The Edinoverie

Browse the works of the Edinoverie

The Sacrament of Baptism

Initially, baptisms were performed quickly. A person could be baptized on the same day they came to faith. Later, the practice of catechesis was established—a period of preparation for baptism. Those who had not renounced mortal sins could not be baptized (St. Justin Martyr). Before baptism, the priest conducts a conversation about sins—essentially a confession, but without absolution. The one who baptizes becomes the spiritual father. In the Constantinople Patriarchate, baptisms were performed by bishops solemnly, with a large gathering of people. Catechesis began on the first day of Great Lent and concluded by Lazarus Saturday, when baptisms took place. In the middle of Great Lent, prayers for “those preparing for enlightenment” were included in the Liturgies. During the singing of “As many of you as have been baptized into Christ…,” the catechumens, dressed in white garments and holding candles, entered the church. They received Communion during the Liturgy. Baptisms were also performed on Great Saturday, Holy Pascha (throughout Bright Week), Christmas, and Theophany. By the 12th century, the custom of prolonged catechesis was abandoned (likely because almost everyone was baptized in infancy), so baptisms, according to St. Symeon of Thessalonica, were performed on any day of the year. The devil wages war against catechumens to prevent them from being baptized, which is why exorcism prayers were read over them multiple times (St. Symeon of Thessalonica noted that these prayers were read seven times). Catechumens were required to visit the bishop every Thursday to report on their faith and receive these prayers. Those being baptized must be completely undressed, like newborn infants, as baptism is a spiritual birth. This, of course, poses challenges: for example, in Pakistan, this is an insurmountable barrier for women. Despite the fact that only the priest’s assistant (of the same gender as the person being baptized) is present in the church during immersion, and the priest remains in the altar, waiting for a signal to come out after the person is already in the font, it remains difficult. As is known, “in necessity, the law is applied accordingly,” and one must choose the lesser of two evils. Fulfilling everything literally, for instance during persecution, is an unbearable burden. In countries under Sharia law, where baptizing fully undressed individuals is impossible (and mortally dangerous), leniency may be shown. If a person is seriously ill, every effort must still be made to immerse them. Fr. Vadim shared a case where a sick woman was baptized in a construction trough lined with clean plastic. Four men lowered the woman, lying on a sheet, into this container. Fr. Vadim advocates for everyone to leave the church during the moment of immersion (in my practice, they leave until the baptism is complete). (If a New Rite priest from Gatchina, who was banned from serving after an unsuccessful attempt to immerse an infant three times in the presence of the mother and other relatives, had done this, such a temptation would have been avoided.) The moment of immersion is the culmination of spiritual intensity, requiring the priest’s utmost focus and composure. Nothing extraneous should distract him, and all potential disturbances must be eliminated. A question arises: what to do if a person has no hair to cut (e.g., after chemotherapy)? Fr. Vadim’s answer: in such cases, hair from the eyebrows or eyelashes can be cut, or even fingernails, as a last resort if eyebrows and eyelashes are also absent. Ideally, each person should be baptized in separate water. Fr. Vadim recalls that in Samara, at the RDC church, there were six fonts. Water was consecrated in a large font and then poured into the others, with additional water added. There is a practice where, after each person’s triple immersion, consecrated water is added crosswise to the font, effectively “renewing” it. In Old Believer communities, disputes—sometimes leading to divisions—arise over whether it is permissible to baptize multiple people in the same font. Some argue that since sins are washed away in the water, it loses its power and new water is needed. To opponents who argue that the water is holy, some respond: “The water is holy, but defiled.” This notion, of course, is incorrect. St. John Chrysostom, in his homily on the paralytic, writes that in the Pool of Bethesda, only the first person to enter the water was healed, but now, in the grace of Christ, even if the entire universe enters the font, all will receive spiritual healing in the Sacrament of Baptism. Ancient manuscripts with illustrations show multiple people being baptized in the same font simultaneously. Interestingly, in Greece, rose petals were often thrown into the baptismal font. According to the Great Trebnik, after each immersion, infants are turned over their right shoulder in a circle, symbolizing eternity and providing a necessary shake (this is not specified for adults in the Trebnik). Baptism must be performed in natural, unheated “living” water. It has been observed that if the water is warm, such as in a shallow stream, the child will likely swallow some. However, in cold water, the child’s breath is momentarily caught, preventing choking. Recently, even doctors have noted the importance of immersing infants in cold water to strengthen their immune systems. If it is unknown whether a person has been baptized or baptized by immersion, they must be baptized. After the reunification with Little Russia, where pouring was widespread, local priests petitioned Patriarch Nikon to allow pouring, as they struggled with immersion, even leading to cases of infant deaths. It is known that Novatus, the founder of the Cathar heresy, was baptized by pouring. However, when clergy or laity from his heresy returned to the Church, they were not rebaptized but received through chrismation, retaining their rank (8th Rule of the First Ecumenical Council, 7th Rule of the Second Ecumenical Council). Among the priestless Old Believers, the “Netovtsy” sect includes a group called “Nekrestyaki,” who did not use water at all, only recited Psalm 50, did not pronounce the baptismal formula, and merely placed a cross with a cord on the infant. In 17th-century Russia, as a rule, all non-Orthodox were baptized. Acceptance through the second rite, via chrismation, was extremely rare (used for those baptized in Orthodoxy but later lapsed into paganism or Islam). Patriarch Ignatius was even deposed for accepting Marina Mniszech through the second rite (chrismation instead of baptism). According to Fr. Vadim, it is preferable to baptize an infant on the 40th day, unless they are seriously ill, in which case it can be earlier. The naming should take place on the eighth day at home. In ancient Russia, it was common for the baptized to have two names: one in honor of the saint commemorated on their birth day and another for the saint on the day of baptism (e.g., Prince Ostrogsky, who facilitated the printing of the Ostrog Bible, was called both Vasily and Constantine). Additionally, many had non-Christian nicknames (e.g., Tretyak, Mal). The baptismal certificate must include the date of the person’s name day and a short prayer to their patron saint, so the baptized can pray to their saint. It should be noted that Old Believers do not celebrate birthdays, citing St. John Chrysostom, who wrote that Scripture mentions birthdays only in connection with the wicked kings Belshazzar and Herod the Tetrarch. Among Old Believers, the male name “Seraphim” is not given to laypeople, as there were no saints with this name in ancient times; it refers to an angelic rank. However, some Old Believer monks bore this name. For example, Monk Seraphim, who lived in the 19th century and was glorified for his incorrupt relics, resided in a cave at the Cheremshansk sketes and was a former member of the male Serapion Monastery. A hieromonk named Seraphim also performed the funeral for the deceased Archbishop Anthony (Shutov) at the Rogozhskoye cemetery. Notably, Old Believers do not receive a new name when taking the great schema. After a male infant is presented to the icons of the Savior and the Mother of God, he is brought into the altar and presented to the four corners of the altar (counterclockwise). Female infants, in addition to the icons of the Savior and the Mother of God, are also presented to the icon of the Annunciation (the Mother of God and the Archangel), which substitutes for kissing the holy altar. After this, the baptized must receive Communion (if necessary, with the Reserved Gifts), as it is uncertain whether the infant will be brought to church again or what their future will hold. In Russia, baptisms performed by laypeople were not uncommon. The Greeks did not recognize such baptisms unless performed out of dire necessity. Among us, there were many priestless Old Believers who radically rejected the Synodal Church (referred to as the “dominant confession” at the time). If a baptism performed by priestless Old Believers was correct in form, it was accepted as valid. However, actions performed by impostors—those not ordained but posing as priests or bishops—were not recognized as valid, including baptisms. Baptisms performed by forbidden priests or those stripped of their rank, participating in schismatic gatherings (called “sub-church” groups), were not repeated, as ordination leaves an indelible seal on the soul (see the Catechism). This applies to those baptized by defrocked priests like Fr. Alexander Chernogor and Fr. Leonty Varvarich-Sergeev (Chernivtsi) if they return to the Church. In the Russian Old Orthodox Church (formerly the Novozybkov Archdiocese), there was a period when all actions (marriages, funerals, etc.) performed by priests under bans were repeated. This raises confusion, as, from a canonical perspective, such individuals are considered schismatics. Nowadays, it is common to see four candles fixed to the font before baptism, as is done on a coffin during a home funeral. According to Fr. Vadim, this is an anachronism from the era of persecution when full observance was difficult. He believes it is more correct to place four floor candlesticks at a sufficient distance to avoid interfering with the priest’s actions, especially during immersion, arranged not in a cross shape but around the sides of the font (see History and Customs of the Vetka Church by I. Ksenos). Before the baptismal rite begins, the font should be censed around, followed by those present. If a layperson baptizes out of mortal necessity, after the general opening (from “O Heavenly King” to “Come, let us worship” inclusive), Psalm 50 and the Creed are read, followed by Psalm 31 (three times) after immersion, and then a short dismissal. There are no godparents in this case. Some priestless Old Believers (of the Chasovenny agreement) give the newly baptized a particle of Communion or Holy Water. A layperson, communing in extreme necessity, takes the Reserved Gifts not with a spoon but with the lips (the Gifts are placed on a clean cloth) and then drinks holy water. There is a directive followed by the Chasovenny that receiving the Holy Gifts is preceded by “skete repentance,” several prayers before Communion, and a short absolution (“remit, pardon…”). The Communion is censed with a handheld censer (katsia). An important topic of the meeting was the rites of receiving those returning to the Church from heresies and schisms. There are three rites: the first, the strictest, through baptism—for those “alien to the faith” who distort its foundations; the second, through chrismation; and the third, through repentance. “Roman Catholics” (or more precisely, “Latins”) could be received by the second rite, but since they have entirely lost the canonical method of baptism by immersion, Old Believers receive them through baptism. Patriarch Philaret, at the 1620 Council, particularly insisted on this, stating that the Latins “revived ancient heresies,” echoing the words of the holy martyr Patriarch Hermogenes. Monophysites, such as Armenians, could also be received by the second rite, but in recent decades, pouring baptism has become widespread in their practice. As for priestless Old Believers, out of economy, they are not rebaptized but only have the rites completed—those actions and prayers reserved for priests, especially chrismation. As is known, Old Believers receive those from the New Rite Church, if baptized by immersion, through chrismation and renunciation of heresies. Interestingly, in ancient times, iconoclasts were received only through repentance. In the late 18th century, disputes among Old Believers arose over whether to receive those from the “Nikonians” by the second or third rite. The Kergenets Council (late 17th century) insisted on the second rite, while the “Deaconites,” followers of Deacon Alexander (second half of the 18th century), advocated for the third. Greeks visiting Russia in the 17th century, who temporarily lapsed into Islam and were circumcised after baptism, were admitted to prayer only after 40 days of fasting and chrismation. In cases of mass conversion from heresy or schism, the situation is considered individually, and some leniency is allowed. For example, in overcoming a schism, unity may occur without any rites of reception, as happened recently when the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church (RPSC) and part of the Beglopopovtsy entered into prayerful and Eucharistic communion through the signing of a “Peace Charter.” It is said that they jointly prayed for their deceased ancestors (Old Believers in Romania have not yet recognized this charter, though they maintain prayerful communion with their brethren in Russia). Fr. Vadim cautioned the audience: a priest should not immediately pray with a newcomer without testing their faith, though one should not probe too deeply into an uneducated person. During reception, chrismation should anoint not only the forehead but all parts of the body, as in baptism. According to the Trebnik, the washing of anointed parts occurs on the eighth day, but in practice, it is done immediately. Some adhere literally, not washing for eight days, only wiping their face with damp cloths, which are later burned (they do the same after unction). The rite of renouncing priestless errors was compiled in the late 19th century by Bishop Arseny of the Urals (since the 1960s, it has also been used by the Beglopopovtsy). A question arises: is it possible to change the practice of reception? The answer is clear: if pouring or even sprinkling baptism becomes truly widespread in the New Rite Church, Old Believers may decide at a Council to baptize all those coming from the New Rite. Theoretically, leniency and a shift to the third rite are possible, depending on the correction of anomalies in the New Rite Church, though this is problematic. Among Old Believers of the Belokrinitsa agreement (now called the Russian Orthodox Old Believer Church, RPSC), there were significant disputes after the issuance of the “Circular Epistle” (1860s). Interestingly, when Bishop Arseny of the Urals was asked whether to allow non-Circularists to pray together, he replied: “Since they pray with us, they thereby show that they do not consider us heretics but recognize us as true priests.” In Romania, where most Belokrinitsa Old Believers reside, those coming to Beglopopovtsy churches, though received by the second rite (Fr. Vadim believes they were hasty in this), are not rejected: they may venerate icons, take blessed bread, etc. When traveling abroad for work, they pray together, but upon returning home, they pray separately. Similarly, Old Believer Cossacks, when going on campaigns, often shaved and smoked, but upon returning home, they ceased doing so (otherwise, the elders would scold them).The Sacrament of Chrismation

