rightly, one must gaze into it, delve into its depth, so that its power may come alive in the heart.

Soviet Power #

In July 1914, the First World War began. Our country entered into conflict with Austria, Germany, and Turkey. Russia’s allies were England and France. Gradually, many countries of Europe, Asia, and America were drawn into the war, making it truly global.

The war saw the use of new and unprecedented weaponry: airplanes and tanks, mortars and machine guns, poisonous gases and explosive bullets. This resulted in heavy casualties both among the warring armies and the civilian population. Millions of people perished.

For Russia, the war became a true disaster. The tsarist troops retreated. The Germans seized our lands. The state treasury was emptied. England and France simply plundered Russia, waging war at her expense.

Russia was rapidly impoverished. Ruin and famine began to spread throughout the country. In Petrograd and Moscow, enormous queues formed for bread. The people murmured in discontent.

All of this led to the revolution of February 1917. Emperor Nicholas II abdicated the throne and was sent into exile. Power passed into the hands of the Provisional Government.

However, it was composed of weak and cowardly individuals who neither could nor wished to end the bloody war or restore order in the country. Thus, in October 1917, another revolution took place.

An armed uprising broke out in Petrograd. Power was seized by a little-known party of communist Bolsheviks. They marched under red banners, which is why they came to be called the “Reds.”

The people believed they had won. The Bolsheviks assured them that they acted in the name of workers and peasants, soldiers and sailors. The revolutionaries promised an end to the war, free transfer of land to the peasants, and factories to the workers.

All power was transferred to the Soviets—special elective institutions composed of representatives of the people. Nobles, clergy, capitalists, officials, and police officers were removed from government affairs. The communists declared them “parasites” and “bloodsuckers.”

To hasten the end of the war, on March 3, 1918, the Bolsheviks signed a peace treaty with Austria, Germany, and Turkey.

The terms of the treaty were unfavorable and disgraceful for Russia. Our country lost vast territories—Poland, Finland, the Baltic states, certain possessions in the Caucasus, and regions populated by Little Russians and Belarusians.

On the ruins of the Russian Empire, a new state arose, which came to be called Soviet Russia, and later, the Soviet Union.

The Bolsheviks did not merely destroy the great Russian state. They sought to eradicate the entire traditional way of life of the people. In 1918, Russian orthography and the Russian calendar were altered.

Several old letters were removed from our alphabet—yat (ѣ), decimal i (і), fita (ѳ), and izhitsa (ѵ). The hard sign (ъ) at the end of words after consonants was abolished.

The Julian calendar, which had been used since ancient Roman times, was replaced by the Gregorian calendar, introduced in the 16th century under Pope Gregory XIII. Today, the difference between these calendars is 13 days.

However, the Church retained the old reckoning of time. Thus, for example, the feast of the Nativity of Christ is celebrated by believers on December 25 according to the old Julian calendar, which corresponds to January 7 on the new Gregorian calendar.

Yet, the changes in spelling and timekeeping were utterly insignificant compared to other transformations that shook Russia.

The country was engulfed by a bloody wave of Red Terror. This was the name given to the Bolsheviks’ extermination of those who opposed their rule—those who were disobedient or held differing views. Beginning in 1918, the terror ebbed and flowed, but it persisted for nearly 70 years.

During these years, millions of people were senselessly and unjustly destroyed. Among the first victims was Emperor Nicholas II. He and his family were executed by gunfire in Yekaterinburg.

The communists executed, drowned, and hanged not only the tsar’s generals, prominent scholars, former officials, and merchants. They also put to death ordinary people—the very workers and peasants for whom the revolution had supposedly been carried out.

The Bolsheviks declared that one of their most important tasks was the fight against religion—the faith in God. They claimed that religion had been invented by the rich to deceive the poor and force them to work for their benefit.

Thus, all clergy were declared accomplices of the tsar and enemies of the people. Persecution was unleashed against all believers—both those who accepted priests and those who did not, Nikonian and Latin Christians, Muslims and Jews alike.

The cruelty of the Bolsheviks and their betrayal of Great Russia provoked universal outrage. The White Army rose against the Reds—a military force that sought to restore the old order and revive the former Russia.

The Civil War began. It engulfed the entire country—the Far East, Siberia, the Urals, Central Asia, the Volga region, the Don, the Caucasus, and the Black Sea coast.

Most Old Believers supported the White Army. Even Archbishop Meletiy (Kartushin), who had been elected head of the Russian Church in 1915, left Moscow and joined the rebel Cossacks on the Don.

But the war against the communists was lost by the White Army. Its generals, soldiers, and officers were forced to leave Russia forever. Along with them, many Old Believers—both clergy and laypeople—fled into exile. Some went to Romania, Yugoslavia, and France, while others journeyed to China, and from there to Australia and America.

For the millions of Old Believers who remained in Russia, dark days began.

The Church suffered terribly under the Red Terror. The stronghold of Old Belief was destroyed—wealthy industrialists and merchants, prosperous peasant kulaks, and free Cossacks were wiped out. During the years of Soviet rule, thousands of zealous clergy and pious laypeople were executed. All Old Believer monasteries were closed, plundered, and destroyed, along with hundreds of churches.

The Bolsheviks succeeded in ravaging Rogozhskoye Cemetery—something even the tsarist authorities had failed to accomplish.

In 1929, services were halted in the Nativity Cathedral. The church was looted and repurposed as a dining hall for workers. Now, instead of devout worshippers, foul-mouthed drunkards could be seen near it.

There were plans to close and convert the Intercession Cathedral into a theater, but it miraculously survived. In 1930, the bells were removed from the Resurrection Church-bell tower. Three years later, even this church was shut down.

Archbishop Meletiy #

After the passing of Archbishop Anthony, Savvaty (1824–1898), Bishop of Tobolsk and all Siberia, was elected to the Moscow episcopal see. In October 1882, the council of bishops elevated him to a higher rank—archbishop.

