The Church and War #

In thirty years of Soviet terror, the communists accomplished what the tsarist authorities had failed to do in 250 years of Old Believer persecution. The Church was nearly destroyed.

The communists imposed enormous taxes on priests. Some, unable to pay, renounced their priesthood. Others sought help from their parishioners. When this assistance proved insufficient, priests were forced to sell their possessions—everything from houses, horses, and cows to samovars, glasses, and teaspoons.

The Bolsheviks banned the religious upbringing of children. In schools, teachers mockingly told students that God did not exist. They instilled in them the belief that faith in God was shameful, something primitive and ignorant, claiming that only illiterate old women believed in Him.

On church holidays, especially Easter, teachers stood outside churches to ensure that children and young people did not enter. Even harmless traditions, such as Christmas trees and gifts, were forbidden.

Students were inspected to see if they wore crosses. If a child was found wearing one, it was torn from their neck. The unfortunate student was brought before the class and publicly shamed.

Churches stood empty. The number of priests dwindled to levels unseen since the persecutions under Nicholas I. Almost all bishops had been executed. The elderly and ailing Bishop Savva (Ananyev) of Kaluga and Smolensk lived out his final days, while Bishops Geronty (Lakomkin) and Irinarkh (Parfenov) languished in labor camps.

In 1936, Irinarkh was released from prison and moved in with relatives in Kostroma. He was so terrified that he no longer engaged in church affairs.

In the spring of 1941, he was summoned by the head of the city militia. Expecting more trouble, Irinarkh was astonished when he was told that Moscow’s Old Believers were searching for him and urgently requested his presence at Rogozhskoye Cemetery.

In the capital, he was met by Protopope Vasily Korolev (1891–1962), the rector of the Intercession Cathedral. Together, they traveled to Kaluga, where Bishop Savva consecrated Irinarkh as Archbishop of Moscow and All Russia.

That summer, on June 22, 1941, the Great Patriotic War began. Germany attacked the Soviet Union.

This was not merely a war for territory or global influence. The Germans considered themselves a superior race and viewed the Slavs as worthless savages fit only for servitude. They sought to exterminate the Russian people and erase all memory of them. They intended to settle on Russian lands and turn any surviving Russians into their slaves.

Archbishop Irinarkh addressed his flock with an appeal:

“Let every man who can bear a sword go forth to the battlefield. Let every man who can work in the fields, factories, and workshops labor honestly for the good of our homeland.”

As bitter as Soviet rule was for the Old Believers, falling under German occupation would have been even worse. From the very beginning of the war, thousands of Christians enlisted in the Red Army. They understood that Germany was not merely fighting the Soviet Union—it was waging war against Russia and the Russian people.

To this day, in the remnants of battlefields, in mass graves, collapsed dugouts, and overgrown trenches, search teams frequently uncover Old Believer crosses and cast icons—a testament to the Old Believers who never returned from war.

On the home front, believers sought to support the army. At the Intercession Cathedral, donations were collected during services. Across the country, Old Believers contributed 1,200,000 rubles to the defense of the homeland.

By October 1941, the Germans were approaching Moscow. Battles raged at the city’s outskirts. The Soviet government decided to evacuate the leaders of major religious communities to the rear, to the city of Ulyanovsk. Among those chosen for evacuation was Archbishop Irinarkh.

They were to travel by train, with a special carriage assigned to representatives of different faiths. The war had temporarily set aside religious divisions. The Old Believer archbishop shared his journey with the Nikonian Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky), the future Moscow Patriarch.

Yet, despite this, Old Believers continued to face accusations of opposing the Soviet government.

For instance, in 1942, in the Ural village of Pristan, the priest Nikifor Zaplatin was accused of allegedly urging men preparing for war to defect to the Germans and sabotage the Red Army during confession. The authorities demanded that he name those who had confessed to him, but he refused to betray anyone.

The slandered priest disappeared into the labor camps, never to be seen again…

In March 1943, after fierce and bloody battles, the Red Army drove the Germans out of Rzhev. The city had been almost completely erased from the face of the earth. Only a few buildings remained standing, among them the Old Believer Intercession Church. The German occupiers had herded 300 surviving townspeople into the church and rigged it with explosives.

However, in their hasty retreat, the Germans failed to detonate the charges. The townspeople remained locked in the church for three days without food or water. Among them were believers and non-believers, Old Believers and Nikonians, Russians and non-Russians. Those who knew how to pray did so, while those who did not asked others to pray for them.

The people of Rzhev were freed when Soviet soldiers arrived. When the troops disarmed the explosives and opened the doors of the church, there were no longer any atheists among the survivors. A shared suffering had opened their spiritual eyes.

In 1944, when the Red Army occupied Moldova, Archbishop Irinarkh gave his blessing for the printing and distribution of pamphlets urging the local Old Believers to support the Soviet forces.

In May 1945, the war came to an end. The archbishop sent a letter of congratulations to the Supreme Commander:

“The glory of your remarkable victory shall never fade. Future generations will recall these days of Russian triumph with pride.”

Archbishop Irinarkh passed away on March 7, 1952. He was succeeded as Moscow Archbishop by Bishop Flavian (Slesarev).

In November of the same year, Flavian received a letter from Romania, written by Metropolitan Tikhon (Kachalkin) of Belokrinitsa.

Tikhon wrote that in 1944, the Germans had bombed the printing house that produced liturgical books. The Old Believers in Romania were now in great need of books. Was it possible to send them from Moscow?

He also expressed his desire to retire but wished first to transfer the residence of the Old Believer Metropolitans from Brăila to Moscow and elevate Archbishop Flavian to the rank of Metropolitan.

Unfortunately, this plan was not realized at the time. It was only in 1988 that the Moscow Archbishop was officially elevated to the rank of Metropolitan.

Andrei Popov #

The city of Rzhev had long been known for its large Old Believer community. At the beginning of the 20th century, many of its inhabitants adhered to the ancient faith.

The city had two Old Believer churches. Of one, the Trinity Church, only the bell tower has survived to this day. However, the second church, the Intercession Church, remains intact.

The wooden Church of the Holy Trinity, with its stone bell tower and chapel dedicated to Archangel Michael, was laid in 1906 and consecrated three years later.

The stone Church of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos was founded in 1908, built by the renowned architect Martyanov. By 1910, the new church was consecrated. Ten years later, Father Andrei Popov was assigned to serve there.

Andrei Pavlovich Popov was born in 1883 in the village of Zadvorka on the Vetluga River, a tributary of the Volga. His parents, Pavel and Pelageya, were simple Old Believer peasants.

In his youth, Andrei aspired to become a teacher. He left home to enroll in a teacher’s seminary, completed his studies, and returned to his parents.

In 1910, Andrei married Alexandra, the younger sister of Father Nikandr Ivanovich Kolin, who served in the neighboring village of Budilikha. A year later, Andrei Popov was ordained to the priesthood by Bishop Innokenty of Nizhny Novgorod.

The young priest was assigned to the village of Kovernino on the Uzola River, another tributary of the Volga. In 1916, he was sent as a regimental priest to serve in the active army on the battlefields of World War I. For his bravery, he was awarded the Cross of St. George.

Returning from the war, the priest was forced to go into hiding from the Bolsheviks in Budilikha, at his wife’s relatives’ home. He could no longer live and serve in Kovernino. To save Father Andrei from persecution, the church authorities secretly reassigned him to the Intercession Church in Rzhev.

Popov and his family arrived in Rzhev in May 1920. Having spent several years in enforced idleness, he zealously resumed church affairs. A gifted preacher, he tirelessly delivered God’s word and dedicated himself to the spiritual education of his parishioners.

Father Andrei devoted particular effort and time to the church choir, as he was well-versed in and loved Znamenny chant. Later, in recognition of his tireless service, Bishop Geronty elevated Andrei Popov to the rank of protopope. On this occasion, the parishioners presented their pastor with a gold pectoral cross.

The Soviet authorities, however, had their own judgment of Andrei Popov’s efforts. Before Easter in 1929, he was arrested and sent to prison. He was then sentenced to five years in a labor camp, followed by two years of exile in Astrakhan.

During this time, in the summer of 1932, Father Nikandr Kolin was murdered. He had been rowing in a boat on the Vetluga River, traveling to a neighboring village to perform religious rites. The assassin lay in ambush and shot him with a rifle.

