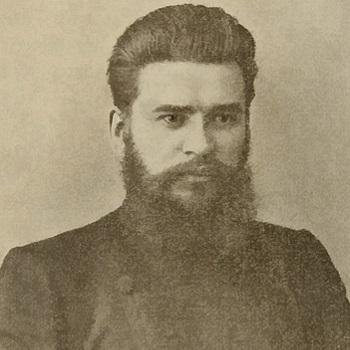

Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin #

A public figure and prominent leader of the Old Believer movement at the beginning of the 20th century, Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was a Russian photographer, documentarian, artist, and owner of a photography studio. He also distinguished himself as a reporter, writer, journalist, publicist, and apologist for Old Belief. The multifaceted nature of N.D. Zenin’s personality was expressed not only in his fluency with theological issues and passionate confession of his faith. Along with like-minded allies and companions, he devoted his life to the struggle for a better lot for the Old Believer community — for freedom of religion, conscience, and the individual; for the purity of the Orthodox faith; and for the cultivation of a cultural environment for Old Believers. Nikifor Zenin was also a book publisher and organizer of libraries. He was elected to the city council (Duma) of the Moscow-region town of Yegoryevsk and served as an elector to the State Duma. He was engaged in charitable work and was a member of the Society for Aid to the Poor, a member of the Yegoryevsk Volunteer Fire Society, and a member of the Voskresensk Volunteer Fire Brigade.

Origins: The Zenin Family and Nikifor #

Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was born in 1869 in the village of Gostilovo, Chaplyzhensky volost, Bronnitsky uyezd, Moscow Governorate (now Voskresensky district, Moscow region), into a peasant, patriarchal Old Believer family. His ancestors, the Zenins, had lived in Gostilovo “from time immemorial,” at least since the earliest written references to the local inhabitants, preserved in cadastral and census records from the 17th century. During the reign of Peter I lived a man named Zenovey (diminutive: Zenya), and his descendants came to be called Zenin. Zenovey distinguished himself in some way, and his name was remembered for a century and a half — up until the abolition of serfdom, when surnames were officially assigned.

According to family tradition, “the Zenin peasants were never serfs.” This tradition is only partially true. For many generations, the Zenins had in fact been serfs under the noble family of the Kustersky. The relationship between the Zenin peasants and their landlords was complex. For reasons unknown, in 1836, eight men of the Zenin family of various ages were granted freedom all at once — including Nikifor Dmitrievich’s uncle, Vasily Ivanovich. By the time Nikifor Dmitrievich was born, the Zenin family was the strongest in Gostilovo. Nearly all the Zenins were literate. The foundation of their prosperity was unceasing labor and avoidance of wasteful and corrupting vices.

Nikifor’s father — the peasant Dmitry Ivanovich Zenin (Oct. 30, 1825 – Nov. 8, 1909) — can rightfully be counted among those whose efforts sustained and developed the nation. He was a great laborer and a capable steward. In addition to their native farming, the Zenins grew apples and engaged in “paper and weaving work.” Beginning in 1853, Nikifor’s father, though still a serf, owned a home-based “paper-weaving factory” with a total of 60 looms and an annual turnover of 7,500 rubles. They wove 1,500 pieces of nankeen cloth per year. The Zenins owned two houses, four horses, two cows, small livestock, and the largest area of leased land in the area. They also ran a shop where they sold manufactured and other goods.

Nikifor was the youngest son. Before him were born four brothers — Ivan (Ioann), Xenophon, Kondraty, and Barnabas — and a sister, Aksinya. In February 1881, Nikifor’s brother Xenophon died; in April of the same year, his brother Ioann died at the age of 31; and on June 16, 1905, another brother, Kondraty Dmitrievich Zenin, tragically passed away at the age of 45. Nikifor had great respect for his father, as evidenced by the inscription on the preserved gravestone:

“Peace to your ashes, great laborer. To you, before the greatness of whose spirit I always bowed, with this monument I fulfill my final duty. Now it is my turn. Your son, Nikifor. Yegoryevsk, October 11, 1915.”

Officially, the Zenins were listed as peasants, but in practice, their family had already begun to rise into the higher social classes of the Russian Empire. It is no coincidence that in the memory of the local old-timers, the Zenins were remembered as merchants. The upbringing of the children was overseen by their mother, Agafya Gavrilovna (1830–1907), “a true Christian.” She taught her son to be truthful, straightforward, and entirely candid. Nikifor Dmitrievich received a good education. He knew several languages: German, French, Polish, Latvian, Esperanto, and all Slavic dialects. He was married to Maria Vladimirovna, a peasant from the village of Gostilovo. The Zenin family, like most residents of Gostilovo, adhered to the Old Christian Orthodox Faith (Old Belief).

Military Service and Arrival in Voskresensk. First Photographs #

At age 21, Nikifor Dmitrievich was drafted into the army. He served in the headquarters of the Sixth Infantry Division. As a soldier, Nikifor Zenin served exemplarily and earned promotion to the rank of non-commissioned officer (feldfebel) and to a class-rated position.

“As a son of my motherland, I personally served both the Sovereign and the Fatherland, served honestly, zealously, as duty demands. For my service in His Majesty’s troops, I received promotions, commendations, and monetary rewards,” he wrote in a 1910 petition to the governor of Ryazan. Upon discharge, he was “publicly told that if all soldiers in the Russian army were like him, the Russian army would be on an unassailable height.”

In 1894, after his discharge from the military, Nikifor Dmitrievich moved to live with his nephew Nazar in the settlement of Voskresensk. By that time, Nikifor Zenin had already mastered the profession of photography. Near the Voskresenskaya station (as he labeled it on his photographs), he established his first photography studio and took his first photographs.