In August 1897, Savvaty was forced to sign a pledge with the police stating that he would no longer call himself the Archbishop of Moscow. This caused great concern among the faithful.

In December, the issue of the pledge was discussed at a gathering of the parishioners of Rogozhskoye Cemetery. The assembly decided to ask Savvaty to refer this difficult matter to the consideration of all the bishops.

In March 1898, an episcopal council was held in Nizhny Novgorod. At the council, Savvaty, having laid down his episcopal rank, was sent into retirement. In December of the same year, the new Archbishop of Moscow was elected—John (Kartushin), Bishop of the Don.

Bishop John (1837–1915) was born into a Cossack family on the Don. Even in his youth, he gained renown as an unparalleled master of theological debate. Many times, he had to engage in religious disputes with the Nikonians, including his younger brother Kalina Kartushin, who left the Old Believers and joined the Synodal Church.

Bishop John led the Ancient Orthodox Church during its flourishing years—the era of the “Golden Age.” But in 1915, the archbishop passed away.

Bishop Meletiy (Kartushin), Bishop of Saratov and Astrakhan, a cousin of the late hierarch, was elected to the Moscow see.

The future hierarch, Mikhail Polikarpovich Kartushin, was born in 1859 in a Cossack stanitsa on the Don. From a young age, he was highly respected by his fellow countrymen. At their persistent request, in 1886, Mikhail was ordained to the priesthood.

Church rules prohibit clergy from taking up arms and serving in the military. However, in the Russian Empire, the clerical ranks of the Old Believers were not officially recognized. Therefore, the young priest was subject to conscription, like all Cossacks. Before long, he was called up for military training.

One of the officers, upon learning that there was an Old Believer priest in the camp, reported it to the ataman. The ataman wished to see Kartushin. Father Mikhail appeared and honestly explained his difficult situation to his superiors.

The priest’s candor moved the ataman, who promised to send him back to his parish as soon as possible. And so it happened—the priest was released home ahead of schedule.

In 1895, Kartushin was widowed. In 1904, a church council decided to ask Mikhail to accept the episcopal rank to oversee the many parishes of the Lower Volga—Saratov and Astrakhan.

However, only in December 1908 did the widowed priest take monastic vows under the name Meletiy. That same year, he was consecrated a bishop.

In the spring of 1914, Bishop Meletiy, together with Bishop Alexander (Bogatenkov), undertook a two-month journey through the Christian East. The hierarchs visited Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and Constantinople-Istanbul.

In July 1914, war broke out. Bloody battles took place in Bukovina, forcing the White Krinitsa Metropolitan Macarius (Lobov) to flee to Moscow. The hierarch barely survived the suffering and hardships he endured.

When the war began, the Austrians, who then controlled Bukovina, accused the metropolitan of aiding the Russians. He was seized and taken to the town of Radautz. Macarius was locked in a barracks and interrogated harshly for several days.

One day, the hierarch was placed in an empty cart and left in the barracks courtyard. For several hours, a crowd of soldiers and locals mocked Macarius. They spat in his face, brandished their fists and sticks at him, and shouted:

— Judas! Traitor! Pharisee!

After yet another interrogation, the Austrians allowed the metropolitan to return to the White Krinitsa Monastery. However, they did not leave him in peace. Soldiers frequently came to the monastery for searches. Shaking their weapons, they shouted:

— Where are the Muscovites? Bring us the Muscovites!

The Austrians searched for Russian soldiers everywhere—in the bishop’s chambers, in the monks’ cells, in the churches, and in the bell tower.

Russian troops managed to occupy Bukovina briefly. Taking advantage of the opportunity, Metropolitan Macarius fled to Moscow. Around the same time—on April 24, 1915—Archbishop John passed away.

The Russian Old Believers proposed that Metropolitan Macarius take the vacant episcopal see and at the same time permanently transfer the residence of the Old Believer metropolitans from White Krinitsa to Moscow. But Macarius refused.

The Church Council elected Bishop Meletiy as Archbishop of Moscow and decided to elevate him to metropolitan status. However, due to the difficulties of wartime, this did not happen.

Then came the revolutionary year of 1917, followed by the Civil War.

In February 1918, the Soviet government issued a special law—the Decree on Freedom of Conscience. According to it, the teaching of religious foundations was prohibited in all educational institutions. Religious organizations were deprived of the right to own property. All their assets were declared the property of the people.

Archbishop Meletiy immediately addressed his flock with an appeal against the new law. The hierarch wrote:

“Under the guise of this decree, the enemies of Christianity, who now largely steer the ship of state, may with impunity commit any sacrilege against Christianity and its sanctities. Even the most ruthless foes of religion and Christianity could not have devised a law more grievous for the Church of Christ. This is not a decree on freedom of conscience, but a satanic mockery of the believing soul of the Russian people.”

Entering into open opposition with the Bolsheviks, the archbishop was forced to leave Moscow and go to the Don, which was then held by the White Army. Only at the end of 1922 did Meletiy return to the capital.

By this time, the Soviet authorities had devastated Rogozhskoye Cemetery. Its buildings and much of its property were confiscated. The Bolsheviks stripped the icons of their silver covers and precious stones. The once-rich library was transferred to state collections.

Upon his return, Meletiy had nowhere to live. He settled in the watchman’s hut by the Dormition Cathedral at Pokrovskaya Zastava. There was no money to hire a secretary, so the elderly archbishop had to handle all church correspondence himself, spending 16–18 hours a day on it.

Little is known about the final years of the hierarch’s life. He passed away on June 4, 1934, and was buried at Rogozhskoye Cemetery under a simple wooden cross.

Metropolitan Innokenty #

Literacy, erudition, and a love for books always distinguished Old Believers from members of the state Church. At a time when the Synod issued decrees prohibiting the marriage of young men and women who did not know the Our Father, the Old Believers were familiar with the entire liturgical cycle of the Church.