The priest’s body was later discovered in the boat, far downstream. No one was ever held accountable for the crime.

In September 1934, the Bolsheviks closed the Trinity Church in Rzhev. The House of God was repurposed as a club. Now, instead of the Divine Liturgy being celebrated on Sundays, dances were held there. During the war, the church burned down, leaving only its bell tower.

However, much of the Trinity Church’s icons, books, and liturgical items were saved from destruction by Deacon Feodot Tikhomirov, who had served there. He managed to preserve these sacred objects and transfer them to the Intercession Church.

Father Popov returned to Rzhev in 1936. Yet, the authorities did not permit him to serve at the Intercession Church. Instead, he moved to the town of Taldom, where he served for several years at the small Church of Archangel Michael.

Shortly before the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War, the communists closed the church in Taldom. The priest returned to Rzhev. This time, he was allowed to serve at the Intercession Church.

Then, the war began.

In August 1941, the Germans entered Rzhev. Father Andrei did not flee the city. In those dark days, he remained with his flock. Services continued to be held in the church.

However, the number of parishioners steadily dwindled. Some were killed in bombings and shelling. Others were executed by the occupiers. Some were taken to Germany for forced labor.

It was impossible to walk the streets of Rzhev unnoticed. One day, the Germans spotted a dark-haired man whom they mistook for a Jew and wanted to execute.

However, the man tried to explain that he was Russian, a parishioner of the Old Believer church, and that Father Popov knew him. The Germans took the detainee to the priest. Andrei confirmed that the man was his parishioner, Vinogradov, thus saving his life.

More than once, the protopope saved people. He sheltered those who came to the city and feared falling into the hands of the occupiers. In his house, there was a Russian stove, and beneath it—a space for firewood.

Popov hid those seeking refuge there.

But traitors were watching the priest. Due to their denunciations, the Germans repeatedly came to his home to search it. However, they never thought to check under the stove.

On the evening of September 12, 1942, a fire broke out in the city.

Protopope Andrei, Deacon Feodot, and several parishioners climbed the church bell tower to see where the fire was burning. After observing the blaze, they began descending and entering the church.

At that moment, a German soldier ran up and shot Popov at point-blank range.

The priest fell, crying out:

— Why such punishment?

More shots followed.

The parishioners rushed over, lifted their bloodied pastor, carried him into the church, and laid him on the floor near the right choir stall.

Popov had been shot in the abdomen with an explosive bullet. It passed through him and tore open his back. For two hours, the priest lay dying in excruciating agony, having lost a great deal of blood. Yet, he endured his suffering with patience. He even had the strength to bid farewell to his parishioners.

The protopope passed away. He was hastily buried near the church, on the southern side, without the customary hymns.

Christians appealed to the German officers, asking them to punish the murderer. But the officers refused to investigate the death of the “Russian priest” and even threatened the believers with more executions.

The Germans entered the Intercession Church. They behaved insolently, disrupting prayers and committing outrages. They put on wedding crowns and priestly vestments, danced in them, and sang. They sat on the holy altar and drank alcohol. The soldiers stabbed and shot through the old liturgical books.

Only after Rzhev was liberated from the Germans and the new priest, Ioann Prozorov, arrived in the city were the appropriate prayers finally offered over Andrei Popov’s grave. The protopope’s grave has been preserved to this day.

On the Old Faith #

(from the spiritual testament of Bishop Geronty)

Remember, dear ones, that we believe in the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, the Church of Christ. And we remain steadfast in the true old faith, in which the saints and righteous ones of God lived. That is why, unlike others, we are called Old Believers.

We uphold the sacred traditions and ancient rites in which all the holy servants of God in our land have abided. That is why we are also called Old Ritualists.

Our ancestors endured countless torments for this holy old faith, for the sacred traditions and ancient rites. Thousands of them were slain, shedding their holy blood for the true faith, and were found worthy to be numbered among the saints of God…

With tears, I implore and solemnly bequeath to you: firmly and unwaveringly keep our holy and true faith, for it is the true faith. You are blessed to abide in it…

With tears, I implore, plead, and give my fatherly testament: let peace and love be in every family. Let children honor their parents, knowing that whoever wishes to be happy and prosperous must honor their father and mother, as the fifth commandment of God teaches. And parents, do not provoke your children…

Husbands and wives, strictly and unbreakably keep marital fidelity. Let no one live without a church wedding… Strive to ensure that your children harbor no malice, falsehood, slander, foul language, drunkenness, theft, envy, or vengeance, nor any other such sins.

Let not the sun set on your anger. Always forgive one another. Especially at night, you must always reconcile.

Do not forget the feast days and Sundays, when you must certainly attend the communal church service—Vespers and the Divine Liturgy. In the House of God, stand with fear and reverence, without idle talk, as if you were in heaven. Do not leave the holy church before the end of the service.

Do not be stingy in your offerings to the holy church and the poor. At home, pray every day—morning, evening, and at midday, as well as before and after meals, as indicated in the holy books.

Pray without haste, with reverence. And even more so, strive to make the sign of the cross and bows with deep devotion, without rushing. Make the sign of the cross with two fingers, as established by the Church of Christ.

Semyon Kuznetsov #

In 1894, in the Nizhny Novgorod village of Chernukha, Semyon Illarionovich Kuznetsov was born—an Old Believer ustavshchik (liturgical reader and cantor) who lived an astonishingly complex and eventful life.

Originally, the inhabitants of Chernukha were adherents of the Nikonian church but still made the sign of the cross with two fingers. Illarion, Semyon’s father, was a child when the village heard about the priesthood of the Belokrinitskaya hierarchy and embraced it.

The local synodal clergy tried to eradicate the old faith in Chernukha, threatening Siberian exile. But the believers were not afraid.

Semyon Illarionovich was born into the Old Believer faith. In just one winter, he mastered church literacy and Znamenny chant.

In his youth, Kuznetsov had an extraordinary bass voice. Bishop Innokenty of Nizhny Novgorod, under whom Semyon served as a cell attendant for a time, recognized this.

Once, Semyon was traveling with the bishop on a steamboat along the Volga. The hierarch said to Kuznetsov: “Semyon, glorify the Lord, sing to Him. Do not be shy. God will bless you.”

The cantor began singing “Lord, I Have Cried Unto Thee.” Suddenly, a shout came from the ship’s captain: — “Who just sang ‘Lord, I Have Cried’? Immediately move to the other side and sing it again, or we will capsize!

People rushed to see the owner of the wondrous bass, and the steamboat tilted significantly.

With the bishop’s blessing, Kuznetsov went to Moscow, enrolled in the Old Believer Theological Institute, and completed his studies. But then, World War I began. In 1914, Semyon volunteered for the army.

For his bravery, Kuznetsov was awarded several St. George’s Crosses and was promoted to officer rank. In 1917, the Old Believer served in the guard of Emperor Nicholas II. When revolutionary unrest began in Petrograd, the guards, kneeling, pleaded with the Tsar:

“Command us, Sovereign! We shall put all of Petrograd on its knees!”

The Autocrat listened to his loyal warriors—there were nearly a thousand of them—but merely waved his hand. It seemed he did not believe them.

The revolution took place. Semyon returned to his homeland. On the way, he saw that in every village the people were drunken. He asked the men:

“What has happened?”

They replied:

“Soldier, do you not know? The revolution!”

It turned out that the revolutionaries had looted and destroyed the vodka distillery in Arzamas. Now, the whole region was celebrating the beginning of a new life.

After living in Chernukha for some time, Kuznetsov traveled to Nizhny Novgorod to see Bishop Innokenty. In the autumn of 1918, the Bolsheviks decided to seize and execute the archbishop. They surrounded his house, allowing only laypeople to leave. Clergymen were detained.

The Old Believers who were in the house resolved to save Innokenty. They dressed him in civilian clothes and successfully led him out of the building. Meanwhile, Semyon stayed behind in his place. He donned the archbishop’s mantle and sat in the bishop’s room.

The communists seized him, thinking they had captured Innokenty, and took him to prison. In the cell, an old man turned to Kuznetsov:

“You seem to be in a bishop’s robe, but you don’t quite look like a bishop. How did you end up here?”

Semyon told him that he had been taken instead of the bishop.

