Byzantine Traditions in Old Russian Art #

By Roman Atorin

Modern sociocultural transformations in Russia have led to a growing interest in Orthodox culture as a whole, and in ecclesiastical art in particular. Orthodoxy serves as a conduit of Old Russian culture and art, a bearer of traditions, and a source of spiritual and historical values. Today, the study of the development of church art is a vital component of Russian culture. As a structural element of national culture, ecclesiastical art contributes to the transmission of sociocultural principles, values, and norms.

At the dawn of the third millennium, as Russia is called to spiritual renewal, it is highly significant for individuals to recognize that the Orthodox faith—brought to Rus’ from Byzantium—has become the foundation of their worldview and culture. This fact explains the renewed interest in Byzantine theological concepts and their influence on the spiritual life of ancient Rus'.

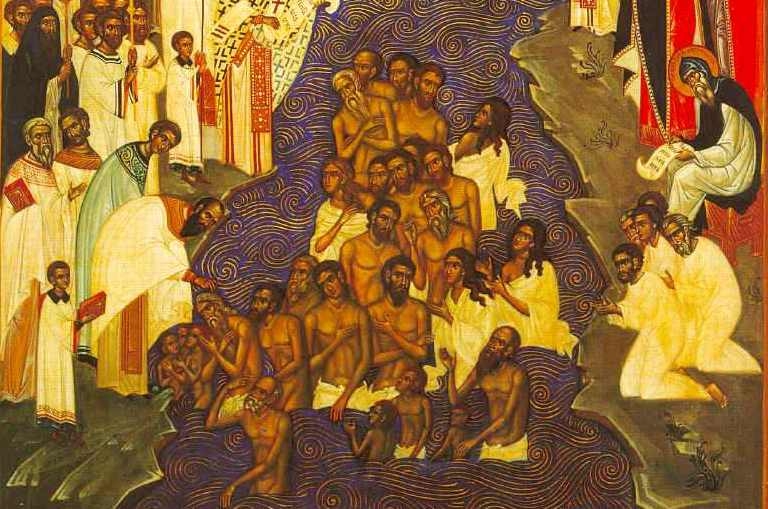

The interaction between the artistic traditions of ancient Rus’ and Byzantium is evident and has long been a subject of study in various fields such as art history, cultural studies, philosophy, and more. A vivid example of this interaction is religious painting, embodied in the works of outstanding artists who followed the Byzantine tradition of hesychasm.

Interpreting the artistic legacy of Old Russian iconographers—Andrei Rublev, Theophanes the Greek, and Dionysius—through the lens of Byzantine ideas and traditions is of great interest to contemporary scholarship. Thus, the topic “Forms of Artistic Ties with Byzantium and the Specifics of the Reception of Byzantine Traditions in Rus’” remains timely and important.

The issue of artistic ties between ancient Rus’ and Byzantium, along with the major aspects of Byzantine influence on Old Russian art, continues to attract the attention of numerous researchers.

This topic has been addressed in the works of such authors as S. S. Averintsev, V. V. Bychkov, G. I. Vzdornov, M. N. Gromov, I. Gulyayeva, I. I. Evlampiev, D. S. Likhachyov, L. D. Lyubimov, V. A. Plugín, N. V. Pokrovsky, T. A. Subbotina, F. I. Uspensky, P. A. Florensky, I. K. Yazykova, and others.

A deep internal unity connects the Byzantine spiritual-artistic tradition with Old Russian iconography. The aesthetics and theology of the icon are rooted in the ideas of the Byzantine Church Fathers. The Russian icon is genetically tied to the theological and philosophical ideas and principles of Byzantium.