The Psalter and the Chasoslov (Book of Hours) could be found in every Christian home, but reading was not limited to prayer books alone. Old Believers cherished the teachings of the Holy Fathers—especially John Chrysostom and Ephraim the Syrian—as well as various lives of saints, parables, and chronicles.

Many believers owned extensive libraries, collecting ancient manuscripts and printed books. Their love of reading and the constant need to defend their convictions turned Old Believers into nachetchiks—scholars well-versed in ecclesiastical literature.

However, in debates with Synodal missionaries trained in the European manner, knowledge of Church books alone was insufficient. The best nachetchiks followed scientific developments, studied ancient manuscripts, and kept up with contemporary historical research.

One of the most outstanding nachetchiks of the early 20th century was Ivan Grigoryevich Usov, a man of vast knowledge and exceptional intellect.

He was born on January 23, 1870, in the Old Believer settlement of Svyatsk. His father, Grigory Lazarevich Usov, was a builder of windmills and provided his son with a good education.

From childhood, Ivan displayed great curiosity and an extraordinary memory. At the age of 11, his parents enrolled him in primary school, which he successfully completed.

The school principal insisted that Ivan continue his education, but his father disagreed. Instead, he sent his son to learn iconography. Nevertheless, the young man continued his studies independently, eagerly devouring books.

Before long, the young iconographer met Hieromonk Arseny. In September 1890, Arseny was arrested by the police while on a preaching mission in Starodub.

He was imprisoned in the town of Surazh under the strictest supervision, treated as a dangerous criminal.

The hieromonk was released on bail only in April 1891.

While awaiting trial, Arseny settled in an Old Believer monastery near Klintsy. There, young men eager for knowledge—including the future renowned nachetchiks Ivan Usov and Fyodor Melnikov—came to study under him.

Meeting this devoted defender of the Old Faith left a deep impression on the young men. They resolved to become equally steadfast defenders and tireless preachers of Orthodoxy.

However, Usov was soon conscripted into military service, delaying his mission. Upon completing his service in 1895, he immediately went to Arseny, settled with him, and became his devoted disciple. Under Arseny’s guidance, he began writing his first book against the missionaries, Analysis of Answers to 105 Questions, which he completed in 1896.

Usov went on to write many works defending the Old Faith and soon became one of its most prominent nachetchiks. He traveled across nearly all of Russia, successfully debating the Nikonians.

In 1902, Ivan Grigoryevich took monastic vows and was given the name Innokenty. That same year, he was elected bishop for Nizhny Novgorod and Kostroma. A year later, he was consecrated to the episcopacy.

Innokenty was the youngest Russian bishop. After the Old Believers were granted freedom of religion, he became a pioneer in new initiatives and projects. He founded the first monthly Christian journal, The Old Believer Herald, and was among the first to focus on training teachers for parish schools.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Innokenty boldly and openly opposed the godless Bolsheviks. He composed a prayer for the deliverance of Russia, which included the following supplication to God:

“Preserve Thy world from the ruin of militant atheism. Deliver the Russian land from Thine enemies, who torment and slaughter countless innocent people, and above all, those who believe in Thee. Grant rest in Thy kingdom to all who have been tortured to death by weapons and gunfire, by hunger, frost, and other means of destruction at the hands of the devil’s inhuman servants. Take up Thy shield and sword and arise to help us. Stretch forth Thine arm from the heights of Thy glory, strengthen our will and power to strike down and overthrow the wicked enemies of mankind. And free our land from the heavy yoke of the hateful rule of the godless.”

For such actions, the archbishop faced the threat of severe reprisal from the communists. In 1920, he was forced to flee to Moldova, which had been annexed to Romania. The Church authorities assigned him to remain in Chișinău and lead the Old Believer community there.

Though the bishop found refuge in Romania, he never obtained a Romanian passport. This would later have dire consequences for his fate.

In 1940, Romania ceded Bukovina and Moldova to the Soviet Union. Metropolitan Siluyan (Kravtsov) hastily fled the village of Belaya Krinitsa, and Bishop Innokenty left Chișinău, fearing that he would fall into the hands of his Bolshevik enemies.

Under the new circumstances, Siluyan relocated to the city of Brăila, which remains the residence of the White Krinitsa metropolitans to this day. Innokenty, meanwhile, was appointed bishop of the city of Tulcea.

In January 1941, Metropolitan Siluyan passed away. The Church Council elected Bishop Innokenty as his successor. In June of that same year, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, launching the Great Patriotic War.

Romania joined the war on Germany’s side, hoping to reclaim the lost territories of Bukovina and Moldova. At this time, Metropolitan Innokenty was in the border city of Iași, which the Soviet army mercilessly bombarded with artillery and airstrikes.

The hierarch found himself in a desperate situation. The Romanian authorities forbade him, a foreigner, from leaving the city. His friends and supporters fled from Iași, leaving Innokenty completely alone, without help or protection. Terror overcame him—he feared that the Red Army would soon enter the city and capture him.

Only in this weakened state did the Romanian authorities finally permit the Old Believers to transfer the hierarch to the estate of Pisk, three versts from Brăila, where a special cell had been prepared for him. There, Metropolitan Innokenty passed away.

For over forty days, he took no food and wasted away. His long-suffering soul departed to the Lord on February 16, 1942.

Ioann Kudrin #

In a family of Old Believers of the Chasovennye Concord, living in the village of Nozhovka in Perm province, Ivan Gavrilovich Kudrin, the future renowned priest, was born on December 10, 1879. His father, Gavriil Nikolaevich Kudrin, worked at the local factory, which produced cast iron and steel.

In 1886, the residents of Nozhovka accepted the priesthood of the Belokrinitsa hierarchy. A priest arrived in the village and, for the first time, performed a church service in the Old Believer chapel. He was vested in brocade vestments and censed not with a hand censer, as was customary among the common folk, but with a priest’s censer on chains.

This was unusual, and little Vanya Kudrin whispered to his peers:

— What is this? A priest in vestments, a censer on chains? The priest says “Again and again,” and they sing “Grant, O Lord.” No, this is not our way. Can this be right?