“Listen,” the old man whispered, “they’re going to shoot us all here. But you—pretend to be drunk and lie down. When they try to wake you, just say you remember nothing.”

Kuznetsov did exactly that. He removed the bishop’s mantle and lay down on the bench. In the morning, the Bolsheviks began leading the prisoners out to be executed. They tried to rouse Semyon, but he would not get up. The commander arrived and asked:

“What’s with this man? Is he drunk?”

“I don’t know,” the Old Believer replied. “I am soldier Semyon Kuznetsov, returning from war. Yesterday, I had a little too much in the tavern. I don’t remember anything else.”

They laughed at him and let him go. Many times afterward, death threatened Kuznetsov, but he miraculously escaped it.

For instance, in 1929, on Great Thursday, the communists, seeking to disrupt the celebration of Pascha, seized all the priests, deacons, and precentors in Arzamas and the surrounding area. They were herded into the city prison and then forced to march to Nizhny Novgorod under the aim of soldiers’ rifles.

Upon reaching the Serezha River, the believers were given a choice:

“Whoever wants to cross the bridge must remove his crosses. Whoever refuses—God help you, cross the river yourselves!”

The ice on the river had begun to thaw. In some places, water was already visible. The believers did not know what to do. Many fell to their knees and begged the soldiers for mercy. Kuznetsov could not bear it any longer—he made the sign of the cross, began singing “Volnoyu morskoyu” (“By the Sea’s Wave”), and stepped onto the ice.

The people took up the hymn, followed Semyon, and safely crossed to the other side.

The soldiers rushed onto the ice to pursue them, but the ice gave way, and they all plunged into the freezing water.

The believers did not wait to see whether the soldiers would manage to climb out—they scattered in all directions. The Old Believers from Chernukha continued on to Nizhny Novgorod. From there, Kuznetsov set off for Tomsk and then to Minusinsk.

Fearing Bolshevik persecution, Semyon fled from Siberia with his family to Tuva. Later, he returned to Minusinsk, where he was eventually caught by the Soviet authorities. In 1946, Kuznetsov was arrested for living under false documents.

Sentenced to 25 years, the Old Believer found himself in a labor camp. He refused to shave his beard, openly prayed and fasted, and did not work on feast days. The camp commander learned of this and, during Holy Week, summoned Kuznetsov, ordering him to sing Paschal hymns.

“When Pascha comes, invite me, and I shall sing,” the Old Believer boldly replied. “But this place is unfit for singing. There are no icons. To whom shall I sing? To please your ears?”

“How dare you speak like this!” the commander fumed. “What kind of man are you, Kuznetsov? So many years of Soviet power, and yet you still cling to your faith!”

“I am Simeon, not a chameleon. Winter and summer, I am the same color. That is why I am here.”

“Enough, go.”

When the holy feast arrived, the Old Believer was brought before the commander. In his office, there were icons and candles. The entire camp leadership had gathered, laughing:

“Well, Kuznetsov, you promised to sing for Pascha. Sing!”

Astonished, Semyon began the festive service. At the end, he turned to those assembled and proclaimed:

“Christ is risen!”

And in unison, he heard the reply:

“Truly He is risen!”

The camp commander sighed:

“Ah, Russia, you cannot be imprisoned here!”

And three months later, Kuznetsov was granted early release. He returned to Minusinsk. In that city, through the efforts of Semyon Illarionovich, his children, and his grandchildren, a church was built in honor of the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos.

Kuznetsov died in 1981. Two months before his repose, he was praying in church. Suddenly, the icon of Simeon the God-Receiver fell. The precentor picked it up, kissed it, and smiled:

“They have come for me.”

Soon after, the venerable elder fell ill. People came to bid him farewell. As he lay dying, he asked whom he should greet in the next life.

Ilya Blizhnikov #

In 1888, in the village of Krasny Yar near Elisavetgrad, a son, Ilya, was born to the peasant Old Believers Ignaty and Paraskovia Blizhnikov.

Like his parents, Ilya worked the land. He also learned masonry and could build any kind of stove. At the same time, he faithfully attended the Old Believer churches—there were two in the village. Serving at these churches were his elder brothers, Andrey and Illarion, both priests.

Upon reaching adulthood, Ilya married a maiden, Anisia Dievna, the only daughter of fellow Old Believers in the village. Three children were born to them: Maria, Ivan, and Feodor, who perished in the war.

In the early 1920s, Ilya was ordained first as a deacon and later as a priest by Bishop Raphael (Voropaev) for the village church where Andrey Blizhnikov served.

However, Father Ilya did not serve in Krasny Yar for long—only until the late 1920s. Persecution of the faith began. The Bolsheviks shut down the churches in the village. Andrey was imprisoned and perished in jail. Illarion disappeared without a trace—he was likely executed.

Ilya had his home and livestock confiscated. He was beaten severely several times as they demanded that he renounce God. Once, he was beaten so badly that he was bedridden for a long time and struggled to recover.

Finally, the communists threatened:

“We’ll hang you if you do not renounce the Church!”

Blizhnikov then wrote a letter to Archbishop Meletius, requesting to be transferred somewhere in Russia, to a remote parish. The letter reached Bishop Gerontius, who invited the priest to the Pskov village of Sysoyevo.

Ilya and his wife moved to their new home. Their children remained in Krasny Yar with relatives.

There was no clergy housing at the church in Sysoyevo, so the couple settled on the homestead of the Old Believer family of the Fyodorovs. From that day until the end of his long life, the priest served in Sysoyevo.

The Blizhnikovs lived on the Fyodorov homestead for nearly three years. The local authorities did not interfere with the priest. But in April 1932, grim news arrived from Leningrad—Bishop Gerontius had been captured and imprisoned.

Ilya feared that he would be next. Not wanting to endanger the Fyodorov family, who had many children, the Blizhnikovs left their hospitable home.

In the summer of 1932, the parishioners built a small hut for their pastor. Then, in 1937, the authorities closed the church in Sysoyevo. From then on, Christians were forced to pray in their homes.

Father Ilya had a portable church. Occasionally, he secretly celebrated the Liturgy in his hut or at the home of a parishioner.

In 1941, the Great Patriotic War began. The German army occupied the Pskov region. For reasons unknown, the occupiers deported Ilya and Anisia to Estonia. There, an incident occurred.

As the day of the Latin Pascha approached, the Germans, having learned that there was a priest among the Russians, tried to force him to conduct the festive service.

The occupiers gathered their soldiers and local residents and announced:

“Here is your priest. Now we will make him serve Pascha!”

But Ilya refused.

“I cannot serve as you demand. I am an Orthodox priest.”

The Germans were enraged and sent the priest and his wife to a concentration camp in Germany. There, the Blizhnikovs languished for nearly two years.

Then the Soviet forces arrived and liberated the prisoners. The couple set out for Russia on foot, taking with them two orphaned girls from the camp.

The Blizhnikovs returned to Sysoyevo. The church was still closed. Then, believers from the Pskov village of Korkhovo reached out to Ilya.

In this village, a wooden church dedicated to St. Nicholas the Wonderworker had been built in 1908. In 1937, the communists shut it down. The church warden, Pyotr Grechin, was arrested and sent to prison.

As Grechin was being taken away, he turned to his daughter:

“Here, Natasha, take the keys to our church. Keep them safe, and the Lord will help you.”

He handed his daughter a bundle of keys, kissed her forehead, and left with the soldiers, vanishing forever into the Soviet prisons and labor camps.

Thus, Natalia Petrovna Grechina (1912–1996) became the keeper of the Korkhovo church. She was only 25 years old. But no matter how much she tried to entrust the keys to one of the elder parishioners, all refused:

“Natalya, let the keys stay with you. If anything happens, you have no children, so they will not be left orphaned. Have mercy on us—keep the keys yourself!”

Natalya took pity on them and kept the keys.

Time and again, officials demanded:

“Give us the keys to the church—we are taking it from you!”

Natalya’s answer never changed:

“We will not give you the keys to the church, nor will we allow you to defile the holy place. Do as you will, you are the authorities.”

Thus, Grechina preserved the church. After the war, she managed to have it reopened and invited Blizhnikov to serve in Korkhovo.

In 1947, Archbishop Irinarch entrusted Ilya with serving in the Church of St. Nicholas. The new parishioners took to the priest and begged him to stay in their village. They even found a house for him.