Ancient Rus’ adopted Orthodoxy at the end of the 10th century, and in doing so encountered a highly complex cultural challenge. The matter lies in the fact that Rus’ was pagan—not simply pagan, but lacking any culturally developed expressions of that paganism. No evidence has been found of a written religious tradition, nor of a developed ritual system, nor of public worship with temples. In adopting Orthodoxy, Rus’ faced the formidable task of embracing the Byzantine tradition—a tradition unique within European culture, one which had assimilated many cultural and religious currents, including both classical antiquity and Christianity, as well as their wondrous synthesis. To transmit such a vast legacy not merely to an elite stratum but to the many tribes just beginning to coalesce into a people, Byzantium could rely only on its churches.

What, then, did the Orthodox church building signify in a cultural sense? What role did it play in shaping the worldview of the Russian person? It is well known that all Russian writers passed through the formative influence of the Church1.

The Baptism of Rus’ became a breakthrough for us into the great world culture. For the greater part of its history, Christian humanity remained within the framework of ecclesiastical culture, until the divisions within the Orthodox world under Patriarch Nikon.

With the adoption of Christianity, Ancient Rus’ inherited from Byzantine civilization the legacy of “the cultivation of the inner man,” a teaching founded on beauty understood as goodness, truth, and love. The icon became the visible embodiment of the invisible, suprasensory world. The canon of iconography was initially adopted from Byzantium. An icon created according to the canon was a visible representation of the correct understanding of the Christian faith, a spiritual guide both in the world and within the human soul. “The place of the icon in Russian medieval culture is defined by a distinctive ‘crossroads’ between the vertical line of the metaphysical highway ‘man–God’ and ‘God–man,’ and the horizontal paths of the religious-philosophical exchanges between Byzantium and Russia. These contacts determined the systems of inviolable principles in grasping the spiritual heritage”2.

Through the work of Greek artists, theological and artistic styles spread throughout Rus’. By the 11th century, we see the activity of the first known Russian iconographers—disciples of the Greek visitors—such as St. Alipy and St. Grigory.

It is known that in 1385, a translation was made of a book by the 12th-century Byzantine author George of Pisidia. The “Letter of Epiphanius to His Friend Cyril,” dated to 1413, is a work directly related to visual art. A major expression of the guiding principles that developed in icon painting up to the end of the 15th century is found in Joseph of Volokolamsk’s “Letter to an Iconographer.”

The forms of Old Russian religious art were based on the cosmological, anthropological, and eschatological views of Byzantine theologians. Byzantine-Russian icons depicting Holy Wisdom (Sophia) embodied Divine Wisdom. It is important to emphasize that Byzantine philosophical and religious traditions had a profound impact on the formation of Old Russian iconography. A particular influence on the development of Old Russian ecclesiastical art was exerted by the system of hesychasm.

Hesychasm, as a mystical-ascetic tradition within Orthodoxy, is a classic example of a highly organized and refined mystical experience. Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev notes that Orthodox asceticism, in its practical aspect, is directed toward “the liberation of the human personality”3. The ascetic experience is one of raising the entire human being “up the ladder” toward God, accomplished by grace through prayerful communion with God. The reception of hesychasm played a major role in the flourishing of Russian iconography in the 14th century.

Hesychasm serves as a key to understanding the deepest meaning of Christian morality and Orthodox spirituality in the spirit of the patristic tradition. The hesychast strives to experience the gift bestowed upon him by the incarnate Son of God. He does not seek to claim God’s grace by extraordinary merit—for it is freely given—but rather to preserve himself upon the heights of his calling, to attain personal experience and mystical knowledge of Christ’s triumph over the power of the Evil One, of corruption and death, and to remain in the realm of freedom in Christ.

For Ancient Rus’, due to the particular character of its national religiosity, iconography became the closest means of expressing the ideas of hesychasm, dogmatic teaching, and moral-theological creativity. In Old Russian iconography, the central themes of hesychasm were clearly reflected: the Supreme Good, virtue, the relationship between good and evil (virtue and sin), and the ethical interpretation of the themes of the Transfiguration and the Last Judgment. Icon painting was directly tied to the spirit of hesychasm; the very structure of hesychastic dogmatics is founded on the continuity of the dogmas of icon veneration. Iconography is the beginning of divine vision (theōria), which is realized in the mysticism of hesychasm. The icon serves as a means both of expressing hesychastic experience and of drawing others into it.