As it happened, Vanya began helping the priest—fanning and handing him the censer. And when he grew up, he himself became a priest and served God and the people faithfully for many years, enduring many hardships and trials.

The factory in Nozhovka went bankrupt, and the Kudrin family had to sustain themselves through farming and various trades.

A bright and sharp-witted young man, Ivan read avidly but indiscriminately. He lacked proper knowledge of history and theology, which troubled him. But the village nachetchik Zotik Ignatievich Khanzhin took charge of Kudrin’s education. He said:

— Listen, young man, do not despair, do not hang your head. You are young and, as I see, inquisitive. That means you must study and read. It is never too late to learn. If you have the will, you will find the time.

Under Khanzhin’s guidance, the young man eagerly began reading historical and theological books. He carried them with him to the fields, and during breaks, he read several pages and took notes. Soon, Kudrin was able to take part in debates with the priestless Old Believers and the Nikonians.

In 1898, Ivan married Anna Zotikovna, the daughter of Khanzhin. He combined his daily labors with reading books, studying church singing, traveling across the Urals, and engaging in discussions with those of other faiths.

The young man attracted the attention of Bishop Anthony (Paromov) of Perm and Tobolsk. In the summer of 1906, Anthony ordained Ivan to the diaconate. And on November 12 of the same year, he was ordained a priest. Father Ioann was tasked with establishing a parish in the settlement of Sarana.

The priest remained there for two years, but a community was never formed—local New Ritualists and priestless Old Believers opposed it. Thus, Kudrin was transferred to the village of Rukhtino, where priestly Old Believers lived and where a stone church was under construction.

In 1909, the completed church was consecrated in honor of the Nativity of Christ. Ioann served there for ten years. It was here that the October Revolution and the ensuing Civil War caught up with him.

In 1919, the priest and his family left Rukhtino, fleeing the advancing Red Army. Since many Old Believers were fighting against the communists and needed spiritual guidance, the generals of the White Army offered Kudrin the position of chief Old Believer priest of the army and navy.

Ioann agreed and served in this role for several years, retreating with the White forces from the Urals to the Far East, enduring the hardships and misfortunes of war. Many times, he risked his life, tending to the wounded and dying under cannon and machine-gun fire.

But the Whites lost the Civil War. Thousands of Russians, fearing Bolshevik brutality, fled to Manchuria, to the city of Harbin.

In 1923, Ioann also moved there. He became the rector of a small Old Believer parish in the city. By that time, Bishop Joseph (Antipin), who had previously overseen communities in the Far East, was already living in Harbin.

The faithful gathered for prayer in the bishop’s home, which was inconvenient. At a general meeting of the parishioners, it was decided to build a church. The bishop and the priest took an active role in this sacred endeavor.

On Christmas Day in 1924, Bishop Joseph elevated Ioann Kudrin to the rank of protopope (protopriest). And on August 16 of that year, the foundation stone of the Old Believer church was solemnly laid.

The community faced financial difficulties. But the bishop was so inspired by the construction of the church that when money ran out, he donated all his savings to the project. At last, the church was completed and consecrated on June 22, 1925, in honor of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul.

In 1945, the state of Manchuria ceased to exist. And in 1949, it was annexed to China. Life became unbearable for Russians in Harbin. Many emigrated to Australia and America.

But the priest continued serving in the church until almost all of his parishioners had left. In October 1957, Ioann, along with his family, set out for Australia, where his son Alexander was already living.

Before his departure, the few remaining Old Believers entrusted Ioann with icons, sacred vessels, and books from the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul so that they would not fall into the hands of the Chinese.

In January 1958, the Kudrin family set sail for Australia from Hong Kong. On the journey, a tragedy occurred—on January 15, Anna Kudrina suddenly passed away.

That morning, she saw a shark in the sea and sighed:

— Death has come for me! I will die here, on this ship. They will cast me into the sea to be devoured by sharks. I will never see Australia, nor my children.

Her companions tried to reassure her, saying that they had already traveled halfway, that the ship would soon arrive in port, and that nothing terrible would happen. But she went to her cabin, lay down, and by noon, she had passed away.

The priest had to conduct her funeral service and, contrary to Christian custom, bury her not in the earth but in the depths of the sea. After this unusual burial, Ioann told his children and grandchildren:

— Pushkin has an imperishable monument, and now your grandmother has one too. God created the ocean, and now it will be her monument, one that no one can destroy.

The loss of his wife deeply grieved the elderly priest and took a toll on his health.

In Australia, Protopriest Ioann settled in the city of Sydney. Through his efforts, a church was established there in honor of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul. The first Divine Liturgy in it was celebrated on January 7, 1959, on the feast of the Nativity.

But in February of that year, the priest suffered a mild heart attack. Then came a second. Kudrin’s entire right side became paralyzed. He lost the ability to move and speak, though he remained fully conscious.

After a prolonged illness, Protopope Ioann passed away on June 29, 1960. He was buried far from his homeland, in the suburbs of Sydney.

A Universal Lesson #

The Gospel contains not only the account of the life and teachings of Jesus Christ—the true God and Son of God. It also records the names of those who betrayed the Lord, condemned Him to crucifixion, and carried out His execution—Judas the Apostle, the high priests Annas and Caiaphas, and the Roman governor Pontius Pilate.

Judas betrayed his Teacher for thirty pieces of silver. After Christ was sentenced to be crucified, the apostle repented, returned the money to the high priests and elders, and then hanged himself. In the Russian language, the name Judas has become synonymous with traitor.

For the instruction of future generations, Church history preserves not only the names of the righteous—ascetics, martyrs, and confessors—but also the names of Judases—heretics, apostates, and betrayers.

In the dark days when the Soviet government was destroying the Church, some believers thought that it was easier to abandon their faith in order to save their lives rather than endure suffering for Christ. These unfortunate people traded eternal heavenly bliss for temporary earthly well-being. Sadly, at times, even members of the clergy were found among these Judases…

One devoted servant of God was Priest Makary Varfolomeevich Zakharyichev.