Father Ilya decided to move to Korkhovo, but the people of Sysoyevo persuaded him to remain. Thus, he began to serve both parishes. Then, in secret from the authorities, he built a small prayer house in Sysoyevo, hidden away behind gardens in a lowland.

In the 1950s, Anisia Dievna passed away. Their eldest daughter, Maria, took care of her father. She was his housekeeper, nurse, and reader at the prayer house.

During this time, the priest also began ministering to the Christians in Leningrad, who had been without churches and priests since the 1930s.

Now an old and ailing man, suffering from leg ailments, he not only had to serve in Sysoyevo but also traveled monthly to Korkhovo and, whenever summoned, journeyed to Leningrad for baptisms, confessions, and communions.

Years passed. The venerable priest grew ever weaker and sicker. His legs barely carried him, and his hands could hardly hold an infant at baptism.

In 1973, he wrote to Archbishop Nikodim (Latyshev) of Moscow, requesting a replacement so that he could retire. But the hierarch replied:

“There is no one to replace you, so I cannot send you into retirement.”

At the beginning of 1983, the priest was bedridden—he had been ill for most of the winter. His health steadily declined. But during Bright Week, he revived. Good news had arrived from Leningrad—the authorities had handed over a former church building to the Old Believer community.

The priest was encouraged. But not for long.

The tireless laborer in the Lord’s vineyard, Father Ilya Blizhnikov, reposed on August 6, 1983, in the arms of his daughter. He was buried in the cemetery in Sysoyevo, next to Anisia Dievna.

The Lykov Family #

In June 1978, geological researchers were searching for iron ore deposits in the upper reaches of the Abakan River. As they flew over the desolate taiga in a helicopter, they spotted a garden and a small hut on the mountainside.

Waiting for a clear day, the researchers set out to visit the mysterious forest dwellers. They approached the hut, which had darkened with age and rain.

The low door creaked. An old man stepped out to meet the uninvited guests—barefoot, wearing a patched and re-patched shirt and trousers.

Silence reigned. Finally, one of the geologists spoke:

“Hello, grandfather! We have come to visit you.”

The old man hesitantly replied:

“Well, come in, if you have come…”

The guests entered the dark hut. Two women were hiding inside. One of them cried out:

“This is for our sins! For our sins!”

The other slowly sank to the floor, clutching a support beam. Her eyes were frozen in horror.

Thus, in the impassable taiga, the family of Old Believers, the Lykovs, was discovered.

In July 1982, journalist Vasily Mikhailovich Peskov visited them. He wrote a book about the Lykovs, Taiga Dead End, which was read by millions of people. Not only the entire Soviet Union but the whole world learned about the hermit Old Believers.

In the 1930s, several families of Old Believers of the Chasovennye (Chapel) persuasion, including the Lykovs, fled into the taiga to escape persecution by the Soviet authorities and to distance themselves from the sinful world. They carried with them icons, church books, and seeds of various plants.

They also brought reserved Eucharistic Gifts for communion and holy water, which they diluted with fresh water as it was consumed. The reserved Gifts were kept in a small, old wooden cask—a sacred relic, a memory of the pious priests from Irgiz, whom the Lykovs’ ancestors revered.

Gradually, the family retreated deeper and deeper into the wilderness. Leading them was the father, Karp Osipovich. His wife, Akulina Karpovna, followed him without complaint, along with their two children, Savin and Natalia. Two more children, Dmitry and Agafia, were later born in the forest.

The Lykovs settled in the taiga, built a hut, and cultivated a garden. They grew turnips, peas, rye, potatoes, onions, and hemp. The turnips, peas, and rye supplemented their diet, though they were not the main sources of food.

They harvested very little rye. The dried grain was pounded in a mortar and, on major feast days, cooked into porridge.

The hermits primarily subsisted on potatoes, which they stored in a cellar. However, even in the cellar, the potatoes would not last long. The Lykovs adapted by making a supply of dried potatoes.

They sliced the potatoes into thin pieces and dried them on large sheets of birch bark or directly on the roof during hot days. If necessary, they finished drying them by the fire or on the stove. The entire hut was filled with birch-bark containers holding the stored potatoes.

Using dried potatoes pounded in a mortar, the hermits baked bread, adding two or three handfuls of crushed rye and a handful of ground hemp seeds. This simple dough, mixed with water without yeast or leavening, was baked in a pan, resulting in a thick, black flatbread.

The Lykovs supplemented their meager diet with gifts from the forest—birch sap, pine nuts, wild onions, nettles, berries, and mushrooms. During the summer and autumn, before the river froze, they caught fish. They ate it raw, roasted it over a fire, and dried it for future use.

Elk and deer roamed the taiga. The hermits hunted them by digging pit traps along animal trails and waiting for prey to fall in.

The catches were rare. But when they succeeded in obtaining meat, the Lykovs feasted—and made sure to preserve some for later use. They sliced it into narrow strips and air-dried it.

Salt was unavailable. This was the greatest hardship of life in the taiga.

“A true torment!” Karp Osipovich would say.

When the Old Believers met the geologists, they refused to accept food from them—even bread and flour. But they did take salt. From then on, they never ate without it.

The Lykovs used hemp to make fabric. They dried the hemp, soaked it in a stream, crushed and combed it. Using a spindle, they twisted hemp fibers into thread, which they then wove into coarse fabric on a simple loom.

Their clothing was of the simplest kind—sack-like garments with holes for the head, tied at the waist with ropes. On their feet, the hermits wore birch-bark clogs. Sometimes, they made homemade leather boots. But more often, they walked barefoot, even in the snow.

In 1961, when their garden yielded a poor harvest and the taiga provided nothing, Akulina Karpovna died from starvation and exhaustion. Her last words were:

“How will you manage without me?”

Indeed, after their mother’s death, the family struggled greatly. She had shared all the burdens of the hermit’s life with her husband—chopping and clearing the forest, planting and digging potatoes, weaving and sewing clothes, fishing, helping to build their log home and dig the cellar.

As a girl, Akulina Karpovna had learned to read church books. She passed this wisdom on to her children. Instead of notebooks, she used birch bark. Instead of ink—honeysuckle juice. By dipping a sharpened stick into the juice, she could inscribe faint blue letters on the birch bark.

Twenty years after their mother’s death, in 1981, nearly the entire Lykov family perished.

First, in October, the youngest son, Dmitry, died from a severe cold.

In December, the eldest son, Savin, passed away. He was the most intelligent member of the family. Through trial and error, he had taught himself how to tan animal hides and sew boots.

Savin was also well-read and knowledgeable in church books. He was firm in matters of faith and opposed the family’s contact with the geologists, believing it to be a sin.

Savin died from overexertion—he strained himself digging potatoes out from under the snow. His sister Natalia nursed him in his final moments. When her brother was gone, she wept:

“I too will die from grief.”

And she passed away a few days later—on December 30, 1981.

Agafia remained in the hut with Karp Osipovich. The two of them lived together for seven more years. In February 1988, the father died of old age.

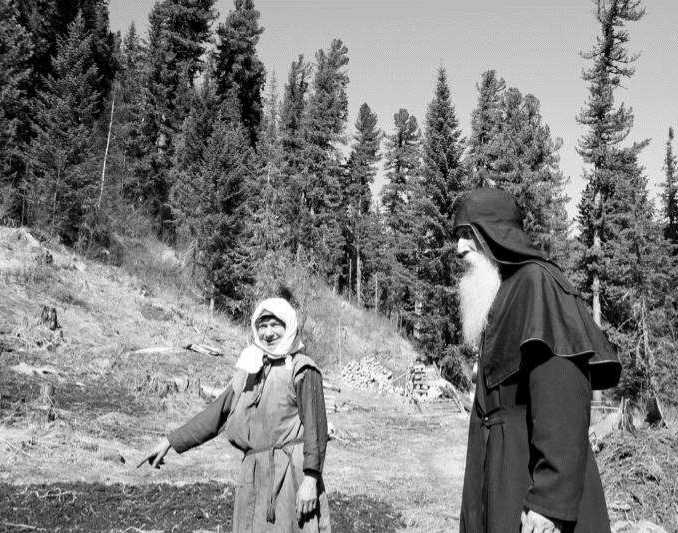

Agafia left her home several times—she stayed with relatives and lived for a while in a Chasovennye Old Believer skete. But she did not get along with them in character or faith and returned to her hut.