As M. N. Gromov notes, “Among the causes that influenced the formation of the high Old Russian iconostasis, there is undoubtedly the impact of hesychasm… Hesychasm gave the creative impulse, while older local traditions of woodwork made it possible to create something new, something unique, which did not exist in Byzantium”4.

Spiritual and hesychastic motifs are especially prominent in Old Russian painting. The great painters of Old Rus’ drew their inspiration from that light which faith in God and in Christ gave them. The Gospel scenes portrayed in painting are weighty proof of the high moral value of the Bible. In iconography, hesychastic ideas were embodied by such renowned Old Russian iconographers as Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev, and Dionysius.

Theophanes the Greek, who came to Rus’ at the end of the 14th century, stands among the most distinguished iconographers of the Russian hesychastic era. He brought to Russian soil the highest achievements of Byzantine cultural tradition. Theophanes created images filled with divine joy, perceived through spiritual and mystical revelation. A. V. Yazykova writes: “Only in the context of hesychasm does the pictorial language of Theophanes become somewhat comprehensible. The master reduces the entire palette to a distinct dichotomy: he paints with only two colors—ochre and white. Upon an ochre-clay background (the color of earth), the lightning flashes of white highlights burst forth (light, fire)”5.

V. V. Bychkov remarks: “The painting of Theophanes is a philosophical concept in color—indeed, a rather austere concept, far from everyday optimism. Its essence lies in the idea of the global sinfulness of man before God…”6 T. A. Subbotina writes: “The imagery of Theophanes’ murals shows that the monochromaticity was deliberately chosen by the master as a metaphorical language. The color minimalism of this painting can be likened to the hesychasts’ renunciation of verbosity in prayer: reducing their prayer rule to a few words of the Jesus Prayer, hesychasts achieved astonishing concentration of thought and spirit. Theophanes the Greek likewise achieves such concentration in his painting”7.

This technique is especially well expressed in his depiction of the founder of monasticism, St. Macarius of Egypt (in the Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Novgorod), a 4th-century ascetic. “Theophanes vividly demonstrates to us the effect of the Taboric light upon the ascetic. It is a unique and very striking sermon on the hesychastic path, a call to follow it. The elongated, candle-like figure of the ascetic is entirely enveloped in light, like in a white flame. White highlights flash across the face of Macarius, but his eyes are not painted at all. This strange technique is a conscious choice: the saint has no need of bodily eyes, for he sees God with the inner (spiritual) gaze; he does not look upon the outer world. In the process of divine communion, the ascetic is immersed in light, in divine reality, and yet he does not dissolve into it—he retains his personhood, which seeks purification and transfiguration”8.

According to G. I. Vzdornov, “The worldview of Theophanes is dualistic, and it finds clear expression in the tragic imagery of his somber imagination. The faces and gestures of the saints in the frescoes of the Church of the Savior convey pain, fear, deprivation, sorrow, and a dark steadfastness of spirit. But there is no room here for deliverance from suffering or spiritual searching. These are living symbols of hopeless despair, and they cannot offer the beholder any consolation of soul”9.

In the icon The Dormition of the Most Holy God-bearer (last third of the 14th century), Christ is depicted within a mandorla of black color. At first glance, this evokes a sense of tragedy, but when one turns to the writings of the hesychast Fathers (Symeon the New Theologian, Gregory Palamas), it becomes clear that for them, the divine light is a supra-luminous darkness. According to early hesychastic teaching, this light is impenetrable—just as God Himself is unknowable. Regarding the black mandorla in which Christ is depicted wearing golden garments, S. S. Averintsev writes: “Gold, the emblem of moral integrity—that is, of chastity—is also the emblem of bodily flesh. Gold is the emblem of incorruption. It is not merely something bright and precious, but is associated with the idea of suffering purification and fearsome trial”10. Here is depicted the path from the black garments of monasticism, through hardship and testing, toward transfiguration—toward transformation into radiant white and golden light.