He was born in 1864 in the village of Zhuravlikha to a family of Old Believer peasants. He received a home education—learning to read from the Psalter and to sing using kryuki (the Old Believer chant notation).

In 1890, at the request of his fellow villagers, Makary was ordained a priest. His faithful companion and helper was his wife, Feodosia Stepanovna. The couple had six children.

Two years later, Makary Varfolomeevich was transferred to the city of Samara. At that time, the local Christians worshiped in a house church. Through the priest’s efforts, a magnificent iconostasis was installed in it. For his zealous service, Makary was elevated to protopope in 1903.

But the city chapel could no longer accommodate all the parishioners. So in 1913, the Samara community began constructing a large stone church.

A plot of land and substantial funds for the construction were provided by Maria Kondratyevna Sanina—the widow of the wealthy Old Believer merchant Ivan Lvovich Sanin, a well-known and respected entrepreneur and philanthropist in Samara.

Three years later, the cathedral, dedicated to the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, was completed and consecrated. But after the revolution, in 1918, the church was placed under municipal control. Dark times began for the community.

In 1921, Makary suffered a personal tragedy—his wife, Feodosia Stepanovna, passed away.

Several years went by. At the persistent request of Samara’s Christians, the widowed priest was honored with episcopal consecration. Everyone believed that the respected pastor, a dignified widower, and a father of many children, would be a good bishop.

In 1924, Makary Varfolomeevich took monastic vows and was given the name Mikhail. Then, Archbishop Meletius consecrated him as bishop of Samara. But Bishop Mikhail governed his flock for less than a year.

The devil tempted and destroyed him. The bishop became acquainted with a certain Anisiya Druzhinina, a woman from the village of Rozhdestveno, located on the opposite bank of the Volga, directly across from Samara.

Abandoning his parishioners and his church, the bishop moved in with Anisiya. She constantly reproached Zakharyichev for not being able to provide her with a luxurious life, demanding that he find a “real” job.

In June 1925, the Church tribunal suspended Mikhail from his duties for inappropriate behavior. Realizing that he had traded Christ, his flock, and his rank for Anisiya, the bishop fell into despair. But instead of repenting, he sought to silence his conscience with vodka.

The communists offered Zakharyichev a deal: if he publicly renounced his episcopal rank, they would secure for him a well-paid position. And Mikhail agreed.

The renunciation took place on October 1, 1925, at the Samara City Theater, during a public debate on religion, in front of a large audience.

The emergence of a new Judas made a heavy impression on the Old Believers. Even the apostate himself was deeply troubled by his betrayal. Immediately after the incident at the theater, he was visited by Priest Khariton Glinkin from Syzran.

Zakharyichev was dressed in secular clothing. His long hair, traditionally worn by clergy, had been cut short.

Astonished, Khariton asked:

— Is it true what they say about you?

After a moment of silence, the former bishop sighed:

— What is done cannot be undone.

After further questioning, Zakharyichev anxiously insisted that he had not renounced God:

— There He is! I believe and will continue to believe. I will go to Him, just by another path.

A month later, the former bishop came to confess before the Samara priest Grigory Maslov and repented of everything. But his repentance was insincere. Zakharyichev did not part with Anisiya or with vodka.

He moved from place to place, living in different villages and cities. For a time, he managed a warehouse at a brewery.

In March 1930, the apostate returned to Rozhdestveno, to Anisiya’s home. And on the morning of July 28 of that same year, the former Bishop Mikhail hanged himself.

With sorrow, Bishop Irinarkh (Parfenov) wrote about this to Archbishop Meletius:

“He followed in Judas’ footsteps! That one betrayed Christ and hanged himself. And Mikhail also renounced Him. And instead of weeping and accepting repentance, he ended his temporary life by suicide. Where did his soul go? There is a limit to everything. One cannot mock the omnipotence of God. This is a universal lesson.”

On Smoking Tobacco #

(from the teachings of Bishop Innokenty)

Last time, I showed how dreadful and ruinous, how harmful and sinful, how soul-destroying and repulsive the passion for drunkenness is. But no matter how destructive and shameful this vice may be, there exists another passion that is even more loathsome and even more harmful.

I am speaking of the unnatural habit of many people to cloud their minds and deaden their consciences with the stupefying smoke of poisonous plants—namely, tobacco. What could be more disgraceful and sinful than this vile indulgence?

A drunkard, when poisoning himself with alcohol, at least does so in a natural way—he drinks as nature has taught man to drink water. But the smoker poisons himself with smoke, taking it into his mouth and into his body.

Did God ordain that man should sustain himself with smoke? Is it natural to take the foul-smelling fumes of a poisonous plant into one’s mouth, to swallow it, or to inhale it, poisoning oneself? This is contrary to nature, contrary to the laws of creation, and therefore contrary to God, who established these laws.

Smoking tobacco, being an unnatural passion, places a person below the senseless beasts. If, according to the testimony of Saint John Chrysostom, a drunkard is worse than a donkey or a dog because of his lack of self-restraint, then how much worse is the tobacco smoker?

After all, a drunkard does not poison himself constantly, not every hour of the day. There are times when he sobers up, sometimes for long periods. But a tobacco addict poisons himself every hour—sometimes even several times within an hour. And at night, he has no rest: some will wake up ten times to smoke before morning.

To the smoker, nothing is sacred—neither fasting, nor feast days, nor prayer. Tobacco stands above God for him. As soon as he rises in the morning, instead of praying to God, he takes up his tobacco. And he does this regardless of whether it is a fast or a feast. If, by some effort, he restrains himself from smoking before the Liturgy, then during the entire service, his thoughts are consumed only with tobacco…

For the smoker, tobacco is like an idol to an idolater. In fact, tobacco is even worse than an idol.