The hermitess firmly believes in the eternity of the priesthood and says:

“If the priesthood had ceased, had been interrupted, then the world would have long since come to an end. Thunder would have struck, and we would no longer exist in this world. The priesthood will remain until the very last, second coming of Christ.”

Thus, Agafia’s eventual union with the Old Orthodox Church was a natural step.

In November 2011, with the blessing of Metropolitan Korniliy (Titov), a priest visited the hermitess. He heard her confession and gave her communion.

And in April 2014, Agafia Lykova was visited by Metropolitan Korniliy himself.

Metropolitan Alimpiy #

In a sorrowful time, when it seemed that God had turned away from Christians, on August 14, 1929, in Nizhny Novgorod, a son, Alexander, was born to the Old Believer family of Kapiton Ivanovich and Alexandra Ivanovna Gusev. He would become the future Metropolitan Alimpiy.

His parents were originally from Lyskovo. His father worked as a blacksmith. When they married, a shipbuilding plant in Nizhny Novgorod was being reconstructed, and Kapiton was hired there. It was in the city that Alexander was born.

The family had six children but no permanent housing. After three years, Kapiton and Alexandra had to return to Lyskovo. Alexander Gusev’s childhood and youth passed on the wide expanses of the Volga—wharves, backwaters, the river, and beyond it, fields stretching into the hazy distance, where the wind wandered all summer long, casting shifting shadows of clouds.

During the Great Patriotic War, Kapiton Ivanovich worked at a factory in the city of Dzerzhinsk. At that time, the Old Believer priest Kirill Bushuyev, who was secretly living near the Gusevs, revealed himself to Alexandra Ivanovna and suggested setting up a house church in her home:

“Churches are being allowed again. Permit me to hold services in your house!”

The Gusevs lived in a large two-story home, so Alexandra Ivanovna did not object. The whole family took on the task—removing the stove, arranging an altar and a choir loft. The priest consecrated the house church in honor of St. John the Theologian and began celebrating the services.

In the summer of 1945, the authorities returned a church in Gorky to the Old Believers, which had been closed since 1938. Soon afterward, Bushuyev passed away. Then the authorities told the Gusevs:

“What will you do without a priest? That’s enough—there’s a church in Gorky now. Go there to pray!”

The house church was closed. Now, the Old Believers from Lyskovo had to make a difficult 100-kilometer journey to attend divine services. Among the pilgrims traveling to Gorky for major feasts was the future metropolitan.

In the post-war years, Alexander Gusev first worked as a courier, then as a beacon-keeper on the Volga, and later in the fire department, from where he was drafted into the army. He served for four years in a construction unit.

In 1953, Gusev returned to Lyskovo and resumed his work in the fire department.

His colleagues sympathized with the devout young man:

“Alexander, why have you come here? What are you doing in this place? This is not for you—you should be serving in a church somewhere.”

With the blessing of his spiritual father, Alexander moved in 1959 to the Kostroma village of Durasovo to assist the 85-year-old priest Alexei Sergeev. But he did not stay there long. In 1961, at the demand of the authorities, Gusev had to leave the village. He moved to Gorky, where he took on the duties of a precentor at the church.

In the summer of 1965, the authorities in Gorky closed and demolished the Old Believer church standing on the Volga’s shore. Instead, they gave the believers an abandoned cemetery church.

For the consecration of this church—dedicated to the Dormition of the Most Holy Theotokos—Archbishop Joseph (Morzhakov) of Moscow arrived. He ordained Alexander, who had taken a vow of celibacy, to the rank of deacon.

At the 1969 church council, Deacon Alexander Gusev was deemed worthy of the episcopal rank, but he did not become a bishop until 1986.

By that time, only three elderly hierarchs remained in the Church: Archbishop Nikodim (Latyshev) and Bishops Anastasy (Kononov) and Evtikhy (Kuzmin). Archbishop Nikodim was gravely ill and lived permanently in Moldova, in his native village of Staraia Dobrudzha.

Anastasy persuaded Deacon Alexander to accept the episcopal rank. With the blessing of Nikodim, Anastasy ordained Alexander as a priest in 1985, then tonsured him into monasticism and gave him the name Alimpiy.

Then, on January 5, 1986, Bishops Anastasy and Evtikhy consecrated Alimpiy as a bishop. Unexpectedly, events unfolded rapidly. Archbishop Nikodim passed away on February 11, 1986, and Bishop Anastasy followed on April 9 of the same year.

A council was convened, which elected Bishop Alimpiy as the head of the Russian Church. Thus began the long and arduous revival of the Old Faith.

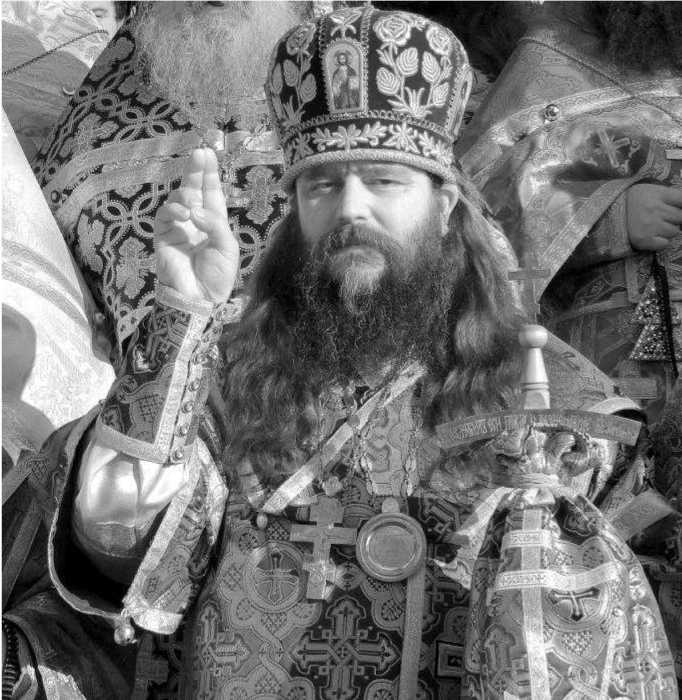

In 1988, during the celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus, Russian Old Believers fulfilled a long-cherished dream—they elevated the Archbishop of Moscow to the dignity of Metropolitan. The decision was made at the 1988 Council, despite attempts by the authorities to obstruct it.

At the same Council, the Church adopted a new name—the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church. And on July 24, 1988, at the Intercession Cathedral in the Rogozhskoye Cemetery, the solemn elevation of Archbishop Alimpiy to the rank of Metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia took place.

Under his leadership, the ranks of the clergy grew, and the number of parishes increased several times over. Many previously closed churches were returned to believers in cities and villages. For example, Muscovites regained the semi-ruined Nativity Cathedral at Rogozhskoye Cemetery. Many churches were also rebuilt from the ground up.

In November 1996, during the 150th anniversary of Saint Ambrose’s joining the Old Believers, a Worldwide Council of the Ancient Orthodox Church was held in the village of Belaya Krinitsa. It was presided over by Metropolitan Alimpiy of Moscow and Metropolitan Leonty (Izot) of Belaya Krinitsa. At this council, Ambrose was officially glorified as a saint.

In 2002, a modern Orthodox bishop, Antony (Hertzog) of Germany, expressed his desire to join the Russian Church. He traveled to Moscow with the priest Mikhail Buk. There, it was discovered that the Germans had not received baptism by triple immersion.

Therefore, they were baptized properly and then reordained. Hertzog became Bishop Ambrose, and Buk was ordained as Priest Mercury. Unfortunately, their stay in the Old Believer Church was brief—by 2007, they had left.

Metropolitan Alimpiy led a strict monastic life. Despite physical infirmity, he strictly observed the monastic rule of prayer. From his frequent making of the sign of the cross, his everyday cassock was worn through at the shoulders.

Presiding over councils, consecrating churches, undertaking long journeys, and constantly caring for the Church took a toll on the Metropolitan’s health. It deteriorated sharply at the end of 2003. The hierarch was sent to a hospital, where he passed away early in the morning of December 31. His funeral took place on January 4, 2004, at Rogozhskoye Cemetery.

