The Solovetsky Resistance

K. Kozhurin.

(On the 350th anniversary of its beginning)

In 1668, the siege of the principal holy shrine of the Russian North—the Solovetsky Monastery—began by tsarist troops. From the very start of Patriarch Nikon’s reforms, the monastery had become one of the chief strongholds of the old faith.

“The Solovetsky Monastery was the fourth most important monastic house in northern Rus— the first outpost of Christianity and Russian culture in the harsh Pomor region, in the ‘wild Lapp lands,’ which both preceded and directed the flow of Russian colonization… The venerable fathers Zosima and Savvatiy endured an extraordinarily harsh life on the island, yet already Zosima, the true organizer of the monastery, appears to us not only as an ascetic but also as a diligent steward who determined for centuries the character of the northern abode. The union of prayer and labor, the religious sanctification of cultural and economic endeavor, marks the Solovki of both the 16th and 17th centuries. The richest landowner and merchant of the Russian North, from the end of the 16th century also a military guardian of the Russian shores (a first-class fortress), the Solovki even in the 17th century continued to give the Russian Church saints.”[1]

The peaceful life of the monastery lasted until 1653, when Patriarch Nikon, with the support of Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich, began a church reform that split Russian society into two irreconcilable camps. As early as June 8, 1658, a “black” (i.e., monastic) council was held at Solovetsky concerning the newly printed books sent from Moscow. The books were brought in, read, and examined; the monks saw “newly introduced rites” and blasphemy against the two-fingered sign of the cross by which the holy fathers Zosima and Savvatiy of Solovetsky, Sergius of Radonezh, and Kirill of Beloozero had crossed themselves.

“See, brethren,” said Archimandrite Iliya with tears in his eyes, “the last times have come: new teachers have arisen and turn us away from the Orthodox faith and from the tradition of the fathers; they order us to serve according to new service books on Latin crosses. Pray, brethren, that God may grant us to die in the Orthodox faith, as our fathers did, and that we accept no Latin service.”

After a careful study of the texts of the new books and comparison with ancient manuscripts (the Solovetsky Monastery possessed at that time the richest library of ancient manuscripts), the council decided: “We will not accept the new books, we will not serve according to them, and we will stand by our father the archimandrite…”

The new books were carried off to the “treasury chamber,” and the monks of Solovetsky Monastery continued to perform divine services according to the old books. At the same time, over the course of several years they sent the tsar five petitions in which they begged him for only one thing: to allow them to remain in the faith of their fathers.

“According to the tradition of the former Patriarch Nikon and his newly composed books, Nikon’s disciples now preach to us a new and unknown faith, a faith that neither we nor our great-grandfathers nor our fathers had ever heard of until this day,” while they “have reviled our Orthodox faith of the fathers, violated the entire church order and rule, and reprinted all the books according to their own understanding, contrary to God and corruptly.”

“We all weep with tears: have mercy on us, the poor and orphaned; command, Sovereign, that we remain in that same ancient faith in which thy father the sovereign and all the pious tsars and grand princes departed this life, and the venerable fathers of the Solovetsky monastery—Zosima, Savvatiy, German, and Metropolitan Filipp—and all the holy fathers pleased God.”

For the Solovetsky monks, as for all sincerely believing Russian people of the 17th century, betrayal of the old faith meant betrayal of Christ’s very Church and of God Himself. Therefore, like the first Christians, they were ready rather to go to torture, torment, and certain death than to retreat from the faith in which their ancestors had been saved. This thought was clearly expressed by the authors of the Troparion to the New Solovetsky Monastery Martyrs Who Suffered for Christ (composed at the end of the 17th century, Tone 4):

Ye despised the good things of earth And loved the Heavenly King Christ, the Son of God; Ye endured manifold wounds And with your blood sanctified anew the island of Solovetsky with a second consecration; And openly received crowns from God. Pray diligently for us, O blessed ones, Who celebrate your all-festive memory.