Move to Yegoryevsk. Opening of the Studio #

In 1895, Nikifor Dmitrievich moved to Yegoryevsk. He later recalled:

“I was still a very young man when fate cast me into Yegoryevsk. Raised in a village amid the pure, holy nature unspoiled by the foul breath of modern ‘culture,’ and by a mother who was a true Christian, I did not know real life in its present form. At that time, I thought that it was enough to proclaim goodness and truth to the world, and the whole world would recognize them and bow before them…”

Nikifor Dmitrievich and his wife, Maria Vladimirovna, lived in the Sharapova heirs’ house (as of 1910) on Moscow Street. The fate of their son Mikhail (born 1899) is unknown. It is known that Nikifor’s older brother Barnabas Dmitrievich also lived in Yegoryevsk with his son Alexei. By this time, Nikifor Dmitrievich was already working as a photographer. His earliest known photographs are dated 1898. Over time, N.D. Zenin refined his craft, gained recognition as an artist, and opened the “Workshop of Light-Painting” (Masterskaya svetopisi).

In addition to all sorts of purely photographic work, the Workshop of Light-Painting also produced in small batches and at “very low prices” the following: Visiting-card portraits, Cabinet portraits, and postcards (open letters) with portraits and scenic views. The studio also offered enlargement and retouching of portraits. All these services were performed either from the studio’s own negatives (which were kept in their archives) or from photos and negatives sent in by customers.

Later, he opened another photography studio called “Progress.”

N.D. Zenin became an official member of the Russian Photographic Society in Moscow. Gradually, people began to gravitate toward the young photographer. Portrait cards produced by Nikifor Zenin could be found in almost every household in Yegoryevsk. He left to posterity numerous photographic records of Old Believer life from that era. It was he who photographed many representatives of the Old Believer clergy and church-community figures. Thanks to his efforts, a photographic gallery of Old Believer figures from the Belokrinitsa Concord was created.

Nikifor Dmitrievich not only took portraits of contemporary priests and bishops himself, but also sought out photographs of those he did not know personally. By reproducing both types, he helped preserve the iconography of the Belokrinitsa hierarchy. Zenin’s photo archive was included in the Photo Chronicle of Russia project.

In addition to photography, Nikifor Dmitrievich had another profitable venture: publishing and bookselling. He printed his books only in Old Believer printing houses, since he did not have one of his own. In Yegoryevsk, he owned a book warehouse and shop, as well as a large library. Nikifor Dmitrievich was a highly enterprising man: in addition to various books, he published luxurious photo albums, series of postcards featuring views of Yegoryevsk, and sold various related goods — all of which enabled him to remain financially independent.

Beginning of Public and Ecclesiastical Activity #

While living in Yegoryevsk, Zenin became acquainted with prominent Old Believer hierarchs: Bishop Arseny of the Urals and Bishop Innokenty of Nizhny Novgorod, as well as F.E. Melnikov and M.I. Brilliantov. He deepened his theological knowledge and became a widely recognized nachetchik (expert lay theologian and disputant), an active participant in both public and ecclesiastical affairs. With the start of his public-church involvement, a new direction opened up: photographing Old Believer historical sites, monuments, and figures, and publishing colorful photo albums.

In 1898, as previously mentioned, the imperial government launched a renewed assault on the Old Believers. The Minister of the Interior issued a circular to all governors, ordering them to obtain written pledges from local Old Believer bishops promising “not to disclose their spiritual rank” and even to refrain from performing religious services. Other harsh measures were planned as well. Eight bishops, led by Arseny of the Urals, appealed to the wealthy merchant class for help. Old Believer entrepreneurs quickly responded to the call. The movement was led by the prominent Nizhny Novgorod oil merchant, shipbuilder, and benefactor Dmitry Vasilyevich Sirotkin, who strove with all his strength to fulfill the legacy of his mother — to take up the highly dangerous task of defending the Old Belief.

On September 14, 1900, fifteen authorized trustees from various provinces gathered in Moscow. This assembly came to be known as the First All-Russian Congress of Old Believers. These congresses became annual events. The next eight congresses were held in Nizhny Novgorod at the home of D.V. Sirotkin. Beginning with the third congress, attendance grew significantly. A Council of the All-Russian Congresses was established. Among the participants were young intellectual nachetchiki, including their leader F.E. Melnikov, M.I. Brilliantov, and likely N.D. Zenin. It was decided that they should be part of a five-person delegation sent to the center of the metropolitanate — Belaya Krinitsa — to inform the metropolitan about the state of ecclesiastical and hierarchical affairs in the Russian Old Believer Church and to establish closer spiritual ties between the Church in Russia and the metropolitanate abroad. The delegation was led by Dmitry Vasilyevich Sirotkin and Arseny Ivanovich Morozov. The journey took place in November 1902.

The primary task of N.D. Zenin was to photograph historical monuments, places, and figures of the Old Believer Church. He may also have served as a translator during the journey. Upon returning in 1903, Zenin published the Album of Views of Belaya Krinitsa, Its Churches and Inhabitants… Views of the Greek Cemetery in Trieste… The album consisted of 24 photographs sized 9×12 cm (or 18×24 cm), bound in a luxurious cover. It became extremely popular. Bishop Arseny of the Urals, with whom Nikifor Zenin corresponded, wrote in one letter:

“I thank you sincerely for your distant journey undertaken for scholarly purposes, for the common good through your art.”

Activity in the Brotherhood of the Holy Chief Apostles Peter and Paul #

At the beginning of the 20th century, Old Believer brotherhoods became increasingly active. In 1904, an Old Believer brotherhood was established in Yegoryevsk under the name of the Holy Chief Apostles Peter and Paul, one of the most prominent such brotherhoods in Russia. Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was a member of this brotherhood and, according to F.E. Melnikov, one of its most outstanding leaders.

The brotherhood’s primary objectives were: to struggle against the enemies of the Old Believer Church, to defend Old Belief, and to engage in cultural and educational efforts. They opened schools, organized amateur choirs, held classes in church singing, and published books and pamphlets of a religious-moral and theological-polemical nature. They gave lectures, presented reports, and held discussions on various religious and ecclesiastical-social topics.

The Yegoryevsk Brotherhood maintained a large public library that was constantly replenished with new books. But its most important focus was dialogue and debate — particularly with missionaries of the established Church, as well as with nachetchiki from the priestless factions and other sects. The Brotherhood’s chairman was appointed as the priest of the local church, Father Ipaty Grigorievich Trofimov; Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was appointed as its secretary. He directed the entire life of the Yegoryevsk Brotherhood and mentored young nachetchiki. The Brotherhood was supported by membership dues and private donations. It employed a full-time nachetchik, Vasily Timofeyevich Zelenkov, who became well-known throughout Russia. Other young nachetchiki also worked there, among whom the most distinguished were V.K. Litvinov, G.G. Andreyev, A.P. Ivanov, T.M. Melnikov, and D.E. Ryabov.

