Law of God. For Young Children.

ON THE WORLD

Everything in this world has a creator. A book was written by an author, then prepared and printed in a publishing house. A pencil was made in a factory designed for pencil production. The plan of a church was designed by an architect, and then builders raised the walls — and thus the church came into being.

Much of what we see is the work of human hands: houses, cars, furniture… A person is capable of making and does indeed make many things: airplanes for moving through the sky, satellites for observing the earth from space. But there are things that a person is not capable of creating.

Take, for example, a star. No matter how educated a person might be, and no matter what material he is given to work with, he cannot make a star.

And there are many, many other things in the world that are beyond human power to create: seas, mountains, rivers. Yet all of these also have a Creator — the all-powerful and almighty God.

If we take a box of modeling clay, we can shape trees, fish, and birds from it. But we cannot breathe life into our clay tree. God, however, did not merely create the world — He gave it life. The tree made by God grows, bears fruit, and from its seed springs a new tree. And this process is repeated again and again.

Every task requires time. And God also took time to create the world. The world was created by God in six days: On the first day, God created heaven and earth and divided light from darkness. On the second day, the sky with its clouds appeared, separated from the waters that covered the earth. On the third day, God divided the waters on the earth by patches of dry land and planted vegetation. To govern the day and the night, on the fourth day the heavenly lights appeared: the sun, the moon, and the stars. On the fifth day, the seas were filled with fish, and the skies with birds. On the sixth day, God created animals and man. On the seventh day, God rested — that is, He ceased from His works.

“Six days — that’s too little,” you might say. Scientists claim that the earth was formed over thousands of years. Where is the wisdom here? When God began creating, time in our human sense did not yet exist. We are used to measuring time by the alternation of day and night. But the sun and moon were created by God only on the fourth day. The days of God’s creation cannot be measured in hours. It was some other kind of day — far longer — and so there is no contradiction between the scientific data about the earth forming over thousands of years and the spiritual understanding of the world.

A thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past.

— Psalm 89

Glory to Thee, O our God, glory to Thee, for the sake of all things.

- How is God’s creation different from man’s?

- How long did it take God to create the world?

- Can man be called a Creator?

HOLY SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION

The story of God’s creation of the world and the life of the first humans is told to us by sacred books. God Himself commanded that the key events of human history be written down, so that knowledge might be passed on from generation to generation. Thus the Bible came into being.

The word Bible comes from the Greek and means books. These books were written over the course of centuries by prophets and apostles, through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. They are called the Holy Scripture. These sacred books are more worthy than all others of our trust, attention, and study.

Holy Scripture is divided into two parts: the Old Testament and the New Testament. The Old Testament was written by the prophets and tells how faith in God was preserved on earth before the birth of Christ. By the time Christ was born, the true faith had been preserved on earth by only one nation — the Jews. The books of the Old Testament describe the history of that people and their long expectation of the Savior.

The New Testament tells of the coming into the world of the Savior, Jesus Christ — of His life and teachings, and of how knowledge of the true God spread beyond the bounds of the Jewish people and again became the possession of all mankind. The New Testament was written by Christ’s disciples — the apostles. It includes the four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and the Epistles of the holy apostles.

“Concerning many things there was also an unwritten teaching, and one must believe equally in that which is not written.”

— St. John Chrysostom

It would be impossible to contain all knowledge of God within a single collection of books. From generation to generation, knowledge was also handed down orally. Part of this was written down in the works of the holy fathers who lived after the apostles; part of it was expressed through sacred rites and established Church rules. This part of Church teaching is called Holy Tradition.

“Therefore, brethren, stand fast, and hold the traditions

which ye have been taught, whether by word (that is, orally),

or our epistle (that is, in writing).”

— Second Epistle of the Holy Apostle Paul to the Thessalonians, reading 276

- How is the word “Bible” translated?

- What are the two main parts of Holy Scripture?

- Who is the author of the Bible?

- What are the books of the Old Testament about? What is their purpose?

- What does the New Testament tell us?

GOD THE TRINITY

An Orthodox church is unimaginable without icons. They help us better envision the saints to whom we pray: the angels, the God-bearer, the saints. But on none of these icons will we find an image of God as He truly is.

No one has ever seen God. He cannot be depicted, nor described in words, nor even simply imagined. What we do know about God is that He is the Trinity. In the Trinity, there are as it were three Persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Yet despite this threeness, God cannot be divided. Existing in three Persons, He remains one God.

The holy fathers, striving to explain in some way how the Trinity can be One, offered examples. One such example is the sun. The sun is at once rays, light, and warmth. Each of these parts is always present together with the others; and only together do they make up what we call the sun. Another example of unity in three parts is a clover leaf. Each green leaf of the flower is made up, as it were, of three parts, which nonetheless remain one single leaf.

In the Old Testament, the Trinity appeared in the form of three angels to the holy forefather Abraham. The icon depicting this event is called The Old Testament Trinity.

With the coming of Jesus Christ into the world, we were given the opportunity to see the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, who took on flesh — God the Son, Jesus Christ. At the moment of Christ’s baptism in the Jordan, the manifestation of God took place — the Theophany.

O Most Holy Trinity, our God, glory to Thee.

- In what kind of God do Christians believe?

- What objects or phenomena of the visible world did the holy fathers compare the Trinity to?

- Name the Persons of the Holy Trinity.

THE ATTRIBUTES OF GOD

Man cannot see God, nor can he describe Him, yet some of God’s attributes are known to us.

God is eternal. God has neither beginning nor end. He was, is, and ever shall be.

God is omnipresent. He is present everywhere at once and fills all things with Himself. Just like the air that fills streets, homes, cars, or even a closed box on the highest shelf in a cupboard, so God is invisibly present everywhere, always near each one of us. We can turn to Him at any moment, wherever we may be, and He will hear us.

God is all-knowing. He knows all things, for He Himself created all things. He knows what clouds are made of, what the weather will be tomorrow. God knows what we do. He even knows what we think, though we do not say it aloud.

God is good. He always desires what is good for us, regardless of how we behave. A good father who wishes to raise his children to be wise and virtuous may sometimes punish them in order to correct and teach them. Likewise, God may at times chastise a person for his own good. A kind mother does not rush to give her child another candy, knowing that too many are harmful. So also God does not always grant our requests — precisely because He is good and knows what is truly beneficial for us and what is not.

God is the Creator. We can sense a spark of this creative nature in ourselves. We find it difficult to sit idle all day, doing nothing. We want to sculpt, glue, paint, build. In the same way, God, not remaining only within Himself, created the world around us.

God is the Almighty Ruler. All things in this world are under His authority. There are accounts of mountains being moved by His command, rivers changing course, storms calming, and even the dead being raised to life.

There is much injustice in our world. People dear to us, and truly good, fall seriously ill; wars rage in some places; innocent children perish. Does this mean that the Almighty God cannot stop it all? Of course He can. But such injustices arise from man himself, and the long-suffering and just God waits for man to correct these wrongs by his own free will. God the Provider sees not only the present but also what lies ahead. Sometimes He permits a small sorrow in order to prevent a far greater disaster in the future.

- List the main attributes of God

- Where does God dwell (where is He found)?

- What miracles are possible for God?

THE CHURCH — THE HOUSE OF GOD, THE FAMILY, THE HUMAN PERSON

When we hear the word church, we usually picture a majestic building with domes and crosses atop those domes. It may be made of wood, brick, or some other material. It is a place where people come to pray.

A church is a building intended for divine services.

Churches are built in a special way, unlike other buildings. Most often, a church has the shape of a cross or a ship. The cross is a special symbol of salvation for every Christian. The ship is likewise a symbol — of a safe place. One can say that the church is a spiritual ship in which we travel across the sea of life.

The number of domes on a church also carries specific meaning. One dome symbolizes our One Lord, Jesus Christ. Two domes represent the two natures of the Savior — divine and human. Three stand for the Most Holy Trinity. Four — the number of the Gospels. Five — Christ together with the four Evangelists. Seven domes remind us of the seven sacraments of the Church.