Chrismation according to the old rite is performed in eleven places on the body, all above the waist (in the post-reform rite, the feet are also anointed). Specific words are said at each anointing. For example, when anointing the forehead: “The seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit, that the shame, which the first man bore everywhere through transgression, may be removed.” St. Cyril of Jerusalem mentions these “invitations” in his Catechetical and Mystagogical Lectures. St. Symeon of Thessalonica calls an unchrismated person an “imperfect Christian.” According to him, it is after chrismation that a person is inscribed in the Book of Life and receives a guardian angel. As is known, priestless Old Believers do not practice chrismation. Fr. Vadim compares their baptism to the “baptism of John,” noting that they do not receive the Holy Spirit. There is a known case from the life of the New Rite Archbishop Luke (Voyno-Yasenetsky), who, while in exile, needed to baptize someone but had no chrism. After some hesitation, he recalled that he is a successor of the apostles, who laid hands on the baptized, through which the grace of the Holy Spirit descended. According to Fr. Vadim, if chrism later became available, such a person should be anointed. If the chrism has thickened, it should be warmed (by placing the vial in hot water for a few minutes). Among the Belokrinitsa Old Believers, chrism was prepared only once, under Metropolitan Ambrose in 1847, in such a large quantity that it still suffices today. This chrism was brought to Russia in cans by Vasily Borisov (referred to as “Vasily Borisovich” by Melnikov-Pechersky). He later joined the Edinovertsy. The Beglopopovtsy prepared chrism three times: in 1925 (Moscow), around 1960 (Samara), and in the 1990s (Novozybkov).The Sacrament of Confession