Thus, the artistic-philosophical concept of Theophanes the Greek demonstrates the influence of Byzantine hesychasm transplanted to Russian soil. His iconography reflects deep spiritual insight and the contemplative experience that characterized the Byzantine-Russian worldview of the late 14th century.

The artistic legacy of the monk of the Andronikov Monastery, Andrei Rublev, is a vivid example of a nationally distinct phenomenon imbued with universal spirit. The great master created his iconographic images “not from the somber Byzantine palette, but from the nature that surrounded him: white birches, ripening green rye, golden wheat stalks, and bright cornflowers. In the icons and frescoes of Andrei Rublev, one can observe a movement away from the Byzantine tradition and the emergence of a distinctly Russian tradition, characterized not by terror before the Last Judgment, but by hope for a transition from earthly life to a bright and eternal afterlife, and trust in the mercy of a compassionate Christ”11.

His Trinity icon is the symbol of the 14th–15th century epoch. In it is embodied the contemplative foundation of the Byzantine doctrine of hesychasm. The Trinity is a sphere of silence and peace, a revelation of submission and harmony. The artist succeeded in finding expressive means to convey theological, philosophical, and moral ideas. As D. S. Likhachyov states: “The angels, symbolizing the three Persons of the Trinity, are immersed in a sorrowful contemplation, and the one who prays enters into communion with the icon through ‘noetic’ (mental) prayer”12.

The symbolism of color is precise and expressive. Color reveals to the viewer the delicate harmony of relationships, deeply felt and carefully balanced. The radiant hues are marked by harmony and luminosity. They accord with the overall philosophical-artistic structure of the icon and are illuminated from within, inviting quiet contemplation.

The Trinity icon embodies the idea of the Trinitarian structure of the universe. One of its deepest spiritual meanings lay in fulfilling the testament of the great gatherer of Russian lands around Moscow—St. Sergius of Radonezh. The Trinity was created for the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, which held immense significance for Russia. It embodied the integral foundation upon which the process of forming the Muscovite state was built. Byzantium was losing its former power. Little time remained before the monk Philotheus would proclaim the idea: “Moscow is the Third Rome.”

It must be emphasized that the icons of Andrei Rublev possess an unparalleled depth of divine knowledge. His images are the principal guiding standard of iconographic creativity in Old Rus’. In Rublev’s works, one finds reflected the philosophical-religious aesthetic consciousness of Old Russia. His icons embody the essential spiritual meanings of the era—wisdom, compassion, and beauty.

The ecclesiastical art of Muscovite Rus’ in the second half of the 15th century is marked by the leading role of the “Rublevian” school. The most distinguished representative of this period was Dionysius, the greatest Old Russian painter after Andrei Rublev. In his work, Dionysius followed the artistic techniques and the aesthetic-philosophical worldview of Rublev. “The compositions of his works were distinguished by solemn rigor, the colors were bright, the proportions of the figures elegantly elongated, the heads, hands, and feet of the saints were miniature, and the faces invariably beautiful”13.

In its understanding of beauty, Old Russian aesthetic consciousness placed spiritual beauty above all. It was precisely the ideas of hesychasm, sobornost (conciliarity), and sophiology that largely defined the iconography of Dionysius.

As scholars note, “his images are filled with luminous energy. But this luminosity is not so much caused by the presence of some external, uncreated light, as it is inherent to the very world in which Dionysius’ figures live and act. The very fabric of this world is permeated with light. And the force that draws the viewer to this world is not so much spiritual as it is artistic”14.