The church is a place of God’s special presence. When someone is very dear to us, we take every opportunity to be with them — we go to visit them. In the church, it is God who welcomes us like a kind host. Of course, God is everywhere — in the street, at home, in school, even in the supermarket or at the playground. But the church is the place where it is easiest to turn to God with prayer and thanksgiving.

The Church is also the gathering of believers.

Each of us has probably seen abandoned or half-ruined churches. Even when empty, a church does not cease to be a holy place. Yet without people, it loses its purpose. A church that no one visits gradually falls into ruin.

The family is a special community. It is where people live who are closest and dearest to one another. The family is often called a little church. In the sacrament of marriage, husband and wife become as close to one another as Christ is to the Church. The family is a little church.

During the Sunday service in Great Lent, a prayer is sung:

Open unto me the doors of repentance, O Giver of Life,

For my spirit rises early to Thy holy Church.

I carry the temple of my body, all defiled.

But do Thou, in Thy lovingkindness, cleanse it by Thy mercy.

In this prayer, the word church appears twice. In the first instance, it means the temple of God. In the second, it refers to the church of our body. The human being — with eyes, hands, ears — is also a church, because the Holy Ghost dwells in him. In the sacrament of Communion, God likewise takes up dwelling in the temple of our body. And so, the bodily temple must always be kept clean and radiant.

Just as we wash, clean, and decorate the prayer space for feast days, so too must we strive to keep our body clean and orderly — modest, yet neat in our clothing.

And if something breaks in a church building, we make every effort to repair it quickly and restore everything to its proper state. In the same way, the church of our body needs care and attention when it falls ill. It is God’s creation. Many habits of the modern world — smoking, drug use, tattoos on the body — are sins precisely because they destroy the temple of our body, which was created to be a dwelling place for God.

- What shape do Orthodox churches have?

- Why can we call the human body a temple?

THE INVISIBLE WORLD

The Bible begins its account of the creation of the world with these words: “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.” We are accustomed to thinking of heaven as the blue expanse above our heads, with the sun and clouds by day, and the moon and stars by night. But in the Bible, a different heaven is meant. Heaven refers to the multitude of invisible spirits created by God to glorify Him.

The word angel in Greek means messenger. God commanded the angels to help mankind, to guard him, and to proclaim God’s will. Angels are invisible, but sometimes they have appeared to people in the form of radiant, beautiful young men. On icons, they are depicted with wings to show that they can fly very quickly — instantly — from one place to another. No distance, no house, wall, or high mountain can hinder them. Near their ears, angels are shown with ribbons, because they are always listening to God’s commands. In their hands they often hold flaming spheres — a symbol that they carry out the will of God.

Just as in life we meet people of different professions, so too among the angels are different ranks and roles. The countless number of angels is divided into nine ranks: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Powers, Authorities, Principalities, Archangels, and Angels.

There also once existed a tenth rank of angels. These angels, led by Lucifer (in Church Slavonic: Dennitsa), grew proud and rebelled against God. For this, they were cast down from heaven.

These fallen angels, these evil spirits, are called demons. They retain the same properties that angels have: they can move swiftly through space, overcome obstacles, and do not have bodies — but they have become fixed in evil. For them, repentance and correction are no longer possible, as it is for human beings. They hate mankind and constantly try to lead people into sin.

Holy Archangels and Angels, pray to God for us!

- What does the Bible mean by the word heaven?

- How is the word angel translated?

- How many angelic ranks did God create? List them.

- Who are the demons?

- What is the purpose of angels?

- Is repentance possible for demons?

GUARDIAN ANGEL

At Baptism, God gives each person a guardian angel. This angel invisibly accompanies the person throughout life, protects him from harm, and guides him toward good deeds. When a person dies and his soul is separated from the body, the guardian angel accompanies the soul on its journey to God. At that time, the demons recall all the person’s evil deeds, while the angel, by contrast, tells of the good deeds — of prayer, almsgiving, and repentance.

In earlier times, it was customary at baptism to name the infant after the saint whose feast was celebrated on that day. That day was called a name day, or angel’s day. Today, name days do not always coincide with the day of baptism, but the day commemorating the saint whose name a person bears is still called his angel’s day.

The heavenly patron whose name the Christian bears is prayed to alongside the guardian angel. For a Christian, the angel’s day is even more important than a birthday — it is the day of spiritual birth, a birth into eternal life. Name days are determined according to the Church calendar. To find it, one must look for the closest feast after the person’s birthday that commemorates the saint whose name he bears. The celebration of the angel’s day should above all be spiritual. Prayer is especially important on this day.

On icons, the guardian angel is depicted with a sword and a cross. He holds a sword because he fights alongside the Christian against demons. The cross is also a weapon against invisible enemies and a sign that the one protected by the angel is a Christian.

Angel of Christ, my holy guardian,

save me, thy sinful servant.

- What is an angel’s day (name day)?

- How can one determine the date of their angel’s day?

- Why is the angel’s day no less important than a birthday?

- What do the cross and the sword in the guardian angel’s hands on an icon symbolize?

MAN IN THE WORLD

First, God created the invisible world of angels. Then the visible world came into being. Forests and gardens grew upon the earth, birds began to sing, the seas were filled with fish, and animals roamed the fields. But this beautiful world lacked a steward — someone who would care for God’s creation and rejoice in the beauty He had made.

Man was conceived by God to glorify the Creator, just like the angels. However, unlike the angels, man was to be visible and tangible. God took earth and formed a human body from it, then breathed a soul into the man. Thus, Adam came into being. God placed him in a wondrous garden called Paradise.

God brought the animals and birds to Adam, and showed him the grasses and trees. Adam had an astonishing ability to see and understand how and for what purpose each flower, animal, and bird had been created by God. He gave names to every creature in God’s creation. The first man received a commandment from God — to tend the Garden. He conversed with God, but among all creation there was no one like him. The animals had bodies, but could not speak. Adam could turn to the angels, but they were bodiless — and therefore not like him either.

So that Adam would not feel alone, God decided to make a helper for him. He caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, took one of his ribs, and from it created a wife for Adam. When Adam awoke and saw a person like himself, he rejoiced greatly. He called his wife Eve.

The first people were immortal. They never became sick, never grew tired, and did not suffer from hunger or thirst, heat or cold. According to God’s plan, in time they were to become firmly established in goodness, just like the angels — to grow even more perfect and to fill the place of the fallen tenth rank of angels. To test their will and obedience, God gave them a commandment: not to eat the fruit from one of the trees growing in Paradise — the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

- What were the names of the first people?

- What commandment did the first people receive from God?

- What did Adam have in common with the animals?

- In what way was Adam like the angels?

SIN

The devil envied Adam and decided at all costs to deprive him of the glory and honor given to him by God. The envious one took on the form of a serpent, came to Eve, and said, “Is it true that God has forbidden you to eat the fruits of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil?” “Yes,” said Eve. “We may eat the fruit of any tree, but only from the tree that grows in the midst of the garden God has forbidden us to eat, lest we die.” Then the devil began to deceive Eve, saying, “No, you will not die, but if you taste the fruit of that tree, you will become like gods, knowing good and evil.” Eve looked at the tree, and its fruit seemed good for food; she plucked one and tasted it, and then gave it to Adam. Thus, the first sin was committed on earth—disobedience, the failure to obey the will of God.

Adam and Eve were ashamed. However, they did not call upon God to ask for forgiveness, but hid themselves in the thick of the garden. God, of course, knew about Adam’s sin. He called Adam and asked, “Why did you hide? Did you eat of the tree from which I commanded you not to eat?” But even then Adam did not want to admit his guilt. He said, “It was the woman whom You gave me—she gave me the fruit, and I ate.”

God cast the first people out of Paradise and punished them. Their bodies were changed. They became subject to sickness and death. The world around them also changed—enmity appeared in it. Animals began to hunt one another. The winds and storms brought much harm to nature. Weeds and thorny plants appeared, which had not existed on earth before.

The stain of Adam’s transgression fell upon all generations of people thereafter. They could no longer avoid sin, for they were deprived of God’s grace. Their lives were doomed to end in death. The body returned to the earth from which God had once made the body of the first man. The immortal soul, which God had breathed into man, descended into hell—a dark place, deprived of God’s light.