In the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), so-called general confessions are not uncommon, where sins are read from a book, and penitents collectively respond, “Forgive us, Merciful Lord,” after which they individually approach the priest, who covers them with the epitrachelion and reads the prayer of absolution. Fr. Vadim recalls observing this in Samara in 1991, when, coming from complete unbelief, he went “where everyone goes,” to a Moscow Patriarchate church. The priest poured water on him from a mug, and since he had already drunk tea, invited him to commune the next day. After such a “baptism,” Fr. Vadim testified, he felt no grace and tried to avoid sinful acts only through willpower. However, after immersion, he felt an active strength to combat sins. A priest who refuses to hear a penitent’s confession risks being cursed (Apostolic Canon 52). This can be challenging when mentally ill individuals insist on confessing almost daily. Fr. Vadim shared a case where a woman requested confession, but the priest told her, “Come back in a week when the fast begins.” That night, she died. The priest, with a contrite heart, performed her funeral, as he, not she, was to blame for her dying without repentance. According to the Nomocanon, a priest may take no more than 20 spiritual children. In practice, however, due to a shortage of priests, they may have hundreds, as refusing a penitent’s confession is not permitted under apostolic rules. In ancient times, only bishops heard confessions, later delegating this authority to priests. The Trebnik includes a special prayer for appointing a priest as a confessor. If a spiritual child moves to another area and wishes to change confessors, they must obtain a written certificate from their previous confessor stating they are not excommunicated. The “Rite of Confession” prescribes reading the full order of confession for each penitent, which is practically impossible. Therefore, in Old Believer churches, the opening and closing prayers of confession are read collectively for all parishioners, while the confession itself is conducted individually. Ideally, confession should take place in a separate room with a large window for visibility (rarely, emotionally unstable women may falsely accuse a priest of misconduct). Epitimi (penances) must not be overlooked. For instance, fornication results in excommunication from Communion for seven years (or four, per other rules). According to Fr. Vadim, if an elderly person confesses fornication committed in youth for the first time, it is better not to risk excommunicating them for long but to administer unction and commune them (the same applies to the gravely ill). Only the priest who imposed the epitimia can lift it (even a bishop cannot, except in cases of mortal danger). If a priest fails to impose an epitimia, he will be punished, and the sin may remain unforgiven (see the Life of St. Basil the New, the trials of Blessed Theodora). The penitent is also accountable for choosing a confessor who is overly lenient (see Chrysostom, homily for the 20th Sunday after Pentecost). For those not admitted to Communion after confession, separate prayers are read, omitting words of forgiveness and absolution. Those barred from Communion may partake of holy water (a deacon may administer it if necessary). As preparation, they read the proper canons (omitting Communion prayers). Interestingly, St. Joseph of Volokolamsk gave unconsecrated prosphora to those temporarily excommunicated from Communion for consolation. Epitimi should be feasible, considering age, health, and level of church involvement. It may be reduced based on the person’s correction, dietary restrictions, fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays for those who do not fast, etc. Epitimi is not punishment but a remedy, a trial period. In mortal danger, a person may be communed, but upon recovery, they must continue the epitimia. A priest who is not the person’s confessor may commune them only if they are dying (even if excommunicated by a bishop). Only a bishop who has illegitimately seized another’s see cannot be communed, even in mortal danger. Fr. Vadim spoke of the need to combat intrusive thoughts and the benefit of keeping a diary to record sins (St. John Cassian the Roman). He offered a vivid analogy: “We cannot stop a bird from flying into our garden, just as we cannot stop thoughts from assailing our soul. However, we can prevent the bird from nesting in our garden, just as we can prevent thoughts from taking root in our soul and turning into actions.” Monk Pavel of Belokrinitsa kept such a diary, preserved in the Belokrinitsa Monastery archive. This archive was taken to Russia by monks who joined the Edinovertsy. Professor Subbotin published it, though not all his writings are favorable to Old Believers, but their hierarchy’s apostolic succession is undeniable. Spiritual children cannot switch confessors without extreme necessity. A confessor should, in principle, be permanent, except if the spiritual child relocates. In ancient times, a priest hearing confession would place the penitent’s hand on his neck, saying, “Child, may your sins be upon me.” If a spiritual child disobeys the confessor or fails to fulfill epitimi, the confessor must part ways with them to avoid sharing in their sins and perishing (see Great Trebnik, preface to the rite of confession). One should avoid choosing a confessor younger than 40, as until that age, a person’s soul is a “plaything of demons” (Nomocanon).The Sacrament of Marriage

According to the 72nd Rule of the Sixth Ecumenical Council, a marriage between an Orthodox and a non-Orthodox must be dissolved (except when the non-Orthodox party promises to convert to Orthodoxy). Marriage law is complex. Blood and spiritual kinship must be observed up to the eighth degree (in the New Rite Church, per a Synodal decision, up to the fourth degree). Marriages must not be conducted secretly and should occur only within the couple’s community. The upcoming marriage is publicly announced from the ambo weeks in advance to allow parishioners to report any impediments. Couples must not be married without confession and the aforementioned “marriage inquiry.” A priest should not marry someone else’s spiritual children. If the couple has different confessors, both priests must agree on the marriage. Ideally, the couple should have the same confessor before marriage. If a priest refuses to separate from an adulterous spouse, he must be defrocked. In ancient times, a widowed priest either took monastic vows and entered a monastery or ceased serving in his parish (praying only at home). The priest replacing him was required to provide for him (giving a third of his income). This was because widowed or single clergy risked parishioners, particularly women, developing feelings for them, requiring great caution. The best option was to take monastic vows. Priests can encounter unexpected situations. Fr. Vadim shared a humorous case: “Before the revolution, in the Urals, a priestless community joined our Church. They sent a good priest, but they expelled him. Another, even better priest was sent, and he was also expelled. Then a heavy drunkard was sent; he barely served, didn’t read the rules, and gave no sermons. Yet, he was accepted. Why? It turned out an elder in the community lifted the cassocks of candidates with a stick, and since the first two wore European-style trousers, they were deemed unacceptable.” If one spouse refuses physical intimacy for three consecutive years, the marriage may be dissolved for this reason. In Novozybkov, a marriage was dissolved the day after the wedding due to the husband’s inability to consummate it. Later, however, this man raped an elderly woman. Conclusion: if there is suspicion of inability to consummate, divorce should not be rushed; at least three years should pass, as required by sacred rules. If a husband is missing for five years and his wife remarries, she must return to him if he reappears. A wife has the right to divorce if her husband forces her into perverse forms of intimacy. The party responsible for a divorce cannot enter a new marriage. Some suggest that, in extreme cases, the guilty party may marry after 15 years, having fulfilled epitimi, but this practice does not exist in the RPSC. During the wedding, neither the priest nor anyone else should step on the white cloth on the floor, which is reserved for the couple as a symbol of their union’s purity. If a priest marries those closely related by affinity, knowing of the relation, he must be defrocked.The Sacrament of Unction

In the Sacrament of Unction, minor and forgotten sins are forgiven for the sick, but it cannot replace epitimia for mortal sins in healthy individuals. Those barred from Communion are not anointed, except in cases of mortal necessity. During the sacrament, seven candles are used: either one is lit before each anointing (as per the Great Trebnik), or all are lit at once and extinguished one by one after each anointing (customs vary). Some priests, during mass unctions, read two Gospel passages designated for men and women, while others, when both genders are present, read the 14th section from the Gospel of John (before the first anointing) and then the Gospel passages for men’s unction for subsequent anointings. If the anointed person dies, the remaining consecrated oil (separated from the wine) is kept in a vessel until the 40th day. If the person dies within this period, the oil is poured over the body at the end of the funeral rite. This oil is not used in food. If the anointed survives past the 40th day, the oil (and wine mixed with it) is burned in a lamp. There have been cases of miraculous healing after unction, and it almost always brings relief from illness.The Sacrament of Communion

If a person is dying, a priest must drop everything and rush to them, even uninvited. If he does not make it in time, it is God’s will. If the call comes during a service, such as during the proskomedia, the service should be paused, filled with a reading or exhortation, and the priest should hasten to the dying person’s bedside. There are cases where a person dies immediately after Communion, and others where they revive. For instance, when Fr. Valery Shabashov was speaking with Archbishop Nikodim (Latyshev) (†1986), the latter suddenly collapsed. Everyone fled in fear, but the priest hurried to commune the bishop, who then revived. Another case occurred in the RDC church in Samara. A group of believers prayed all night in the church before Communion. During the service, a woman suddenly collapsed, with no pulse, breath, or heartbeat. In such cases, one or two strong blows to the lower sternum can often restart the heart. The woman regained consciousness, was communed, and was taken to the hospital. According to Fr. Vadim, being in a coma is not a reason to withhold Communion. Such individuals, to the surprise of doctors, may swallow. They may regain consciousness or even recover—such miracles occur. If a person lived a Christian life and desired confession, they should be communed. However, if they rejected the Church and did not repent, they cannot be communed. In any case, no one should be communed against their will, even in a coma. I would like to note that the value of Fr. Vadim’s teaching lies in the real-life examples he provided. A priest, in his view, must take all measures to encourage a dying person to confess and commune. However, if these efforts fail, the priest is not entitled to perform a funeral over that person. Once, Fr. Vadim visited a one-room apartment where a dying man lay on the floor among cabinets. He was conscious but responded to the priest’s offer of confession and Communion with: “Get out, priest, I don’t recognize you.” Three days later, he died, and no Christian funeral was performed. Another case involved a woman in a village living with her sick son. She died without confession. Fr. Vadim approached her house and knocked on the gate. “What do you want?” He explained his purpose. The response: “We don’t need anything, everything’s fine—go away.” He left, but the next morning, the woman’s niece came, reported her death, and asked for a funeral. She explained that it was not relatives but a neighbor with Old Believer roots, who read prayers over all deceased indiscriminately, who had refused the priest to avoid losing payment. Fr. Vadim had to read the canon of St. Paisius the Great for those who died without repentance at the woman’s coffin in the church. He concluded that God brings the worthy to Communion in any case. Another incident involved a dying chanter. Fr. Vadim could only arrive in the morning and suggested that a nearby deacon administer Communion. The woman adamantly refused, saying, “No, only you.” When the priest arrived, she had died half an hour earlier. According to Fr. Vadim, if a person fails to confess and commune due to the priest’s fault, they can still be given a funeral. A priest must respond immediately to calls to confess and commune the dying. In this regard, I would note the difficulty in Moscow, where many hospitals have churches and assigned priests. When someone asks me to commune a patient in a hospital, I always ask if there is a church and priest there. It is crucial not to delay, to get an answer quickly, and to act based on the situation. The attitude toward written confessions sent by mail is ambiguous, permissible only in great necessity. Absolution prayers in such cases are read remotely. If a layperson hears a dying person’s confession in the absence of a priest, they must convey its contents to a bishop. Some hold a superstition that confession or unction for a gravely ill person hastens death. As is known, in ancient times, the Liturgy was served with one prosphora without an image on it. There was a period when six prosphoras were used (16th-century handwritten service books). By the time of the reforms, seven prosphoras were used, though besides these liturgical prosphoras, there were also private ones. There was no need to criticize the established practice, which carried deep symbolism. In the chapel where the Liturgy is to be served, the full cycle of daily statutory services must be performed. No more than one particle may be taken from a single prosphora, just as one cannot be baptized or ordained twice. A lamb is slaughtered once; slaughtering it again would be over a corpse. The wine for the Liturgy, as is known, must be grape wine. During the Time of Troubles, Jesuits blocked its supply to Russia to halt the Liturgy. The Zemsky and Local Council then decided to use cherry juice. As soon as this became known, grape wine supplies to Russia resumed.The Sacrament of Holy Orders