Dionysius’ iconography conveyed a bright and joyful spirit, marked by purity and gentleness of color, with a predominance of green, gold, and white tones. Within his work developed a unique sophiological theme—religious thought has always been stirred by the question of Sophia. Dionysius was a hesychast by tradition. The ideas of hesychasm, conciliarity, and sophiology shaped the unity of his creative vision.

It must be emphasized once again that the Byzantine spiritual-artistic tradition and Old Russian iconography are bound by a deep internal unity. The art of Old Russian icon painting is genetically rooted in the cultural tradition of Byzantium. At the core of icon aesthetics and theology lie the ideas of the Byzantine Fathers of the Church. The Russian icon is directly connected to the theological and philosophical principles of Byzantium. With the adoption of Christianity, Ancient Rus’ inherited from Byzantine civilization the legacy of “cultivating the inner man,” at the heart of which is beauty—understood as goodness, truth, and salvation. An icon created according to the canon was a visible embodiment of the correct perception of Christian doctrine, a spiritual guide both in the world and within the soul of man.

In the 14th–16th centuries, Moscow became the center of the unification of the Russian lands. The Muscovite principality transformed into a powerful state, the stronghold of Russian Orthodoxy. During this period, Moscow was proclaimed the “Third Rome.” The ideological formula of Moscow as the Third Rome had a theological meaning: the mission of the Russian state was to preserve true Christianity in its Orthodox form.

“Moscow—the Third Rome” became a theory with cosmological, historical, eschatological, and messianic justification. If the Third Rome is understood as the final earthly kingdom, then Moscow concludes human history and heralds the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven15.

This ideologeme, formalized as the central idea of the Muscovite state, assumed the affirmation of a distinct national cultural space—something that left a profound imprint on all of Russian culture, and particularly on ecclesiastical art. Emphasis was placed on the development of a national art form.

By this time, Russian culture had already absorbed and reworked the rich Byzantine heritage. In doing so, it rejected everything alien to its national aspirations: the representational grandeur of imperial Byzantinism and the “detachment” of Byzantine artistic images. Moscow became the collector of the Russian lands because it was there that the creative force of the national spirit was most manifest—expressed in the Muscovite tradition of icon painting. The works of the Moscow school finally broke with the rigid conventions of late Byzantine tradition. In the 15th–16th centuries, Byzantine models were replaced by distinctly native aesthetic values, reflected in the great freedom of the iconographic canon and the warmth of iconographic images.

In the 15th–16th centuries, the ecclesiastical art of Old Rus’ acquired its own independent, localized features. It began to reflect key events in Russian history and was shaped by major historical processes such as the formation of a centralized Russian state. The ideological content of the art expanded, even as stricter regulation of themes and iconographic schemes also took place.

Thus, the 14th–16th century period is marked by the rise of Moscow as the center of the unification of the Russian lands and its proclamation as the “Third Rome.” Muscovite Rus’ was understood as the refuge of “true Christianity,” and this conception deeply influenced the system of ecclesiastical art and Russian culture as a whole. In the 15th–16th centuries, native aesthetic values replaced Byzantine models, finding expression in the greater freedom of iconographic forms and the warmth and humanity of iconographic images.

In conclusion, it must be noted that the theory and practice of hesychasm—particularly deep prayer (noetic labor) and contemplation of the Taboric Light—had a special and decisive influence on the development of Old Russian ecclesiastical art. In the 14th century, within the framework of the hesychastic tradition, Byzantium developed a metaphysical concept of divine light. Light became one of the principal categories in the theology of the icon. For Old Rus’, due to the unique character of its national religiosity, iconography became the most accessible and expressive medium for conveying the ideas of hesychasm, dogmatic teaching, and theological-moral reflection. All the key themes of hesychasm found expression in Old Russian icon painting. Indeed, Old Russian iconography is intimately bound to the spirit of hesychasm—even within the very structure of its dogmatics.

Within the artistic language of Old Russian iconography, two elements in particular reveal the influence of hesychasm: the symbolic use of color and the geometry of the icon.