Was God not sorrowful for His creation? Could He not simply forgive Adam and allow him to remain in Paradise? Of course, God grieved for mankind. But man had voluntarily turned away from God and had to labor himself to repair what he had done.

By himself, man could not return to Paradise. Divine help was necessary. God promised Adam and Eve that after many years a Savior would come to the earth, who would free humanity from sin and return to them the lost Paradise.

- For what reason did God expel Adam and Eve from Paradise?

- What changed in the first people after the fall into sin?

- What promise did God give to Adam and Eve before their departure from Paradise?

CHRIST – THE SAVIOR OF THE WORLD

Let us imagine that our friend is in trouble. He has fallen through the ice and cannot free his leg. No matter how much we worry for him, we cannot help him by merely standing far away and feeling sorry for his plight. We will only save him if we come close and extend a helping hand. In the same way, in order to help mankind and save it from eternal death, God also had to come to where dying man awaited Him: to descend to the earth and go down into hades.

To save mankind, God had to become incarnate—that is, appear on earth as an ordinary man. And so it happened.

Among the people of the earth, the Lord chose a pure Virgin, dwelt within Her, and was born like an ordinary man. He was named Jesus, which means “Savior.” Thus did God come to the earth. He too suffered hunger and cold, grew weary, and felt pain. He was like us in all things except one—there was not a single sin in Him. He taught goodness, healed the sick, and raised the dead.

But the descendants of Adam did not recognize in Him the Savior who had been promised to them. Out of envy and pride, they betrayed Him to a terrible death upon the cross. Every human being, without exception, after death had his soul descend into hades. Upon each soul was the mark of sin, and hades accepted these souls. The soul of Christ also descended into hades. But hades could not receive the soul of the God-man, for in God there is no sin, and there cannot be.

Christ entered hades as its Master, and He led out from there Adam and all the descendants of Adam who had been awaiting Him there for centuries.

From that time forth, every person has the possibility, at the end of their earthly life, to enter the Kingdom of God. One who believes in Christ is called a Christian—that is, a person who believes in Christ and lives according to His commandments.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

THE CROSS OF THE LORD

The first man, Adam, could not keep even the one commandment God had given him. He disobeyed God and ate the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Because of this, the mark of sin fell upon him and all who came after him. No matter how hard people tried, they could not live without sin. No matter how good or kind they were, at the end of their life’s journey there was always death: the soul would separate from the body and go down to hades. The faithful Israelite people knew that one day a Savior would come into the world to deliver them from this inescapable fate after death.

And so Christ came into the world. He was a Man, like each of us. He also grew sad, felt sorrow, became hungry, could fall ill, and endured both heat and cold. He was like us in all things—but He was sinless. Christ performed many miracles and taught people love and goodness. But the evil and envious Jews were jealous of Him. They could not recognize God in this Man and crucified Him.

This happened in Jerusalem. Jerusalem was the capital of Judea—the land where the Israelite people chosen by God lived. In those lands, there was a cruel custom: criminals were executed by crucifixion. Those who stole, robbed, or murdered were nailed to crosses, and over the course of several days, they died in agony from pain, blood loss, and exhaustion.

Just outside the gates of Jerusalem stood the hill of Golgotha. One of its places was called the Place of the Skull. Tradition held that the first man, Adam, was buried there.

Upon Golgotha, three crosses were raised. Two were for the thieves, and one—for God, for Christ, for the Messiah whom the people of Israel had awaited for so many years as their King, yet did not recognize in the One who seemed to them but an ordinary Man.

The cross prepared for Christ was different from the others—there was a plaque nailed to it. The order to crucify Christ was given by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. He commanded that a tablet be affixed to Jesus’s cross bearing the charge against Him. Christ had been accused of calling Himself the King of the Jews. And so it was written: “Jesus Christ, King of the Jews.”

The terrible execution was carried out on the eve of Passover. The hands and feet of the three condemned men were nailed to the crosses. The pain they experienced is impossible to describe. Their hands and feet ached from the wounds; their heads spun and throbbed; in the heat they were tormented by thirst. Christ asked for water. Soldiers stood by the cross to keep order. Instead of water, one of them placed a sponge on a reed, soaked it in bitter vinegar, and raised it to the Savior’s lips.

And when Christ died, another soldier, to be sure He was truly dead, took a spear and pierced His side. From the wound came forth two streams—blood and water.

People were passing by on their way to Jerusalem for the Passover feast. They pointed at Christ and laughed: “He saved others, but He cannot save Himself!” The suffering Christ cried out: “My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me?” and gave up the Spirit.

At that very moment, darkness fell over the whole land, and the earth shook. In the Temple at Jerusalem, the veil which separated the altar from the sanctuary was torn in two. Many long-dead righteous ones rose from the dead, entered Jerusalem, and preached God.

The soul of Jesus Christ separated from His body—just as happens with every person who dies. His body remained on the Cross. And His soul, like the souls of all people at that time, went toward hades. Hades received all the dead without exception—for all had sinned. But then the sinless Christ came to hades. There was not a single sin in Him, and hades could not receive Him. Then Christ Himself entered hades and brought out from there all the righteous who had awaited His coming, and led them into Paradise.

From that time on, every person, by the life he lives, determines where his soul will go. The souls of people who live in worldly vanity, sin, and do not repent, fall into hades. But to the merciful, the kind, the compassionate, God grants eternal life.

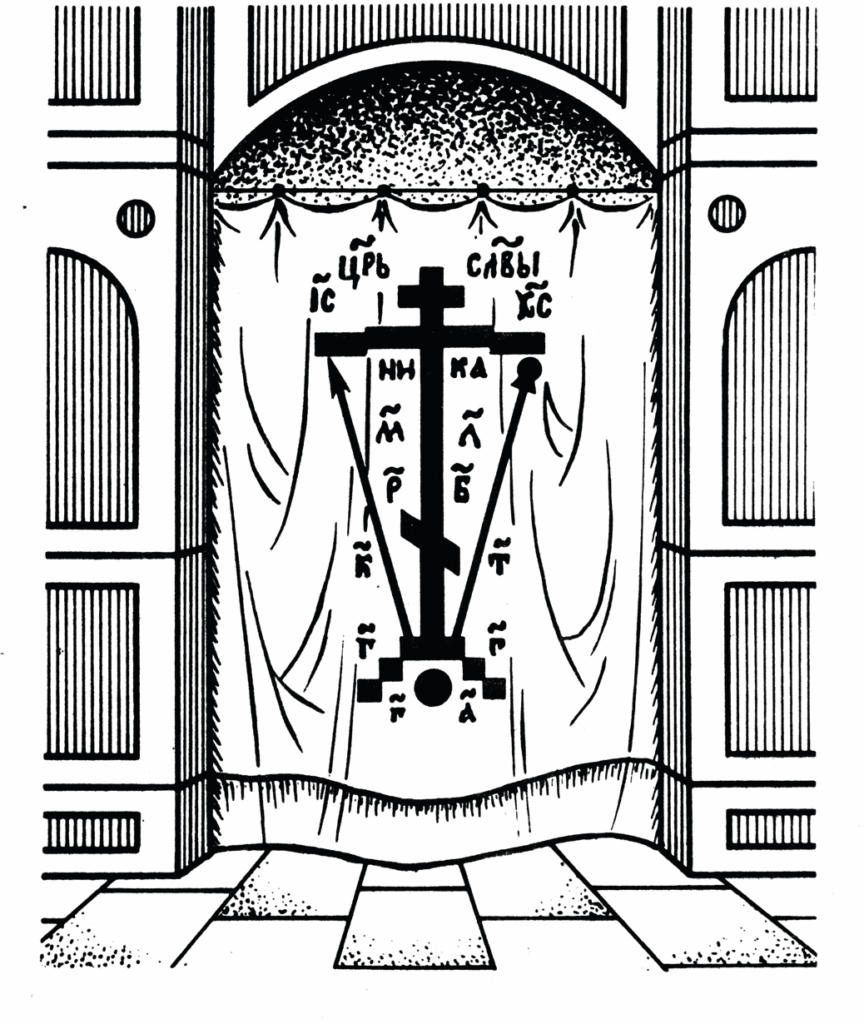

Next to the image of the eight-pointed cross, one may often see Church Slavonic inscriptions and letters. Their meanings are as follows:

- IС ХС — Jesus Christ

- Царь Славы — King of Glory

- Сын Божии — Son of God

- НИКА — A Greek word meaning “conquer” or “be victorious”

- К — spear

- Т — reed – the instruments of Christ’s Passion

- МЛРБ — “The Place of the Skull was made Paradise” – a Church Slavonic phrase expressing that the death of the Son of God on the Cross opened the way to the Heavenly Kingdom

- ГГ — Mount Golgotha

- ГА — Head of Adam

Glory, O Lord, to Thine Honourable Cross

ON THE SIGN OF THE CROSS

Every day, every moment, a Christian must struggle against his passions—the desire to do what pleases himself but is contrary to the will of God. It is not without reason that a Christian is called a warrior of Christ. And just as a soldier must go into battle armed, so too must the Christian have his own weapons: fasting, prayer, and the sign of the Cross.