Judgment in the Church belongs solely to bishops—they make decisions either alone or in consultation. A deacon is judged by three bishops, a priest by seven plus the metropolitan, and a bishop by twelve plus the metropolitan. If a clergyman is unlawfully stripped of his rank but continues to serve, an appeal is not possible. It is known that among Old Believers, a bishop is elevated to metropolitan rank through a consecration. This was the case with Nikon when he was elevated to Patriarch. The Greeks criticized the Russians for this, but it was the Greek Patriarch Jeremiah who consecrated the first Russian Patriarch, Job, in this manner. According to Fr. Vadim, since this precedent exists, there is no need to question it. The canons prohibit ordaining someone to the priesthood twice, as a second ordination would imply the first was invalid. However, in this case, the elevation complements rather than negates the prior ordination, so it does not fall under this rule. Regarding a priest ordained after committing fornication, Fr. Vadim noted that all his sacramental acts are valid, but he himself “burns” (i.e., faces spiritual consequences). Church law strictly regulates accusations against clergy. Accusers must provide written confirmation that they are aware of the consequences. A layperson making a false accusation may be excommunicated. They must personally appear in court, and anonymous accusations are not accepted. Witnesses must not be excommunicated from Communion, must not be in an unblessed marriage, and must be churchgoing. Close relatives, those dependent on the accused or accuser, or those previously convicted of perjury cannot be witnesses. If one accusation is unproven, further accusations from that accuser or witness are not considered. Witnesses must have personally seen what they testify to, not rely on hearsay. Two or three witnesses are required to accuse a cleric, and five for a bishop. Audio, video, or photographic evidence is questionable due to the possibility of manipulation. For a layperson publicly accusing a priest, even if true, the canons assign them to “Judas’s place,” resulting in excommunication (Nomocanon). The trial must be in person. The accused is summoned three times with the charges presented by two peers of equal rank (e.g., Fr. Alexander Chernogor, stripped of his rank in the RPSC, was summoned multiple times). During the investigation, the priest should not be barred from serving. In cases of community conflicts or accusations against priests, the Metropolitan Council forms a commission to hear both sides and seek reconciliation. Minor violations may result in a reprimand, but grave sins are handled through a special procedure. Family conflicts are particularly challenging. Once, Archbishop Gennady (Novozybkov) attempted to reconcile a couple, but they united against him, and the husband struck him on the head. After this, the bishop vowed never to intervene in marital disputes (a similar story is found in the memoirs of Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechayev) – Igumen K.). A priest must serve continuously; failure to serve for three consecutive Sundays without valid reason results in deposition. Those who do not commune during the Liturgy partake of the antidoron, but only if not excommunicated. Excommunicated persons cannot offer prosphoras for the first few years of their excommunication. If a confessor, due to ignorance or weakness, recommends an unworthy candidate for ordination, they face the strictest accountability. Given the heavy burdens and constant stress of priestly service, candidates must provide medical certificates confirming mental health. Those who have committed voluntary or involuntary manslaughter, such as killing someone in a car accident, cannot be ordained. Candidates who are quick-tempered or lack self-control, who have not preserved their virginity, or who are married to non-virgins or actresses are also ineligible. If a confessor blesses a spiritual child with carnal sins for ordination, both the confessor and the ordained, though their sacramental acts are valid, “burn” in the afterlife, facing a dire fate (Nomocanon). A priest must not shave facial hair, trim mustaches (like laymen), or cut head hair. In contrast, Moscow Patriarchate clergy must trim mustaches to avoid interference during Communion (Old Believer priests twist their mustaches during Communion). Those who bite their mustaches are called “self-eaters.” Christ did not cut His hair. Apostolic depictions show some with long hair (e.g., Apostle Andrew) and others with short hair (e.g., Apostles Peter and Paul). In ancient Russia, priests and monks shaved a circle on their heads (“gumenzo”), renewed every 40 days. In Constantinople before its fall, long hair was worn by officials, and afterward, priests began growing it. Protopriest Avvakum had long hair, so this is not a Nikonian innovation. Fugitive priests joining Old Believers from the dominant Church also had long hair. Until the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Synodal Church priests wore skufias, later replaced by hats, which they retained when joining Old Believers. In Romania, Old Believer priests typically wear long hair. The Kazan-Vyatka Diocesan Council in the 19th century permitted priests to cut their hair due to persecution. The 1922 RPSC Holy Council ruled that while cutting hair is not sinful, it is preferable for priests to grow it. Beglopopovtsy and Old Believer clergy in Romania strictly adhere to this custom. Fr. Vadim noted that opinions vary on this issue, and it is not worth arguing over. Interestingly, Metropolitan Dimitry of Rostov ordained several individuals who later joined the Old Believers and were accepted in their existing rank. Not all agreed, leading to a schism in Vyatka. From the Prologue, we know that when a deposed priest, bound under the altar, served the Liturgy, a radiant angel in white vestments served “for the sake of the faith of those present.” The Nomocanon states that grace acts through all priests, but woe to those who are unworthy instruments.Burial