Meanwhile in Moscow, Nikon had abandoned the patriarchal throne (1658), and a timid hope appeared that the old faith might be restored. The persecution of zealots of ancient piety temporarily ceased; Archpriest Avvakum, Ioann Neronov, and others were recalled from exile, and at Solovetsky they continued to serve according to the old rite. For a time, it seemed that the Solovki and their stand for the faith had been forgotten…

However, hopes for the restoration of ancient Orthodoxy proved vain. On July 1, 1659, the Solovetsky hegumen Iliya reposed, and in March 1660 a new archimandrite was appointed in Moscow for the Solovetsky Monastery—the hieromonk Varfolomey—who, upon arriving at the monastery, removed the old councilors from the monastic council and introduced new ones pleasing to himself. The new archimandrite attempted to introduce new orders in the monastery as well. Thus in 1661 he tried to introduce the recently adopted “notational” (named) chanting in Moscow in place of the ancient “naonnoe” chanting. This provoked discontent among the brethren, and the leaders of the choirs continued to sing as before according to the old chant books. In 1663 Varfolomey made another attempt at reform, but it again ended in complete failure. The monastic brethren stood firmly for the old ways.

At that very time, the elder Gerasim Firsov wrote his “Epistle to a Brother” at Solovki, citing numerous testimonies in defense of the two-fingered sign of the cross, while the elder Feoktist composed a “Discourse on the Antichrist and His Secret Kingdom,” in which he proved the idea that the Antichrist already reigns spiritually in the world and that Nikon is his forerunner.

In 1666, Archimandrite Varfolomey went to the council in Moscow and openly went over to the side of the new-ritualists. There he informed the authorities about the stubbornness of the Solovetsky monks who refused to accept Nikon’s reform. In response, a special commission was dispatched, headed by Archimandrite Sergiy of the Savior-Yaroslavl Monastery, which arrived at Solovki on October 4, 1666.

Upon the commission’s arrival, a “black” council was convened at the monastery, at which the Solovetsky monks declared: “Formerly the entire Russian land was enlightened with every piety from the Solovetsky Monastery, and the Solovetsky Monastery was never under any reproach; it shone as a pillar and confirmation. But now you are learning a new faith from the Greeks, when the Greek teachers themselves do not even know how to cross their foreheads properly and walk about without crosses.” After long disputes and arguments about the faith, Archimandrite Sergiy returned to Moscow empty-handed.

A petition (the second one) was sent to the tsar after the archimandrite, which stated: “From Moscow there has been sent to thy tsarist house of prayer, to the Solovetsky Monastery, Archimandrite Sergiy of Yaroslavl’s Savior Monastery with companions to teach us church law according to the transmitted books… And we, thy pilgrims and servants, all with tears beg and entreat mercy of thee, the great sovereign: have mercy on us, most pious and most merciful great sovereign, Tsar and Grand Prince Aleksey Mikhaylovich, autocrat of all Great and Little and White Russia; send us, as the Heavenly Father sends, thy most generous and great mercy; command, sovereign, that this holy archimandrite Sergiy not violate the traditions of thy sovereign ancestors—the pious tsars and pious grand princes—and of our founders and great wonderworkers, the venerable and God-bearing fathers Zosima, Savvatiy, German, and the most holy Filipp, Metropolitan of Moscow and all Russia. And command, sovereign, that we remain in that same tradition in which our wonderworkers and the other holy fathers, and thy father the great sovereign, the most pious great sovereign Tsar and Grand Prince Mikhail Fyodorovich of all Russia, and thy grandfather the sovereign, the blessed Filaret Nikitich, Patriarch of Moscow and all Russia, passed their days in a life pleasing to God, so that we, thy pilgrims and laborers, not be scattered apart and thy great sovereign’s house of prayer, this frontier and border place, not fall into desolation for lack of people.”[2]

But the tsar had no time for the venerable Russian wonderworkers or for his “frontier house of prayer.” He was already dreaming of celebrating the liturgy in Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia and mentally trying on the Byzantine crown. The Solovetsky monks’ petition went unanswered. At the same time, the authorities did grant their request to remove the former Archimandrite Varfolomey. However, the new archimandrite appointed to the monastery was not Nikanor, whom the monastic brethren wanted to see in that position, but an entirely different man. On July 23, 1667, a patriarchal decree appointed the former Moscow builder Iosif, a like-minded associate of Varfolomey, as Solovetsky archimandrite. He was charged with introducing the new rites in the Solovetsky Monastery.