The sign of the Cross is the making of a cross upon the body by a movement of the hand. To cross ourselves, we press together the index and middle fingers of the right hand, slightly bending the middle finger. These two fingers symbolize the two natures of our Lord Jesus Christ: His divine and human natures. The bent middle finger reminds us of God’s descent to earth and His incarnation.

The thumb, ring finger, and little finger are held together as a sign that we confess one God in three Persons—the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

When we trace the sign of the Cross upon ourselves, we first place the two fingers on the forehead, signifying that Christ holds the highest place in our thoughts. Then we touch the stomach, confessing that the Lord descended from heaven to earth. Next, we touch the right shoulder, proclaiming that Christ rose from the dead, ascended into heaven, and sits at the right hand of God. Finally, we touch the left shoulder, remembering the future second glorious coming of the Son of God and the Dread Judgment, when the sinners shall stand on the left side of the Lord.

The sign of the Cross should be made reverently, slowly, and distinctly, with special devotion. Our body should feel the touch of our fingers.

It is said of a carelessly made sign of the Cross that “such flailing brings joy to the demons.”

ON BOWS

Everything in our world happens gradually and in order. In early spring, first the branches come to life and the buds begin to swell. Little by little, leaves unfold, the buds gather color. Then the flowers bloom, and only by midsummer or autumn do the fruits ripen on the trees.

The ability to pray easily and with joy is also a fruit. And one must labor much for this fruit to mature.

There was once a monk, Elder John, who was very merciful not only to people but even to animals. One day, a peasant came to him, told him of his extreme poverty, and asked to borrow four rubles, promising to return the money soon. But two years passed, and the peasant did not come back to the elder. Meanwhile, the blessed elder heard that this debtor was living carelessly and was not even looking after his family.

One day he summoned the peasant and said:

— Brother, return the debt!

— God sees, said the peasant, I have nothing with which to repay you.

Then the elder said:

— I will help you repay it, if you listen to me in one thing.

— Whatever you say, I will do it, answered the peasant.

— Whenever you are free at home, come here to me and make thirty bows, and I will count out to you 18 kopecks each time.

The peasant gladly agreed.

And so he began to come often to the elder’s cell and make full bows along with him.

Some said to Elder John: “Why are you doing this? Are mere bows really of any use to such a lazy peasant? You’d be better off giving him a stern talk.” But the elder replied: “Wait until the end, then I will explain everything.”

As the peasant continued his bowing, the elder shared his meals with him like a brother and gave him dried bread to take home for his hungry family. At last, the peasant repaid his entire debt through bows. He had grown so accustomed to praying with bows at the elder’s cell that afterward he came of his own free will for prayer and shared bows. He no longer needed money, for from that time on, he began to live a sober and hardworking life.

“Why did you make the peasant do such a simple thing?” others asked the elder again. “Surely he knew his Christian duties without being told?”

— The spiritual life in him had gone cold, the elder replied. — But prayer revived his faith, and bows strengthened the spirit of piety in him.

Drop by drop, like life-giving rain, the spirit of prayer descends upon a person who practices bows.

A bow is a movement of the body that expresses reverence and respect. In prayer, there are waist bows, full prostrations (called great bows), and ground prostrations.

In a waist bow, one bends at the waist. In a ground prostration, one bends to the ground, touching the floor with the knees. In a full (great) prostration, one lowers to the knees in such a way that the forehead touches the palms placed on the ground.

When we pray before an icon—whether in church or at home—we usually first make the sign of the Cross, then bow. But sometimes we bow out of respect toward a person: a priest, bishop, or monk. In that case, we do not cross ourselves, because our bow is not part of prayer, but a sign of our reverence.

BLESSING

A human being consists of an invisible soul and a visible body. God has arranged it so that invisible grace is conveyed to the soul through visible actions and objects. The Holy Spirit touches our soul during the church service when the priest or deacon censes us and says: “The Holy Spirit shall come upon you, and the power of the Most High shall overshadow you.” Through the partaking of prosphora and holy water, our soul is strengthened and cleansed. One way to strengthen our soul and call upon God’s help in our good deeds is through blessing.

The word “blessing” (благословение) contains two parts: “good” (благо) and “word” (слово). A blessing is the bestowal of good by means of a word. This good comes from God and is passed on to us by a priest or bishop.

A blessing is an act performed by bishops or priests with the purpose of drawing down God’s grace upon a Christian. Forms of blessing include a spoken benediction, a cross-shaped gesture made with two fingers (the traditional Eastern blessing), a blessing with the sign of the cross using a hand-cross or icon, sprinkling with holy water, anointing with consecrated oil, and others.

If a person simply wishes to receive a blessing for the day—to live it in a Christian manner, free from sin and with spiritual benefit—it is not necessary to explain the reason. One may simply approach the priest, bow, and ask for a blessing. But there are occasions when a blessing is especially desirable or even necessary. It is customary to receive a blessing before important undertakings: the beginning of the school year, a long journey, or participation in a significant event. Every labor for the Church begins with a blessing: singing on the kliros, reading during the services, baking prosphora, ringing the church bells.

To receive a blessing in person from a clergyman, one should bow to the ground and say: “Forgive me for the sake of Christ, bless me.” The priest makes the sign of the cross over the person receiving the blessing and says:

“The blessing of the Lord God and our Savior Jesus Christ be upon the servant of God (name), always, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.”

Then he says: “Christ is in our midst.”

The one receiving the blessing should kiss the priest’s hand at the wrist. This is done out of respect for the sacred priesthood and in reverence for God, who gave the priest the authority to bestow the Holy Spirit.

Then one should bow to the ground once more and reply: “He is and shall be.”

These words affirm between the priest and the Christian receiving the blessing that Christ Himself invisibly dwells in their midst.

FASTING AND ITS MEANING

In order to learn to control his body well, an athlete must train constantly. To learn, for example, how to run far and fast, he has to do many different exercises: jumping, squatting, bending. Good results do not come right away. At first, the legs may not cooperate or cover a long distance quickly.

Learning to govern one’s soul also does not happen immediately. To learn to restrain anger, endure insults, and forgive others also requires constant training. One such exercise for the soul is fasting.

Fasting is a time for good deeds and abstinence from tasty food and pleasures. But how is abstaining from treats connected to training the soul? Here is how. A young Christian walks past a chocolate bar in the store on a fasting day. It’s tempting to grab it—he even has the money. But today is a fast day. He must restrain himself and say: “No, I’m a Christian, today is a fast. We’ll buy the chocolate another time.”

Another example: A young Christian is getting ready for bed—teeth are brushed, bed is made, evening prayers are finished. There’s a little time left before sleep. It would be nice to watch a cartoon. But the good child says to himself: “No, today is a fast. I’ll save the cartoon for another day; now I’ll read a book.”

And tomorrow, on the playground, some mischievous child may push our young Christian—whether on purpose or by accident. What should he do? Push back? No. Now he already knows how to say “no” to himself. Fasting teaches us self-control, how to make the right choice at the right time, even when that choice is difficult.