Fr. Vadim leans toward considering burial a sacrament, not as a separate one but as the completion of the Sacrament of Repentance. Burial is surrounded by many superstitions, such as the belief that relatives should not wash the deceased’s body or carry the coffin. This may be promoted by funeral service workers seeking profit. Old Believers ensure that everything in the coffin decomposes (“dust you are, and to dust you shall return”). Even the pectoral cross was preferably wooden, not metal (hence archaeologists’ confusion about whether a burial is Christian if no metal cross is found). Deceased men were dressed in knee-length shirts, belted, with trousers and light footwear (nogavitsy), and a lestovka on the left hand. Both men and women were wrapped in shrouds (the face covered after the funeral). A written note with the spiritual father’s name was placed in the right hand, folded in the two-finger sign, even if another priest performed the funeral with the spiritual father’s consent. The paper crown (venets) was secured with a ribbon around the head. During the funeral, the coffin was covered with a velvet or brocade church cloth (as seen in a photograph of Bishop Arseny of the Urals’ funeral; in recent years, Old Believers have begun covering deceased bishops’ coffins with an episcopal mantle, possibly a New Rite influence? – Igumen K.). Oil is poured on the body itself, not the covering, in the shape of an eight-pointed cross (vertical line, then the longer middle bar, lower bar, and upper bar). If no unction oil is available, lamp oil from the altar is used. The vessel containing the oil is buried with the deceased at their feet. Such vessels are found in ancient Russian burials, including one found at the feet in the coffin of St. Arseny of the Urals’ relics, likely to prevent sorcery. If the priest does not go to the cemetery, before closing the coffin lid, he sprinkles earth on the covering, saying, “All is from the earth, and all returns to the earth…” If no priest is present, laypeople led by a reader escort the coffin with appropriate hymns, and the priest performs an absentee funeral. In the absence of a priest, readers poured oil on the body, likely not crosswise, and placed the written note in the deceased’s hand. For monastic burials, 40 candles were lit. On the way to the cemetery with a monk’s coffin, three stops were made for memorial litias (in Romania, Old Believers stop at crossroads for laypeople’s coffins). Throwing handfuls of earth into the grave, Fr. Vadim suggests, may be a pagan remnant from mound-building, but he sees no sin in it, as gravediggers do the same with shovels. Artificial flower wreaths are also a pagan remnant and undesirable, but it’s better not to object during burial to avoid disputes, especially since people attach no symbolic meaning to them. Fr. Vadim recounted the funeral of a prominent merchant and philanthropist Maltsev in Balakovo, Saratov Province, described in an Old Believer journal as “Unprecedented Funeral.” Photos showed the coffin covered in flowers, and for 40 days, the entire city was fed twice daily in the deceased’s memory. For absentee funerals, the service is performed before kutia, with honey symbolizing the sweetness of the life to come. Alcohol at memorials is prohibited to prevent them from becoming revelry. The issue of funerals for those who died suddenly is complex. It differs if death was sudden versus, for example, a drunk person knowingly risking danger and drowning while crossing a river, making them a suicide. A memorable case involved a young man, the son of a woman who, despite warnings, did laundry on the eve of St. Nicholas’s feast and drowned after falling off a cliff. Witnesses said he walked as if entranced, hands at his sides, toward his death. Old priests commemorated their spiritual children daily, specifically for repose, not health. Commemoration on the 40th day is strictly on that day, but on the 9th day or anniversary, if they fall on major feasts, it is moved to Saturday (except Lazarus or Great Saturday).On the Blessing of Water at Theophany

Regarding the blessing of water on Theophany Eve and Theophany itself, there is still no consensus on all related issues. St. Maximus the Greek wrote that under Patriarch Photius (9th century), a water blessing “in the August manner” was performed at the start of each month, and in January, on Theophany (he does not specify the rite’s prayers). Patriarch Nikon abolished one of the blessings. Now, in New Rite churches, water is blessed twice, both times as a great blessing. Bishop Arseny wrote: “I am not certain, but I think the great blessing of water should be performed on Theophany Eve, and on Theophany itself, a lesser blessing with the same rite.” Several 16th-century handwritten Trebniks state that on Theophany Eve, the lengthy prayer (“Great are You, O Lord, and marvelous are Your works…”) in the Great Blessing of Water is read aloud, while the second lengthy prayer by Patriarch Sophronius is omitted. In the second blessing on Theophany, the second prayer is read silently, followed by the first aloud, and the third is omitted—this is the main difference. Essentially, on Theophany itself, a lesser blessing of water is performed. Bathing on Theophany was practiced by Old Believers in Saratov relatively recently, with even priests immersing. Immersion in the Jordan was common in earlier times. The canons do not forbid it, so there is no sin, but Christian decorum must be observed. On Liturgical Vestments Fr. Vadim’s explanation of vestment symbolism was fascinating. The epitrachelion (in New Rite, epitrakhil) recalls the rope by which Christ was led to Golgotha and symbolizes the grace poured upon the priest. The belt represents the strictness of Old Testament law, with its four pendants (“sources”) symbolizing the grace and freedom in Christ, the New Testament flowing from the Old, and the four Gospels. The belt bears a four-pointed cross (“shadow cross,” prefiguring Christ). Each pendant has three eight-pointed crosses, totaling twelve, symbolizing the twelve apostles. The cuffs symbolize Christ’s bonds. Previously, all priests in Russia and Romania had seven buttons on their cuffs. Since the mid-20th century, under Archbishop Flavian (Slesarev), priests and hieromonks have seven buttons, representing the seven sacraments; proto-priests and archimandrites have nine, symbolizing the nine angelic ranks; and bishops have twelve, for the twelve apostles. In ancient times, bishops wore crosses and panagias only while traveling, not during services. The diamond shape at the bottom of the felon symbolizes the world (four ends) and the four evangelists. Fr. Vadim’s information on the peculiarities of the Rite of the Panagia was noteworthy. Candles must be wax, like Abel’s pure offering. Paraffin candles are likened to Cain’s offering, mixed with chaff. During Khrushchev’s time, churches used olive oil, but later, sunflower oil became common. Wicks in vegetable oil must be halved in thickness, as they swell and hinder burning. Conclusion Studying liturgics and pastoral theology at the Moscow Theological Seminary and Academy, I likely gained less than from Fr. Vadim’s two lectures (or discussions), which lasted about 13 hours in total. What was lacking in the theological schools? Concrete, living examples and an overly schematic, scholastic presentation of material. Liturgics was given insufficient weight among the disciplines, though it is crucial for future pastors. There were interesting moments in the lectures of the late Protopriest Gennady Nefedov and Archimandrite Matthew (Mormyl), especially in Fr. Damian Kruglik’s course on practical pastoral guidance. But Fr. Vadim, sometimes called a “walking encyclopedia,” offered something unique. I recall the pastoral theology textbook from my studies (1980–1987), two-thirds of which consisted of long quotes from Old Testament prophets condemning negligent pastors—important, but insufficient. May God grant that Fr. Vadim delights us with a series of books on liturgics, which would be an invaluable aid for altar servers. sourceThe development of church theology in ancient Russia still awaits its historian. Despite the extensive research devoted to contemporary events in church and civil history, the evolution of Christian legal and moral concepts within our own land remains poorly studied. The flourishing of Christianity in Russia long before St. Vladimir is clearly attested by Blessed Jerome and some of the earliest Arab writers. Besides the well-known accounts of the preaching of St. Andrew the First-Called, there is evidence that under pagan emperors, the bishops of Jerusalem had ties with southern Russia and preached here. It is reliably known that Constantine the Great and John Chrysostom took an active part in the planting of the Christian faith on Russian soil, among the “Rosses.”

Christianity made its way into Russia by three principal routes: through the Caucasus and the Black Sea from Syria, Palestine, and Egypt; through Constantinople from Greece; and from the west via Italy. The strength and significance of these influences are difficult to judge now, but it is certain that each had its own distinctive coloring. After the Greek influence, the strongest was the eastern, that is, Syrian-Palestinian. Among the legends found in the oldest Slavonic manuscripts, there are many that do not appear in the earliest Greek sources—these are translations from Armenian, Syrian, and Coptic. This eastern influence was probably older than the Greek-Byzantine. During the era of iconoclasm, Christians in southern Russia maintained relations not with iconoclastic Byzantium, but with Iberia (Georgia) and, via Asia Minor, with Palestine. Despite the unusualness of this route for that era, it seems it had long been familiar and well known. It is possible that the southern Russian Christians recalled their earliest connections with the primitive Christian lands—connections which had been forgotten in the 7th and 8th centuries. Apostolic preaching undoubtedly reached the North Caucasus and from there, naturally, could have spread further to the Don.

With the time of St. Vladimir, Christianity did not begin in our land, but rather, its most ancient period had already ended in Rus’. This was marked by the adoption from Byzantium of liturgical rites and the church-canonical structure of life. This ritual, purely external and state arrangement of the church was not the soil or the fundamental spreading of the faith itself and of universal Christian concepts. For centuries before this, the faith had already been active and developing here, not only quantitatively but also qualitatively, cultivating in people refined Christian moral concepts. In accepting from the Greeks the external and state structure of the already long-existing church, the Russians did not adopt from them any of the Christian moral concepts relating to personal and social life. These concepts had been known to our ancestors even before the official triumph of Christianity in Russia; in this respect, our forebears were thoroughly independent of the Greeks—even stood above them: Greeks, in the eyes of Russians, were always seen as cunning people. Such a view could not have arisen if, in the time of Vladimir, Russians stood below the Greeks in moral and genuinely religious terms.