An idol did not physically poison those who served it—it only separated them from the true God and cast their souls into destruction. But tobacco not only separates a man from God and hurls him into the abyss of perdition, but it also stupefies his mind, deadens his conscience, and degrades him below even the lowest of animals.

Bishop Raphael #

In the mid-19th century, certain writings began to spread among the Old Believers, promoting an unusual new teaching. These texts claimed that wine and potatoes were supposedly created by the devil and that Christians should not consume them. They also predicted the date of the end of the world and the Second Coming of Christ.

But most significantly, they declared that the Nikonians believed in and worshiped a different god—not the true God, Jesus Christ, but the Antichrist Jesus, who supposedly sat on the thrones of the Synodal Church’s temples.

Regarding this claim, it is important to note that in ancient Slavic books, the name of the Savior was traditionally written as Isus (Ісусъ). Under Patriarch Nikon, this spelling was altered to follow the Greek form—Iisus (Іисусъ). Disputes over how to write and pronounce the name of Christ became one of the causes of the Church schism.

However, never had it occurred to any Old Believer to declare that the name Iisus was the name of the Antichrist.

These absurd speculations caused considerable scandal among the faithful. Therefore, in 1862, on behalf of Archbishop Anthony, the Circular Epistle was issued to oppose this new teaching. It was prepared by the nachetchik Kabanov.

The Epistle stated:

“The most holy, most sweet, most beloved, and most desirable name of Christ our Savior we write and pronounce in reading and singing as ‘Isus,’ just as it was first translated into our Slavic language by the ancient holy translators. And so it was written and pronounced until Nikon, the former patriarch. We do not dare to revile the form ‘Iisus,’ written and pronounced by today’s Greeks and Russians, nor do we call it the name of another Jesus or the name of Christ’s adversary. For today, in Russia, the ruling Church, as well as the Greek Church, confesses the same Christ the Savior under this name. The only difference lies in the addition of a single vowel, ‘i,’ to the name ‘Isus,’ which results in ‘Iisus’ in print and pronunciation.”

However, intended to denounce heresy and unite the flock, the Epistle itself became a cause of discord.

Some Christians saw it as a betrayal of Orthodoxy and an attempt to appease the Synodal Church. Heated theological disputes erupted. Seeing the turmoil caused by the Epistle, the Council of Russian Bishops ordered its destruction.

But this did not help. The Old Believers split into supporters of the Circular Epistle—Okruzhniki—and its opponents—Neokruzhniki, or Anti-Okruzhniki.

The Belokrinitsa Metropolitan Cyril could not decide which side to take in the dispute and repeatedly changed his stance. Supporting the Neokruzhniki, he consecrated Bishop Anthony (Klimov) for them in 1864. This bishop became the founder of the schismatic Neokruzhniki branch of the Belokrinitsa hierarchy.

Among the Neokruzhniki, there were constant quarrels and conflicts. Their movement splintered into several warring factions.

Gradually, as they realized their error, the schismatics reconciled with the Ancient Orthodox Church and returned to it. The few remaining Neokruzhniki communities survived until the mid-20th century.

Bishop Peter (Glazov), the last schismatic bishop, died after the end of the Great Patriotic War. His flock, left without clergy, submitted to the authority of the Moscow Archbishop.

Among the Neokruzhniki bishops, Bishop Raphael is particularly notable. Not only did he overcome the schism and reunite with the Church, but he also sealed this holy unity with his martyrdom.

The future bishop, Roman Alexandrovich Voropayev, was born in 1872 in Little Russia, in the village of Novo-Nikolaevskoye, to a family of Neokruzhniki Old Believers. In his youth, Roman caught the attention of the local priest.

The priest said to Roman’s father:

— Alexander, we will prepare your son for the priesthood.

— No. I am already old, and our household is large. This son is my eldest; he must take care of our land, — Voropayev replied.

— Alexander, the hand of the Lord has pointed to your son. If you do not give your consent, I will excommunicate you from the Church! — the priest insisted.

Thus, Alexander Voropayev agreed. His son was first ordained a deacon and later a priest.

In 1920, Roman Voropayev was widowed, left with six children, the youngest of whom was barely three years old. In the autumn of 1921, the Neokruzhniki bishop Pavel (Turkin) tonsured the widowed priest into monasticism, giving him the name Raphael, and consecrated him as a bishop.

However, by May 1922, Bishop Raphael had reconciled with the Church and attended the council held at Rogozhskoye Cemetery in Moscow. From then on, he was a permanent participant in all Church Councils.

He was entrusted with overseeing parishes in various regions of Ukraine—Kharkiv, Kyiv, Odesa, and Cherkasy. Everywhere he served, Raphael proved to be a wise and kind shepherd.

These were terrifying times—marked by famine and unrest. The bishop often had to console his parishioners:

— If you are suffering, look at those who are suffering even more. Then it will seem easier to bear.

When he heard one Christian judging another, he would admonish:

— You see how a person sins. But you do not see how he repents.

In 1934–1935, the hierarch corresponded with many bishops and priests regarding the election of the Moscow Archbishop. Raphael supported Bishop Gury (Spirin) of Nizhny Novgorod. However, Bishop Vikenty (Nikitin) was chosen instead.

While residing in Cherkasy, on October 8, 1937, Bishop Raphael received a summons to appear at the police station. Knowing of no crime he had committed, he went without hesitation. He was immediately arrested and taken in for interrogation. The bishop was accused of speaking ill of the Soviet government.

Two informers testified against him. One claimed:

— During a church service, the priest said that the parishioners must defend their church. The communists will confiscate all churches and church property.

The second informer alleged that he had overheard the bishop at a market saying that the Bolsheviks were eliminating the best people and predicting a German invasion and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The next day, on October 9, Bishop Raphael was officially charged with inciting rebellion against the Communist Party and the Soviet government. A few days later, he was sentenced to death. And on October 24, 1937, Raphael was executed by firing squad.

The body of the holy martyr, along with those of other executed prisoners, was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Cherkasy. Today, the mass grave of the executed is lost. A city park now stands on the site of the former cemetery.