On fasting days, food is prepared without meat, milk, or eggs. Adults keep a strict fast; on some days, they neither eat nor drink at all. That is the strictest form of fasting. A little easier is the bread-and-water fast. Slightly more lenient is dry-eating, when one is allowed to eat uncooked foods: nuts, fruits, vegetables. Another form is a fast with cooked food but without any vegetable oil. The next step in leniency is when vegetable oil is permitted. And comparatively light is the fast when dishes with fish are allowed.

Children begin to fast when they turn three years old. Of course, they do not immediately adapt to a strict fast. Parents prepare them a varied and tasty plant-based diet. Yet one must not forget that fasting is an exercise in self-restraint. It should be manageable—a bit challenging, but truly possible to carry out.

FASTS THROUGHOUT THE YEAR

Fasting accompanies us throughout the whole year. There are 365 days in a year, and of these, about 200 are fasting days. Fasts may be single-day or multi-day. Throughout the year, we fast on Wednesdays and Fridays. On Wednesday—in remembrance of Judas’s betrayal of Christ. On Friday—in remembrance of the suffering and death of the Lord upon the Cross. Monks also fast on Mondays. This custom of “Monday-fasting” is kept by some devout laypeople as well.

The longer fasts prepare us for great feasts. Before Pascha, we keep the Great Fast (Lent). It is the strictest and longest fast. The Great Fast lasts forty days, and to it is added the fast of Holy Week. Before the feast of the Nativity of Christ, we keep the Nativity Fast. It also lasts forty days, but is less strict than the Great Fast: during most of the Nativity Fast, fish is permitted.

The Dormition Fast is the shortest but also strict. It lasts just two weeks, before the feast of the Dormition of the Most Holy God-bearer. Another fast is the Apostles’ Fast, also called the Peter and Paul Fast. It prepares us for the feast of the holy apostles Peter and Paul. Its beginning depends on the date of Pascha, but it always ends on July 12th, the feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

Fasting was given by God to man even in Paradise. In the beautiful garden of Eden, there were many bushes and trees, and the fruits of all of them could be eaten. But there was one tree—the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil—the fruit of which was forbidden. The first people broke this fast and were severely punished: the Lord cast them out of Paradise. We, the descendants of Adam and Eve, must fast in order to make our soul once again worthy of eternal life in Paradise.

The Bible contains many examples of how the righteous fasted. The prophet Moses ate no food for forty days—and the Lord spoke with him on Mount Sinai. The prophet Elijah also fasted long and strictly—and at his prayer, a terrible drought in the land of Israel came to an end. Even the Lord Jesus Christ fasted: after being baptized by John, He went into the wilderness and for forty days ate and drank nothing.

Fasting strengthens our soul, making it strong and capable of resisting sin. However, it would be wrong to think that fasting is only about abstaining from food. Fasting is also a time of prayer and good deeds. It is wonderful if, during these holy days, we are able to attend church more often, visit sick relatives, help our elderly and frail grandmothers and grandfathers, and do something kind for our parents, brothers, and sisters. Then our fast will be accepted by the Lord and bring benefit to our soul.

PRAYER AT HOME AND IN CHURCH

We love our mom and dad, our grandma and grandpa. And even if they are far away for some reason, we try not to let a day go by without talking to them on the phone. And on the other hand, if we don’t talk to a good friend for a long time, little by little we grow distant and start to forget about them.

Prayer is a conversation with God. And this conversation must happen every single day—otherwise, our soul, which is easily tempted by laziness, might grow cold toward our Creator. What should we talk to God about? The beginning of a new day is a reason to thank Him. We will spend this day with the people we love and learn many new and interesting things. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are also times to give thanks. God gives us the chance to be fed—and not everyone has always had that chance.

If we look back on our day before going to sleep, we’ll surely remember something we did or said that makes us at least a little ashamed. That’s a reason to ask God for forgiveness. We can also share our worries, dreams, and thoughts with Him. God is all-powerful, and if we ask for things that are good for our soul and truly needed in life, He will surely hear us and answer our prayers.

But God is invisible—so how can we hear His answer? That’s very important—not just to ask, but to be sure that Someone is listening. God always hears us. He knows not only what we ask out loud but even what we only think in our hearts. Pure and bright souls can hear God’s answer deep inside. Their hearts become calm and peaceful, their thoughts turn light and joyful—that is God’s answer. But to be able to hear Him, we must pray sincerely and with all our heart.

The red corner is a special place in the home where holy icons, oil lamps, and candles are placed. Icons help us imagine the One we are speaking to. Every Christian family has a little corner with icons at home. This corner is called red, which means beautiful. Among the icons are those of the Savior, the God-bearer, and the saints. The light of a candle or lamp helps prepare us for prayer, for a conversation with God.

PRAYER IN CHURCH

A special place for prayer is the church. At home, we say private, personal prayers. There, we mostly pray for our own needs: for the health of our loved ones and for ourselves. But in church, prayer is shared by all. At a church service, we pray for things that are important for everyone in the whole world: that there would be no war or natural disasters, that the earth would bring forth a good harvest, and that God would plant faith in the hearts of all people everywhere.

Sometimes when we ask our parents for something, they don’t always respond right away. But if we call out together, as a whole family, Mom is more likely to answer quickly. It’s the same with shared prayer. If not just one person, but two or three or more people ask for the same thing, God is more likely to fulfill their request. That’s why people often ask one another to pray for them.

We can speak to God at any moment—at home, on the street, even lying in bed before sleep. But the church is the best place for this conversation with God. The many icons, the candles, and the lampadas help turn our hearts toward prayer.

The church service tells us about God. The meaning of the prayers we hear is deep and beautiful, and each time we hear them, we can discover something new in the familiar words. In church, we are surrounded by people who believe as we do and are asking for the same things. That makes shared prayer especially valuable.

When Christians pray together, led by a priest, it is called a church service or Divine Service. It begins on the evening before a feast day and continues again in the morning after a night’s rest. The most important part of the service is the Divine Liturgy—that part of the worship during which the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ. It was the Lord Himself who commanded us to celebrate the Liturgy. On the night before His Passion on the Cross, He broke bread and gave it to His disciples. Then He gave them a cup of wine, telling them to do this in remembrance of Him.

After the prayers of the Liturgy, the bread and wine are no longer just ordinary bread and wine—they become the true Body and Blood of Christ. The priest gives them to those who come forward for Holy Communion. When someone receives Communion, Christ Himself comes to dwell within that person.

We know that God and sin do not go together. Where God is, there is no sin. That is why it’s so important to make sure our soul is clean before coming to Communion.

Little children receive Communion at every service. They are still too young to understand when they’ve done wrong, but they also don’t hold on to anger or resentment—they forgive very quickly. Older children are already able to keep watch over their thoughts and actions, to restrain themselves, and to recognize their mistakes. That’s why, just like adults, they prepare for Communion by confessing their sins and by fasting and prayer.

ABOUT CANDLES AND LAMPADAS

When we want to do something nice for someone we love, we give them a gift. To show love and thankfulness to the Creator, people have always brought offerings to God from what He has allowed them to have. The children of Adam and Eve—Cain and Abel—offered God a portion of the things they had worked for. Cain, who was a farmer, brought the fruits of the earth that he had grown. Abel, who was a shepherd, brought animals from his flock.

In the Old Testament, people most often brought animals and birds as offerings to God. These blood sacrifices reminded the world of the Great Sacrifice to come—of Christ, who would one day shed His Most Pure Blood for the sins of mankind. After Christ suffered on the Cross, people no longer brought animals, but instead bring bloodless offerings to church: oil for the lampadas and candles.

Candles are made from beeswax—the substance bees use to build honeycombs. The wax is heated until it becomes soft and thick, then poured into special molds. In the center of each mold is a wick, which soaks up the hot wax and stays inside the candle. When the wax cools, the candles are taken out of the molds.

The flame of the candle reminds us of Christ, who said that He is the Light of the world. A candle stands straight in front of an icon—just as we, too, should stand straight and reverent in prayer. The light of the candle inspires us to live pure and bright lives, and to bring light into the world through our good deeds. Just as wax softens and melts in the flame, so too does every bit of anger in our hearts soften and melt through prayer—like a candle.