Upon learning of this, the Solovetsky monks sent council elders to meet the new archimandrite with a direct question: according to which books—old or new—would he serve in the monastery?

When the monks learned that Iosif was a supporter of the new rites, they did not approach him for his blessing. On September 15, 1667, a session of the black council was held in the monastery’s Cathedral of the Transfiguration, attended also by laypeople. Now, after the public anathematization of the old rites at the infamous Moscow council of 1666–1667 with the participation of the “ecumenical patriarchs,” it had become clear that the previous policy of simply ignoring the church reform would no longer work. A definite and direct decision had to be made. The Solovetsky black council categorically rejected the new books and rites and refused to recognize Iosif as their archimandrite.

Moreover, some other interesting facts came to light: the archimandrites Varfolomey (the former) and Iosif (the current one, rejected by the black council) had attempted to smuggle secretly into the monastery an entire boatload of wine to make the brethren drunk. “And when they arrived, we write to thee, great sovereign, without inventing anything: 39 barrels of mild, medium, and strong wine, plus about fifteen barrels of mead and beer. And in that, great sovereign, thy will be done: we, in accordance with the former monastic rule and the tradition of the wonderworkers, smashed all that drink in front of the monastery at the landing place.”[3]

On the day of the council, Iosif was handed a general petition concerning the faith, which stated the uselessness of sending further persuaders and the readiness of the Solovetsky monks to stand to the death: “Command, sovereign, that thy tsarist sword be sent against us, and that we be removed from this troubled life to that untroubled and eternal life; for we are not opposed to thee, great sovereign.”[4]

And something unheard-of occurred: in response to the humble entreaties of the Solovetsky monks, on May 3, 1668, by tsarist decree a military detachment was dispatched to the Solovki to bring the rebellious monastery to obedience. Thus began the monstrous eight-year siege—an act of sacrilege against the principal Orthodox shrine of the Russian North.

On June 22, 1668, the streltsy under the command of the court official Ignatiy Volokhov landed on Solovetsky Island. The monks locked themselves inside the monastery and, at one of the general assemblies, offered all wavering brethren as well as laypeople the opportunity to leave the monastery in advance. There turned out to be few such persons—about forty. The rest, numbering up to one and a half thousand, resolved to stand to the death for the old faith and “to receive the sweetness of future saints” rather than, having accepted the newly established traditions, to abide for a time in the sweetness of earthly life.

For four whole years Volokhov and his streltsy encamped beneath the monastery, in spring and summer “inflicting various torments,” firing upon it with cannon and muskets. In autumn they would withdraw to the shore, to Sumsky Ostrog, preventing anyone from leaving the monastery, ordering the seizure of service elders and servants and, after diverse tortures, putting them to death. Yet the local Pomor population actively aided the besieged monks, supplying the monastery with necessary foodstuffs and warning them of military preparations for the siege. Even the streltsy themselves, recruited chiefly from inhabitants of northern towns, participated reluctantly in the blockade of a holy place. Boats carrying salt, fish, and bread from the Sumsky Ostrog area to Arkhangelsk constantly “lost their way” and put in at the Solovetsky Islands.

In the summer of 1670 Volokhov sent “instructions under penalty” to all the Solovetsky saltworks, threatening death “without any mercy or pardon” for journeys to the monastery or letters sent there. But even this was of no avail. The Pomors did not cease supporting the besieged monastery. As a result, Volokhov, “having accomplished nothing,” was recalled to Moscow by tsarist decree.