1905: The Struggle for Rights and Freedom of Conscience. First Search #

Nikifor Zenin was also known as a passionate advocate and defender of freedom of religion, conscience, and the individual; of the purity of the Orthodox faith; and of the cultural development of the Old Believer community. For this, he was repeatedly persecuted by the police and gendarmerie, subjected to criminal investigations, searches, and arrests.

At the fourth All-Russian Congress of Old Believers, a resolution was adopted to petition the government to unseal the altars that had been sealed in 1856 (during the reign of Alexander II), to allow services at the Rogozhskoye Cemetery, and other requests. Riding the wave of the broader revolutionary movement in Russia, on April 17, 1905 — the feast of the Bright Resurrection of Christ — Tsar Nicholas II signed the Decree on the Strengthening of the Principles of Religious Tolerance, which granted many of the Old Believers’ requests.

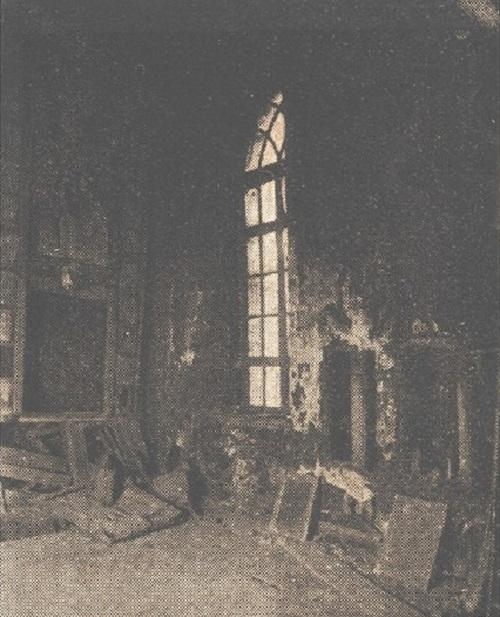

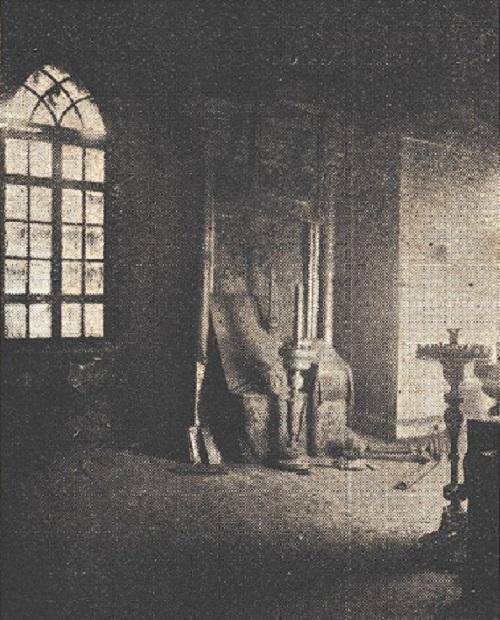

The decree was read at the Rogozhskoye Cemetery on Holy Saturday at three-thirty in the afternoon by Prince D.B. Golitsyn. After the reading, the great wax seals were ceremonially removed. Before the eyes of those gathered appeared a grim sight…

Through the darkness, something terrible could be seen—dust, rot, and collapsed parts of the altar mixed with the rotting floorboards…

Nikifor D. Zenin was likely among the thousands of faithful present. Undoubtedly moved by the sight, he resolved to photograph the unsealed altars for the sake of historical record.

And he was the first to succeed in doing so. Shortly thereafter, he published the album Old Believer Rogozhskoye Cemetery in Moscow in the First Days after April 17, 1905. The format was 18×24 cm, presented in a luxurious gold-embossed folder. This photographic documentation of the Rogozhskoye Cemetery churches in 1905 holds historical value to this day.

Despite the fact that the Decree on Religious Tolerance did not grant the Old Believers even the same rights that had long been available in Russia to other non-Orthodox and even non-Christian confessions—Muslim, Jewish, and pagan—the decree nonetheless inspired hope for better times. N.D. Zenin responded to the decree immediately. Believing in the powerful influence of the printed word, and seeking to promote the Old Belief, he began selling a large number of books “of a tendentious nature.” This was quickly noticed by the gendarmerie, and on May 3, 1905, a search was conducted at Zenin’s premises. “Criminal literature” was found, and the case was handed over to a judicial investigator. However, due to the provisions of the April 17 decree, the case was dismissed. From that moment on, Zenin was kept under constant surveillance.

1905–1907: The Struggle for Rights and Conscience in the Revolutionary Era #

During the revolutionary years of 1905–1907, the political atmosphere in the country changed dramatically. The weakening of censorship, the sudden appearance of hundreds of new newspapers and journals, the convening of the State Duma, and the public discussion of pressing political issues led to the rapid politicization of Russian society. In this climate, Old Believers also felt the urge to enter the political arena and declare their positions.

In 1905, a group of radical-minded nachetchiki (lay theologians and intellectuals) began to form. Among them were the brothers V.E. and F.E. Melnikov, V.E. Makarov, N.D. Zenin, I.K. Peretrukhin, I.I. Khromov, V.G. Usov, I.A. Lukin, and others. They were determined to struggle actively, convinced that the freedoms recently granted could easily be revoked—such things had happened before.

At the Sixth All-Russian Congress of Old Believers, it was planned to discuss “The Position of Old Belief in Light of the April 17 Decree and the Current Situation in General.” However, at the demand of the Nizhny Novgorod governor, the item was removed from the agenda and left unaddressed. Therefore, immediately after the congress ended, without dispersing, the aforementioned group convened a “Private Assembly.”