The custom of lighting lamps and candles began long ago, in the first centuries of Christianity. In those days, rulers often punished and tortured people simply for believing in the Lord Jesus Christ. So Christians gathered for prayer at night. At first, candles were used just to light up the room. But very soon, they began to be lit not only for light, but also to express joy and spiritual celebration.

At the very beginning of a church service, only a few candles are lit. During festive moments, all the candles are lit. On great feast days, the faithful themselves often stand with lit candles in their hands.

A candle is our gift to God and to His saints, so we should handle it carefully and respectfully. We place a candle in front of an icon of the Lord or one of His saints, saying a prayer to the one shown on the icon, and hoping for God’s help.

A Reminder about Church Candles

You’ve bought a candle at church. Think about which icon you would like to place it before.

Listen closely to the service. Wait until the most important prayers are finished—during these moments, walking around is not allowed—or until the censing is done, when the priest or deacon walks around the church with incense. Then, quietly walk to the icon where you want to place the candle.

Cross yourself and bow while praying to the Lord or to the saint shown on the icon. Cross yourself and bow again, saying the same prayer. Then cross yourself a third time, and place the candle upright in the candlestand. After that, make one more sign of the cross and a bow.

If you want to place a candle at an icon in the iconostasis (the wall of icons at the front of the church), it is better not to step up onto the solea (the raised area in front of the iconostasis), but to give your candle to one of the choir members or helpers.

Make sure your candle stands up straight. If the candles in the church are not lit at that moment, leave yours unlit too—they will be lit at the proper time in the service.

Candles remain in their holders until they burn down almost completely. Only a small part of the candle is left—a stub, which is then removed and placed in a special box made for that purpose.

Remember: a burning-down candle is not a reason to disturb the prayerful atmosphere in church. Don’t rush to the candle stand to put out your candle during parts of the service when walking around is not allowed.

Treat candle stubs with the same care as the candle itself. Don’t play with them: don’t melt them down or mold them into little shapes.

Short Prayers before the Icons

Before the icon of the Savior:

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner!

Before the memorial table (for the departed):

O Lord, give rest to the souls of Thy departed servants!

Before the Cross:

Glory to Thy Precious Cross, O Lord!

Before the icon of the God-bearer:

Most Holy Lady God-bearer, save us!

Before the icon of the Guardian Angel:

O Angel of Christ, my holy guardian, save me, Thy sinful servant!

Before the icon of a saint:

Holy [Name of the Saint], pray to God for us!

MUSIC IN CHURCH

Among all the many sounds in the world, music makes a special impression on the human heart. Harsh and loud music stirs up anxiety. Aggressive music can be frightening. Calm and melodic music, on the other hand, brings peace and quietness to the soul.

Music is created using musical instruments—and the most remarkable instrument of all is the human being. A person can not only make individual sounds, but can sing words, adding meaning and depth to the music.

Prayer texts can also be sung. When they are, they sink even more deeply into the soul. The Gospel tells us that Christ Himself sang prayers. Long before His coming, the Prophet David lived. He composed an entire collection of songs of praise to God—the Psalter. After Christ, many other hymn-writers composed beautiful church hymns. One of the greatest among them, Saint John of Damascus, arranged these hymns into eight groups with similar melodies. These are known as the Eight Tones.

To write down melodies, special symbols are used called hooks (kriuki). That is why Old Believer chant is also called hook notation chant. The hooks show how the melody moves, how many notes there are, and how long each one lasts.

The singers in church stand at the kliros. The kliros is the place in front of the north and south doors of the altar, often marked off by a screen with icons.

Church singing is done in unison—all members of the choir sing the same melody together. This principle of unison singing makes the words of the prayers easier to understand, which is very important. A person in church should not only be moved by the beauty of the music, but also understand the meaning of the prayer.

BELL RINGING

A special kind of church music is bell ringing. Church bells are shaped like bellflowers, and that’s why they have a similar name. The ringing of the bells calls the faithful to church services. During the service, the bells are rung several times in different ways—this lets those who, for serious reasons, cannot be in church know when the most important parts of the service are happening, so that they too can pause and turn their hearts to prayer.

Bells first appeared in the West in the 5th century, in the Roman province of Campania. That is why, in some languages, the word for bell comes from there—for example, campana. In Orthodox churches at that time, people used to call the faithful not with bells, but with semantra—wooden boards or iron plates—called bila and klepala, which were struck with a hammer. Bells gradually replaced these earlier instruments.

There are several different types of bell ringing. The blagovest is a steady, measured ringing of a single large bell. It calls the faithful to God’s house and signals the beginning of the service. After the blagovest, and before festive services, there may be a more joyful ringing using multiple bells—or a triple peal called the trezvon.

On major feast days, a special kind of ringing is done called the chime or peresvon, where several bells are rung one after another—not all at once, but in sequence, starting with the smallest and moving to the largest.

The person responsible for bell ringing in church is called the bell ringer—in Russian, the zvonar’.

THE ICON

Before the coming of Christ, there were no images of God. God Himself had forbidden people to make any image of Him. And how could anyone possibly depict the One whom no one had ever seen? But people were able to see God in Jesus Christ when He came down to earth and took on flesh. Of course, even then, God did not appear in the fullness of His divine glory. But still, we can boldly say that those who saw Christ saw God Himself.

Tradition tells us about a certain king named Abgar who lived at the time of Christ. Abgar fell seriously ill. He had heard of the many miracles Christ performed and sent his servant to Him. The king did not dare trouble Christ with a request to come heal him—he lived far away. But he asked his servant to at least paint an image of Jesus Christ. The king believed that even Christ’s image would help ease his illness. Christ knew of Abgar’s need. He washed His face, took a clean cloth (called a ubrus), and wiped His face with it. His divine face left an imprint on the cloth. The servant brought the ubrus to Abgar, and the king was healed. It is believed that this cloth, bearing the face of Christ, was the first icon.

The writing of icons was blessed by the God-bearer Herself. The Apostle and Evangelist Luke was a skilled painter. One day, he decided to paint an image of the Mother of God. She was pleased with the Apostle’s work and blessed the icon, saying, “With this image shall My grace and power be.” Thus began the tradition of icon writing.

The word icon comes from Greek and means image. An icon is a depiction of the Lord, the God-bearer, angels, or saints. Saints are not shown in icons the way ordinary people look in life. People say that icons are not painted, but written. The face of a saint in an icon becomes a holy countenance. The iconographer strives not to create a portrait, but to show the inner richness and holy labors of the one being depicted.

Icons are written according to special rules. First, the iconographer selects and prepares the wooden board. Then he applies a special white layer called levkas. On this layer, a sketch is drawn—the outline of what the icon will show. Only after this does the iconographer begin working with paint. This process is long and careful. It is done slowly, and with prayer.

In addition to painted wooden icons, there are cast-metal icons made from copper. To make one, a mold is first created with the image of the saint. Then molten metal is poured into the mold.

Every icon is the result of someone’s labor, and for that reason, each one is unique and valuable. Icons must be treated with care and reverence. We should not touch icons unnecessarily. And if, for example, an icon must be moved during cleaning, it should be laid on a clean cloth or towel.

Until the 9th century, there were sometimes disputes about whether icons should be written at all. Opponents of icon veneration pointed to the Old Testament commandment forbidding worship of images. They called icons idols and accused those who venerated them of idolatry.

But an idol is an image of a false god—that is, of a demon.

The holy Fathers declared that icons are true images of the saints. Christians do not honor the materials—wood, paint, and so on—but rather, they honor the saints depicted on the icon. This honor is shown by lighting lampadas and candles before the icons, by bowing and kissing the icons, and by anointing them with oil from the lampadas.

Sometimes, by God’s power and through the prayers of the saint shown on the icon, special miracles take place near certain icons in response to the faithful’s needs. These icons are called wonderworking. The healing and saving power of these images is not in the wood or paint, but in the prayer of the saint to whom we offer our prayer before the icon.

THE DEPICTION OF GOD IN ICONS

It is impossible to depict the invisible and incomprehensible God as He truly is. There is no material in the world, no image or method capable of expressing the Creator in an icon. However, the Holy Fathers judged it acceptable to portray God as He revealed Himself to people.