In Volokhov’s place, in 1672, the centurion of Moscow streltsy Kliment Ievlev—a fierce and merciless man—was sent to destroy the Solovetsky monastery. To the previous 225 streltsy another 500 were added. In two years Ievlev inflicted upon the holy place “the most bitter straits” and “the most grievous want”: he burned all the cells around the monastery that had been built for the monks’ repose, the cattle yard together with the animals on Bolshaya Muksalma Island, and the fishing gear, attempting to starve the enclosed brethren out. But the cruel centurion received just retribution from God for his evil deeds: “stricken with the plague of putrefaction,” he was taken to Moscow in painful suffering.

In 1674 a new voevoda, Ivan Meshcherinov, “came beneath the cenoby” with thirteen hundred warriors “and many engines for battering walls.” At the same time, “unreliable” strelets commanders were replaced with “newly baptized foreigners” of the reitar formation (Major Kelin, Captain Bush, Lieutenants V. Gutkovsky and F. Stakhorsky). The tsar well understood that the hearts of these hired foreigners—who spoke Russian with difficulty and had accepted a foreign faith for mercenary reasons—would not flinch at the profanation of an Orthodox shrine. “The monastery he ungratefully desired to destroy and gathered an army… god-fighting and impious, of Germans and Poles.”[5]

Now that true professionals of the military art had arrived, the siege of the monastery was conducted according to all the rules of warfare of that era. Near the impregnable fortress walls they built small forts and redoubts, and the bombardment of the monastery became constant and targeted. At the same time, mines were dug beneath three of the monastery towers.

Yet despite the cruel siege, the Solovetsky monks continued the divine services. Despairing of human help and mercy, “with bitter tears and crying aloud” they besought aid and intercession from God, the most pure Sovereign Lady God-bearer, and the venerable Zosima and Savvatiy. By prayers and tears and “day-and-night standing before God they armed themselves against the warriors.” In the monastery two supplicatory services were sung each day so that the soldiers might not gain “boldness to enter within the monastery enclosure.”

And then a true miracle occurred: “the most merciful Lord, who is nigh unto all that call upon Him in truth, sent upon them a great pestilence manifested by signs of sores.” In three or four days about seven hundred men died. Terrified by this sign, many of the surviving streltsy took monastic vows and cleansed their souls by repentance. The invisible protection of the venerable fathers Zosima, Savvatiy, and German shielded the monastery from many assaults and cannon shots.

But voevoda Meshcherinov stopped at nothing. In mad blindness he ordered his henchmen to aim a cannon directly at the altar of the monastery’s cathedral church and fire. The cannonball flew through the window and struck the icon of the All-Merciful Savior that stood in the very altar. But even this seemed insufficient. Bombardment of the monastery began from three guns at once (160, 260, and 360 iron balls). After the first two shots the balls flew over the very crosses of the monastery churches and exploded in an empty place, while after the third one burst near the tomb of Venerable German. At that moment, in the church of the venerable Zosima and Savvatiy, the candle-lighter beheld “a venerable elder” approaching the holy shrines with the words: “Brethren Zosima and Savvatiy, arise; let us go to the righteous Judge Christ God to seek righteous judgment upon those who wrong us, who suffer us not to have rest even in the earth.” The venerable ones, rising in their reliquaries, answered: “Brother German, go and rest henceforth; vengeance upon those who wrong us is already being sent.” And lying down again, they reposed, and “the venerable elder who had come became invisible.”

The fathers of the Solovetsky monastery served thanksgiving molebens to the Lord and the venerable wonderworkers, and for a long time yet the monastery remained not only inaccessible to the soldiers, but “the firing of cannon and muskets” did it no harm, and none of the difficulties devised could shake the monks’ spirit in their resistance.

Convinced of the uselessness of artillery bombardment, Meshcherinov chose a different tactic. The streltsy dug trenches, made mines in which they placed gunpowder, and built towers and ladders the height of the monastery wall. Then a certain layman (that is, a secular person), the Solovetsky servant Dimitriy, cried out from the height of the monastery wall to the besiegers: “Why, O beloved ones, do ye labor so much and spill such great toil and sweat in vain and for naught, drawing near to the walls of the city? For even the sovereign tsar who sent you is being mown down by death’s scythe and is departing this light.” The besiegers paid no serious heed to these words, considering them empty foolishness. But the words proved prophetic.