At the assembly, N.D. Zenin gave a speech marked by moderation and sound reasoning:

“Everyone curses the government and the bureaucracy, pointing out their shortcomings, abuses, and vices, but they themselves are incapable of building anything better or decent. Criticizing is easy—creating is hard. In other countries, rivers don’t flow between banks of jelly either… Therefore, I believe that no constitution, no system of government will help us as long as we remain corrupt and immoral people. Reform yourselves first!”

He was supported by F.E. Melnikov:

“The government has done much evil, but the people themselves—through drunkenness, debauchery, venality, greed, cruelty, and selfishness—have caused just as much harm.”

After the debates, a resolution was adopted stating that:

“The existing police-bureaucratic system does not ensure the stability of decrees, laws, or the rights of man as a Christian and a citizen… It holds back the spiritual and economic development of the people and does not guarantee the implementation of the rights granted to Old Believers on April 17, 1905. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce a national representative body endowed with decisive authority.”

As a result, a comprehensive political program was developed. The assembly concluded with the slogan: “Old Believers of all confessions, unite in the struggle for the right and for freedom of conscience!”

Participation in the Work of the Old Believer Congresses and the Yegoryevsk Community #

Beginning with the Seventh All-Russian Congress of Old Believers, N.D. Zenin was regularly elected to the Congress Council. Among his closest associates in this Council were nachetchiki F.E. Melnikov and M.I. Brilliantov; well-known merchants and manufacturers such as N.T. Katsepov, F.I. Maslennikov, and A.I. Morozov. Also active in the congresses were V.E. Makarov, representing the town of Volsk in Saratov province, and I.I. Khromov from the Yegoryevsk community.

On October 17, 1906, Nicholas II issued a decree to the Senate enacting the Rules for the Organization of Communities by Followers of Old Believer Confessions, and the Rights and Duties of These Persons. These rules were to remain in effect until approved (or rejected) by the State Duma and the State Council as part of the accompanying legislative proposal. That proposal was indeed submitted to the Duma. At long last, freedom had been granted. F.E. Melnikov described this moment as the “Golden Age of Old Belief.” Yegoryevsk became a center of Old Believer life in the southeastern part of the Moscow region and the Ryazan province. N.D. Zenin, half in jest, referred to Yegoryevsk as the “metropolis” of the Ryazan diocese.

From 1907, the diocese was led by Bishop Alexander of Ryazan and Yegoryevsk. Since there was no Old Believer church in Ryazan at the time, the Church of St. George the Great Martyr in Yegoryevsk became the cathedral church, hosting diocesan and local congresses. Archbishop Ioann and Bishop Alexander attended these gatherings. While traveling on church business or for meetings and photographs, Bishops Arseny of the Urals, Innokenty of Nizhny Novgorod, and Mikhail of Canada would stop by Zenin’s home. All of Zenin’s collaborators and fellow laborers passed through there.

In Ryazan, an Old Believer church was built in 1910 with the financial support of the well-known merchant brothers Maslennikov. They founded the community and immediately transferred the church into its ownership at the first meeting. N.D. Zenin rejoiced greatly, even writing an article titled “A Joyous Event.” Based on the decrees of April 17, 1905, and October 17, 1906, the Old Believers of Yegoryevsk established the St. George Old Believer Community, which was officially registered by the Ryazan provincial administration on May 1, 1907.

On May 20, 1907, at the community’s first meeting, its governing Council was elected. The draft law on religious communities prepared by Old Believers began “circulating” through the corridors of power—but it would continue to “circulate” until 1917, and was never adopted.

1917–1918: Religious Readings and Later Involvement

At the initiative of Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin, religious readings were held at the Church of St. George during 1917–1918. Throughout his life, Zenin remained deeply involved in the life of the Old Believer community attached to the Church of St. George in Yegoryevsk. At various times, he was a council member and even chairman of the community. As a delegate of the Ryazan Diocese and the All-Russian Congresses of Old Believers, he participated in the sessions of Holy Councils and was repeatedly elected to the Archbishop’s Spiritual Council. He also took part in delegations dispatched by the Old Believers to ecclesiastical and governmental authorities to address especially important public matters.

Lay Theologian Activity: Searches and Investigations #

Within the church milieu, N.D. Zenin held the special status of nachetchik—a lay expert deeply educated in matters of faith, capable not only of engaging in missionary work but also of defending the Church against its opponents. People from all the surrounding villages would gather for discussions with the nachetchiki. Nikifor Dmitrievich also participated in and led public debates with missionaries.

In 1906, the Old Believer nachetchiki held their first All-Russian Congress. To “combat heresies and atheism,” it was decided to organize the Union of Nachetchiki.

At the Congress, a charter was approved and a governing body was elected, with N.D. Zenin chosen as a member and treasurer. It was resolved that the Congresses would be held annually.

Possessing strong oratorical skills and a combative spirit, Nikifor Dmitrievich adopted the new confrontational style of debate developed by the Melnikov brothers. The following excerpt from the journal Church illustrates his approach:

“On Sunday, November 16, nachetchik V.K. Litvinov joined Union board member N.D. Zenin for a debate in the city of Kolomna with the missionary Father Tsvetkov.”

“In Kolomna, the debate was led by N.D. Zenin… Mr. Zenin, with his usual lecture-like manner of speech, captivated the audience with his reply, vividly exposing the inconsistency between the topic under discussion and the missionary’s speech. He demanded that the missionary not deviate from the subject—if, that is, he truly sought the truth.”

“In a single speech, without the aid of books, Mr. Zenin thoroughly addressed the topic in all its details and declared the debate concluded due to the subject being fully exhausted. The audience was highly pleased with the discussion.”

In 1907, the Second Congress of Old Believer nachetchiki took place.