Our Days #

In December 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist, breaking apart into fifteen independent states. Today, more than a million believers belong to the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church across these nations. The Church remains one of the largest religious communities in modern Russia.

The Church is headed by the Metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia. His residence is in the capital, at the churches of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery. Each year, church councils are held there, attended not only by bishops and priests but also by laypeople, without whose participation no decisions are made.

After the repose of Metropolitan Alimpiy, the council elected Bishop Andrian of Kazan as the new metropolitan.

Metropolitan Andrian #

Vladyka Andrian—Alexander Gennadievich Chetvergov—was born on February 14, 1951, into an Old Believer family in Kazan. From infancy, he was raised in the faith, enduring mockery from his peers for it more than once.

Chetvergov graduated from the Kazan Aviation Institute and worked as an engineer. In 1980, he married, leading what was, in many ways, an ordinary life.

In 1988, the authorities returned a former church building to the Old Believers, which required restoration. Alexander’s brother, Gennady Chetvergov, was ordained as a priest to serve the newly restored church.

At that time, the engineer left his secular profession to work for the Church. Within the parish, he took on many roles—precentor, driver, welder, carpenter, and roofer.

However, in 1998, his life took a dramatic turn. He was widowed, left to care for a son and two daughters. Chetvergov chose not to remarry, instead dedicating his life to the service of God.

In October 1999, Alexander was ordained a deacon; a year later, he was made a priest. The following year, he took monastic vows with the name Andrian.

In April 2001, Father Andrian was consecrated bishop for Kazan and Vyatka. Then, in February 2004, the church council elected him Metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia.

The new archpastor traveled throughout Russia, visiting many parishes, and also journeyed to Moldova and Ukraine. Metropolitan Andrian was able to establish dialogue with both government representatives and journalists.

This distinguished him from his predecessor. Alimpiy had avoided contact with the outside world and was distrustful of journalists. Andrian, by contrast, willingly met with reporters and government officials, including the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, and Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov.

During Andrian’s tenure, Old Believers entered the internet era. Numerous Old Believer websites appeared, including the official site of the Church, rpsc.ru.

In May 2005, the centennial of the granting of religious freedom to Old Believers and the reopening of the altars of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery churches was celebrated with extraordinary solemnity and grandeur. This event became one of the most significant in church life.

Under Andrian’s leadership, the return of churches confiscated by the communists continued. However, in some cases, local authorities transferred these buildings not to their rightful owners, but to the New Rite Orthodox.

Such was the case in Samara. In May 2004, the former Old Believer church dedicated to the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, which had been closed in 1929, was handed over to the Nikonian Orthodox.

With the metropolitan’s blessing and the support of journalists, Old Believers in Samara began a struggle to reclaim the church. The local authorities obstructed its return to the rightful congregation in every possible way. Only in 2006 was the Kazan church finally restored to the Old Believers.

Unfortunately, Andrian did not live to see this day.

On Wednesday, August 10, 2005, during the Great Vyatka Cross Procession in the Kirov region, the archbishop suddenly passed away from a heart attack.

Metropolitan Korniliy #

In October of that same year, the church council elected a new metropolitan—Bishop Korniliy.

Vladyka Korniliy—Konstantin Ivanovich Titov—was born on August 1, 1947, in the Moscow-region city of Orekhovo-Zuevo to an Old Believer family. After finishing school, he worked in a factory for 35 years, while also studying at night school, a technical college, and an institute.

In 1991, Konstantin Ivanovich became chairman of the Orekhovo-Zuevo Old Believer community. In 1997, he took a vow of celibacy and was ordained a deacon. In 2004, he was ordained a priest. The following year, he was tonsured a monk with the name Korniliy.

On May 8, 2005, Metropolitan Andrian, together with three bishops, consecrated Hieromonk Korniliy as Bishop of Kazan.

Under Metropolitan Korniliy, the great work of Old Believer revival, begun under Alimpiy and Andrian, continues. New communities are being established, new churches are being built, and the preaching of the Old Faith resounds freely throughout Russia.

One of the most important events in contemporary church history was the canonization of Bishop Arseny of the Urals. This took place at the 2008 Council. Then, on September 23, 2011, in the city of Uralsk, his holy relics were solemnly uncovered.

The bishop had been buried in a crypt beneath an Old Believer church that had been shut down by the Bolsheviks. Over time, the crypt became flooded with meltwater. When Christians dismantled the brick vault of the crypt, they saw that the bishop’s coffin was falling apart from decay.

As they lifted the coffin from the grave, the bottom fell away, and it began to collapse. It had to be lowered again. But when the saint’s relics were removed from the coffin, they remained intact.

The bishop’s vestments had disintegrated. His body was covered with what seemed to be a layer of silt. It had not been entirely preserved from decay, but to a significant degree. His head and neck, for example, were completely untouched by corruption—his skin, ears, cheeks, and lips remained intact. His eyes had not sunken in but were closed under their lids.

The relics were carried into the church and placed in a wooden reliquary. Then, on September 25, the Uralsk church was re-consecrated, as it had been in Bishop Arseny’s time, in honor of the Protection of the Most Holy Theotokos.

In November 2011, the church council canonized St. Serapion of Cheremshansk. In the city of Balakovo, construction began on a church dedicated to St. Serapion.

Under Metropolitan Korniliy, great attention has been given to Christian education. The writings of outstanding nachetchiks—Bishops Arseny, Innokenty, and Mikhail—are being published. A theological school operates at Rogozhskoye Cemetery, where a church-historical museum has also been established.

Like Vladyka Andrian, Metropolitan Korniliy meets with high-ranking government officials. On February 22, 2013, President Vladimir Putin awarded him the prestigious Order of Friendship.

The Preaching of the Old Faith #

(From a report by Metropolitan Andrian)

The Old Believer Church strictly preserves the purity of Orthodoxy, strives to carefully fulfill the requirements of the canons, upholds tradition, and brings people the true Orthodox faith and salvation. But today, a question arises: is it enough simply to pray to God, who can Himself grant us all that is necessary for salvation according to our faith?..

Above all, it is essential to fully restore apostolic ministry—both oral and written preaching of the Word of God, and spiritual care for people—both for the faithful and for those who are still outside the true Church.

If, at the beginning of the last century, when the majority of the Russian people were still religious, the efforts of our pastors and nachetchiks were primarily focused on defending Old Belief from the attacks of missionaries and proving the truth and sanctity of the old faith, its ancient books, rites, and traditions against all slander, today Russian society has changed significantly. The majority of people remain poorly informed about the Christian faith, though many still call themselves believers.

Thus, for the Church of Christ, these times are in some ways comparable to the apostolic era: “The harvest truly is plenteous, but the laborers are few.” The time has come for the laborers to hasten to the harvest prepared by God.

To engage in missionary work today, there is no need to embark on distant journeys, venturing into remote lands where people have never heard the Gospel. Such people already surround us in abundance.

Therefore, in every parish, it is necessary to consistently, in the spirit of Christian goodwill and patience, conduct conversations with those who enter the church, even if they come by chance, to tell them about Christ, the Old Orthodox faith, and the historical path of the Old Believers.

But even outside the church, in everyday life, we must not hide the fact that we are Old Believers.

There are no dark or shameful spots in the history of Russian Old Belief. Our neighbors, who live with us in the same house, our colleagues at work, and our classmates in school—each and every one of them should hear from us about our faith.

Metropolitan Leontiy #

The First World War ended in 1918, bringing changes to the state borders of Europe. Not only Russia but also Austria lost its ancestral lands: Bukovina became part of the Kingdom of Romania.

In September 1935, military exercises of the Romanian army took place in Bukovina. They were overseen by King Carol II himself. Together with his entourage, generals, and officers, he visited the Old Believer Metropolitan Paphnutius (Fedoseev) in the village of Belaya Krinitsa.

When the king arrived at the men’s monastery, he was greeted with bread and salt by the metropolitan, surrounded by clergy, monks, and nuns. The honored guest even attended a church service in the monastery cathedral, celebrated by Paphnutius. Later, Carol II visited the bishop’s chambers and, over a modest meal, spoke with him about the state of the Old Believer Lipovans in Romania.