In Russia, as at the apex of a cone, converged the threads of many local Christian churches. From Byzantium came liturgical practice and church-canonical order. Bypassing Byzantium, through the Caucasus mountains, came religious thought from the more ancient churches of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria—a thought rich in Eastern creativity and deep critical spirit.

Despite the continual unity of the Byzantine and Alexandrian churches, there was a profound human difference between them. From its very founding, from the time of Constantine the Great, Byzantium distinguished itself from all other churches by its external ecclesiastical construction, the creation of liturgical order, and so forth. Emperors honored patriarchs with splendid sakkos vestments; Justinian built the church of Hagia Sophia. All other religious creativity of Byzantines, of the entire people, followed in the same direction. By contrast, in Alexandria, the principal concern was church teaching, the elevation of the human spirit in evangelical truth, and the construction of all human relations—social and civil—on this truth. The traces of this are clearly visible in the works of the writers of the Alexandrian church from Origen to Cyril, that is, over two centuries. Instead of the temporary and local church building projects that captivated the Byzantines, the Alexandrians sought to solve universal, global, and eternal questions—concerning the all-encompassing power of Christianity, sanctifying all aspects of human activity, transforming the very essence of human life, and restructuring law and the state on new principles, not on conditional and arbitrary ones as with Roman law and government, and as with all law and governments up to now, but on eternal human principles. Universal Christian thought found its fullest and deepest expression in Alexandria, more so than anywhere else. For many centuries, the Alexandrian fathers and writers were true universal teachers, examples even for such great fathers as Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom. The Alexandrians did not succeed in bringing their great designs for the reordering of the whole world to fruition: they were equally hindered by Rome, with its conditional law and striving for hierarchical infallibility, and Byzantium, with its external and incidental church construction. Yet the very posing of these questions and the very existence of these intentions must be credited as a great merit to the Alexandrian church.

Traces of ancient Alexandrian thought are evident in Russian consciousness from the time of Vladimir. In our Slavonic tales, the moral aspect is always foremost, and the same is true in our commentaries on Holy Scripture; to this day, in books of interpretation, the sections most beloved by Russians are those labeled “vozvodnoye,” that is, the moral explanation of a purely historical event. Alongside the official development of church life and the consolidation of state hierarchy, there was always another religious life flowing within the people themselves—a moral elevation of the human person, the subjection of all things to the judgment of God, and the transformation of state and ecclesiastical authority into a moral duty. Our elites, in their ecclesiastical and governmental construction, wished to imitate the Greeks with all their liturgical and social rituals, right down to the episcopal sakkos and the royal gates. The people did not resist this upper current, but neither did they regard it as the very essence of religious life; they looked deeper and instinctively, and consciously, strove toward universal and all-encompassing moral goals and ideals. It is possible that this striving is an inheritance from ancient Alexandria, which reached us bypassing Byzantium and even before the official adoption of Christianity.

Let us point to just two tales that clearly express the all-human aspiration of the Russians.

In the Menaion of St. Macarius is found the following tale. St. Pamva (an Egyptian ascetic who lived in the famous Nitrian desert in the fourth century, commemorated on July 18th) had a disciple. The disciple once asked for permission to go to Alexandria to sell some handicrafts. He spent a whole week in the city and, when he returned, St. Pamva questioned him about what he had seen in great Alexandria, what he had heard and done. The disciple recounted how he had seen the patriarch and received his blessing, how he had spent seven days and nights in the porch of the cathedral of St. Mark the Apostle, enjoying the marvelous singing of the stikhira and canons and the solemn patriarchal services. Bitterly, the disciple complained that in their desert they had no leather-bound books, heard no chanting of stikhira and canons, and saw no episcopal services. The holy ascetic replied: “Wait, all this will come to us as well: there will be leather-bound books, the desert will resound with loud singing and wonderful episcopal services. Bishops will settle in the deserts and ride about on splendid white horses, surrounded by hosts of priests and singers. And then a great abomination will strike the whole land: bishops will become lovers of silver, greedy, gluttonous, deceitful, cunning, cruel, bloodthirsty, and man-hating.” “How then can one be saved?” asked the disciple. “Let each, in saving, save his own soul,” answered St. Pamva.

In the book “The Passion of Christ,” in its first printed edition at the end of the seventeenth century, a true rarity, there is the following account, omitted from all later editions. At the descent of our Lord Jesus Christ into Hades, an innumerable multitude of high priests, kings, princes, hierarchs, grandees, boyars, military leaders, priests, and all sorts of church and civil ranks gathered at the gates of hell. At the preaching of John the Baptist, all this nobility pressed from the near and far dungeons of hell to the very gates and arranged themselves according to their rank, hoping to greet Christ on behalf of all common humanity, expecting that He would deliver them before all other people. Upon hearing of the Savior’s coming, the powers of hell gave way, and among the countless millions a remarkable commotion arose. For Christ’s arrival, people themselves established some order: the first places were taken by the high priests and kings, and so on, while the common folk were left to jostle in disorder at the back. Entering Hades, the Lord cast a stern and sorrowful gaze upon the countless ranks of high priests, kings, and all the great ones—former rulers of earth and shepherds of souls who had deceitfully governed with the word of God. All fell prostrate, and as the fearful, trembling ranks parted, the Lord silently passed into the further chambers of Hades. There were gathered all the humble and destitute of the earth, those wounded by life, embittered murderers, hungry robbers, fornicators, harlots, and so on. “Your sins are forgiven you,” said the Lord to them, “you have greatly suffered on earth because of the rulers and authorities, you did not keep My commandments and did not know love among yourselves. Come, follow Me.” And Christ led them all out of hell, passing by the countless ranks of high priests, kings, and grandees, paying no heed to them. And they all cried out to the Lord, beseeching Him: “Did not we, Lord, serve Thee? Was it not in Thy name that we ruled on earth? Did we not teach Thy law to the people subject to us? And as for those whom Thou takest with Thee—what good did they ever do Thee? Were they not a disgrace to us and to Thee on earth?” “I know,” the Lord replied to them, “you knew My commandments and strove to break them. From you the earth groaned, soaked in human blood and covered in crimes. My heart turns away from you. Depart from Me!”

Let these tales be factually untrue, but undoubtedly the voice of ancient days and profound, universal human thought resounds in them. The same idea is instilled in both; only the outward design differs. Both serve as the foundation upon which church and civil laws should be established—not random and temporary, but universal and eternal.

True church development, true church life, is not expressed wholly in the external, physical realm, perceivable and observable by the senses; it is the domain of the inner transformation of the human being, not of outward service to God, but of inward likeness to Him. Theological thought is lofty, knowledge of Holy Scripture is precious, but of itself, without inner renewal, all this is nothing more than a leather-bound book, which will be consumed and decay, which one may constantly hold in one’s hands and know entirely by heart, and yet be deeply hateful to God, a blood-drinker and a man-hater. Beautiful and moving is the singing of stikhira and canons, but this is only outward artistic beauty and may not be accompanied by inner elevation. Great is the episcopal and royal ministry, but in the episcopal office one can be a servant of Satan, the murderer of men, and not of Christ, Who is love; and with the royal scepter in hand, it is easy to become a fomenter of disturbances, disorder, and cruel crimes. Knowledge of Holy Scripture, the outward beauty of Christian worship, and the very episcopal authority may not be expressions of true church life; they may lose their original significance and become merely visible varnish on a tomb with a rotting corpse inside.

From the time of St. Vladimir, when state authority became Christian, it firmly and unswervingly followed Greek church models. Churches were built, monasteries established at the courts of princes and boyars, church art and architecture, icon painting, chanting, and splendid processions with crosses were introduced; bishops, headed by the metropolitan, were brought into the highest governmental circles and acquired a defined and very lofty state standing. In short, in our land everything that existed in Byzantium was repeated according to a ready-made plan—repeated on a smaller scale and with less artistic finish in detail. Alongside this purely external church construction, both artistic and legal, another movement developed more vitally and powerfully. Mercy and Christian love, rather than external law, were placed first in all human relations. Not lordship, but a sense of one’s own unworthiness before God and men was regarded as the highest dignity of a person. Lacking external education and being mostly illiterate, our people were nonetheless astonishingly mature in moral thought, alive in spirit, and possessed a truly poetic fervor, with which vast numbers of Russians, sparing no effort and even at risk to life, strove for all that was best and holiest in the broadest sense of these words.