In the winter of 1675–1676 Meshcherinov and the streltsy remained beneath the monastery walls, counting on quick success in a winter campaign. On December 23, 1675, he launched a “great assault.” Yet Meshcherinov’s hopes were dashed. Having lost Lieutenant Gutkovsky and more than a hundred streltsy, he was forced to retreat. The monastery seemed impregnable…

But, as the Old Believer historian Simeon Dionisievich writes, “it happens that a great house is ruined by its own household; it happens that mighty giants are slain by those closest to them; it happens that strong and unconquerable cities are betrayed by their own countrymen.” A traitor was found. A certain monk named Feoktist came by night to the enemy camp, having abandoned “his promise and the fathers’ monastery,” “abandoned ancient church piety, kissed Nikon’s new tradition,” and, like Judas, betrayed the enclosed brethren into the hands of the executioners, showing them a secret passage through the wall.

Although the traitor had come to Meshcherinov’s regiment as early as November 9, 1675, and promised to help take the monastery without difficulty, the soldiers dared not enter because the nights were light. Only in the night of January 22, 1676, did several dozen streltsy under the command of Major Stepan Kelin penetrate the monastery through the window beneath the drying-house by the White Tower that Feoktist had indicated. That night a fearful storm arose, bitter frost gripped the northern land, and the heavy falling snow blocked the guards’ vision.

To the Solovetsky centurion Login, who was sleeping in his cell, came a voice: “Login, arise; why sleepest thou? The host of the warriors is beneath the wall and will soon be in the city.” Awakening and seeing no one, Login crossed himself and fell asleep again. A second time the voice awoke him: “Login, arise; why sleepest thou so carelessly? Behold, the host of warriors is entering the city!” Rising, he checked the watch and, crossing himself again, slept. When for the third time he heard, “Login, arise; the host of warriors has already entered the city!” he roused the fathers of the monastery and told them of his threefold vision. The elders gathered in church to offer supplicatory singing to the Lord, the most holy God-bearer, and the venerable wonderworkers; then, having served matins and seeing no danger, they dispersed to their cells.

In the first hour of the night the traitor Feoktist and the soldiers who had gathered in the drying-room beneath the fortress wall broke the locks, opened the monastery gates, and let the rest of the army into the holy monastery. Hearing the noise, the valiant guards Stefan, Antoniy, and others—up to thirty guards and monks—came out to meet the invaders but were immediately slain. To the monks who had shut themselves in their cells it was promised that no harm would come to them; then the monastery fathers, “believing that fox,” came out to meet the “victors” bearing honorable crosses and holy icons. But the voevoda, forgetting the promise he had given, broke his oath and ordered the crosses and icons seized and the monks and laypeople separated into cells under guard.

Having entered the monastery, the streltsy began an inhuman slaughter of the monks. Meshcherinov personally interrogated the elders, asking one and the same question: “Why did ye resist the autocrat and drive back the army sent from the enclosure?” The first brought before him was the centurion Samuil, who boldly answered: “I resisted not the autocrat, but stood valiantly for the fathers’ piety and for the holy monastery, and those who wished to destroy the labors of the venerable fathers I did not allow within the enclosure.” Meshcherinov ordered the streltsy to beat Samuil until he gave up his soul to God. His body was thrown into a ditch.

Archimandrite Nikanor, who from old age and many years of prayerful labors could no longer walk unaided, was brought to interrogation on a small sledge. The aged archimandrite fearlessly answered his tormentor: “Because the newly introduced rules and innovations of Patriarch Nikon do not permit those living in the midst of the universe to keep God’s unchanging laws and the apostolic and patristic traditions, for this cause we withdrew from the world and settled on this sea-girt island as the possession of the venerable wonderworkers… You who have come to corrupt the ancient church rules, to mock the labors of the holy fathers, to destroy the divinely-saving customs—we righteously did not admit into the monastery.”