At the congress, Zenin asked to be relieved of his duties as treasurer and gave a report in his role as nachetchik. At the beginning of his address, he said:

“…As the director of all the activities of the Yegoryevsk Brotherhood and the mentor—according to my own measure of knowledge—of young nachetchiki, I have, for several years now, withdrawn from personal public debates, entrusting them to my students while I myself guide their discussions… But wherever it was possible, I traveled myself to provide direct supervision and observe the work of the nachetchiki. Under my guidance worked the following nachetchiki: D.E. Ryabov, V.K. Litvinov, A.P. Ivanov, G.G. Andreyev, A.L. Lukin, D.S. Varakin, I.A. Spirin-Verkhovsky, and others… The assignments for all local nachetchiki came from me. I supplied them with printed material from the Brotherhood’s library… I personally held many private discussions—with members of the local Nikonian Brotherhood, with their missionaries, and with laypeople interested in questions of religion. The result of my current and past labors has been that the dominant population of our region, once bitterly hostile to us, has undergone a major shift toward sympathy with our confession. This is especially evident among the local intelligentsia…”

He went on to say that the years of emancipation—1905–1907—had greatly benefited the cause of the Old Believer Church, primarily due to the dissemination of underground literature and writings among the people. This undermined the religiosity of the established Church and elevated the stature of Old Belief. By carefully selecting and offering such literature in his bookshop, he was able to effectively propagate Old Believer teachings.

Police Reaction and Investigations #

Zenin’s report drew immediate attention from the authorities. A search was conducted by order of Major General Globa, head of the Ryazan gendarmerie administration, and an investigation was opened. However, due to insufficient evidence for prosecution, the case was dismissed under prosecutorial review. Still, Zenin remained under constant surveillance, and house searches continued, often accompanied by the confiscation of books. For instance, on July 4, 1909, the authorities opened a “Case against photographer Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin for the distribution of illegal calendars (Art. 132).” He had sold five calendars published by Solntse (“The Sun”). Following a written order from General Globa, Zenin’s premises were searched “…for the discovery of illegal literature and any evidence indicating Zenin’s membership in a criminal organization…”

The newspaper Russkoye Slovo (Russian Word) wrote:

“August 1, 1909. Yegoryevsk, Ryazan Province. Mass Searches. In recent days, a number of searches have been conducted in the city among merchants, the intelligentsia, workers, and others. Recently, a search was carried out at the homes of electors to the Second State Duma from the city: A.I. Albitsky and N.D. Zenin.”

On August 29, 1909, a new investigation was opened, but on October 22, the case collapsed without result.

Publication of the Journal Old Believer Thought #

Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was the de facto head of the publishing house Old Believer Thought and of the journal by the same name, as well as one of its founders. The journal Old Believer Thought began publication in 1910 with the active financial support of Zenin. The editorial office was located in Bogorodsk, and the administrative office in Yegoryevsk. The publisher and editor was Zenin’s associate, Vladimir Yevseyevich Makarov, a teacher at the Bogorodsk factory school (of A.I. Morozov).

The subsequent editors of the journal included A.A. Pashkov and I.I. Khromov. This team of like-minded collaborators worked up to the final issue, receiving minimal pay—and often none at all.

In its Address to the Readers, the editorial board announced that the journal was to be inexpensive while also serious in tone, truthful, and completely independent. One editorial article stated that the journal was created to “put into practice broadly Christian and human ideals… to reflect life as it truly is… and to serve in defense of Christ’s Church against enemies attacking it from without and within” (Old Believer Thought, 1910, no. 9, p. 559). On the pages of Old Believer Thought, Nikifor Dmitrievich carried out his campaign against the missionaries of the dominant Church.

One of the main goals of the publication was declared to be the unification of “Old Believer literary and civic forces” (Zenin, N.D. To the Readers, ibid., no. 1, p. 3). As a supplement to the journal, a number of books were issued, including:

-

Excerpts from Patristic and Other Books for the Study of Various Aspects of Church Life by nachetchik V.T. Zelenkov (Moscow, 1911–1912, in three parts);

-

Ecclesiastical and Civil Acts from the Birth of Christ to the Year 1198 by Caesar Baronius (Moscow, 1913–1915, in three volumes);

-

Works of Blessed Simeon, Archbishop of Thessalonica (Moscow, 1916); and others.

Practically every issue of the journal included contributions by N.D. Zenin, who often wrote under the pseudonyms Gostilovsky and Enzet. His articles addressed contemporary issues in Old Believer life, such as:

-

On Gramophones: Church Singing (Old Believer Thought, 1910, no. 9, pp. 159–163);

-

My Impressions from the Consecrated Council of Bishops (1911, no. 9, pp. 746–768; no. 10, pp. 830–837; no. 11, pp. 932–942; no. 12, pp. 1027–1037);

-

The Funeral of N.T. Katsepov (1913, no. 6/7, pp. 558–563);

-

August Conversations in Moscow (no. 9, pp. 849–853);

-

At the Council and Around It (pp. 866–879);

-

Toward the History of the Opening of the Ryazan Diocese (1915, no. 7, pp. 607–611).

Zenin defended Bishop Mikhail (Semyonov) in Seems the Time Has Come… (On the Lifting of Bishop Mikhail’s Suspension) (no. 8, pp. 692–703; separately printed: Moscow, [1915]) and engaged in polemics with the priestless (Bespopovtsy) faction in pieces such as Yes, the Time is Ripening (1912, no. 2, pp. 148–152; no. 5/6, pp. 474–478) and To Our Brethren the Priestless, on the Antichrist (no. 8, pp. 692–703; separately printed: Moscow, 1912).

Despite skepticism from many, Zenin succeeded in making the journal self-sustaining in its very first year.

“…Everyone knows that I live by my own labor, not from the alms of capitalists—neither I myself nor the journal. All subscribers know that I do not publish the journal for profit but help it stand firmly on its feet with my own funds and those of the subscribers alone. And now, less than a year later, I have achieved this. I am confident that its future is secure, and it will be an independent, honest, and truthful organ…”

Nikifor Dmitrievich used donations only to send the journal free of charge—or on credit—to impoverished teachers, clergy, and others.

Among the journal’s many benefactors, Zenin especially highlighted N.T. Katsepov. Any publishing losses were covered from Zenin’s personal funds. The journal was distributed from the Far East to France, and even to Canada—“wherever Old Believer Rus’ still lives.” Zenin served the cause of Old Believer publishing comprehensively. He did much to ensure that the works of the young nachetchik V.T. Zelenkov were published, at least posthumously.