In the Old Testament, God appeared to Abraham in the form of three angels. This moment is preserved in the icon The Old Testament Trinity. On this icon, three angels are shown sitting under a tree at a table. The angels symbolize the Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. In their hands they hold long staffs—symbols of divine authority. The tree reminds us of the Tree of Life that grew in Paradise. At the center of the icon is a table with a chalice, which symbolizes the cup of suffering that Christ would later endure.

We see the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost again on the icon of The Theophany (the Baptism of the Lord). The Son is shown standing in the River Jordan, receiving baptism from John the Forerunner. The Father is depicted by a semicircle at the top of the icon. From this semicircle comes a ray of light, and in that ray descends a dove, which symbolizes the Holy Ghost.

There are many more icons in which only the Savior is depicted. These include icons of the Crucifixion, icons of Christ the Almighty (Pantocrator) holding the Gospel, and Christ in Glory seated on the throne and surrounded by angels. One detail is common to all icons of Christ: a special type of halo. Like the other saints, Christ is shown with a circular radiance behind His head. But His halo includes the shape of a cross behind it. On the three arms of the cross are written the Greek letters ὁ ὤν (HO ON), which mean The One Who Is—that is, the One who exists eternally. Also, next to every icon of Christ are the letters IC XC, a shortened Slavic form of Jesus Christ.

A halo is the circle of light around the head of a saint, symbolizing holiness.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

THE GOD-BEARER

The Gospel says little about the Virgin Mary. But the first Christians preserved memories of her and wrote down the testimonies of those who had seen her:

“She was of medium height, her hair the color of ripe wheat, her face bright, her eyes clear, her lips rosy. She wore simple clothing, spoke little, and was always kind. Every word she spoke breathed with grace.”

When the child Mary was three years old, her parents, Joachim and Anna, brought her to the temple. There, she lived until the age of twelve. She spent her days doing needlework, studying the Holy Scriptures, and praying constantly. The Virgin made a vow never to marry. When she turned twelve and could no longer remain in the temple, she was betrothed to the elder Joseph, who was chosen to guard and care for her.

It was in Joseph’s house that the Archangel Gabriel once appeared to the Virgin Mary and announced to her that she would become the Mother of the Incarnate God. The humble Mary replied: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord. Let it be unto me according to thy word.” Then the Holy Ghost came upon her, and she conceived the Savior. By God’s command, Mary named her Son Jesus. She cared for Him as a child, and when the grown Jesus began His preaching, His Most Pure Mother was always close by. She, too, listened to His divine teaching and helped wherever she could—preparing food, clothing, and arranging places to stay.

She followed her Son to His crucifixion and stood at the foot of the Cross. According to tradition, Christ appeared first to her after His Resurrection. Together with the Apostles, she preached the Gospel.

When the time came for her to leave this world, something wondrous occurred: the Apostles, from all corners of the earth, were brought to her on the clouds—except for the Apostle Thomas, who arrived later. The God-bearer bid them farewell, gave them her blessing, and peacefully gave her soul to God. Her departure into eternal life is called the Dormition and is celebrated as a great feast. When the Apostle Thomas arrived and wished to venerate her body, the tomb was opened at his request—and her body was no longer there. The Lord had taken His Most Pure Mother into the Kingdom of Heaven with her body.

Prayer to the God-bearer:

It is worthy for in truth to bless thee, O God-bearer…

There are perhaps even more icons of the God-bearer than of the Savior. Many of these icons appeared in miraculous ways near towns and villages. According to where the icon was revealed, or where it became known, each image of the God-bearer receives a special name: Smolenskaya, Tikhvinskaya, Vladimirskaya, Kazanskaya.

All icons of the God-bearer have one thing in common: her crimson garment. Upon her clothing are three symbolic stars. The star on her forehead represents her purity at the time of Christ’s birth. The star on her right shoulder symbolizes her purity before His birth. And the star on her left shoulder represents her virginity after the birth of Christ.

SAINTS – THOSE WHO INHERITED ETERNAL LIFE

Besides the Lord Himself and His Most Pure Mother, the Church also honors those people who lived righteously on earth and were found worthy of eternal life. Different saints became known for different labors: some preached the word of God and worked to strengthen the Church of Christ; others were glorified through their theological writings, some were given the gift of foresight, and many suffered for their faith. Even after departing this earthly life, these people have even greater boldness before God and intercede for us when we ask them for help.

Saints are people who lived a righteous life, pleased God, and entered into the Kingdom of Heaven.

How can we know that someone who has died has become a saint? There are several signs. There is no doubt about the holiness of those who gave their lives for Christ—who chose to die rather than deny their faith. The bodies of some saints remained incorrupt after death—that is, they did not decay or break down.

A life (or “vita”) is a written account of a saint’s life.

In honoring the saints, the Church has appointed special days to remember each one during the year. These days usually fall on the date of the saint’s death, or the date of some important event in their life, or the discovery or translation of their relics.

Canonization is the process by which the Church officially recognizes someone as a saint.

Among the great host of saints are apostles, prophets, martyrs, hierarchs (bishops), monastic saints (ascetics), and righteous ones. When we glorify the saints, we are also glorifying the Lord Himself, who honored His faithful ones with such holiness and miracles.

The Synaxarion (or Saints’ Calendar) is a list of saints’ names arranged by the day of the year when each one’s memory is celebrated, along with the Church feasts.

Relics are the incorrupt remains of a saint.

Many miracles have taken place through the relics, graves, or personal items of saints. Sometimes saints appeared in dreams to devout people and revealed the will of God. Such saints were first honored by the people, and then officially canonized by the Church: an icon of the saint would be written, their life recorded, prayers composed in their honor, and sometimes entire church services written for them.

THE APOSTLES

At the highest level of the Church’s hierarchy of saints stand the Apostles. Not only did they themselves attain eternal life, but they also led thousands of people into the Kingdom of God. The word apostle comes from the Greek and means “messenger” or “one who is sent.” These were the closest disciples and followers of Jesus Christ, who preached the Gospel and helped establish the Church. Even during His earthly life, Christ sent them out to proclaim His teaching to the world. After His death, Resurrection, and Ascension, the Apostles went beyond the borders of their homeland to bring the good news of God to all nations.

From among His disciples, the Savior chose twelve: Peter, Andrew, James the son of Zebedee, John the son of Zebedee (the Theologian), Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Matthew, James the son of Alphaeus, Lebbaeus Thaddeus, Simon the Zealot, and Judas Iscariot. After Judas fell away, Matthias was chosen to take his place among the twelve Apostles.

In addition to the twelve main disciples, there were also seventy others who labored alongside them in preaching. These are called the “Seventy Apostles.” The well-known Apostle Paul was not one of the seventy. Before coming to the light of faith, Paul was known as Saul. He was a very educated man who sincerely did not believe in the resurrection from the dead, and so he did not understand the Christians and persecuted them.

One day, Christ Himself appeared to Saul in a blinding light and reproached him for persecuting Him. From the brightness of the vision, Saul lost his sight. His vision returned after he was baptized, and he immediately set out to preach the Gospel. At his baptism, Saul was given the name Paul. The Apostle Paul founded many Christian communities among the Gentiles, and for this reason he is called the “Apostle to the Gentiles.” Like nearly all the other Apostles, Paul also died a martyr’s death—he was beheaded with a sword.

Among the Apostles, four are especially distinguished as the authors of the four Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John the Theologian. These are called the Evangelists.

An apostle is a close disciple and follower of Jesus Christ, who preached the Gospel and labored in establishing the Church.

Preaching means explaining the Christian faith.

In icons, the Apostles are depicted in simple clothing, wearing sandals, and holding a scroll or a book in their hands. The sandals show that the Apostles were always on the road, going from city to city. The book symbolizes the teaching of Christ. The Apostle Peter is often shown holding keys in his hands. A characteristic feature in depictions of the Apostle Paul is the presence of only a little hair on his head.

Above the Royal Doors in the church is an icon of the Mystical Supper, where all twelve Apostles can be seen. This icon shows the moment when Christ established the Mystery of Communion. Among the icons of the great feasts is the icon of the Descent of the Holy Ghost, where the twelve Apostles are also shown together.