Showing no reverence for the monastic habit, the “venerable” gray hairs of the elder, or his great priestly rank, the voevoda began to heap upon Father Nikanor “dishonorable abuse and unseemly words.” But even this seemed too little. Meshcherinov personally beat the elder with a staff, knocked out his teeth, ordered him dragged by the feet outside the monastery enclosure, and thrown into a ditch on the bitter frost wearing only his undergarment. All night the sufferer struggled with wounds and cold, and at dawn “his spirit departed from the darkness of this present life into the never-fading everlasting light, and from the deepest ditch into the most exalted Heavenly Kingdom.”

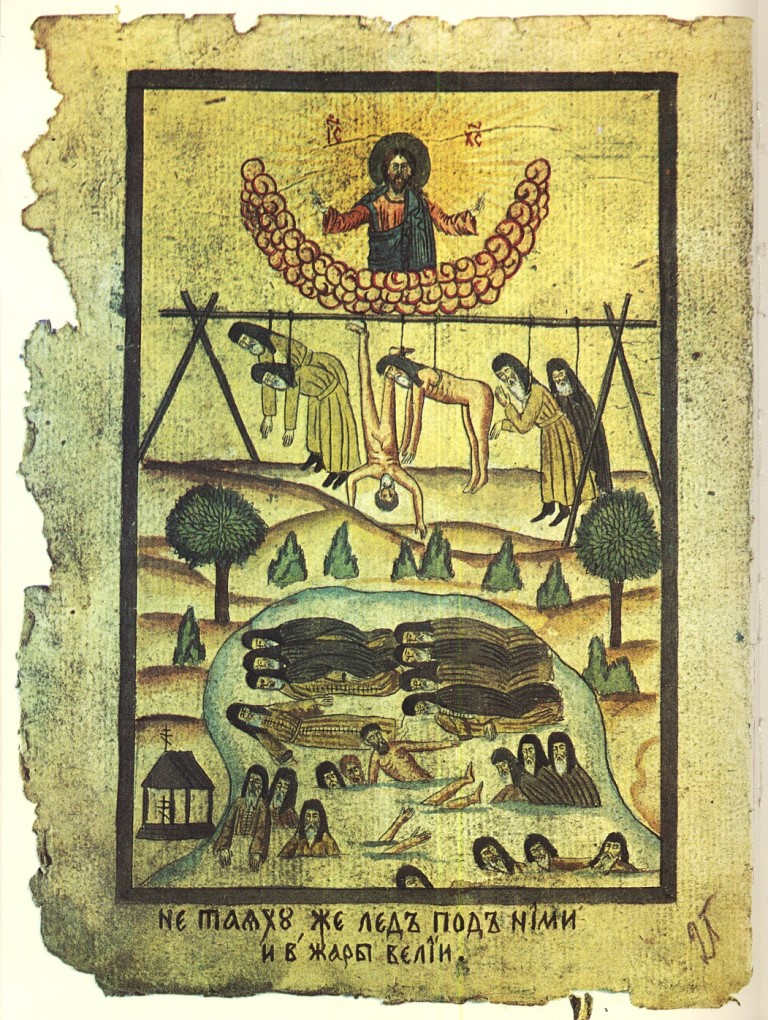

Next came the council elder Makariy, who boldly denounced the sacrilegious deeds of the streltsy. He too was beaten half to death by the merciless voevoda, dragged out by the feet amid mockery, and thrown onto the ice to freeze. To the skilled monastery craftsmen—the wood-carver Khrisanf and the icon-painter Feodor with his disciple Andrey—they cut off hands and feet and then beheaded them. Some monks and laypeople they hung by the neck or “between the ribs” on sharp hooks; others they tied to horses’ tails and dragged about the island “until they gave up the ghost.” No mercy was shown even to the sick and infirm—they were dragged by the feet to the seashore. There in the ice a huge hole was cut without water. There, bound two by two, 150 persons were placed and water slowly let in. Fierce frost stood without, and all the sufferers were frozen alive. Only a few, after first being beaten, were thrown into cellars or sent into exile.