In June 1940, Romania was forced to cede Bukovina to the Soviet Union. The Red Army entered Belaya Krinitsa. The metropolitan left the village, and since then, the throne of the Belaya Krinitsa archbishops has been in the city of Brăila.

That same September, Carol II was overthrown. His young son, Michael I, was declared King of Romania. However, the true ruler of the country became Marshal Ion Antonescu. In 1942, his government began persecuting the Old Believer Church.

The authorities demanded that the Church switch to the Gregorian calendar and begin conducting services according to it, just as the state-backed Romanian Church had done earlier.

Of course, the Lipovans could not accept this. If they had, they would have lost the right to call themselves Old Believers—guardians of ancient Church traditions and the faith of their fathers. The Belaya Krinitsa Metropolitan Tikhon resolutely refused to celebrate services according to the new calendar.

Then Antonescu launched a persecution against the Old Believers. Several churches were closed, and several respected priests and laypeople were sent to concentration camps. The authorities warned that if the Old Believers did not adopt the Gregorian calendar, all their churches would be shut down and all clergy would be imprisoned.

Following a denunciation by Romanian Archbishop Ephrem, Metropolitan Tikhon was also sent to a concentration camp. He remained there for 46 days—until the Soviet Army entered Romania.

Soon, divine justice overtook Antonescu—he was deposed in 1944 and executed two years later.

Thanks to their courage and steadfastness, the Lipovans managed to preserve the Old Russian faith and the sacred traditions of their ancestors. Today, approximately 200,000 Old Believers live in Romania, recognizing the authority of the Belaya Krinitsa Metropolitan. His jurisdiction also includes parishes in Bulgaria, Spain, Italy, Latvia, America, and Australia.

In our time, the Metropolitan of Belaya Krinitsa is Vladyka Leontiy, known in the world as Lavrentiy Terentyevich Izot (Izotov).

The future archbishop was born on August 26, 1966, into a pious Lipovan family in the village of Russkaya Slava. Near the village stands the Dormition Monastery, where the boy often spent time helping the monks and attending the lengthy monastic services.

As a child, Lavrentiy declared to his parents, Terenty and Ekaterina, that he would one day enter the monastery. At the time, no one took his words seriously.

However, the young Christian was firm in his resolve. After finishing school, he served in the army and returned home in 1988. His parents began to speak of arranging his marriage, but Lavrentiy firmly announced his decision to leave for the Dormition Monastery.

In March of that year, the young man moved into the monastery. He lived a strict monastic life, fulfilling various obediences. A year later, Bishop Leonid (Samuilov) ordained Lavrentiy to the diaconate.

In 1990, the young deacon took monastic vows and was given the name Leontiy. A gifted expert in church rubrics and Znamenny chant, he earned the deep respect of the faithful. Every summer, he taught the rubrics and chant to all who wished to learn. Even Bezpopovtsy (priestless Old Believers) traveled to the Dormition Monastery to study under him.

In June 1994, Bishop Nikodim of Brăila and Tulcea reposed. Two years later, the church council elected Father Leontiy to succeed him. And in May 1996, he was consecrated bishop.

That same year, on August 21, the Belaya Krinitsa Metropolitan Timon (Gavrilov) passed away. Once again, a church council was convened, this time to elect a new metropolitan. Preference was given to Leontiy, although many were concerned about his youth.

The solemn elevation of Bishop Leontiy to the rank of metropolitan took place in Brăila on October 27, 1996. The consecration was performed by Metropolitan Alimpiy, assisted by three other bishops.

Following the 1996 World Old Believer Council’s canonization of Ambrose of Belaya Krinitsa, the question arose regarding the discovery and transfer of his relics.

For many years, Old Believers had visited Ambrose’s grave in Trieste. Many times, discussions were held about relocating his remains to another place, such as Belaya Krinitsa. However, for various reasons, this had never been possible.

Then, on May 30, 2000, Metropolitan Leontiy arrived in Trieste, accompanied by a large delegation of clergy from Romania, America, and Australia. The following morning, the Old Believers proceeded to the Greek cemetery, where Saint Ambrose was buried near the church. Italian officials and a gravedigger were already waiting for them.

The Italian began digging but worked slowly. Impatient, the Russians took the pickaxe and shovel from him and set to work themselves. They dug through the hard soil for a long time until, at last, they reached the vault of the crypt. Breaking through, they saw the saint’s burial place.

The coffin had decayed, leaving only its brass handles intact. On the floor of the crypt lay the remains of Ambrose, still clothed in his bishop’s mantle. In his hands was a small hand-painted icon in a metal cover, remarkably well-preserved. The relics had survived in the form of bones, yet the left hand remained incorrupt, with its flesh, skin, and nails intact.

The sacred remains were carefully gathered into a special reliquary and flown to Bucharest on June 3. That same day, they were transported to Brăila and placed in the metropolitan cathedral.

In the years that followed, Leontiy visited Italy many times. Several thousand Lipovans had emigrated there from Romania for work. In 2012, in the city of Turin, the metropolitan consecrated a new church for them, dedicated to Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker.

Leontiy tirelessly visits Old Believer parishes across Europe, America, and Australia. He has traveled to Russia many times and has met with Metropolitans Alimpiy, Andrian, and Korniliy.

Old Believers in Crimea #

The Crimean Peninsula is an extraordinary crossroads, where different peoples have met throughout history. This land has seen them all!

Scythians, Greeks, Goths, Huns, Alans, Khazars, Karaites, Jews, Pechenegs, Polovtsians, Mongols, Tatars—all have left their mark on the region. Crimea is also inseparably linked with the history of Ancient Rus. It was here, in the city of Korsun (Chersonesus), that Prince Vladimir, the holy baptizer of our people, received Christianity.

The Greeks left the most significant imprint on the history of Crimea. Even in ancient times, they founded several cities here, whose inhabitants were engaged in maritime trade, dealing in grain, livestock, honey, wax, salted fish, hides, and amber. It was to these people that the Apostle Andrew preached Christianity.

The true faith spread across the entire peninsula. In earlier times, Crimea had its own Orthodox metropolitan, overseeing numerous monasteries and churches. However, due to frequent and brutal wars, most of Crimea’s Christian shrines have not survived to this day. Today, only their ruins remain.

The greatest devastation came at the hands of the nomadic Tatars. They first appeared in Crimea in 1223. Then, in 1299, their hordes swept through the flourishing valleys of the peninsula with fire and sword. Many Greek cities and villages were burned and destroyed.

Taking advantage of the Greeks’ weakened state, the Italians arrived in Crimea—representatives of two wealthy trading republics, Venice and Genoa. These two cities competed with each other in expanding trade and seizing new lands. Soon, with Tatar support, the Genoese drove the Venetians out of the peninsula.

The Latin-rite Genoese controlled several well-fortified cities along the rocky coastline. The Orthodox Greeks retained a small principality, Theodoro, in the southwestern part of the peninsula. Meanwhile, the Muslim Tatars ruled the steppe interior, where they established their own state, constantly waging war and conducting raids against their neighbors.

The primary occupation of the Tatars was warfare. They conducted brutal raids on neighboring countries, returning to the peninsula laden with rich spoils and numerous captives—strong men and beautiful women. These unfortunate people, having fallen into the hands of the infidels, were turned into slaves and sold to distant lands. Poland and Rus’ suffered particularly from Tatar incursions.

The Genoese and the Turks actively encouraged this inhumane slave trade, which persisted until the mid-eighteenth century. They eagerly purchased fair-haired and blue-eyed Slavic slaves from the Tatars, as such “living merchandise” was highly valued in antiquity.

Captives were transported from Crimea by ship to Genoa and Istanbul. From there, they were sold not only to Muslim states in Asia and Africa but also to Christian Europe—Italy and France. It is estimated that over several centuries, approximately three million people were seized by the Tatars and sold into slavery.

In 1475, the Turks seized the peninsula, expelling the Genoese and destroying the Principality of Theodoro. The Crimean Tatars fell into dependence on the Turks, and the Crimean Khan became a tributary of the Ottoman Sultan.

The local Christian population endured various forms of humiliation. They were subjected to a double poll tax. Additionally, priests were required to host Turkish officials at their own expense. For instance, if a tax collector traveled through cities and villages, he would invariably stay at the home of a priest. The priest was obliged not only to feed the Turk but also to pay a special “tooth tax”—a fee for the inconvenience of the official having to chew coarse Christian food with his delicate Muslim teeth.