The Struggle for a Truly Christian Society #

Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was also present at every Consecrated Council and was elected three times to the Spiritual Council. Well educated, acquainted with people from all strata of society, and with access to all kinds of literature, Zenin had a strong grasp of politics and foresaw great upheavals approaching. He did not speak of this directly—censorship forbade it. Instead, he expressed his thoughts through grotesque articles or through the theme of the Antichrist. Since the coming of the Antichrist was foretold in the ancient writings of the Holy Fathers, this theme was immune to suspicion and censorship.

Nikifor Dmitrievich sincerely believed that after nearly two thousand years of Christianity, humanity should finally be able to live by Christian principles—by peace and love. Only this, he believed, could avert catastrophe. To the struggle for this vision, he dedicated the best years of his life.

“…People are not angels. One cannot demand too much from them; but within the limits of what is possible, one must strive to elevate one’s life and by so doing call others to follow… Although it must be admitted that people are slow to follow good examples. The vanity of the world is dearer to them: it has seized them in its clutching claws and will not let go…”

He continued his publications, directing them not only to Old Believers but to all people. The titles of some of his articles alone give an impression of this broader outreach: “Our Ancestors and We,” “When Will Man Wake from the Nightmare?,” “The Blessings of True Knowledge,” “The Saddest of the Sad,” “The Source of Living Water,” “How Far It Still Is Until Dawn!,” “Is There Truly No Other Way?,” “Are We Really Like That Too?,” “Those Who Thirst for Living Water,” “What Despair…”

In his article “To Our Youth,” N.D. Zenin wrote:

Old Belief is something very holy—holy in matters of faith, and in daily life, family, national identity, and even statehood. If it disappears, along with it will vanish true faith, the strict and honest Christian way of life, the solid and morally unified family, the uniquely Russian national character—and the state will lose a powerful, cohesive, truly civic force. This is why Old Belief must be supported by collective effort.

And by collective, I mean not only by us Old Believers, but also by the state, and even by the dominant Church itself—because if that Church considers itself Orthodox, then Old Belief is Orthodoxy in its purest form.

In several of his articles, a recurring thought appears: “What is needed is not only, or even primarily, to believe in God (in a relative sense), but to live according to the commandments of Christ and to do good works. Faith without works is dead.”

In 1912, Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin published the article “To Our Brothers the Priestless, About the Antichrist.” In it, he argued that the time for unity had come, presenting the teachings of the Church and systematically refuting his opponents’ claims. To lend persuasive power, Zenin concluded with these words:

“One must not forget that the suffering Jewish people, languishing in captivity and division, endured ancient exile and, even before Christ, conceived of the idea of a coming Messiah (Mashiach) redeemer. Christians believe that this Messiah was Christ. The Jews did not accept Him, and continue to await another. This is why Christ said to them: ‘I am come in my Father’s name, and ye receive me not: if another shall come in his own name, him ye will receive’ (John 5:43). And indeed, it was difficult for the Jews to accept Christ as their deliverer—for they await a deliverer who is a mighty ruler. And another shall come who will give the Jews everything they expect—and they will recognize him as the Messiah. But he will be the Antichrist…”

Esperanto, Participation in the Congress, Arrest and Release #

Nikifor Zenin saw in communication and mutual understanding among all peoples, nationalities, and religions a key to avoiding contradictions and conflicts on Earth. Such a possibility, he believed, was offered by mastery of the international language Esperanto. He studied it and actively promoted it. He conducted extensive correspondence in Esperanto, including with the Old Believer bishop of Ryazan, Alexander (Bogatenko). He joined the Moscow and International Esperanto Societies—Moskva Sosieto Esperantista and Universala Esperantista Asocio—and published a unique series of postcards titled “The Universal Postal Union. Russia” featuring views of Yegoryevsk with captions in both Russian and Esperanto.

“I believe,” he said, “if the brotherhood of nations is to become reality, it will only be when this language (Esperanto) becomes universal…”

In the spring of 1910, he traveled to Paris to attend the Congress of Catholic Esperantists. He went with the blessing of Bishop Alexander, with the goal of demonstrating that the Old Faith was closest to the true Christian ideal. The Congress was held from March 17 to 21. With some difficulty, he obtained the right to speak—and he delivered a report, which was well received.

Upon his return, N.D. Zenin wrote and published a long, fascinating article about the trip in two issues of Old Believer Thought.

In 1913, he took part in the Second All-Russian Esperanto Congress in Kiev. He wrote about the event in Old Believer Thought, issue no. 9 of that year, accompanied by a photograph of the participants. Most likely, he took the photo himself—he does not appear in it. Through his correspondence, Nikifor Zenin seemed to have reached the entire world, writing not only in Russian and Esperanto, but also in all Slavic languages, as well as in German, French, Polish, and Latvian.

In his hands, Esperanto—once little more than a parlor game for elite enthusiasts—became both a language of witness to the truth of Old Belief and a medium of interfaith dialogue.

Zenin’s success at the Catholic congress unexpectedly led to consequences upon his return to Russia. His peaceful trip to Paris proved costly. Soon after, the Ryazan governor, Obolensky, received a letter from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Ecclesiastical Affairs for Foreign Confessions. The letter reported on Zenin’s presentation, noting it had been “very warmly received by the audience.” The department requested from “His Excellency” all available information about “Zenin’s person and his religious-political activities.”

Everything was brought up against N.D. Zenin: his previous sale of “prohibited literature,” the many searches of his home, his speech at the Second Congress of nachetchiki, his supposed ties to Socialist Revolutionaries. Officials declared they were simply waiting for the opportunity to expel him from the Ryazan province.

In July, the police staged a provocation. They sent to him a certain thief, Samsonov, who claimed to want to explain the reason for the repeated searches of Zenin’s shop and apartment. He handed Zenin a note. Suspicious, Nikifor Dmitrievich told him he would only believe it if Samsonov would have his signature notarized. At the end of November, Samsonov returned with the note, now notarized.

Sensing the net closing around him, Zenin used the document to write a petition to the Ryazan governor on December 1. An excerpt reads:

*“Having lived for fifteen years in the province entrusted to YOUR EXCELLENCY and having diligently pursued my trades and enterprises, I have never allowed myself any criminal conduct—neither against private property, nor against public peace, nor against the welfare of the state. I have rejected the teachings of all Russian political parties and, in principle, do not belong (nor intend to belong) to any of them.