The fury and cruelty of the tormentor knew no bounds. According to the list submitted by Meshcherinov to the new superior appointed from Moscow, only fourteen monks remained alive. In all, about five hundred monks and laypeople were tortured to death in the monastery! The earth and stones of the island were stained with the blood of the innocent Solovetsky sufferers. The whole western bay washing the monastery was choked with the bodies of those slain, frozen alive, and executed—monks and laypeople. In great numbers their corpses were piled near the monastery walls and dangled from gallows and trees. After the massacre, the bodies of the slain and those cut to pieces lay unburied for another half-year until a tsarist decree came ordering them committed to the earth.

But Meshcherinov did not stop even there. The executions and murders were accompanied by sacrilegious plundering of the monastery’s holy objects (a foretaste of the future “seizure of church valuables”). He “expropriated” not only the offerings and treasury accumulated over many centuries but the priceless monastery relics, including church vessels and icons. Only when the monastery had been completely laid waste did Meshcherinov send a courier to the tsar announcing “victory.”

Yet the tsar was not destined to learn of it: on the very next day after the taking of Solovetsky Monastery, January 23, 1676, he suddenly fell ill, and a week later, on January 29—on the eve of the day commemorating God’s Dread Judgment—he died. “And immediately after his death foul-smelling pus flowed from him through all the senses of the body; they stopped it with cotton wool, and scarcely were they able to bury him in the earth.”[6] The tsar’s early death was perceived throughout Russia as God’s punishment for the persecutions and apostasy from ancient Orthodoxy. Tradition tells of Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich’s late repentance: falling ill, he regarded his sickness as divine punishment and resolved to lift the siege of the monastery, sending his courier with news of pardon. And on the very day of the tsar’s death the two couriers met on the Vologda River: one bearing the joyful news of the monastery’s forgiveness, the other—of its destruction.

By God’s providence the sacrilegious destroyers of the Solovetsky monastery were also punished. The new tsar, Feodor Alekseyevich, having investigated the circumstances of the storming and the plundering of the monastery’s riches, ordered Meshcherinov punished for exceeding his authority and confined him on the same Solovki. The traitor Feoktist, sent after the capture as an administrative elder to Vologda, lost his mind, fell into fornication, then contracted an incurable disease and rotted alive.

After the investigation, the monks who had survived the “Solovetsky Resistance” were transported to the mainland. The holy fathers’ rules and traditions were changed to the new ones, and the brotherhood was replaced by supporters of the Nikonian reforms gathered from various monasteries. The spiritual level of these new inhabitants is attested by the complaints of Archimandrite Makariy to Patriarch Ioakim: life on the Solovki, compared with other monasteries, was “exceedingly poor”; the monks “grew weary,” refused to eat halibut, cod, and salmon, and in summer “wanted to flee the monastery” without even asking the superior’s leave.[7]

The violence and profanation of the holy place adversely affected the subsequent fate of the Solovki. The holy churches stood empty, the flow of pilgrims greatly diminished, and true ascetics of piety were no more. The former glory never again returned to Solovetsky Monastery, which became a prison for the confinement of dissidents.

[1] Fedotov G. P. The Saints of Ancient Russia. Moscow, 1990. P. 161–162.

[2] Denisov S. History of the Fathers and Sufferers of Solovki: Illuminated manuscript from the collection of F. F. Mazurin. Moscow, 2002. P. 227–228.

[3] Quoted from: Chumicheva O. V. The Solovetsky Uprising of 1667–1676. Novosibirsk, 1998. P. 47.

[4] Materials for the History of the Schism during the First Period of Its Existence. Ed. N. I. Subbotin. Vol. III. Moscow, 1878. P. 210.

[5] Bubnov N. Yu. An Unknown Petition of Ignatiy of Solovki to Tsar Feodor Alekseyevich // Manuscript Heritage of Ancient Russia. Leningrad, 1972. P. 102–103.

[6] Pustozersk Prose: A Collection. Moscow, 1989. P. 231. [7] Materials for the History of the Schism. Vol. III. P. 447–449.

[7] Materials for the History of the Schism. Vol. III. P. 447–449.