Not pride or self-consciousness of one’s worth, but the awareness of one’s unworthiness did the Russian place as the foundation of the moral personality. From this awareness, he derived the whole circle of his political and social rights, as well as the entire sphere of lofty moral demands and concepts. A vivid illustration of this is the testament of Vladimir Monomakh to his children: “Receive with love the blessing of spiritual men… Have no pride either in mind or in heart, and think: we are but dust, alive today, tomorrow in the grave… On the road, on horseback, if you have no task, instead of idle thoughts recite prayers by heart, or repeat at least a short but better prayer: ‘Lord, have mercy.’ Never fall asleep without a prostration; and if you feel unwell, make three prostrations to the ground. Let not the sun find you in bed. Go early to church to offer up the morning praise to God; so did my father, so did all good people. When the sun shone upon them, they glorified the Lord with joy.” In these words is reflected a profound philosophical worldview. Even with a princely crown upon his head, a man must first and foremost consider his own nothingness; his affairs of state he must, as with beads, intersperse with words of prayer; he must begin and end the day with gratitude to the Lord. Political and social rights, all of daily human life, here are colored by deep faith, in its pure and perfect form, without any scholastic or logically-dogmatic forms. Theologically subtle and logically difficult concepts of two wills, of the meaning of hypostasis, and the like—upon which Byzantium’s religious life was built and sustained—perhaps never even entered into Russian religious consciousness; at any rate, the whole circle of Byzantine dogmatic thinking, though remaining a cherished ancestral tradition, had no vital practical significance on Russian soil. Faithful thought found here for itself an entirely new and, from a universal human point of view, a more important and interesting path.

A. S. Khomyakov, for all his respect for Byzantium, justly reproached it for retaining pagan elements, though under Christian names. It divided man into two: into the Christian ascetic, indifferent to all external life, and the suffering Christian, submitting to the random laws of the state. Civil law remained independent of faith. The emperors, in defiance of Christianity, called themselves divine (divus) and styled themselves “our eternity” (perenuitas nostra). Laws concerning marriage, slaves, property, and the like retained the indelible imprint of pagan indifference to the principles of morality. The Church, recognizing itself as perfect, neither extended nor sought to extend itself to the eternally imperfect structure of society, allowing it to claim the ambiguous right to call itself Christian based on the confession of its members; nor did it nurture in the Christian soul a moral aspiration for harmony between his civic and human duties; it inspired no hope for a better future, nor reminded him of the great truth that the external form must sooner or later become the expression of the inner content, and that law must ultimately rest not on conditional and arbitrary, but on eternal and human foundations.

In contrast to this Byzantine reality, and the dominance of pagan principles within it, in ancient Russian society, at the very root of the national consciousness, lay a profound moral principle—essentially Christian and human. The citizen was absorbed into the Christian, and the Christian moral principle became the foundation of law and authority. The proud mind of the Greco-Roman easily and quickly adopted the view of Christ as the source of all power and state authority. In substance, Christianity itself, in its pure apostolic form, gained nothing by this; there was only a substitution of the name Jupiter-Zeus for the name Christ the God-Man—more precisely, the pagan Jupiter-Zeus assumed the name of Christ. Just as previously to Jupiter-Zeus, so now to Christ did men look as the dispenser of royal scepters and high-priestly staffs. The suffering Christ, healing the sick, sharing meals with public sinners, forgiving robbers, making His first disciples out of those considered the dregs of society—in short, Christ living and always abiding among people, and especially among the humiliated and insulted—did not find faith in Himself, either in Western Europe or in Orthodox Byzantium. The Russian person, however, first of all believed in the suffering Christ, the Helper of all who were wronged, overlooked, poor, and unfortunate. Vladimir Monomakh did not think that his princely power originated from Christ and rested upon Him; he believed that at every important affair, one must sincerely and humbly say, “Lord, have mercy,” that one must begin and end the day with a prostration before God, and that every human title is perishable and insignificant. The son of Monomakh, Grand Prince Mstislav, as the Prologue states, “did not take silver or gold into his hands, for he did not love riches.” These views and examples were not unique; they fill all the oldest Russian chronicles and all the accounts of saints composed on Russian soil and widespread among Russians. These views formed the soil in which Russian religious thought was born and grew. The chronicler Nestor wrote of monasteries: “Many monasteries are founded by kings and nobles and from wealth, but they are not like those founded with tears, fasting, prayers, and vigils.” Power and wealth cannot be means for the flourishing of faith; for that, there is only one means—personal and communal consciousness in the Christian spirit.

With these Russian views, law in its very foundation acquires an entirely new meaning, a different sense and content, and all social relations are changed at their very root. These views are utterly incompatible with the organization of society on Roman-Byzantine and modern principles, and sharply underline the pagan character of many ideas still considered fundamental to Christianity. Above all, they are incompatible with the notion of Christ as the source or founder of all earthly, and also ecclesiastical, authority. Dominion, especially in the name of Christ, slavery, and the division of people into classes, are utterly rejected and shown as anti-Christian principles. The church community can only be self-governing, fostering the freedom of each individual member. Pastorship does not lead to any outwardly honored position, but can only be the expression of inner Christian humility and of inward Christian love. Yet, none of these principles was destined to develop openly and acquire state significance. Byzantine principles—essentially pagan, though merely cloaked in Christ’s name—gained decisive dominance and entered into the very flesh and blood of state and externally ecclesiastical construction.

Not having gained predominance above, the truly Christian principles built for themselves a very strong and extensive nest below, among the very heart of the people. Gradually, the people remained alone, as if without rulers and representatives, and continued to be nourished solely by moral principles—by concepts of Christian love and humility. In Russian tales, little space is devoted to the triumphant Christ, building kingdoms and thrones, to the church victorious and adorned with gold and silver, to hierarchs crowning kings and appearing in all the splendor of earthly greatness. But there are very many tales of another sort: about Christ as a poor boy leading the blind and collecting alms with them from the poorest and most miserable people; about a church in a humble cave, with extraordinarily poor furnishings and impoverished worshipers, among whom is found a shiningly holy but unknown holy fool; about hierarchs and bishops traveling with a simple staff, in worn clothes, and in the company of the most ordinary people. St. Nicholas takes the sword from the executioner and saves the unjustly condemned. St. Sergius feeds the bear, serves in a threadbare robe with a wooden chalice, and is vouchsafed a miraculous visitation from the God-bearer. In all these tales, deeply human principles shine forth brightly, and there is no aristocracy, no hints at rights and privileges in the usual sense of those words, no sign of one ruling over another.

Under the influence of such moral forces, the simple Russian people developed a special understanding of law in general, and of church law in particular—an understanding that has nothing in common with Greco-Roman ideas, and testifies to a new, deeply human culture, a new sense and content of faith, a new social order and way of life.

For centuries, Christian-human concepts among the people did not diverge from Byzantine notions above, in the ruling classes. Among the higher ranks there constantly appeared individuals ablaze with living popular faith and hopes. Their inner holiness and purity reconciled the people to the purely Byzantine position which, reluctantly and by necessity, they held. This reconciliation was incidental and forced. The closer time drew to Nikon and Peter I, the more clearly this reconciliation of two fundamentally different principles began to be disturbed, and in the time of Nikon it was finally shattered.

The essence of Old Belief is to be sought not in ritual, nor in the replacement of one rite with another, but in the very meaning of the faith of the people, on the one hand, and the Byzantine-state position of the hierarchy, on the other. In this sense, Old Belief is the lawful heir of the most ancient Alexandrian Church, and is called to renew and further develop the Christian and universal human thought of that Church.