Nonetheless, for many years I have borne the terrible burden of relentless searches of my home, the confiscation of books from my shop, the seizure of letters, papers, and so on. I have lost count of the searches. The humiliation I endured has dulled over time and through the numbness of helplessness… Yet the feeling that my inner balance and loyalty are being shaken weighs heavily upon me.

Therefore, I have decided to appeal to YOUR EXCELLENCY for protection, because living this way has become unbearable… And now, by some cruel twist of fate, I am being persecuted as a person suspected of revolutionary intentions.

This statement (from Samsonov), accordingly, is what compelled me to appeal to YOUR EXCELLENCY for protection. I most humbly… request that I henceforth be shielded from those who would attack both my good name and my personal liberty, and that I be allowed to continue peacefully practicing my art and the enterprises to which I am so devoted.”*

The petition had no effect. By order of the secret police, in the night of March 31, 1911, N.D. Zenin’s home was searched, and he was arrested and imprisoned—first in Yegoryevsk, then in Ryazan. A criminal case was opened. Later, Nikifor Dmitrievich explained:

“I was arrested under Article 29 of the Extraordinary Security Statute. That meant I could be exiled to any remote part of the empire without any trial or formal investigation! Of course, I had committed no crime…”

On April 13, 1911, after persistent and determined efforts both in Ryazan and in St. Petersburg, N.D. Zenin was released from the Ryazan provincial prison. His release was secured under a 5,000-ruble surety posted by his supporter, the well-known Ryazan merchant F.I. Maslennikov.

Education and culture – essential conditions for building a better life #

Nikifor Dmitrievich understood that ignorance and lack of education were the chief enemies of a better life, and he knew well the benefits that enlightenment could bring. His speech during the raising of the bells in the village of Yolkino in 1908 is particularly telling. After a few words about the celebration, he said:

“Having completed the building of the church, you must now set yourselves a new task, which must be begun at once. That task is the creation of a school for your children… With all my being, I urge you to devote your full strength to it.”

He then spoke at length about the benefits of education and, in effect, laid out his life philosophy:

“…The teaching of Christ is the only and most perfect of all the world’s systems of belief, against which all scholarly criticism and all philosophical theories, old and new, crash and shatter. Christian doctrine does not fear science and therefore welcomes it. True science will only confirm the truth of the path shown to mankind by Christ… Conscious faith is as firm as stone…”

Nikifor Dmitrievich made considerable efforts to establish a school for Old Believers in Yegoryevsk. The issue was raised repeatedly in the Council of the Old Believer community. On this subject, he even held a conversation with M.N. Bardygin, a member of the Third State Duma. The matter began to move forward only by 1917: the Council had collected nearly 30,000 rubles for its construction. But the revolutions destroyed all plans.

Second only to the study of church literacy, N.D. Zenin valued church singing. On this matter, as well as in other efforts to develop and promote Old Believer culture, Zenin was a close ally of the Bogorodsk industrialist Arseny Ivanovich Morozov. With Nikifor Dmitrievich’s support, the first recordings of church singing (by the Morozov Choir, conducted by P. Tsvetkov) were made on gramophone records. Working with recording firms, he helped not only in the production of these records but also in their distribution and in the organization of singing schools.

As with many innovations, the appearance of records featuring choir singing provoked mixed reactions among Old Believers, dividing them into two camps—supporters and opponents of “praising God with a soulless object.” In the ensuing debate, N.D. Zenin took a firm stance:

“Experience has led me to the conclusion that recordings of church hymns on gramophone records are of great importance. They carry into all the dark corners of our homeland a light that illuminates the darkness of ignorance…”

The full repertoire of hymns recorded onto discs is no longer known. N.D. Zenin’s personal archive was lost after the revolution.

The end of peaceful life #

Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin took an active part in the public life of Yegoryevsk: he was elected as a Member (Glasny) of the Yegoryevsk City Duma; actively participated in charitable work; and received multiple expressions of gratitude, including from the Emperor and from the Yegoryevsk Merchants’ Society. Zenin never gave up his beloved work of photography. He published series of photographs: of religious hierarchs; of the All-Russian Old Believer Congresses; of nachetchiki; of famous paintings by well-known artists; and two series of postcards featuring views of Yegoryevsk, one of which had captions in both Russian and Esperanto.

Then came the First World War. Nikifor Zenin published a long article titled The World Blaze of War, in which he explained its causes in plain language for his readers and expressed his own views:

Something has happened which had not occurred since the foundation of the world: the entire globe has suddenly been engulfed in the blaze of war… Everywhere there is plundering of property by one at the expense of another, everywhere people perish in mutual extermination, everywhere enormous material and cultural values are being destroyed… The future of nations looms large—terrifying in its scale; and what it will become, no one can now foresee… War is a cruel thing, but by the will of Providence, it is now necessary and inevitable. So let us go, brothers, with hope in God, to fight the Germans, that by our trials and our blood we may attain a lasting peace.”

Burdened by these anxious thoughts, Nikifor Dmitrievich erected a granite monument to his father. The tender inscription ends with the words: “…with this monument I fulfill my final duty. Now it is my turn. Your son, Nikifor. Yegoryevsk, October 11, 1915.”

Some time later, in 1916, he was sent to the front with the Second Army by order of the All-Russian Zemstvo Union. His close collaborators were also drafted into military service.

“War must be noble, though implacable: the arrogant German must receive his due, and only then will Europe see lasting peace—once the German menace is completely neutralized,” wrote Zenin.

Closure of the journal Old Believer Thought #

In 1916, financial difficulties began for Nikifor Dmitrievich and the journal Old Believer Thought. Most of the editorial staff had gone to the front. Publication was suspended. But the journal “died” not only because of the hardships of wartime. The true reasons lay almost entirely in a moral shock, a collapse of spirit and energy within Nikifor Dmitrievich himself. He suddenly came to feel that his struggle was in vain, that his efforts had been spent to no purpose.