Sources #

- Averintsev, S. S. Gold in the Symbolic System of Early Byzantine Culture // Byzantium. The South Slavs and Ancient Rus’. Western Europe. — Moscow: Nauka, 1973.\

- Berdyaev, N. A. The Philosophy of the Free Spirit. — Moscow, 1994.\

- Bychkov, V. V. 2000 Years of Christian Culture. Subspecie Aesthetica, in 2 vols. — Moscow–St. Petersburg: Universitetskaya Kniga, 1999.\

- Vzdornov, G. I. The Frescoes of Theophanes the Greek in the Church of the Transfiguration in Novgorod. — Moscow, 1976.\

- Gromov, M. N. Hesychasm in East Slavic Culture // Bulletin of Slavic Cultures. — Moscow, 2009.\

- Kolesnik, V. N. The Russian Icon as a Spiritual Model of the Orthodox Cultural Cosmos: Dissertation for the Degree of Candidate of Philosophical Sciences (09.00.13). — Belgorod, 2002.\

- Likhachyov, D. S. The Human Being in the Literature of Ancient Rus’. — Moscow: Nauka, 1970.

8 .Subbotina, T. A. The Reflection of Hesychastic Ideas in the Work of Theophanes the Greek. — Moscow, 2011.

9 .Uspensky, F. I. History of the Byzantine Empire in the 11th–15th Centuries. The Eastern Question. — Moscow: Mysl’, 1997.\ - Yazykova, A. V. The Theology of the Icon. — Moscow, 1995.

Footnotes #

-

Berdyaev, N. A. The Philosophy of the Free Spirit. — Moscow, 1994. p. 132.\ ↩︎

-

Kolesnik, V. N. The Russian Icon as a Spiritual Model of the Orthodox Cultural Cosmos: Candidate Dissertation. — Belgorod, 2002. p. 4.\ ↩︎

-

Berdyaev, N. A. The Philosophy of the Free Spirit. — Moscow, 1994. p. 57.\ ↩︎

-

Gromov, M. N. Hesychasm in East Slavic Culture // Bulletin of Slavic Cultures. — Moscow, 2009. p. 11.\ ↩︎

-

Yazykova, A. V. The Theology of the Icon. — Moscow, 1995. p. 270.\ ↩︎

-

Bychkov, V. V. 2000 Years of Christian Culture. Subspecie Aesthetica. — Moscow–St. Petersburg: Universitetskaya Kniga, 1999. Vol. 1.\ ↩︎

-

Subbotina, T. A. The Reflection of Hesychastic Ideas in the Work of Theophanes the Greek. — Moscow, 2011. p. 9.\ ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 10.\ ↩︎

-

Vzdornov, G. I. The Frescoes of Theophanes the Greek in the Church of the Transfiguration in Novgorod. — Moscow, 1976. p. 252.\ ↩︎

-

Averintsev, S. S. Gold in the Symbolic System of Early Byzantine Culture // Byzantium. The South Slavs and Ancient Rus’. Western Europe. — Moscow: Nauka, 1973. p. 50.\ ↩︎

-

Bychkov, V. V. 2000 Years of Christian Culture. Subspecie Aesthetica. — Vol. 1.\ ↩︎

-

Likhachyov, D. S. The Human Being in the Literature of Ancient Rus’. — Moscow: Nauka, 1970. p. 96.\ ↩︎

-

Uspensky, F. I. History of the Byzantine Empire in the 11th–15th Centuries. The Eastern Question. — Moscow: Mysl’, 1997.\ ↩︎

-

Yazykova, I. K. The Theology of the Icon: A Textbook. — Moscow: Publishing House of the Open Orthodox University, 1995.\ ↩︎

-

Panarin, I. N. The Doctrine of Rus’: “Moscow — The Third Rome”. http://www.panarin.com/doc/40 ↩︎