Bishop Vikenty #

No foreign invaders, no outsiders, no pagans or infidels could have devised torments as terrible as those inflicted upon Russia by the communists. Our country was turned into one vast prison. The tsarist penal system was replaced by labor camps. These were called correctional labor camps because, in the minds of the Bolsheviks, prisoners were meant to be reformed through labor.

A mere image of the slain Tsar Nicholas II, a joke about the Reds, or attending a church service could be grounds for denunciation. Denunciations, imprisonment, interrogations, torture, the labor camps, or execution became the everyday horrors of Soviet life. Millions of people passed through this hellish torment.

Among them was Bishop Vikenty, a martyr and confessor of the Christian faith. He endured and perished in the dungeons, like thousands of other innocent souls—slandered, tortured, and forgotten.

Vasily Semyonovich Nikitin—the future saint—was born on May 28, 1892, in the Kostroma village of Zamolodino, to a family of Old Believer Cossacks. His father, Semyon Nikitin, had faithfully served the Tsar and the Fatherland in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

From that war, he brought back a beautiful Turkish woman, whom he baptized and married. At that time, such marriages were not uncommon.

Settling in Zamolodino, Nikitin became a merchant. His business prospered, and soon he moved with his family to Kostroma, where they owned a house. However, his wife passed away early, leaving Nikitin to raise their children alone.

His wealth allowed him to provide them with a good education. In 1906, the merchant sent his son Vasily to study in Moscow at the Old Believer City School. Upon completing his education in 1910, Vasily returned to Kostroma. He chose the path of teaching and began giving lessons in Russian language.

Two years later, Vasily moved to the Perm village of Ocher. There, many Old Believers worked at the local factory, and through their efforts, a church was built in 1912, alongside which a school was established. Nikitin taught at that school for a year.

In 1913, Vasily left for Moscow and enrolled in the Old Believer Theological and Teaching Institute. However, he did not complete his studies—the First World War began. In 1916, Nikitin was drafted into the army.

In October 1917, the revolution took place. Afterward, the persecution of Old Believers resumed, harsher and more relentless than ever.

For Vasily, the war ended in 1918. He returned to Kostroma and married Maria Ivanovna Mokhova, the choir director of the local church. Although Maria was three years older than her husband, they lived in harmony. In June 1919, the young couple welcomed their daughter, Kaleria.

However, in August, Vasily was drafted once more—this time into the Red Army. For two years, Nikitin served as a cultural officer, teaching illiterate Red Army soldiers to read and write. He rejoiced at the moment he was finally discharged.

The very day after returning home, Vasily Nikitin was ordained a priest for the parish in the village of Kunikovo.

Before long, Vasily met Bishop Geronty (Lakomkin), a native of Kostroma. The bishop frequently visited his homeland, assisting his fellow countrymen in building churches and establishing schools. He was greatly impressed by the educated and active young priest.

Together, they founded several church schools. However, there was a shortage of teachers, so in 1924, it was decided to begin training parish teachers in secret from the Bolsheviks. The authorities soon caught wind of this. Vasily was arrested and held in custody for about a month before being released on the condition that he would not leave the area.

Staying in Kunikovo was too dangerous. Therefore, on the advice of Geronty, in February 1925, the priest was transferred to Moscow, to serve at the churches of Rogozhskoye Cemetery.

But life had prepared for the young priest a new trial, the most painful and sorrowful yet. In January 1926, Maria Ivanovna suddenly passed away. Vasily was left with his daughter Kaleria and his son Lev. His grief was immeasurable—he lost weight, his face grew gaunt and dark. He often visited his wife’s grave and wept.

In September 1928, the last Church Council before a long hiatus was convened—after this, the communists forbade councils from taking place. At this council, Vasily was offered episcopal consecration.

The priest refused, but he was persuaded with great difficulty. It was decided that he would become the archpastor for Christians in the Caucasus. Humbly accepting, Vasily tearfully pleaded:

— Just do not abandon my children!

During the very session of the Council, the priest took monastic vows with the name Vikenty. A week later, he was consecrated a bishop. Along with his children, he departed for Yessentuki, where he settled in a small guardhouse near the church.

But in his new place of service, further troubles awaited the bishop. On April 13, 1932, he was arrested and imprisoned. The charges against Vikenty were absurd—he was accused of uniting Christians in the Caucasus to fight against the Bolsheviks, of preparing an armed uprising, of spying on Soviet military secrets for Romania, and of possessing a portrait of Tsar Nicholas II.

The bishop was sentenced to ten years in a labor camp. However, he served only one. He had suffered from leg ailments since the war, and in captivity, his condition worsened. Thus, in September 1933, he was granted early release on account of his health.

In 1934, the head of the Russian Church, Bishop Meletius, passed away. A council needed to be convened to elect a new archbishop. However, under the prevailing circumstances, this was impossible.

Correspondence among the bishops ensued. As a result, Bishop Vikenty was chosen as locum tenens—the temporary head of the Church.

The saint settled in Moscow, serving not only in the Intercession Cathedral at Rogozhskoye Cemetery but also in all the remaining Old Believer churches. After the Divine Liturgy, he would deliver sermons—an act of great courage in those times.

But Bishop Vikenty’s tenure as locum tenens was short-lived. On January 30, 1938, the newspaper Izvestia published a slanderous article titled The Archbishop of All Russia, aimed at discrediting the hierarch in the eyes of the faithful. He was accused of every imaginable and unimaginable crime—allegedly, he had been a White Army officer, a Romanian spy, a notorious drunkard, and a fraudster. Thus began the persecution of the bishop.

On the evening of March 5, 1938, Bishop Vikenty was arrested and taken to prison. There, after yet another round of interrogations, he died on the night of April 13 from severe beatings. His executioners burned his body, and his ashes were buried in a mass grave at the Donskoye Cemetery.