“Man consciously and finally refuses to cast off the life of the beast and rise to the understanding of the ideal life shown by Christ.”

This destroyed Zenin’s faith in humanity, in his own strength, and in “achieving anything useful for man…”

A deep shock to Nikifor Dmitrievich was also the tragic death of Bishop Mikhail of Canada. The journal ceased to exist. The final issue was published much later in 1917. Its last article ends with the words:

“All the best, dear readers. Until better times. If we live and are healthy—we’ll meet again. If not, then in the next world!.. What difference does it make?.. Only, do not remember us with bitterness!” – N. Zenin

Renewed activity in the Yegoryevsk community and final publications #

With the onset of the war, All-Russian Old Believer activity diminished, and so did Zenin’s participation in it. Instead, he became more active in the affairs of the Yegoryevsk community, serving as its chairman and as a delegate from the Ryazan Diocese to general church Holy Councils. After the death of P.G. Bryokhov, “on Sunday, February 23 (1914, old style), a meeting of the Community Council was held to elect officers. Knyazev V.I. was elected chairman; Knyazev G.S. and Klopov I.F., vice-chairmen; Zenin N.D., secretary; and Demidov A.P. and Volkov P.E., churchwardens.” The affairs of the community noticeably improved from that point on.

In mid-1917, during the days when catastrophic changes had already begun in Russia, the last known work by N.D. Zenin appeared: Trilogies. Christ and Antichrist. It included three parts: “Word One: The Expectations of the Jews,” “Word Two: The Forerunners of the Antichrist,” and “Word Three: The Antichrist.” For some reason, only “Word Two” was published. Whether the other two parts were ever printed remains unknown.

In “Word Two,” N.D. Zenin analyzed all the contemporary political movements, naming foreign and Russian figures—pointing out that most of them were Jewish (curiously, the name of V.I. Lenin is not mentioned in the book)—and concluded that they all preached violence and either denied or diminished the significance of the Church, thus making them “forerunners of the Antichrist.” Although he had once regarded the socialist idea as “even noble,” he now viewed current events with strong disapproval. The primary reason: violence.

He wrote:

*“…I am as far from the deeds of revolutionary parties by conviction as the sky is from the earth. I am not a worshipper of violence, no matter whence it comes or for what purpose. I firmly believe in the truth of Christ’s teaching—that ‘violence begets only violence’ (‘he that taketh the sword shall perish with the sword’). And humanity will be no better off if one violence is crushed by another. That has been my position and will remain so.

Six years of unlawful persecution by the police—right up to imprisonment and the intention to exile me—did not extinguish my faith: that only love triumphs, and violence perishes. And with this faith I shall die…”*

Final years and death #

What little is known of the later fate of Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin comes from the letters of his associate, nachetchik and archpriest D.S. Varakin, addressed to Bishop Alexander and Archbishop Meletiy.

Excerpts from the letters of D.S. Varakin:

“…My move from Moscow to Yegoryevsk, though not without difficulties, turned out to be so convenient and favorable that I could not have imagined it beforehand… Not only was the move smooth, but compared to others, it was even comfortable. We traveled in a separate, though freight, wagon… We traveled a long while—about four days… We arrived on June 28 early in the morning, and I immediately went to Zenin…

…On the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, at N.D. Zenin’s request, three horses and eight soldiers came to the station, unloaded me from the wagon, transported and placed all my belongings in the apartment prepared for me. And so my journey was completed! The community covered the expenses…”

(July 22, 1920, old style)

“…On December 21 (old style), the three of us (N.D., I, and Fr. Kozma) were arrested during a reading and taken to the ‘Political Bureau’… They treated us very politely, did us no harm… My words made a good impression on them, and they released us in peace. And we went home, glorifying God… Whatever God allows is for the better!

During the reading, they seized on some of N.D.’s words about the Jewish religion. True, N.D. had phrased things in a way that could easily be interpreted as criticism of the authorities, but during the explanation it was easy to dispel any suspicion.

He was searched, but nothing objectionable was found. The search was clearly performed just as a formality. They hardly even looked for anything… That’s the whole simple story…”

“…At the general assembly held last Sunday, it was decided to commemorate the late N.D. Zenin in some way, and it was resolved to organize a reading in his memory…”

(February 20, 1923, old style)

“…Yegoryevsk was left impoverished in active workers with the death of the late N.D. Zenin, as though he took all the parish’s well-being with him to the grave. If N.D. were alive, Bishop Geronty (of Petersburg and Kaluga) would not be sitting in prison, and I too would not be under threat…”

(June 17/30, 1924).

Your unworthy and greatly sinful priest, Dmitry Varakin.

From these letters we can conclude that Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin maintained a working relationship with the Soviet authorities and retained a certain degree of respect. In his final years, he focused his efforts on the work of the Community Council. Zenin was profoundly shaken by the 1922 decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee regarding the confiscation of church valuables. Just a few weeks before his death, he wrote to the Old Believer Bishop of Ryazan and Yegoryevsk, Alexander (Bogatenkov; 1907–1928), stating that the seizure by the authorities was stripping the people of their “last hope of salvation in the days of coming disasters—universal impoverishment, universal famine” (Archive of the Metropolis of the Russian Orthodox Old-Rite Church. File 2, No. 101, Sheet 17 verso).

On April 12, 1922, Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin died of typhus. At the time of his death, he lived in Yegoryevsk, Ryazan province, and was registered at 3 Moskovskaya Street, Apartment 6. The death certificate was submitted to the civil registry office by his nephew, Alexei Varnavich Zenin, who lived with him. Maria Vladimirovna Zenina survived him as a widow, remained the proprietor of the photography studio, and continued her husband’s work. Nikifor Dmitrievich was buried at the Nikitskoye Cemetery. The Old Believer cemetery in Yegoryevsk no longer exists; it was located between present-day Futbolnaya and Vladimirskaya streets, in the area of the modern Yegoryevsk shoe factory (according to the Yegoryevsk Historical and Art Museum).

Until his last days, Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin remained a photographer and chairman of the Council of the Yegoryevsk Old Believer community.

This biography was prepared using archival materials from V.N. Zenin, great-grandson of N.D. Zenin.