The Holy Church gives the name “apostle” only to the immediate disciples of Christ. Those saints who lived after Christ but undertook labors similar to those of the Apostles are called Equal-to-the-Apostles. Among them are the great Prince Constantine and his mother Helen, who found the Holy Cross of the Lord; the saints Cyril and Methodius, creators of the Slavic alphabet; the first baptized Russian princess, Olga; and her grandson Prince Vladimir, who made the decision to baptize Rus’.

Holy apostles, pray to God for us.

THE PROPHETS

After the expulsion of Adam from Paradise and until the coming of the Savior to earth, faith often weakened among people. They would forget the true God, begin to worship idols, and commit countless sins. But God did not allow the true faith and knowledge of Him to disappear completely. He chose from among mankind the most worthy individuals and, through the Holy Spirit, revealed to them His commandments and the future destinies of the human race. These individuals were called prophets.

A prophet—which means “foreteller, predictor”—is a holy person who proclaims to others the commands of God revealed to him by the Holy Spirit.

Yet not all people during the prophets’ lifetimes listened to them. Many laughed at the prophets, mocked them, humiliated them, and some were even killed—such was the people’s hatred of being rebuked and corrected in their corrupt ways. The prophets foretold the coming of Jesus Christ to earth, His crucifixion, resurrection, ascension into heaven, His Second Coming, the resurrection of the dead, and the dreadful judgment.

The prophet Jonah became a symbol of Christ’s three-day resurrection even through his own life. Jonah received a command from God to go to the city of Nineveh and preach repentance, warning that the city would be destroyed because of its inhabitants’ sins if they did not repent. But instead of obeying God’s command, the prophet boarded a ship and sailed away on a long journey.

The ship he sailed on was caught in a storm. In fear, the sailors cast lots to discover whose sins had brought down the wrath of God upon them. The lot fell to Jonah. He confessed that he had disobeyed God’s command and asked the sailors to throw him into the sea. In the depths of the sea, a great whale swallowed Jonah. For three days Jonah remained in the belly of the whale, praying. And God caused the whale to spit Jonah out onto dry land. Just as Jonah was in the belly of the whale, so Christ was in the tomb for three days, and then rose again.

The books of the prophets form part of the writings of the Old Testament. Four of them belong to the great prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel. Twelve are by the lesser prophets: Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.

In icons, the prophets are depicted holding scrolls in their hands. These scrolls bear words from their prophecies. In churches with high domes, where a tall iconostasis can be placed, the top row of the iconostasis consists of icons of the prophets—this is known as the prophetic row of icons.

Holy prophet Isaiah, pray to God for us.

HOLY MARTYRS

Unfortunately, not everything in the history of our Church has been peaceful and prosperous. There were times when believers were persecuted—even put to death. Such harsh times began immediately after the Resurrection of Christ from the dead.

Faith in the Resurrection of Christ and His teaching about love and goodness seemed absurd to many. The world around them was pagan.

Pagans are people who, instead of believing in the one true God, worship idols and deify natural phenomena, celestial bodies, animals, trees, stones, and other objects.

Even kings and emperors believed in pagan gods, celebrated pagan festivals, and offered sacrifices to idols. Christians could not and would not participate in such rites, for they knew the true God and, in the mystery of baptism, had pledged to serve Him alone. Christians were arrested, starved in prisons, tortured, thrown to wild hungry beasts, burned with fire, and subjected to many other forms of execution. But Christ strengthened the suffering believers and worked many miracles through them. Those who drank poison remained unharmed. The fire of a burning furnace did not harm them. They were miraculously healed of their wounds. These miracles inspired and strengthened the faith of those who witnessed their torture and execution.

Christians who gave their lives for professing the faith during persecutions were called martyrs. The word martyr comes from Greek and means witness. These saints bore witness to Christ and went to their deaths with that testimony. In icons, martyrs are easily recognized by the cross they hold in their hands. This cross symbolizes the martyr’s confession of faith in Christ.

Those martyrs who endured especially fierce persecutions and torments are given the title Great Martyr. Those who suffered for the faith but remained alive are called Confessors. Martyrs who were ordained as bishops, priests, or deacons are called Hieromartyrs.

Fellow believers carefully gathered the bodies of the holy sufferers and buried them with honor. Prayers were offered at the graves of these saints. The tradition of celebrating the Divine Liturgy on the relics of holy martyrs continues to this day. In the altar of every church stands the Holy Table (altar), upon which the Liturgy is celebrated. On the Holy Table lies a special cloth called the Antimension. According to ancient tradition, relics of holy martyrs are sewn into the Antimension.

Where do these relics come from? Some of the martyrs were tortured so severely that, after their deaths, it was not always possible to recover all their bodily remains intact. Thus, their relics ended up naturally divided. Some of the relics would be preserved in one church, and others in another. Sometimes saints would appear to people in dreams and instruct them to divide their relics so that believers could venerate them. Even from the smallest fragment of relics, miracles and healings were worked. Soon, the practice of dividing relics became a Church tradition.

- A reliquary (raka) is a chest or box containing the relics of a saint.

- A small reliquary (moshchevik) is used to store smaller pieces of relics.

Holy Martyr Uar, pray to God for us.

Holy Great Martyr Mina, pray to God for us.

Holy Hieromartyr Kharalampi, pray to God for us.

HOLY BISHOPS (HIERARCHS)

The period of early persecutions against Christians was followed by a time of peace, during which the faith spread rapidly across the world. In addition to the four Gospels and the teachings of the holy apostles, new writings by the holy fathers began to appear. The responsibility of explaining the Gospel rested chiefly upon the highest rank of the clergy—the bishops. They clarified Church doctrine and affirmed many in the true faith. Disputed matters of belief were resolved sobornically, that is, by council.

After prayer, priests and bishops would gather to study the Holy Scriptures, discuss, and reach a decision. The Holy Ghost guided their thoughts and hearts toward the right conclusion. Thus arose in the Church the tradition of conciliarity (sobornost’), which continues to this day—the making of important Church decisions by common assembly.

The Church has glorified as holy bishops those outstanding preachers who lived righteously on earth and were received into heaven.

Holy bishops (or hierarchs) are the heads of the Church—bishops who labored to establish the faith of Christ and His Church on earth.

Among the most well-known of the holy bishops are John Chrysostom, Basil the Great, and Gregory the Theologian. These three left behind a great number of works: teachings, commentaries, homilies, and letters. Basil the Great and John Chrysostom are also the authors of the prayers used in the Divine Liturgy that we hear to this day.

In icons, a bishop is easily recognized by his vestments. Over his shoulders is placed an omophor marked with crosses.

The omophor (from the Greek for “shoulder covering”) is part of a bishop’s vestments in the form of a wide band laid across the shoulders. It symbolizes the “lost sheep”—that is, the sinful human race—which the true Shepherd, Jesus Christ, found and is saving from ruin by carrying on His shoulders.

A particularly notable icon among the hierarchs is that of St. Nikola. His curly beard and hair reflect his appearance in life. Near this saint, Christ is almost always depicted holding the Gospel, and the God-bearer (Mother of God) is shown with the omophor in her hands. These images recall an event from his life.

At one of the Church Councils, Nikola was debating with Arius about Christ. Unable to endure Arius’s blasphemy, Nikola struck the heretic on the cheek. The Council Fathers regarded this act as an excess of zeal and removed St. Nikola from the episcopal rank, taking away his vestments and confining him to a prison tower. That night, many of them had a vision: the Lord Himself gave the Gospel to St. Nikola, and the God-bearer placed the omophor upon him. Then the man of God was released from prison and restored to his former office.

O holy hierarch of Christ, Nikola, pray to God for us.

MONKS AND RIGHTEOUS ONES

Among Christians there were especially zealous souls for whom the mere observance of fasts and commandments seemed insufficient. Their souls yearned for a greater spiritual struggle. Such people left the world, gave all they had to the poor, and withdrew to deserted places: deserts, mountains, forests. Thus monasteries were formed and monks appeared.

Far from the bustle of worldly life, they could devote themselves entirely to prayer. By their holy lives, they became like the angels and even like Christ Himself. Therefore, they are called monks (literally: “those who have become like”).