V. Senatov

“Church,” 1909, No. 1

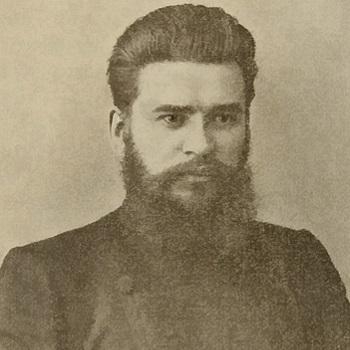

A public figure and prominent leader of the Old Believer movement at the beginning of the 20th century, Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was a Russian photographer, documentarian, artist, and owner of a photography studio. He also distinguished himself as a reporter, writer, journalist, publicist, and apologist for Old Belief. The multifaceted nature of N.D. Zenin’s personality was expressed not only in his fluency with theological issues and passionate confession of his faith. Along with like-minded allies and companions, he devoted his life to the struggle for a better lot for the Old Believer community — for freedom of religion, conscience, and the individual; for the purity of the Orthodox faith; and for the cultivation of a cultural environment for Old Believers. Nikifor Zenin was also a book publisher and organizer of libraries. He was elected to the city council (Duma) of the Moscow-region town of Yegoryevsk and served as an elector to the State Duma. He was engaged in charitable work and was a member of the Society for Aid to the Poor, a member of the Yegoryevsk Volunteer Fire Society, and a member of the Voskresensk Volunteer Fire Brigade.

Origins: The Zenin Family and Nikifor

Nikifor Dmitrievich Zenin was born in 1869 in the village of Gostilovo, Chaplyzhensky volost, Bronnitsky uyezd, Moscow Governorate (now Voskresensky district, Moscow region), into a peasant, patriarchal Old Believer family. His ancestors, the Zenins, had lived in Gostilovo “from time immemorial,” at least since the earliest written references to the local inhabitants, preserved in cadastral and census records from the 17th century. During the reign of Peter I lived a man named Zenovey (diminutive: Zenya), and his descendants came to be called Zenin. Zenovey distinguished himself in some way, and his name was remembered for a century and a half — up until the abolition of serfdom, when surnames were officially assigned.

According to family tradition, “the Zenin peasants were never serfs.” This tradition is only partially true. For many generations, the Zenins had in fact been serfs under the noble family of the Kustersky. The relationship between the Zenin peasants and their landlords was complex. For reasons unknown, in 1836, eight men of the Zenin family of various ages were granted freedom all at once — including Nikifor Dmitrievich’s uncle, Vasily Ivanovich. By the time Nikifor Dmitrievich was born, the Zenin family was the strongest in Gostilovo. Nearly all the Zenins were literate. The foundation of their prosperity was unceasing labor and avoidance of wasteful and corrupting vices.

Nikifor’s father — the peasant Dmitry Ivanovich Zenin (Oct. 30, 1825 – Nov. 8, 1909) — can rightfully be counted among those whose efforts sustained and developed the nation. He was a great laborer and a capable steward. In addition to their native farming, the Zenins grew apples and engaged in “paper and weaving work.” Beginning in 1853, Nikifor’s father, though still a serf, owned a home-based “paper-weaving factory” with a total of 60 looms and an annual turnover of 7,500 rubles. They wove 1,500 pieces of nankeen cloth per year. The Zenins owned two houses, four horses, two cows, small livestock, and the largest area of leased land in the area. They also ran a shop where they sold manufactured and other goods.

Nikifor was the youngest son. Before him were born four brothers — Ivan (Ioann), Xenophon, Kondraty, and Barnabas — and a sister, Aksinya. In February 1881, Nikifor’s brother Xenophon died; in April of the same year, his brother Ioann died at the age of 31; and on June 16, 1905, another brother, Kondraty Dmitrievich Zenin, tragically passed away at the age of 45. Nikifor had great respect for his father, as evidenced by the inscription on the preserved gravestone:

“Peace to your ashes, great laborer. To you, before the greatness of whose spirit I always bowed, with this monument I fulfill my final duty. Now it is my turn. Your son, Nikifor. Yegoryevsk, October 11, 1915.”

Officially, the Zenins were listed as peasants, but in practice, their family had already begun to rise into the higher social classes of the Russian Empire. It is no coincidence that in the memory of the local old-timers, the Zenins were remembered as merchants. The upbringing of the children was overseen by their mother, Agafya Gavrilovna (1830–1907), “a true Christian.” She taught her son to be truthful, straightforward, and entirely candid. Nikifor Dmitrievich received a good education. He knew several languages: German, French, Polish, Latvian, Esperanto, and all Slavic dialects. He was married to Maria Vladimirovna, a peasant from the village of Gostilovo. The Zenin family, like most residents of Gostilovo, adhered to the Old Christian Orthodox Faith (Old Belief).

Military Service and Arrival in Voskresensk. First Photographs

At age 21, Nikifor Dmitrievich was drafted into the army. He served in the headquarters of the Sixth Infantry Division. As a soldier, Nikifor Zenin served exemplarily and earned promotion to the rank of non-commissioned officer (feldfebel) and to a class-rated position.

“As a son of my motherland, I personally served both the Sovereign and the Fatherland, served honestly, zealously, as duty demands. For my service in His Majesty’s troops, I received promotions, commendations, and monetary rewards,” he wrote in a 1910 petition to the governor of Ryazan. Upon discharge, he was “publicly told that if all soldiers in the Russian army were like him, the Russian army would be on an unassailable height.”

In 1894, after his discharge from the military, Nikifor Dmitrievich moved to live with his nephew Nazar in the settlement of Voskresensk. By that time, Nikifor Zenin had already mastered the profession of photography. Near the Voskresenskaya station (as he labeled it on his photographs), he established his first photography studio and took his first photographs.

Move to Yegoryevsk. Opening of the Studio

In 1895, Nikifor Dmitrievich moved to Yegoryevsk. He later recalled:

“I was still a very young man when fate cast me into Yegoryevsk. Raised in a village amid the pure, holy nature unspoiled by the foul breath of modern ‘culture,’ and by a mother who was a true Christian, I did not know real life in its present form. At that time, I thought that it was enough to proclaim goodness and truth to the world, and the whole world would recognize them and bow before them…”

Nikifor Dmitrievich and his wife, Maria Vladimirovna, lived in the Sharapova heirs’ house (as of 1910) on Moscow Street. The fate of their son Mikhail (born 1899) is unknown. It is known that Nikifor’s older brother Barnabas Dmitrievich also lived in Yegoryevsk with his son Alexei. By this time, Nikifor Dmitrievich was already working as a photographer. His earliest known photographs are dated 1898. Over time, N.D. Zenin refined his craft, gained recognition as an artist, and opened the “Workshop of Light-Painting” (Masterskaya svetopisi).

In addition to all sorts of purely photographic work, the Workshop of Light-Painting also produced in small batches and at “very low prices” the following: Visiting-card portraits, Cabinet portraits, and postcards (open letters) with portraits and scenic views. The studio also offered enlargement and retouching of portraits. All these services were performed either from the studio’s own negatives (which were kept in their archives) or from photos and negatives sent in by customers.

Later, he opened another photography studio called “Progress.”

N.D. Zenin became an official member of the Russian Photographic Society in Moscow. Gradually, people began to gravitate toward the young photographer. Portrait cards produced by Nikifor Zenin could be found in almost every household in Yegoryevsk. He left to posterity numerous photographic records of Old Believer life from that era. It was he who photographed many representatives of the Old Believer clergy and church-community figures. Thanks to his efforts, a photographic gallery of Old Believer figures from the Belokrinitsa Concord was created.

Nikifor Dmitrievich not only took portraits of contemporary priests and bishops himself, but also sought out photographs of those he did not know personally. By reproducing both types, he helped preserve the iconography of the Belokrinitsa hierarchy. Zenin’s photo archive was included in the Photo Chronicle of Russia project.

In addition to photography, Nikifor Dmitrievich had another profitable venture: publishing and bookselling. He printed his books only in Old Believer printing houses, since he did not have one of his own. In Yegoryevsk, he owned a book warehouse and shop, as well as a large library. Nikifor Dmitrievich was a highly enterprising man: in addition to various books, he published luxurious photo albums, series of postcards featuring views of Yegoryevsk, and sold various related goods — all of which enabled him to remain financially independent.

Beginning of Public and Ecclesiastical Activity