Bishop Geronty #

The life of Bishop Geronty reflects the history of the Church in the 19th and 20th centuries like a mirror. Overcoming many hardships, he preserved both his sincere faith and the dignity of his episcopal rank.

Grigory Lakomkin—the future saint—was born on August 1, 1872, in the Kostroma village of Zolotilovo to the family of Priest Ioann Lakomkin. His parish was poor, so the priest’s family had to sustain themselves through peasant labor. In addition, Ioann was constantly persecuted by the authorities. The heavy and troubled life took a toll on him—he fell ill with tuberculosis and passed away.

Under the guidance of his older brother, Grigory studied church singing and liturgical rules. In 1896, he married a pious young woman, Anna Dmitrievna Pechneva.

According to the custom of the bride’s village, the newlyweds were expected to dance at the wedding. But Grigory refused to participate and forbade Anna as well:

— If you allow dancing, then you will no longer be my bride but Satan’s. In that case, I must leave this gathering and no longer consider you my betrothed.

The dancing did not take place, surprising the guests, who whispered:

— The Old Believers are so stubborn—they refuse to follow local customs!

In 1899, Lakomkin was drafted into the army. After serving for five years, as was customary, he returned home. In 1906, Bishop Innokenty ordained him a priest for the village of Strelnikovo, near Kostroma, where the previous rector had unexpectedly died.

The bishop warned the young priest:

— The people in this village are given to heavy drinking; they are quick-tempered.

When Lakomkin arrived, he found the church in a wretched state—there was no iconostasis, dirt and grime were everywhere, and the ceiling seemed ready to collapse. The affairs of the parish were in disarray.

The widow of the previous priest wept as she told him:

— The people here are terrible, like wild beasts—drunkards. May God grant that you serve even one month. You will starve!

But through Grigory’s diligence, the church was repaired and rebuilt, a parish school was established, and a temperance brotherhood was formed. The church choir of Strelnikovo became one of the finest in Russia, and the parish itself became exemplary.

In 1908, the priest was widowed—Anna Dmitrievna passed away suddenly. At the Church Council of 1911, the widowed priest was elected bishop for Saint Petersburg and Tver. Grigory took monastic vows with the name Geronty and was then consecrated a bishop.

Bishop Geronty was one of the most active hierarchs. He participated in church councils, engaged in educational work, and worked tirelessly to build new churches and open parish schools.

Then came the year 1917. Archbishop Meletius left for the Don. In Moscow, only Bishop Alexander (Bogatenkov) of Ryazan remained. He asked Geronty to travel across the country and send reports on the state of church affairs.

In one of his letters, Geronty compared the Church to a vineyard and foretold impending calamities:

“Most seem to be asleep and have entirely abandoned this field and vineyard, being carried away by other pursuits. Woe, terrible woe awaits us—the sleepers and the negligent! The Master will surely demand a full account of everything. How shall we justify ourselves? And what will become of the vineyard?”

His prophecy soon came to pass—the Church’s vineyard was trampled underfoot by the communists.

In 1933, the cathedral at Gromovskoye Cemetery in Leningrad was closed and blown up. A year earlier, on April 13, 1932, Bishop Geronty had been arrested and imprisoned.

The bishop was sentenced to ten years, allegedly for opposing the Soviet government. Upon hearing his sentence, he asked:

— Could you not give me more?

When told that a longer term was not possible, he responded:

— Thank God that I am already 60 years old! I must live to 70 and serve my sentence honestly. After that, either I will die or I will go home.

The saint’s courage astonished the judges and interrogators. But life in captivity was harsh for him.

As a monk, he did not eat meat and had to subsist on bread alone. This led to the development of scurvy in prison—his teeth became so loose that they could be pulled out by hand. His legs swelled so badly that he could no longer fit them into his boots.

From prison, Geronty was sent to a labor camp. His beard was shamefully shaved off. He was transferred from one camp to another several times. Everywhere he saw the same horrors: thousands of innocent prisoners, cruel treatment, backbreaking labor, starvation, and disease.

The bishop discovered that a miraculous cure for many ailments was a special pine-needle kvass that he devised.

In one of the camps, he was assigned as an assistant to the prison doctor. There, he decided to make kvass from pine needles. He even invented a machine to pluck the needles efficiently. The drink turned out to be excellent! The camp authorities valued his work and took a liking to the tart beverage themselves.

Thus, when Bishop Geronty’s ten-year sentence ended in 1942, he was kept in the camp to continue overseeing the preparation of kvass and the collection of mushrooms, berries, and pine needles. He was even given a salary of 200 rubles per month. However, since the Great Patriotic War was underway, he donated his earnings to support the defense of the Motherland.

It was not until November 5, 1942, that Geronty was able to return to Strelnikovo. In 1943, Archbishop Irinarkh (Parfenov) invited him to Moscow and appointed him as his assistant.

In 1944, Old Believers received permission to publish a church calendar for the following year. Geronty took on the task of preparing the publication. He hoped that the authorities would eventually allow the printing of a Christian journal and the reopening of a seminary to train priests. Unfortunately, these hopes were never realized.

In 1948, the communists returned the Resurrection Church-bell tower at Rogozhskoye Cemetery to the faithful. From then on, daily services were conducted there. In 1949, the former funeral chapel was transferred to the archbishop’s administration. It was renovated, and Archbishop Irinarkh, along with his assistants, moved into it.

Geronty remained a constant and tireless participant in all church affairs. In 1949, he wrote a memoir—an impartial testimony of those times.

Reflecting on his life, he wrote:

“Glory be to God for everything! But it is a great sorrow that so little, far too little, was accomplished. More should have been done, but frailty, weakness, and the vanity of life have stolen much time into idleness—for which I must answer before God.”

In October 1950, the bishop fell ill with pneumonia. He had suffered frequent and prolonged illnesses before—his years in the labor camps had taken their toll. But this final illness proved to be his last.

On May 25, 1951, Bishop Geronty departed from his earthly labors and cares, entering into eternal rest in the Kingdom of Heaven.