The end of Tatar raids, the slave trade, and the persecution of Christians was brought about by Empress Catherine II. In April 1783, she annexed Crimea to Russia. This occurred after several wars with Turkey, which weakened the infidels and provided Russia access to the Black Sea.

In May 1787, Catherine visited the peninsula, accompanied by a grand retinue and envoys from Austria, England, and France. The Empress made a ceremonial entry into Bakhchisarai, the former Tatar capital, and stayed for three days in the Khan’s palace. With this, she demonstrated to the world that Crimea now belonged to Russia.

However, in 1954, the Soviet government took Crimea from Russia and transferred it to Ukraine. Of course, the opinion of the local residents was not considered in this decision. Yet, in March 2014, the Crimean people expressed their will through a general referendum, voting for the return of the peninsula to Russia.

In the eighteenth century, the first Old Believers appeared in the lands under the control of the Crimean Khan—the Nekrasov Cossacks.

At that time, in the Cave Dormition Monastery near Bakhchisarai, the Greek Metropolitan Gedeon resided. Around 1750, he ordained Bishop Theodosius for the Cossacks. Gedeon did this not of his own will but under pressure from the Ottoman Sultan and the Crimean Khan.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Old Believers of the priestly tradition from the Volga region settled in Crimea. On the shores of the Sea of Azov, near the city of Kerch, they established a small settlement called Mama Russkaya.

The Old Believers engaged in fishing, primarily catching sturgeon. They lived very modestly but maintained cleanliness—one of their first constructions in the new settlement was a bathhouse. Their houses were small, built from stones bound with clay. The roofs were made of reeds, which grew abundantly in the area.

Due to the scarcity of fresh water, the Old Believers did not cultivate gardens. Instead, they traded fish for vegetables in neighboring villages.

In May 1913, with the financial support of a local wealthy man named Dirin, a stone church dedicated to the Nativity of the Theotokos was built in Mama Russkaya. The Soviet authorities later closed the church. However, a pious woman managed to save and preserve part of its sacred furnishings.

After the war, the authorities returned the dilapidated church to the Christians. The rescued church utensils were restored to it. Unfortunately, on one occasion, thieves broke into the church, forced open the doors, and stole all the ancient icons. Even now, the community of Mama Russkaya strives to restore the former splendor of their church.

In 2015, a second Old Believer community emerged in Crimea, in Simferopol. The “Russian Black Sea Company ‘Crimean Seafood’” purchased a former church building for the community.

Metropolitan Korniliy visited Simferopol on July 9, 2015. He conducted a solemn prayer service in the new church. It is planned that after its restoration and renovation, the church will be consecrated in honor of the Entry of the Most Holy God-bearer into the Temple.

Old Believers in Africa #

From the Gospel, we know that the angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph, the husband of the Virgin Mary, commanding him to take the newborn Christ and His Mother and flee to Egypt. The Savior was miraculously preserved from the brutal massacre of infants ordered by King Herod. Thus, the Word of God was revealed to the inhabitants of Africa.

According to tradition, the Apostle and Evangelist Mark preached the true faith in Egypt. In its principal city, Alexandria, the apostle established the first Christian community. Mark’s eloquent preaching and the numerous miracles he performed drew many people to God.

From Asia, through merchants traveling from the Arabian Peninsula, Christianity spread to Ethiopia. However, though it bore many good fruits, the tree of the true faith eventually withered on African soil. By the seventh century, the Egyptians and Ethiopians had fully separated from the Orthodox Church, falling into heresy.

Egypt lies in the lower and middle reaches of the great Nile River. In the upper reaches of the Nile was the vast region of Nubia, where three ancient kingdoms once existed—Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia. In the sixth century, the first Gospel preachers arrived there. Later, a special script was created for the Nubian language, and Christian books were translated into it.

From the seventh century onward, the Arabs began their conquest of North Africa. They first seized Egypt and established a powerful state there. Gradually, this state subjugated the Nubian kingdoms as well. The Arabs forcibly converted Christians to Islam, destroyed churches, and burned sacred books. In Egypt, believers in Jesus were reduced to an oppressed and disenfranchised minority. In Nubia, Christianity disappeared entirely by the early sixteenth century. Only in Ethiopia did it remain the state religion.

South of Nubia, at the sources of the Nile and along the shores of Lake Victoria, several pagan kingdoms had long existed. The strongest among them, the Kingdom of Buganda, attracted the attention of European powers—England and Germany. In the nineteenth century, the first European travelers and Christian missionaries arrived in this region.

By the end of that same century, England had conquered Buganda and the surrounding territories. The preaching of the Gospel began to spread freely and widely. Churches and schools were built everywhere. In 1962, a new state, Uganda, emerged in these lands, gaining independence from England.

However, not all Ugandans were satisfied with the version of Christianity taught to them by the English. Many found it distorted. Some, in their spiritual search, turned to the Greek New Ritualists. Thus, in the first half of the twentieth century, communities appeared in Uganda that were under the jurisdiction of the Greek Patriarch of Alexandria.

One of the New Ritualist priests, Joachim Kiyimba (1948–2015), studied in his youth at a theological seminary in Leningrad. There, he learned about the existence of the enigmatic Old Believers. This knowledge later helped him in his search for the true Church.

As he grew older, the priest came to understand that the Greeks had distorted the Orthodox faith, failing to preserve it in its purity and integrity as the apostles and holy fathers had commanded. Joachim and several hundred of his parishioners broke communion with the Patriarch of Alexandria. This came at a high price—their community was left without a church.

Nevertheless, the faithful built a new stone church in Kampala, the capital of Uganda. A school, an orphanage, and a medical clinic were established alongside the church. Kiyimba, who was also a physician, followed the example of the ancient unmercenary saints, treating the poor free of charge.

At the same time, Joachim was searching for a Church that preserved ancient Christianity in its original form along with its unaltered ancient rites. Eventually, he wished to join the Old Orthodox Church. In mid-2012, he began correspondence with Metropolitan Korniliy.

In February 2013, representatives of the Russian Church—priests Leonty Pimenov, Alexey Lopatin, and Nikolai Bobkov—visited Uganda. They met with Kiyimba and his parishioners and were convinced of their firm intention to become Old Believers.

In May of the same year, Father Joachim traveled to Moscow with his wife, Margarita. The Church authorities considered his request to join the Old Believers. It caused both surprise and confusion. Never before had the Old Believers encountered such unusual people. However, after long deliberation, a positive decision was reached.

Joachim Kiyimba was received into the Church through chrismation on May 22, 2013. The sacrament was performed in St. Nicholas Church at Tverskaya Zastava by Priest Alexey Lopatin.

The first black Old Believer priest returned to his homeland. There, great and difficult labors awaited him. He needed to instruct his flock in the old rites, first and foremost, the two-fingered sign of the cross. He had to ensure the beauty of the church, adorning it not with printed icons but with painted ones. He had to replace the abbreviated New Greek liturgy with the full ancient Russian service.

None of this was easy. The parish in Kampala was very poor, lacking funds to acquire painted icons. Moreover, there were no iconographers in Uganda. The local language, Luganda, was little known in Europe, making it difficult to quickly translate liturgical books. English, though the official language of Uganda, was entirely unfamiliar to many native Ugandans, creating additional challenges.

Several times, Old Believers from Russia traveled to Uganda to support their brethren. They brought not only icons, books, and lestovki (Old Believer prayer ropes) for the community but also toys and clothing for the children.

Unfortunately, amid his tireless apostolic labors, Joachim Kiyimba was struck by a severe and prolonged illness. The indefatigable priest passed away on January 10, 2015. The Old Believer parish was left without a priest.

To remedy this dire situation, representatives of our Church traveled to Uganda once again in June of that same year. They sought a Christian worthy of becoming the new priest. In their search, they even ventured into remote areas of the country, where it was unsafe for a white man to appear.

Joachim Walusimbi was chosen to be ordained to the priesthood. At the end of July 2015, he traveled to Moscow to study the Old Rite liturgical practice. After the necessary preparation, Walusimbi was ordained a deacon on September 11 and a priest on September 20.

The new priest departed for his homeland on October 15, 2015, to continue preaching the Old Faith in distant Africa.